The Food Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pita Sandwiches Hummus Bowls Salads Grilled

HUMMUS BOWLS PITA SANDWICHES GRILLED ENTREES´ Choice of Original or Jaffa style hummus Made with original hummus, tomato, Includes one pita and your choice of two dips, Includes two white or wheat pitas cucumber, pickles & tahini on white, wheat, sides, or falafel. Cauliflower or Sweet Potato (gluten free pita + $1.55 each) or gluten free pita Fries as a side +$2.85 Add a handful of fries to any pita +$1.50 Classic $9.50 Chicken Skewer $19.95 Hummus with imported tahini, Yellow Garlic Falafel (v) $10.00 All-natural chicken thigh with secret olive oil, & our secret sauce (gf, v) spice blend (gf) Green Herb Falafel (v) $10.00 Beef Kebab $21.00 Falafel & Salad $11.95 Sabich $13.50 All-natural ground beef and lamb with Choice of yellow garlic falafel or blended herbs & garlic, drizzled with tahini (gf) green herb falafel with Israeli salad & Chicken Schnitzel $15.95 tahini dressing (gf, v) Breaded & fried chicken breast Vegetable Skewer $17.50 Onions, tomatoes, red bell peppers, Eggplant $12.95 Chicken Skewer $14.50 eggplant & mushrooms (gf, v) Chunky eggplant, stewed tomatoes With green cabbage & garlic (gf, v) + add an á la carte skewer: Beef Kebab $14.95 Chicken $10.00 Beef $11.50 Vegetable $8.00 Beets $12.95 With lamb, garlic & herbs Marinated beets, feta cheese, walnuts, orange zest, cilantro & balsamic reduction (gf) DIPS & SIDES Stewed Mushroom $11.95 Mushrooms & sautéed onions ISRAELI FAVORITES For dine in only – simmered in vegetable broth, Traditional Shakshuka $16.00 see Grab N Go for takeout with tahini (gf, v) (For dine in only) -

Cafe Jaffa Style (2)

48 Gloucester Street Boston, MA 02115 Hours: MONDAY-THURSDAY 11:00 A.M.- 10:30 P.M. FR\DAY-SATURDAY 11:00 A.M.-11:00 P.M. SUNDAY 12:00 P.M.- 10:00 P.M. Phone: 536-0230 We prepare all our items on the premises with only the freshest vegetables and choicest cuts of meat. Our ingredients are always wholesome and natural, and we never use additives or preservatives. No substitutions. No personal checks accepted. 15% service not included. All major credit cards accepted. Catering available. $10.00 credit card minimum requested. APPETIZERS Homemade traditional favorites served with pita bread. HOUMUS .................................................................................................................................................................. $4.95 A earthy blend ofground chick peas, specially seasoned. TAHINI ························································································································································$4.95 A savory dip of creamy pureed sesame seeds, garlic, lemon juice and spices. BABA GHANOUSB ................................................................................................................................................... $4.95 An exotic dish ofsmoked eggplant blended with sesame dressing, onions and spices. TABOULI .................................................................................................................................................................. $4.95 Fresh minced scallions, parsley and tomatoes combined with cracked -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

Chanukah Cooking with Chef Michael Solomonov of the World

Non-Profit Org. U.S. POSTAGE PAID Pittsfield, MA Berkshire Permit No. 19 JEWISHA publication of the Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, serving V the Berkshires and surrounding ICE NY, CT and VT Vol. 28, No. 9 Kislev/Tevet 5781 November 23 to December 31, 2020 jewishberkshires.org Chanukah Cooking with Chef The Gifts of Chanukah Michael Solomonov of the May being more in each other’s presence be among World-Famous Restaurant Zahav our holiday presents On Wednesday, December 2 at 8 p.m., join Michael Solomonov, execu- tive chef and co-owner of Zahav – 2019 James Beard Foundation award winner for Outstanding Restaurant – to learn to make Apple Shrub, Abe Fisher’s Potato Latkes, Roman Artichokes with Arugula and Olive Oil, Poached Salmon, and Sfenj with Cinnamon and Sugar. Register for this live virtual event at www.tinyurl.com/FedCooks. The event link, password, recipes, and ingredient list will be sent before the event. Chef Michael Solomonov was born in G’nai Yehuda, Israel, and raised in Pittsburgh. At the age of 18, he returned to Israel with no Hebrew language skills, taking the only job he could get – working in a bakery – and his culinary career was born. Chef Solomonov is a beloved cham- pion of Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape. Chef Michael Solomonov Along with Zahav in Philadelphia, Solomonov’s village of restaurants include Federal Donuts, Dizengoff, Abe Inside Fisher, and Goldie. In July of 2019, Solomonov brought BJV Voluntary Subscriptions at an another significant slice of Israeli food All-Time High! .............................................2 culture to Philadelphia with K’Far, an Distanced Holidays? Been There, Israeli bakery and café. -

