The Story of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Darebin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Melbourne-Dreaming-Intro 1.Pdf (Pdf, 1.91

ABOUT THIS BOOK Melbourne Dreaming is both a guide book and social history of Melbourne, and the events and cultural traditions that have shaped local Aboriginal people’s lives. It aims to show where to look to gain a better understanding of the rich heritage and complex culture of Aboriginal people in Melbourne both before and since colonisation. It was first published in 1997. This is a completely updated and expanded edition. Melbourne Dreaming provides practical information on visiting both historical and contemporary sites located in the city centre, surrounding suburbs and outer areas. Arranged into seven precincts, Melbourne Dreaming takes you to beaches, parklands, camping places, historical sites, exhibitions, cultural displays and buildings. For Melbourne’s Aboriginal people the landscape prior to European settlement over which we travel was the face of the divine — the imprint of the ancestral creation beings that shaped the landscape on their epic journeys. Exploring Melbourne’s Aboriginal places is a way of paying respect to this sacred tradition while learning more about our shared and ancient history. Sites include locations and traces of important places before European settlement in 1835 such as shell middens, scarred trees, wells, fish traps, mounds and quarries. Other sites describe critical events that occurred because of the impact of European settlement. More recent places are the focus of contemporary life. What these places share in common is that each illustrates an important part of the overall story of the first inhabitants, the Kulin. Stories and photographs of some places of interest which have restricted access or cannot be visited have also been included. -

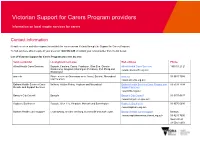

Victorian Support for Carers Program Providers

Victorian Support for Carers Program providers Information on local respite services for carers Contact information Respite services and other support is available for carers across Victoria through the Support for Carers Program. To find out more about respite in your area call 1800 514 845 or contact your local provider from the list below. List of Victorian Support for Carers Program providers by area Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Alfred Health Carer Services Bayside, Cardinia, Casey, Frankston, Glen Eira, Greater Alfred Health Carer Services 1800 51 21 21 Dandenong, Kingston, Mornington Peninsula, Port Phillip and <www.carersouth.org.au> Stonnington annecto Phone service in Grampians area: Ararat, Ballarat, Moorabool annecto 03 9687 7066 and Horsham <www.annecto.org.au> Ballarat Health Services Carer Ballarat, Golden Plains, Hepburn and Moorabool Ballarat Health Services Carer Respite and 03 5333 7104 Respite and Support Services Support Services <www.bhs.org.au> Banyule City Council Banyule Banyule City Council 03 9457-9837 <www.banyule.vic.gov.au> Baptcare Southaven Bayside, Glen Eira, Kingston, Monash and Stonnington Baptcare Southaven 03 9576 6600 <www.baptcare.org.au> Barwon Health Carer Support Colac-Otway, Greater Geelong, Queenscliff and Surf Coast Barwon Health Carer Support Barwon: <www.respitebarwonsouthwest.org.au> 03 4215 7600 South West: 03 5564 6054 Service provider Local government area Web address Phone Bass Coast Shire Council Bass Coast Bass Coast Shire Council 1300 226 278 <www.basscoast.vic.gov.au> -

City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile

Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 Early Childhood Community Profile City of Darebin Aboriginal Community 2009 This Aboriginal Early childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio CdiiCoordination, ini the h ViVictorian i Government G DDepartment of f EdEducation i and d EEarly l ChildhChildhood d DDevelopment. l The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and developmental outcomes of young Aboriginal children. They are published to aid Aboriginal organisations and local councils, as well as Best Start partnerships, with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve these outcomes. The Department of Human Services, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Aboriginal Early Childhood Community Profile i Published by the Victorian Government DepartmentDepartment of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. January 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisionsprovisions of the Copyright Act 19681968.. Principal author and analyst: Hiba -

