Of Piano Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Pharoah Sanders Tauhid Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pharoah Sanders Tauhid mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Tauhid Country: US Style: Free Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1857 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1425 mb WMA version RAR size: 1420 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 437 Other Formats: AHX AC3 WMA MMF RA APE VOC Tracklist Hide Credits Upper Egypt & Lower Egypt A 17:00 Written-By – Pharoah Sanders Japan B1 3:29 Written-By – Pharoah Sanders Aum / Venus / Capricorn Rising B2 14:52 Written-By – Pharoah Sanders Companies, etc. Made By – ABC Records, Inc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Published By – Pamco Music Published By – PAB Music Corp. Credits Bass – Henry Grimes Design [Cover] – Robert Flynn Design [Liner] – Joe Lebow Drums – Roger Blank Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Guitar – Warren "Sonny" Sharrock* Liner Notes – Nat Hentoff Percussion – Nat Bettis Photography By – Charles Stewart* Piano – Dave Burrell Producer – Bob Thiele Tenor Saxophone, Alto Saxophone, Piccolo Flute, Vocals – Pharoah Sanders Notes rec Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Van Gelder Recording Studio 11/15/66 Most probably a 70ies release. Green/plum ABC/Impulse! label. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Side A): AS-9138-A 1 B T Matrix / Runout (Runout Side B): AS-9138-B 2 B T Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Pharoah Tauhid (LP, Album, AS-9138 Impulse! AS-9138 US 1967 Sanders Gat) Pharoah Tauhid (CD, Album, GRD-129 GRP, Impulse! GRD-129 US Unknown Sanders RE, RM) Pharoah Tauhid (CD, Album, GRP 11292 GRP, Impulse! -

Pharoah Sanders, Straight-Ahead and Avant-Garde

Jazz Perspectives ISSN: 1749-4060 (Print) 1749-4079 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjaz20 Pharoah Sanders, Straight-Ahead and Avant-Garde Benjamin Bierman To cite this article: Benjamin Bierman (2015) Pharoah Sanders, Straight-Ahead and Avant- Garde, Jazz Perspectives, 9:1, 65-93, DOI: 10.1080/17494060.2015.1132517 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2015.1132517 Published online: 28 Jan 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjaz20 Download by: [Benjamin Bierman] Date: 29 January 2016, At: 09:13 Jazz Perspectives, 2015 Vol. 9, No. 1, 65–93, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2015.1132517 Pharoah Sanders, Straight-Ahead and Avant-Garde Benjamin Bierman Introduction Throughout the early 1980s, Sweet Basil, a popular jazz club in New York City, was regularly packed and infused with energy as the Pharoah Sanders Quartet was slam- ming it—Sanders on tenor, John Hicks on piano, Walter Booker on bass, and Idris Muhammad on drums.1 The music was up-tempo and unflagging in its intensity and drive. The rhythm section was playing with a straight-ahead yet contemporary feel, while Sanders was seamlessly blending the avant-garde or free aesthetic and main- stream straight-ahead jazz, as well as the blues and R&B influences from early in his career.2 This band—and this period of Sanders’s career—have been largely neglected and Sanders himself has generally been poorly represented in the media.3 Sanders, as is true for many, many musicians, suffers from the fact that in critical discourses jazz styles often remain conceptualized as fitting into pre-conceived cat- egories such as straight-ahead, mainstream, and avant-garde or free jazz. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

