Media Uses and Trust During Protests: a Working Paper on the Media Uses of Lebanese During the 2019 Uprising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: the War of Constructing Identities in the Digital Space and the Power of Discursive Practices

CONFLICT RESEARCH PROGRAMME Research at LSE Conflict Research Programme Syria: The war of constructing identities in the digital space and the power of discursive practices Bilal Zaiter About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme managed by the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit at the LSE and funded by the UK Department for International Development. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. About the Authors Bilal Zaiter is a Palestinian-Syrian researcher and social entrepreneur based in France. His main research interests are discursive and semiotics practices. He focuses on digital spaces and data. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the thoughtful discussions and remarkable support of both Dr. Rim Turkmani and Sami Hadaya from the Syrian team at LSE. They showed outstanding understanding not only to the particularities of the Syrian conflict but also to what it takes to proceed with such kind of multi-methods and multi-disciplinary work. They have been patient and it was great working with them. I would also like to thank the CRP for the grant they provided to conduct this study. Without the grant this work would not have been done. Special thanks to the three Syrian programmers and IT experts who worked with me to de- velop the software needed for my master’s degree research and for this research. They are living now in France, Germany and Austria. -

Hamas's Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter in a Recent

Hamas’s Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter In a recent interview with the pro-Syrian Al Mayadeen channel based in Beirut, the Hamas deputy chief, Mousa Abu Marzouk asserted in October 2013 that Khaled Meshaal was ‘wrong’ to have raised the flag of the Syrian revolution on his historic return to Gaza at the end of last year.1 While on the face of it, Marzouk’s comment may not in itself hold much significance, referring only to the literal act of raising the flag, an inadvertent error made during an exuberant rally in which a number of other flags were also raised, subsequent remarks by Marzouk during the course of the interview describing the Syrian state as the ‘beating heart of the Palestinian cause’ and acknowledging the previous ‘favour’ of the Syrian regime towards the movement2 may be more indicative of shift in Hamas’s position of open opposition towards the Asad regime. This raises the important question of whether we are now witnessing a third phase in Hamas’s response towards the Syrian Uprising. In the first stage of its response, a period lasting from the outbreak of hostilities in the southern city of Deraa in March 2011 until December 2011, Hamas’s position appeared to be one of constructive ambiguity, publicly refraining from condemning Syrian authorities, but studiously avoiding anything which could have been interpreted as an open act of support for the Syrian regime. Such a position clearly stemmed from Hamas’s own vulnerabilities, acting with caution for fear of exacting reprisals against the movement still operating out of Damascus. -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

Hezbollah's Concept of Deterrence Vis-À-Vis Israel According to Nasrallah

Hezbollah’s Concept of Deterrence vis-à-vis Israel according to Nasrallah: From the Second Lebanon War to the Present Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer “Lebanon must have a deterrent military strength…then we will tell the Israelis to be careful. If you want to attack Lebanon to achieve goals, you will not be able to, because we are no longer a weak country. If we present the Israelis with such logic, they will think a million times.” Hassan Nasrallah, August 17, 2009 This essay deals with Hezbollah’s concept of deterrence against Israel as it developed over the ten years since the Second Lebanon War. The essay looks at the most important speeches by Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah during this period to examine the evolution and development of the concept of deterrence at four points in time that reflect Hezbollah’s internal and regional milieu (2000, 2006, 2008, and 2011). Over the years, Nasrallah has frequently utilized the media to deliver his messages and promote the organization’s agenda to key target audiences – Israel and the internal Lebanese audience. His speeches therefore constitute an opportunity for understanding the organization’s stances in general and its concept of deterrence in particular. The Quiet Decade: In the Aftermath of the Second Lebanon War, 2006-2016 I 115 Edited by Udi Dekel, Gabi Siboni, and Omer Einav 116 I Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer Principal Messages An analysis of Nasrallah’s speeches, especially since 2011, shows that he has devoted them primarily to the war in Syria and internal Lebanese politics. -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