Traditional Language Used in Production

Traditional Language Used in Production 75 Traditional Language Used in Production There were several dialects spoken within the Border Rivers and Gwydir catchments. They included the Gamilaraay, Yuwalaraay and Yuwalayaay dialects as spoken by members of the Kamilaroi (Gomeroi) nation. The Nganyaywana language was spoken by members of the Anaiwan (or Eneewin) nation, whose land extends south from the border with the Banbai nation (near Guyra) towards Uralla and westward towards Tingha. Other notable languages within the area included Yukumbal (Jukumbal), from the Bundarra/Tingha/Inverell area, and Ngarabal, which was spoken around the Glen Innes area. This book uses and provides information on a few of the dialects spoken within the catchment. It is not intended for this book to be a language reference book, but the use of language names is included to help keep our language alive and for educational purposes. In some cases Aboriginal words have not been included as it has not been possible to collect detailed information on the relevant dialects. This book uses words and references primarily relating to the Gamilaraay, Yuwalaraay, Yuwalayaay, Banbai and Nganyaywana dialects (White 2010 pers. comm.). English Word Traditional Language / Dialect / Explanation Aboriginal nation anaiwan (Uralla/Bundarra / Armidale) district axe (handle) birra (Yuwaalayaay) axe (stone) birran.gaa (Yuwaalaraay) gambu (Yuwaalaraay) (Yuwaalayaay) tila (Nganyaywana-Anaiwan) yuundu (Gamilaraay) (Yuwaalaraay) (Yuwaalayaay) Aboriginal nation of the Guyra region banbai -

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 JULY 2019 2 Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Table of contents Introduction 4 Teacher background information 24 for Years 7 to 10 Background 5 Year 7 teacher background information 26 Process for developing the elaborations 6 Year 8 teacher background information 86 How the elaborations strengthen 7 the Australian Curriculum: Science Year 9 teacher background information 121 The Australian Curriculum: Science 9 Year 10 teacher background information 166 content elaborations linked to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Foundation 10 Year 1 11 Year 2 12 Year 3 13 Year 4 14 Year 5 15 Year 6 16 Year 7 17 Year 8 19 Year 9 20 Year 10 22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority 3 Introduction This document showcases the 95 new content elaborations for the Australian Curriculum: Science (Foundation to Year 10) that address the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority. It also provides the accompanying teacher background information for each of the elaborations from Years 7 -10 to support secondary teachers in planning and teaching the science curriculum. The Australian Curriculum has a three-dimensional structure encompassing disciplinary knowledge, skills and understandings; general capabilities; and cross-curriculum priorities. It is designed to meet the needs of students by delivering a relevant, contemporary and engaging curriculum that builds on the educational goals of the Melbourne Declaration. -

Engaging Indigenous Communities

Engaging Indigenous Communities REGIONAL INDIGENOUS FACILITATOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S GOALS AND The Port Phillip & Westernport CMA employs a Regional ASPIRATIONS Indigenous Facilitator funded through the Australian During 2014/15, a study was undertaken with Government’s National Landcare Programme. In Wurundjeri, Wathaurung, Wathaurong and Boon 2014/15, the facilitator arranged numerous events Wurrung people regarding their communities’ goals and and activities to improve the Indigenous cultural aspirations for involvement in land management and awareness and understanding of Board members and sustainable agriculture. The study improved the mutual staff from the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and from understanding of priority activities for the future and various other organisations and community groups. set a basis for potential formal agreements between The facilitator also worked directly with Indigenous the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and the Indigenous organisations and communities to document their goals organisations. relating to natural resource management and agriculture. A coordinated program of grants was established to help INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT GRANTS Indigenous organisations undertake on-ground projects and training to increase employment opportunities. In 2014/15, $75,000 of Indigenous environment grants were awarded as part of the Port Phillip & Westernport IMPROVING CULTURAL AWARENESS AND CMA’s project. This included grants to: UNDERSTANDING • Wathaurung Aboriginal Corporation to run 4 community, business and corporate -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Of the Tasmanian Aborigines