P 100 Albums 101 to 14

Basic Album Inventory A check list of best selling pop albums other than those appearing on the CASH BOX Top 100 Album chart. Feature is designed to call wholesalers' & retailers' attention to key catalog, top steady selling LP's, as well as recent chart hits still going strong in sales. Information is supplied by manufacturers. This is a weekly revolving list presented in alphabetical order. It is advised that this card be kept until the list returns to this alphabetical section. HOB Chet Atkins Play Guitar w/Chet Atkins VI 17506 Ventures Play Guitar w/Ventures VII 17507 Thompson Community Ventures The Horse 8057 Singers of Chicago Rise Up & Walk HOB 277 Ventures Underground Fire 8059 Shirley Caesar My Testimony HOB 278 ($5.98 Sugg. Institutional Choir List) More Golden Greats 8060 Of The Church Of Hawaii Five -O 8061 God In Christ Stretch Out HOB 279 Swamp Rock 8062 The Swan Silvertones Only Believe HOB 282 Shirley Caesar Jordan River HOB 283 IMPULSE Five Blind Boys Brown Chicken Fat AS 9152 Tell Mel Of Alabama Jeses HOB 284 Mel Brown The Wizard AS 9169 The Stars Of Faith We Shall Be Changed HOB 285 I'd Rather Suck My Thumb AS 9186 Albertina Walker & Mel Brown Ray Charles Genius + Soul = Jazz AS 2 The Caravans Jesus Will Fix It HOB 287 Brockington Ensemble Alice Coltrane A Monastric Trio AS 9156 Up Above My Head HOB 289 Alice Coltrane featuring Swan Silvertones Great Camp Meeting HOB 290 Pharoah Sanders Ptah The El Daoud AS 9196 Various Artists Gospels Greats Vol. -

Prophetics and Aesthetics of Muslim Jazz Musicians in 20Th Century America Parker Mcqueeney Committee: Marty Ehrlich and Carl Clements

1 S ultans of Swing: Prophetics and Aesthetics of Muslim Jazz Musicians in 20th Century America Parker McQueeney Committee: Marty Ehrlich and Carl Clements 2 3 Table of Contents Introduction….4 West African Sufism in the Antebellum South….12 Developing Islamic Infrastructure….20 Bebop’s “Mohammedan Leanings”....23 Hard Bop Jihad….26 A Different Kind of Cat….37 Islam for the Soul of Jazz….41 Bibliography….51 4 Introduction The arrival of Christopher Columbus to the beaches of San Salvador did not only symbolize the New World’s first contact with white Christian Europeans- but black Muslims as well. Since 1492, Islam has been an essential, yet concealed presence in African diasporic identities. In the the continental US, Muslim slaves often held positions of power on plantations- and in several instances became leaders of revolts. Islam became a tool of resistance and resilience, and a way for a kidnapped people to preserve tradition, knowledge, and spirit. It should come as no surprise to learn that when Islam re-emerged in the African-American consciousness in the postbellum period 1, eventually in harmony with the Black Arts Movement, it not only retained these characteristics, but took on new meanings of prophetics, aesthetics, and resistance in cultural, spiritual, and political contexts. Even in the pre-9/11 dominant American narrative, images of Black Islam conjured up fearful and vague memories of the political and militant Nation of Islam of the 1960s. The popularity of Malcolm X’s autobiography brought this to the forefront of perceptions of Black Islam, and its place in the Black psyche was further cemented by Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

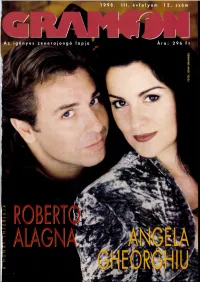

Gramofon, 1998 (3. Évfolyam, 1-12. Szám)

ROBERT® ALAGN«1 A FŐVÁROS RÁDIÓ J A 1 0 2 2 BUDAPEST, BIMBÓ ÚT 7 . TELEFON: 2 1 2 -4 5 0 7 , 2 1 2 - 5 6 4 3 • FAX: 3 1 6 - 2 0 7 3 G r a m o f o n a • / a l e m e z a / a n Hanglem ezipar k a r á c s o n y a Szakmai körökben ma már mindenki elismeri, Hogy a klasszikus ze nei Hanglemezkiadás a kilencvenes évek második felében világszerte súlyos válságba került. A zenekedvelők, a lemezvásárlók ugyanakkor még nem érzékelik ezt a krízist, sőt ellenkezőleg: a lemezboltok pol cai Montrealtól Wellingtonig és Buenos Airestől Tokióig mindenütt roskadoznak az újabb és újabb komolyzenei kiadványoktól, s ezek a CD-k egyre szebbek, egyre változatosabbak; igaz, egyre drágábbak is. A kínálat bővülését jelzi, Hogy miközben az egyetlen magyar Hanglemez-szaklap, a Gramofon (terjedelmi okokból) Hónapról Hó napra csupán arra vállalkozHat, Hogy ízelítőt adjon a legfrissebb és legértékesebb klasszikus és dzsesszkiadványokból, a londoni „nagy Zongora- testvér”, a Hetvenöt éve alapított GramopHone egymás után indítja speciális érdeklődést kielégítő, negyedéves magazinjait. A „Quart- versenyek lerlykben” ma már nemcsak operáról, zongoraművekről vagy kama razenéről, Hanem újabban fimzenéről és world musicról is olvas Hatunk. Látszólag teHát minden a legnagyobb rendben van, de mégis egyre- másra érkeznek Hírek arról, Hogy valamely patinás, nagy múltú le mezkiadó szerződést bontott sikeres (nemritkán világHírű) művészé vel, mert nem tudja foglalkoztatni többé; egyszerűen azért, mert pro dukciói iránt nincs megfelelő kereslet. ÉlHetünk a gyanúperrel, Hogy ezúttal is a világgazdaság történetéből már jól ismert túltermelési vál ozart ságnak leHetünk tanúi. -

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What You Are About to Read Is the Book of the Blog of the Facebook Project I Started When My Dad Died in 2019

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What you are about to read is the book of the blog of the Facebook project I started when my dad died in 2019. It also happens to be many more things: a diary, a commentary on contemporaneous events, a series of stories, lectures, and diatribes on politics, religion, art, business, philosophy, and pop culture, all in the mostly daily publishing of 365 essays, ostensibly about an album, but really just what spewed from my brain while listening to an album. I finished the last essay on June 19, 2020 and began putting it into book from. The hyperlinked but typo rich version of these essays is available at: https://albumsforeternity.blogspot.com/ Thank you for reading, I hope you find it enjoyable, possibly even entertaining. bottleofbeef.com exists, why not give it a visit? Have an album you want me to review? Want to give feedback or converse about something? Send your own wordy words to [email protected] , and I will most likely reply. Unless you’re being a jerk. © Bottle of Beef 2020, all rights reserved. Welcome to my record collection. This is a book about my love of listening to albums. It started off as a nightly perusal of my dad's record collection (which sadly became mine) on my personal Facebook page. Over the ensuing months it became quite an enjoyable process of simply ranting about what I think is a real art form, the album. It exists in three forms: nightly posts on Facebook, a chronologically maintained blog that is still ongoing (though less frequent), and now this book. -

Pharoah Searchin' Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pharoah Searchin' mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Searchin' Country: France Released: 1992 Style: Contemporary Jazz, Fusion, Free Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1917 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1492 mb WMA version RAR size: 1218 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 830 Other Formats: WAV MP3 AA APE MP1 AC3 DMF Tracklist Hide Credits Searchin' 1 6:44 Composed By – Serge Michel, Yvan Pinson A Day In Paris 2 10:44 Composed By – Yvan Pinson Djebel 3 7:06 Composed By – David Lelandais Yliph 4 5:52 Composed By – Philippe Gerbault, Yvan Pinson I Give You 5 7:48 Composed By – Bertrand Renaudin Farrell In A Trance 6 14:51 Composed By – Serge Michel Jazz Adytum 7 6:26 Composed By – Yvan Pinson Hum Allah 8 6:01 Composed By – Pharoah Sanders Companies, etc. Recorded At – Studio Sam Productions Mixed At – Studio Sam Productions Distributed By – Music Center Manufactured By – DADC Austria Credits Arranged By – Pharoah (tracks: 5, 8) Bass, Voice – David Lelandais Co-producer – François Daniel, Pharoah Design, Layout – Philippe Merienne Drums, Xylophone, Voice – Philippe Gerbault Flute, Percussion, Voice – Ludovic Ozier Guitar – Loïc Lelandais (tracks: 2) Illustration, Photography By – Guillaume Ertaud Management – Philippe Révillon Piano, Voice – Yvan Pinson Recorded By, Mixed By – François Daniel Recorded By, Mixed By [Assistant] – David Euverte Soprano Saxophone, Voice – Serge Michel Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SACEM / SDRM Matrix / Runout: SIAM-9219 14 A1 Related Music albums to Searchin' by Pharoah 1. Yvan Delporte Und Peyo / Margarita Meister - Der Kleine Schlumpf Reisst Aus 2. Pharoah Sanders - Tauhid 3. Junior Byles, The Upsetters - Pharoah Hiding 4. -

Sommaire Catalogue Jazz / Blues Octobre 2011

SOMMAIRE CATALOGUE JAZZ / BLUES OCTOBRE 2011 Page COMPACT DISCS Blues .................................................................................. 01 Multi Interprètes Blues ....................................................... 08 Jazz ................................................................................... 10 Multi Interprètes Jazz ......................................................... 105 SUPPORTS VINYLES Jazz .................................................................................... 112 DVD Jazz .................................................................................... 114 L'astérisque * indique les Disques, DVD, CD audio, à paraître à partir de la parution de ce bon de commande, sous réserve des autorisations légales et contractuelles. Certains produits existant dans ce listing peuvent être supprimés en cours d'année, quel qu'en soit le motif. Ces articles apparaîtront de ce fait comme "supprimés" sur nos documents de livraison. BLUES 1 B B KING B B KING (Suite) Live Sweet Little Angel – 1954-1957 Selected Singles 18/02/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN (SAGAJAZZ) (900)CD 18/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GACFBH=YYZZ\Y: #:GAAHFD=VUU]U[: Live At The BBC 19/05/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / EMARCY The birth of a king 10.CLASS.REP(SAGAJAZZ) (899)CD 23/08/2004 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / SAGA (949)CD #:GAAHFD=U[XVY^: #:GACEJI=WU\]V^: One Kind Favor 25/08/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GEFFEN Live At The Apollo(ORIGINALS (JAZZ)) (268)CD 28/04/2008 CLASSICS JAZZ FRANCE / GRP (899)CD #:GACFBH=]VWYVX: -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/55 - Total : 2125 Vinyls Au 25/09/2021 Collection "Jazz" De Cush

Collection "Jazz" de cush Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage A.r. Penck Going Through LP none Allemagne Aacm L'avanguardia Di Chicago LP BSRMJ 001 Italie Abbey Lincoln Painted Lady LP 1003 France Abraham Inc. Tweet Tweet LP LBLC 1711 EU Abus Dangereux Happy French Band LP JB 105 M7 660 France Acid Birds Acid Birds LP QBICO 85 Italie Acting Trio Acting Trio LP 529314 France Adam Rudolph's Moving Pictures... Glare Of The Tiger 2LP Inconnu Ahmad Jamal At The Blackhawk LP 515002 France Aidan Baker With Richard Baker... Smudging LP BW06 Italie Air Open Air Suite LP AN 3002 Etats Unis Amerique Air Live Air LP Inconnu Air Air Mail LP BSR 0049 Italie Air 8o° Below '82 LP 6313 385 France Al Basim Revival LP none Etats Unis Amerique Al Cohn Xanadu In Africa LP Xanadu 180 Etats Unis Amerique Al Cohn & Zoot Sims Either Way LP ZMS-2002 Etats Unis Amerique Alan Silva Skillfullness LP 1091 Etats Unis Amerique Alan Silva Inner Song LP CW005 France Alan Silva Alan Silva & The Celestial Com...3LP Actuel 5293042-43-44France Alan Silva And His Celestrial ... Luna Surface LP 529.312 France Alan Silva, The Celestrial Com... The Shout - Portrait For A Sma...LP Inconnu Alan Skidmore, Tony Oxley, Ali... Soh LP VS 0018 Allemagne Albert Ayler Witches & Devils LP FLP 40101 France Albert Ayler Vibrations LP AL 1000 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Village Concerts 2LP AS 9336/2 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Last Album LP AS 9208 France Albert Ayler The Last Album LP AS-9208 Etats Unis Amerique Albert Ayler The Hilversum Session LP 6001 Pays-Bas