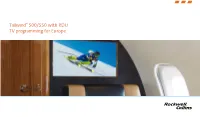

Tailwind® 500/550 with RDU TV Programming for Europe

Tailwind® 500/550 with RDU TV programming for Europe European Programming 23 CNBC Europe E 57 WDR Köln G 91 N24 Austria G 125 EinsPlus G ® for Tailwind 500/550 with RDU 24 Sonlife Broadcasting Network E 58 WDR Bielefeld G 92 rbb Berlin G 126 PHOENIX G A Arabic G German P Portuguese 25 Russia Today E 59 WDR Dortmund G 93 rbb Brandenburg G 127 SIXX G D Deutch K Korean S Spanish 26 GOD Channel E 60 WDR Düsseldorf G 94 NDR FS MV G 128 sixx Austria G E English M Multi T Turkish F French Po Polish 27 BVN TV D 61 WDR Essen G 95 NDR FS HH G 129 TELE 5 G 28 TV Record SD P 62 WDR Münster G 96 NDR FS NDS G 130 DMAX G Standard Definition Free-to-Air channel 29 TELESUR S 63 WDR Siegen G 97 NDR FS SH G 131 DMAX Austria G 30 TVGA S 64 Das Erste G 98 MDR Sachsen G 132 SPORT1 G The following channel list is effective April 21, 2016. Channels listed are subject to change 31 TBN Espana S 65 hr-fernsehen G 99 MDR S-Anhalt G 133 Eurosport 1 Deutschland G without notice. 32 TVE INTERNACIONAL EUROPA S 66 Bayerisches FS Nord G 100 MDR Thüringen G 134 Schau TV G Astra 33 CANAL 24 HORAS S 67 Bayerisches FS Süd G 101 SWR Fernsehen RP G 135 Folx TV G 34 Cubavision Internacional S 68 ARD-alpha G 102 SWR Fernsehen BW G 136 SOPHIA TV G 1 France 24 (in English) E 35 RT Esp S 69 ZDF G 103 DELUXE MUSIC G 137 Die Neue Zeit TV G 2 France 24 (en Français) F 36 Canal Algerie F 70 ZDFinfo G 104 n-tv G 138 K-TV G 3 Al Jazeera English E 37 Algerie 3 A 71 zdf_neo G 105 RTL Television G 139 a.tv G 4 NHK World TV E 38 Al Jazeera Channel A 72 zdf.kultur G 106 RTL FS G 140 TVA-OTV -

Channel No. Channel National UAE 2 Abu Dhabi 3 Abu Dhabi TV Plus 1 4

Channel No. Channel National UAE 2 Abu Dhabi 3 Abu Dhabi TV Plus 1 4 Al Emarat 5 Dubai TV HD 6 Noor Dubai 7 Sama Dubai 8 Sharjah TV 9 Ajman TV 12 Al Dafrah News News- Arabic 25 Sky News Arabia 26 BBC Arabic 27 France 24 28 Ekhbariya 29 CNBC Arabia 30 TRT Arabia 31 Al Mayadeen News- International 55 NHK 63 Russia Today News- South Asian 87 E-News 89 Manorama News 90 People TV 96 ARY News 93 India Vision Movies Movies- English 113 Fox Movies Movies- Arabic 152 Rotana Cinema 153 Rotana Aflam 154 Rotana Classic (Rotana Zaman) 161 Nile Cinema 162 Al Hayat Cinema 163 Panorama Film Movies- South Asian 171 B4U Aflam 172 Zee Film Hindi 173 Zee Aflam 174 Zee Alwan 189 Imagine Movies Series TV Series- English 201 Dubai One TV 206 Decision Maker TV 207 Fox 244 Abu Dhabi Drama 257 Al Kahera Wal Nas 258 Rotana Khalijiah 259 Rotana Al Masriya 261 Capital Broadcast Center 262 CBC Drama 263 Panorama Drama 703 Nile Drama 267 Al Nahar 268 Al Nahar Drama 269 Al Nahar +2 (Al Nahar Drama 2) 270 AlHayat 271 Al Hayat 2 272 Al Hayat Mosalsalaat 274 Funoon TV 275 Moga Comedy TV Series- South Asian 303 Jeevan TV 304 Jai Hind TV 305 Amrita TV 313 Channel i 316 B4U Plus 322 Urdu TV Kids 324 Yes IndiaVision Kids- Arabic 351 Space Toon 353 Al Jazeera Baraem 354 Toyour Al Jannah 356 Cartoon Net Arabia 357 Karameesh TV Kids- English Documentaries 378 National Geographic Abu Dhabi Style & Entertainment 401 Fatafeat 405 ARY Zauq 412 Physique TV HD 415 Ikono HD 425 City 7 427 Fashion One HD 429 E-24 430 Citrus TV Music Music - English 433 du Live! (DuBarker2) 434 Channel -

Assad Strikes Damascus

January 2014 Valerie Szybala MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 16 ASSAD STRIKES DaMASCUS THE BATTLE FOR SYRIA’S CAPItal Cover: A man walks in front of a burning building after a Syrian Air force air strike in Ain Tarma neighbourhood of Damascus. Picture taken January 27, 2013. REUTERS/Goran Tomasevic/Files All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2014 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2014 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Valerie Szybala MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 16 ASSAD STRIKES DaMASCUS THE BATTLE FOR SYRIA’S CAPItal ABOUT THE AUTHOR Valerie Szybala is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where she focuses on the conflict in Syria. Valerie was in Damascus studying Arabic when the uprising began in 2011, giving her a unique understanding of the ensuing developments. Valerie came to ISW from Chemonics International Inc., where she supported the implementation of USAID-funded development projects in the Middle East. Her prior experience includes analysis of civilian casualties from coalition air strikes in Afghanistan for Dr. Jason Lyall at Yale University, and research on peace process policy with the Israeli-Palestine Center for Research and Information (IPCRI) in Jerusalem. Valerie also worked for several years at the American Council of Young Political Leaders, a nonpartisan NGO dedicated to promoting understanding among the next generation of international leaders. -