SKYSCRAPER STYLE Per Adult Meal Purchase of $9.00 Or More

Visit us online at www.chompies.com! DELI RESTAURANT BAGEL FACTORY BAKERY CATERING ng Breakfast, Lunch & Dinner for Dine-In or Take-Out 7 D Award-Winni ays a Week! STOP BY OUR GOURMET BAKERY BEFORE YOU GO! PHOENIX Serving Our Guests the Ultimate in Paradise Valley Mall East Coast Tradition for 35 Years! (Between Sears and Dillard’s) NW Corner Cactus & Tatum • 602-710-2910 In 1979, the Borenstein Family...Lou & Lovey, Mark, Neal Mon.-Sat. 6 a.m.–9 p.m. • Sun. 6 a.m.–8 p.m. and Wendy of Queens, New York ventured west to Phoenix, SCOTTSDALE Arizona and ful lled their dream when they started their new Mercado Del Rancho business, Chompie’s Bagel Factory,DELI in a strip mall at 32nd 9301 East Shea Blvd. • 480-860-0475 Mon.-Sun. 6 a.m.–9 p.m. Street and Shea. With the supportRESTAURANT of our valued customers, locals and visitors alike, Chompie’sBAGEL has grown FACTORY to include TEMPE multiple New York Style Deli, Restaurant, Bagel & Bakery Rural & McClintock BAKERY locations throughout the Valley of the Sun. Still, each and 1160 East University • 480-557-0700 CATERING Mon.-Fri. 6 a.m.–9 p.m. • Sat.-Sun. 7 a.m.–9 p.m. Lou & Lovey Borenstein, N.Y.C. every customer is as important as our rst. We invite you to hear more of our story from Lou & Lovey on our YouTube channel. Thank you for stopping in CHANDLER for some good food, family and friends — Chandler Village Center 3481 W. Frye Rd • 480-398-3008 the good things in life! Mon.-Sat. -

IV: Construction

IV: Construction The Campaign Organization had raised a sufficient number of pledges. There remained, however, a great deal of work to be done before the Jewish hospital could open its doors, including the transformation of pledges into payments, the finding of suitable land, the construction and equipment of the hospital, and the hiring of an able and competent staff. Before those tasks could be undertaken, it was necessary to establish the post- campaign hospital leadership. Fortunately, much of this had been looked after by the end of the campaign. On August 9, 1929, Allan Bronfman, Michael Hirsch and Ernest G.F. Vaz had petitioned the provincial government for a charter so that the Jewish Hospital Campaign Committee could legally hold property. The government granted this charter, making the hospital committee a corporation, on September 5, 1929. On September 25, the legal formalities having been completed, the "Jewish Hospital Campaign Committee Inc." held its first official general meeting. Elections took place and resulted in the appointment of the following men as Directors: Allan Bronfman, Michael Hirsch, Ernest G.F. Vaz, Samuel Bronfman, Charles B. Fainer, Morris Ginsberg, Robert Hirsch, Abraham H. Jassby, David Kirsch, Joseph Levinson Sr., Michael Morris, Harry Reubins, Hyman M. Ripstein, Alderman Joseph Schubert, Isaac Silverstone, Louis Solomon, Abraham Moses Vineberg and Dr. Max Wiseman. The Directors held their first meeting on October 7 and then chose Allan Bronfman as President of the Board. Other officers appointed included: Michael Hirsch (Chairman of the Board of Directors), Samuel Bronfman (Vice-President), Joseph Levinson Sr. (Treasurer), Robert Hirsch (Secretary) and Ernest Vaz (Executive Secretary). -