7. NOTES ON THE HUNTING STICKS (LUGHKANA), SPEARS (PERENNA), AND BASKETS (TUGH- BRAN A) OF THE TASMANIAN ABORIGINES. PL IX., X., XL. XII., XIII., XIV.. XV. By Fritz Noetling, M-A., Ph.D., Etc. (Read July 10th. 1911.) INTRODUCTION. In the pajJcrs previously published in the Society's journal I have conclusively proved, and it can now be con- si.Iered as an established fact, that the stone relics of the Aborigines represent implements only, and not weapons. This is a fact of the greatest importance, and its signifi- cance will only be fully realised when we apply it to the study of archaeolithic man in Europe- The Tasmanian Aborigines had made at least one great invention, viz.. they had discovered that a certain kind of rock yielded sharp- edged flakes when broken. (1). They also found that these sharp-edged flakes could be used for most of the re- quirements of their simple life. But here again we come upon one of those curious psychological pi'oblems that are so difiicult to explain. The Aborigines had undoubtedly discovered that these flakes were excellent cutting imple- ments, as thev have generally a fine edge, and often enough terminated in a sharp ])oint To us it seems easy enough to turn the good qualitie.s of the sharp flakes to other uses than merely as tools. The instinct of self-presei-A'ation is paramount in all hviman beings, and. as has often been stated, it is the mother of all those inventions that have changed the life of our prehistoric ancestors into that of modem mankind. -

7.5. Final Outcomes of 2020 General Valuation

Council Meeting Agenda 24/08/2020 7.5 Final outcomes of 2020 General Valuation Abstract This report provides detailed information in relation to the 2020 general valuation of all rateable property and recommends a Council resolution to receive the 1 January 2020 General Valuation in accordance with section 7AF of the Valuation of Land Act 1960. The overall movement in property valuations is as follows: Site Value Capital Improved Net Annual Value Value 2019 Valuations $82,606,592,900 $112,931,834,000 $5,713,810,200 2020 Valuations $86,992,773,300 $116,769,664,000 $5,904,236,100 Change $4,386,180,400 $3,837,830,000 $190,425,800 % Difference 5.31% 3.40% 3.33% The level of value date is 1 January 2020 and the new valuation came into effect from 1 July 2020 and is being used for apportioning rates for the 2020/21 financial year. The general valuation impacts the distribution of rating liability across the municipality. It does not provide Council with any additional revenue. The distribution of rates is affected each general valuation by the movement in the various property classes. The important point from an equity consideration is that all properties must be valued at a common date (i.e. 1 January 2020), so that all are affected by the same market. Large shifts in an individual property’s rate liability only occurs when there are large movements either in the value of a property category (e.g. residential, office, shops, industrial) or the value of certain locations, which are outside the general movements in value across all categories or locations. -

Guide to Backyard Biodiversity

Backyard Biodiversity A guide to creating wildlife-friendly and sustainable gardens in Boroondara ‘We must feel part of the land we walk on and love the Backyard plants that grow there ... if we are to achieve a spirit Biodiversity in the garden.’ Gordon Ford (1999), The natural Australian garden. Bloomings Contents Books We love our gardens and trees 1 Creating a wildlife-friendly garden supports biodiversity 2 Why biodiversity matters 3 Adopt sustainable gardening principles 5 Your Council is working to protect and enhance the local environment 6 Building on what we have — biodiversity corridors 8 Backyard biodiversity — let’s get started 12 Attracting native birds to your garden 14 Your garden honeyeaters 16 A garden full of parrots 18 A chorus of garden birds 22 Butterflies, dragonflies and other garden insects 25 Inviting frogs to your garden 28 Letting lizards lounge in your garden 30 The secret lives of our native mammals 32 We encourage you to get involved 35 ‘The City of Boroondara recognises its responsibility as a custodian of the environment, as well as respectfully acknowledging the Wurundjeri people as the first owners of this country, and the custodians of the cultural heritage of the lands.’ Biodiversity Strategy, City of Boroondara Cover images Feature image: One of many inspiring Boroondara gardens featured in this booklet. Bottom left to right: Silvereye, Yellow-banded Dart, Gang-gang Cockatoo and Native Fuchsia (Correa reflexa). We love our gardens and trees Residents of Boroondara are justifiably proud of our green leafy suburbs and wonderful You can become parks and gardens. The name a wildlife gardener Boroondara signifies shady place in the local indigenous Many Boroondara gardeners have already started to create magical dialect. -

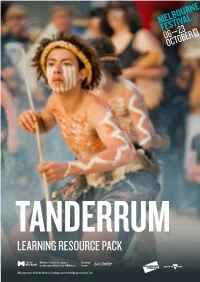

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective.