Media Industries in Revolutionary Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: the War of Constructing Identities in the Digital Space and the Power of Discursive Practices

CONFLICT RESEARCH PROGRAMME Research at LSE Conflict Research Programme Syria: The war of constructing identities in the digital space and the power of discursive practices Bilal Zaiter About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme managed by the Conflict and Civil Society Research Unit at the LSE and funded by the UK Department for International Development. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. About the Authors Bilal Zaiter is a Palestinian-Syrian researcher and social entrepreneur based in France. His main research interests are discursive and semiotics practices. He focuses on digital spaces and data. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the thoughtful discussions and remarkable support of both Dr. Rim Turkmani and Sami Hadaya from the Syrian team at LSE. They showed outstanding understanding not only to the particularities of the Syrian conflict but also to what it takes to proceed with such kind of multi-methods and multi-disciplinary work. They have been patient and it was great working with them. I would also like to thank the CRP for the grant they provided to conduct this study. Without the grant this work would not have been done. Special thanks to the three Syrian programmers and IT experts who worked with me to de- velop the software needed for my master’s degree research and for this research. They are living now in France, Germany and Austria. -

Hamas's Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter in a Recent

Hamas’s Response to the Syrian Uprising Nasrin Akhter In a recent interview with the pro-Syrian Al Mayadeen channel based in Beirut, the Hamas deputy chief, Mousa Abu Marzouk asserted in October 2013 that Khaled Meshaal was ‘wrong’ to have raised the flag of the Syrian revolution on his historic return to Gaza at the end of last year.1 While on the face of it, Marzouk’s comment may not in itself hold much significance, referring only to the literal act of raising the flag, an inadvertent error made during an exuberant rally in which a number of other flags were also raised, subsequent remarks by Marzouk during the course of the interview describing the Syrian state as the ‘beating heart of the Palestinian cause’ and acknowledging the previous ‘favour’ of the Syrian regime towards the movement2 may be more indicative of shift in Hamas’s position of open opposition towards the Asad regime. This raises the important question of whether we are now witnessing a third phase in Hamas’s response towards the Syrian Uprising. In the first stage of its response, a period lasting from the outbreak of hostilities in the southern city of Deraa in March 2011 until December 2011, Hamas’s position appeared to be one of constructive ambiguity, publicly refraining from condemning Syrian authorities, but studiously avoiding anything which could have been interpreted as an open act of support for the Syrian regime. Such a position clearly stemmed from Hamas’s own vulnerabilities, acting with caution for fear of exacting reprisals against the movement still operating out of Damascus. -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund

7/2019 From Cold War to Civil War: 75 Years of Russian-Syrian Relations — Aron Lund PUBLISHED BY THE SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS | UI.SE Abstract The Russian-Syrian relationship turns 75 in 2019. The Soviet Union had already emerged as Syria’s main military backer in the 1950s, well before the Baath Party coup of 1963, and it maintained a close if sometimes tense partnership with President Hafez al-Assad (1970–2000). However, ties loosened fast once the Cold War ended. It was only when both Moscow and Damascus separately began to drift back into conflict with the United States in the mid-00s that the relationship was revived. Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Russia has stood by Bashar al-Assad’s embattled regime against a host of foreign and domestic enemies, most notably through its aerial intervention of 2015. Buoyed by Russian and Iranian support, the Syrian president and his supporters now control most of the population and all the major cities, although the government struggles to keep afloat economically. About one-third of the country remains under the control of Turkish-backed Sunni factions or US-backed Kurds, but deals imposed by external actors, chief among them Russia, prevent either side from moving against the other. Unless or until the foreign actors pull out, Syria is likely to remain as a half-active, half-frozen conflict, with Russia operating as the chief arbiter of its internal tensions – or trying to. This report is a companion piece to UI Paper 2/2019, Russia in the Middle East, which looks at Russia’s involvement with the Middle East more generally and discusses the regional impact of the Syria intervention.1 The present paper seeks to focus on the Russian-Syrian relationship itself through a largely chronological description of its evolution up to the present day, with additional thematically organised material on Russia’s current role in Syria. -

World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa Building New Platforms of Cooperation