Fifty Third Year the Jewish Publication Society Of

REPORT OF THE FIFTY THIRD YEAR OF THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1940 THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA OFFICERS PRESIDENT J. SOLIS-COHEN, Jr., Philadelphia VICE-PRESIDENT HON. HORACE STERN, Philadelphia TREASURER HOWARD A. WOLF, Philadelphia SECRETARY-EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MAURICE JACOBS, Philadelphia EDITOR DR. SOLOMON GRAYZEL, Philadelphia HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS ISAAC W. BERNHEIM3 Denver SAMUEL BRONFMAN* Montreal REV. DR. HENRY COHEN1 Galveston HON. ABRAM I. ELKUS3 New York City Louis E. KIRSTEIN1 Boston HON. JULIAN W. MACK1 New York City JAMES MARSHALL2 New York City HENRY MONSKY2 Omaha HON. MURRAY SEASONGOOD3 Cincinnati HON. M. C. SLOSS3 San Francisco HENRIETTA SZOLD2 Jerusalem TRUSTEES MARCUS AARON3 Pittsburgh PHILIP AMRAM3 Philadelphia EDWARD BAKER" Cleveland FRED M. BUTZEL2 Detroit J. SOLIS-COHEN, JR.3 Philadelphia BERNARD L. FRANKEL2 Philadelphia LIONEL FRIEDMANN3 Philadelphia REV. DR. SOLOMON GOLDMAN3 Chicago REV. DR. NATHAN KRASS1 New York City SAMUEL C. LAMPORT1 New York City HON. LOUIS E. LEVINTHALJ Philadelphia HOWARD S. LEVY1 Philadelphia WILLIAM S. LOUCHHEIM3 Philadelphia 1 Term expires in 1941. 2 Term expires in 1942. 3 Term expires in 1943. 765 766 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK REV. DR. LOUIS L. MANN' Chicago SIMON MILLER2 Philadelphia EDWARD A. NORMAN3 New York City CARL H. PFORZHEIMER1 New York City DR. A. S. W. ROSENBACH1 Philadelphia FRANK J. RUBENSTEIN2 Baltimore HARRY SCHERMAN1 New York City REV. DR. ABBA HILLEL SILVERJ Cleveland HON. HORACE STERN2 Philadelphia EDWIN WOLF, 2ND* Philadelphia HOWARD A. WOLF* Philadelphia PUBLICATION COMMITTEE HON. LOUIS E. LEVINTHAL, Chairman Philadelphia REV. DR. BERNARD J. BAMBERGER Albany REV. DR. MORTIMER J. COHEN Philadelphia J. SOLIS-COHEN, JR Philadelphia DR. -

5 Convenient Locations

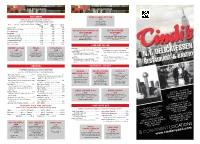

EGG VARIETY CINDI’S COMBO PLATTER Served with a Choice of Grits, Hash Browns or Home Fries and 13.95 a Choice of Toast, Buttermilk Pancakes, Biscuits and Gravy, or Bagel. One Stuffed Cabbage, Cottage Cheese or sliced Tomatoes may be substituted for Hash Browns. One Potato Pancake, Cheese . .add .95 Egg substitutes available: Egg Whites . .add .95 Egg Beaters . .add .95 and One Meat Knish 3 EGGS 2 EGGS 1 EGG Eggs (Any Style) . 7.75 . 7.25. 6.75 Link or Patty Sausages & Eggs . 9.00 . 8.50. 8.00 Bacon Strips & Eggs . 9.00 . 8.50. 8.00 OPEN FACED CORNED BEEF HOT ROAST BEEF Ham & Eggs . 9.25 . 8.75. 8.25 OR PASTRAMI OR TURKEY Canadian Bacon & Eggs . 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 13.95 12.95 Ground Beef Patty & Eggs . 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 Served over Grilled Potato Knish, Potato Salad Served Open Faced on White Bread with Gravy. or Cole Slaw w/Gravy Chicken Fried Steak & Eggs . 10.00 . 9.50. 9.00 Served with French Fries or Potato Salad With Meat Knish 14.95 and Cole Slaw Corned Beef Hash & Eggs. 10.25 . 9.70. 9.20 Pork Chops & Eggs . 11.50 . 11.00. 10.50 Ribeye Steak & Eggs. 16.00 . 15.50. 15.00 SOME LIKE IT COLD CHORIZO & EGGS MIGAS LOX & EGGS Fruit Platter . 9.95 Egg Salad . 8.95 9.50 9.50 12.95 Assorted Seasonal Fruit "You'll love this one" Served with Lettuce, Tomatoes, Cole Slaw and Mexican Sausage mixed 2 Eggs, Jalapenos, Onions, 3 Scrambled Eggs, Lox, Onions Chicken Salad . -

Catering and Delivery

CATERING No need to worry! We have you covered! Stalactites can be delivered straight AND to your office, workplace or home, DELIVERY hot, fresh and on time! Each Stalactites order is freshly sliced and prepared in our store just before we deliver to you! We only use premium quality, A-grade meat and ingredients and all of our dips and sweets are homemade using our 40 year old recipe. We are the only Greek restaurant in all of Australia that has been given Coeliac Australia Accreditation, making our Gluten free choices 100% safe for people suffering from Coeliac disease. We can also accommodate vegan, vegetarian and other dietary requirements. Each tray serves 10-15 people. LARGE DIPS - SERVES 10 - 15 OPTION 1 : $13 each LAMB GIROS CATERING TRAY $100 Homemade Tzatziki SHARING Yoghurt, garlic and cucumber (V) (GF) MENU CHICKEN GIROS CATERING TRAY Homemade Hommus $100 Chickpea, sesame and lemon (V) (GF) MIXED GIROS CATERING TRAY Homemade Eggplant $100 Eggplant and garlic dip (V) GREEK SALAD CATERING TRAY Homemade Tarama $39 Caviar and lemon dip HOT SEASONED CHIPS CATERING TRAY ADD: $29 Pita Bread $2.50 each BAKLAVA PACK - SERVES 1–3 Gluten Free/Vegan Pita Bread $4.50 each 3 pieces in a pack $5 each RICE PUDDING - SERVES 1 Homemade rice custard dusted with cinnamon (GF) $5 each All souvlakis come with lettuce, OPTION 2: tomato, onion, and Tzatziki INDIVIDUAL LAMB GIROS SOUVLAKI Tender marinated lamb giros SOUVLAKIS from the spit in pita $17.50 CHICKEN GIROS SOUVLAKI Tender marinated chicken giros from the spit in pita $17 MIXED GIROS SOUVLAKI -

1. Agudas Shomrei Hadas Rabbi Kalman Ochs 320 Tweedsmuir Ave

1. Agudas Shomrei Hadas Rabbi Kalman Ochs 320 Tweedsmuir Ave Suite 207 Toronto, Ontario M5P 2Y3 Canada (416)357-7976 [email protected] 2. Atlanta Kashrus – Peach Kosher 1855 LaVista Road N.E. Atlanta, GA 30329 404-634-4063 www.kosheratlanta.org Rabbi Reuven Stein [email protected] 404-271-2904 3. Beth Din of Johannesburg Rabbi Dovi Goldstein POB 46559, Orange Grove 2119 Johannesburg, South Africa 010-214-2600 [email protected] 4. BIR Badatz Igud Rabbonim 5 Castlefield Avenue Salford, Manchester, M7 4GQ, United Kingdom +44-161-720-8598 www.badatz.org Rabbi Danny Moore 44-161-720-8598 fax 44-161-740-7402 [email protected] 5. Blue Ribbon Kosher Rabbi Sholem Fishbane 2701 W. Howard Chicago, IL 60645 773-465-3900 [email protected] crckosher.org 6. British Colombia -BC Kosher - Kosher Check Rabbi Avraham Feigelstock 401 - 1037 W. Broadway Vancouver, B.C. V6H 1E3 CANADA 604-731-1803 fax 604-731-1804 [email protected] 7. Buffalo Va’ad Rabbi Eliezer Marcus 49 Barberry Lane Buffalo, NY 11421 [email protected] 716-534-0230 8. Caribbean Kosher Rabbi Mendel Zarchi 18 Calle Rosa Carolina, PR 00979 787.253.0894 [email protected] 9. Central California Kosher Rabbi Levy Zirkind 1227 E. Shepherd Ave. Fresno, CA 93720 559-288-3048 [email protected] centralcaliforniakosher.org 10. Chanowitz, Rabbi Ben Zion 15 North St. Monticello, NY 12701 [email protected] 845-321-4890 11. Chelkas Hakashrus of Zichron Yaakov 131 Iris Road Lakewood, NJ 08701 732 901-6508 Rabbi Yosef Abicasis [email protected] 12. -

Traveling with Jewish Taste Baking — and Breaking Bread with Wheat by Carol Goodman Kaufman

Page 12 Berkshire Jewish Voice • jewishberkshires.org June 15 to July 26, 2020 BERKSHIRE JEWISH VOICES Traveling with Jewish Taste Baking — and Breaking Bread With Wheat By Carol Goodman Kaufman “Listen to this dream I had: We were binding pandemic quarantine has us Zooming and Skyping and FaceTiming our meals sheaves of grain out in the field when suddenly with family and friends. my sheaf rose and stood upright, while your In Jewish tradition, the word “kemach,” flour, is used to denote food. Pirkei sheaves gathered around mine and bowed Avot, the Sayings of the Fathers, goes so far as to state, “Im ayn kemach ayn down to it.” (Genesis 37:6-7) Torah; im ayn Torah ayn kemach,” translated as, “If there is no food, then there is While wheat may seem to be a rather no Torah; and if there is no Torah, no food.” The rabbis meant that if there is no boring food to write about — it’s not sweet and sustenance to support our physical being, then it is impossible for us to absorb luscious like the date, or the words of Torah. Conversely, if we have “in” like the pomegranate no spirituality from Torah in our lives, then — it is such an important our souls are starved. Research about chil- part of our ancestors’ dren’s learning correlated with having a good diet that it’s mentioned breakfast seems to support the adage. at least 39 times in the What makes wheat flour unique is that Tanach. And our guy it contains gluten, the protein that enables Joseph certainly spent a lot of time thinking about it, both a dough to rise by forming carbon dioxide in interpreting his own dreams and those of the Pharaoh for during fermentation, thus producing light whom he worked. -

EN-Combined-Menu.Pdf

ARTHURS T 514.757.5190 [email protected] ARTHURS NOSH BAR @ARTHURSMTL TAKEOUT MENU ALL OF OUR FISH IS PART OF THE SUSTAINABLE MOVEMENT, Salads FISH ASC CERTIFIED SANDWICHES ADD 1 SCOOP OF TUNA SALAD, EGGPLANT SALAD OR SALMON TOWER FOR 2 $30.00 MC ARTHUR $15.00 GRILLED CHICKEN $4.50 BREAKFAST HOUSE SMOKED SALMON OR GRAVLAX, CHICKEN SCHNITZEL, ICEBERG SLAW, MAYO, PICKLES, WHIPPED CREAM CHEESE, SESAME BAGELS WITH SERVED ON CHALLAH BREAKFAST SANDWICH $10.50 EGGS AND SALAMI $12.50 #KGMTL’S POST APOCALYPSE $18.00 ALL THE FIXINS’ SCRAMBLED EGGS, SALAMI, AMERICAN SCRAMBLED EGGS, LATKE, ROMAINE, KALE, SHREDDED CARROTS, THE CAPUTO SPECIAL $16.00 CHEESE, LETTUCE, MAYO, SERVED ON A SALAMI, PRESSED CHALLAH ROLL SHREDDED BEETS, CUCUMBER, PICKLED ROAST BEEF, SPICY GIARDINIERA, SWEET PEPPERS, CHALLAH ROLL ADD CHEESE $1.00 TURNIPS, HOT PEPPERS, CHERRY TOMATOES, GREEN CHILI CHEESE, AU JUS, SERVED ON A ROLL RADISH, PARSLEY, MINT, BAGEL CHIPS, NOSHES THE CLASSIC $15.00 LATKE SMORGASBORD $15.50 ZAATAR,HUMMUS, SUMAC DRESSING LATKES $8.00 SCRAMBLED EGGS, LATKE, RAE RAY’S $15.00 BAGEL, HOUSE SMOKED SALMON, SERVED WITH HOUSE APPLE SAUCE, CREAM CHEESE, PICKLED ONIONS, SALMON GRAVLAX, ISRAELI SALAD, GRILLED CHICKEN, AVOCADO, TOMATO, COLESLAW, QUINOA BOWL $18.00 HORSERADISH, SOUR CREAM SLICED TOMATOES, CAPERS, DILL PRESSED CHALLAH ROLL LETTUCE, MAYO AND MUSTARD ROMAINE, KALE, MARINATED BEETS, ADD BEEF BACON $3.75 SHREDDED CARROTS, QUINOA, AVOCADO, PEROGIES $15.00 SYRNIKI $15.00 THE SCRAMBLE $15.00 ADD HOUSE HOT PEPPERS $1.00 COLESLAW, ROASTED SWEET POTATOES, POTATO