AM/LANG 450 Advanced High Modern

CET Syllabus of Record Program: Intensive Arabic Language in Amman / Middle East Studies & Internship in Amman Course Code / Title: (AM/LANG 450) Advanced High Modern Standard Arabic Total Hours: 105 Recommended Credits: 6 Primary Discipline: Arabic Language Language of Instruction: Arabic Prerequisites / Requirements: ACTFL advanced high to superior level equivalent. Final placement at discretion of Academic Director Description This course is offered to students who: ● Can comprehend advanced-level authentic materials including poetry, short stories, and novels ● Organize discourse appropriately using advanced vocabulary and native cultural references in order to engage in a broad range of debates and discussions with native speakers ● Write research papers that are clearly organized with significant length and complexity, utilizing advanced-level connectors rich with content in the areas of culture, economics, religion, politics and society ● Understand the details of major news broadcasts ● Speak with sufficient structural accuracy and vocabulary to participate effectively in most formal and informal conversations about practical, social and professional topics The course provides students with high-level cultural content to present opinions, support and critique arguments, and attain a level of linguistic fluidity to discuss theoretical subjects outside their areas of expertise. Through the course, students produce language free from errors and clearly understandable to native speakers from different generations and socio-economic backgrounds who do not have experience communicating with non-native Arabic speakers. Materials for this course are limited to those designed for native speakers of Arabic. Driven by the concept of communicative proficiency and the goal of functional competency, CET Jordan programs treat Arabic language as one system of communication, guiding students to employ the appropriate register to perform a variety of real-life communicative functions. -

WFP Assistance Trucked from Turkey Into Al-Hasakeh Food Deliveriesbegin Under Two-Month Aid Programme for Syria’S Aleppo Governorate HIGH

WFP SYRIA CRISIS RESPONSE Situation Update 14 - 27 May 2014 SYRIA JO RDAN LEBANON TURKEY IRAQ EGYPT HIGHLIGHTS Food deliveries begin under two-month aid programme for Syria’s Aleppo governorate More WFP assistance trucked from Turkey into Al-Hasakeh Access to hard-to-reach areas of Homs and Rural Damascus briefly restored Review of support to non-camp refugees in Jordan underway Egypt voucher programme extended to Tanta city WFP/Laure Chadraoui For information on WFP’s Syria Crisis Response in 2013 and 2014, please use the QR Code or access through the link wfp.org/syriainfo SYRIA WFP RESUMES FOOD DELIVERIES TO RURAL ALEPPO Successful deliveries of food assistance and critical humanitarian supplies to besieged and hard-to-reach villages in rural Aleppo through two consecutive humanitarian convoys have enabled the UN to further widen humanitarian access in areas not reached since July 2013. WFP and other humanitarian actors have developed a two-month plan to deliver more assistance to various locations in the governorate. WFP/Zenah Elmohandes The plan aims to provide food and other critical supplies for approximately 800,000 people in the governorate, including 160,000 people in rural Aleppo and eastern Aleppo city. Dispatches under the plan started on 26 May delivering almost 6,000 WFP family food rations – sufficient for 30,000 people for one month –in Manbej, Al Bab and Maskanah. On 29-30 May a further 5,250 WFP rations – for 26,000 people – were delivered via inter-agency convoy to Orem, Afrin, Azaz and Tell Rifat in western rural Aleppo WATER SHORTAGES IMPACT BREAD PRODUCTION IN THE GOVERNORATE’S MAIN CITY Disruption of mains water supplies in Aleppo city contributed to a drop in bread production during the reporting period. -

AFAC Film Week 2014 March 4 – 11

AFAC Film Week 2014 March 4 – 11 At Metropolis Empire Sofil, Achrafieh, Beirut 1 Since AFAC’s inception in 2007, we have been dedicated to supporting independent Arab filmmakers and there are over 150 film projects that have benefited from AFAC’s funding to date. A significant mass has Context accumulated in the region’s contemporary cinema production. And yet, Arab audiences are largely out of the picture, as most films enter the festival circuits and then disappear into oblivion. In 2014, AFAC has launched its first AFAC Film Week, a travelling exhibition of AFAC-supported films which will be hosted in a different Arab city every year and aims to offer independent Arab filmmakers an engaging cultural platform through which to connect with local audiences. The issue of film distribution continues to be an ongoing concern that demands serious attention. The AFAC Film Week is but a small step towards honoring and showcasing the works of independent Arab filmmakers that have been awarded AFAC grants and support. 2 We present the AFAC Film Week as a modest compensation for the general lack of distribution and visibility available for independent Arab film productions. Filmmakers spend years of toil and creativity to Concept produce their cinematic productions, only to be offered disappointingly limited opportunities for viewership and interaction. Their voices are left unheard and they are unable to connect with their natural audiences, all despite the real efforts taking place, from individuals and local film organizations alike, in seeking out traditional and alternative means of film distribution for the Arab region.