Regional Agenda World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa Building New Platforms of Cooperation Dead Sea, Jordan 6-7 April 2019 Contents Preface Preface 3 Meeting highlights 4 Co-Chairs 6 News from the Dead Sea 8 The Fourth Industrial Revolution in the Arab 12 World Shaping a New Economic Model 18 Stewardship for the Regional Commons 24 Mirek Dušek Finding Common Ground in a 30 Deputy Head of the Centre for Multiconceptual World Geopolitical and Regional Affairs Member of the Executive Committee Tackling regional challenges with start-ups 36 World Economic Forum Acknowledgements 40 Digital update 42 Contributors 43 Maroun Kairouz Community Lead, Regional Strategies, MENA Global Leadership Fellow World Economic Forum World Economic Forum ® © 2019. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system. This report is Cradle-to-Cradle printed with sustainable materials 2 World Economic Forum on the Middle East and North Africa As the world economy enters By fostering the appropriate In addition, the Forum’s community Globalization 4.0 – driven by conditions as the Fourth Industrial of Global Shapers from the region emerging technologies and Revolution takes root, policy-makers convened ahead of the meeting to ubiquitous data – the Middle East and leaders can leverage the learn about actions that can be taken and North Africa seeks to leverage momentum of reform in many of the towards restoration of the natural this new era and forge its own path region’s countries to create the right environment as part of the fight for societal and economic ecosystem for business, civil society against climate change. -

A Bakhtinian Reading of Contemporary Jordanian Political Humour

Carnivalesque politics and popular resistance: A Bakhtinian reading of contemporary Jordanian political humour Yousef Barahmeh Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth School of Area Studies, History, Politics and Literature February 2020 i Abstract This thesis examines contemporary Jordanian political humour in the context of the political history of Jordan and the 2011 Arab Spring revolutions. It applies Mikhail Bakhtin’s mid-20th century theory of carnival and the carnivalesque (folk humour) as a framework for thinking about Jordanian politics and political humour in social media spaces following the Arab Spring. The Bakhtinian approach to humour has predominantly focused on the role of humour as a revolutionary impulse that aims to attack and expose the shortcomings of established political power, as well as to highlight public attitudes towards that power. The analysis undertaken here of Jordanian politics and political humour in Jordanian social media spaces after the Arab Spring found that Bakhtin’s ‘marketplace’ is no longer the streets and material public spaces, but rather the social media spaces. The nature of the carnivals in social media spaces is in many ways just as carnivalesque as the ‘marketplace’ of Bakhtin’s Medieval France, characterised by polyphony, the overturning of social hierarchies and the presence of dialogism (and monologism) and the grotesque. To more fully address the relevance – and some of the limitations – of application of Bakhtin’s ideas about carnival to the Jordanian socio- political context after the Arab Spring, this thesis analyses key political cartoons, satirical articles, comedy sketches, politically satirical videos and internet memes produced by Jordanians from the start of the Arab ii Spring to early 2019. -

George Saltsman Curriculum Vitae

George Saltsman Curriculum Vitae Postal: 9900 Brookwood Ln. College Station, TX 77845 Phone: (325) 829-5872 Web: www.georgesaltsman.com Email: [email protected] Education Ed.D. Educational Leadership. Lamar University (2014) Awarded: Outstanding doctoral student Dissertation: Global Leadership Competencies in Education: A Delphi Study of UNESCO Delegates and Administrators (Conducted in English, French, and Spanish) M.S. Organizational & Human Resource Development. Abilene Christian University (1995) B.S. Computer Science. Abilene Christian University (1990) Professional Employment Director, Center for Educational Innovation and Digital Learning Lamar University: Office of the President 9/2016 - Present Continuation of all previous duties as Director, Educational Innovation. New duties include the establishment and administration of the Center for Educational Innovation and Digital Learning. Currently establishing a $50M USD program, at the request of the Prime Minister of Vietnam, to provide computer science bootcamp training to 200,000 individuals in eight locations. Content and curriculum are sourced and currently in pilot stage. Current activity now involves extending curriculum into secondary and post- secondary institutions. Expected additional funding from Government of Vietnam, Microsoft, Amazon, IBM, and the Prince Andrew Charitable Trust. Currently establishing an Education Design Center, located in Austin Texas, to assist PK-12 school leaders in selecting appropriate pedagogy, training, technology, and educational support -

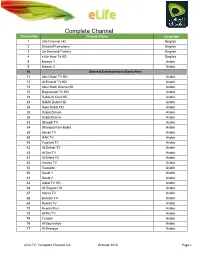

Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1

Complete Channel Channel No. List Channel Name Language 1 Info Channel HD English 2 Etisalat Promotions English 3 On Demand Trailers English 4 eLife How-To HD English 8 Mosaic 1 Arabic 9 Mosaic 2 Arabic 10 General Entertainment Starts Here 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic 25 Dubai Zaman Arabic 26 Dubai Drama Arabic 33 Sharjah TV Arabic 34 Sharqiya from Kalba Arabic 38 Ajman TV Arabic 39 RAK TV Arabic 40 Fujairah TV Arabic 42 Al Dafrah TV Arabic 43 Al Dar TV Arabic 51 Al Waha TV Arabic 52 Hawas TV Arabic 53 Tawazon Arabic 60 Saudi 1 Arabic 61 Saudi 2 Arabic 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic 67 Oman TV Arabic 68 Bahrain TV Arabic 69 Kuwait TV Arabic 70 Kuwait Plus Arabic 73 Al Rai TV Arabic 74 Funoon Arabic 76 Al Soumariya Arabic 77 Al Sharqiya Arabic eLife TV : Complete Channel List October 2015 Page 1 Complete Channel 79 LBC Sat List Arabic 80 OTV Arabic 81 LDC Arabic 82 Future TV Arabic 83 Tele Liban Arabic 84 MTV Lebanon Arabic 85 NBN Arabic 86 Al Jadeed Arabic 89 Jordan TV Arabic 91 Palestine Arabic 92 Syria TV Arabic 94 Al Masriya Arabic 95 Al Kahera Wal Nass Arabic 96 Al Kahera Wal Nass +2 Arabic 97 ON TV Arabic 98 ON TV Live Arabic 101 CBC Arabic 102 CBC Extra Arabic 103 CBC Drama Arabic 104 Al Hayat Arabic 105 Al Hayat 2 Arabic 106 Al Hayat Musalsalat Arabic 108 Al Nahar TV Arabic 109 Al Nahar TV +2 Arabic 110 Al Nahar Drama Arabic 112 Sada Al Balad Arabic 113 Sada Al Balad -

CONTEMPORARY ART the Visual Language of Dissent

Volume 11 - Number 1 December 2014 – January 2015 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: CCONTEMPORARYONTEMPORARY AARTRT ● TThehe vvisualisual languagelanguage ofof dissentdissent ● UUn-representablen-representable narrativesnarratives andand contemporarycontemporary amnesiaamnesia ● WWaysays ooff sseeingeeing ● AArabrab aanimatednimated ccartoons,artoons, thenthen andand nownow ● PPhotohoto ccompetitionompetition resultsresults ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 11 - Number 1 DecemberDe 2014 – January 2015 £4 TTHISHIS IISSUESSUE: CCONTEMPORARYONTEMPORARY AARTRT ● TThehe vvisualisual llanguageanguage ooff ddissentissent ● UUn-representablen-representable nnarrativesarratives aandnd contemporarycontemporary aamnesiamnesia ● WWaysays ooff sseeingeeing ● AArabrab aanimatednimated ccartoons,artoons, tthenhen aandnd nnowow ● PPhotohoto ccompetitionompetition rresultsesults ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents iinn LLondonondon Samira Alikhanzadeh, Untitled, 2011 About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) Volume 11 - Number 1 Th e London Middle East Institute (LMEI) draws upon the resources of London and SOAS to provide December 2014 – teaching, training, research, publication, consultancy, outreach and other services related to the Middle January 2015 East. It serves as a neutral forum for Middle East studies broadly defi ned and helps to create links between individuals and institutions with academic, commercial, diplomatic, media or other specialisations. With its own professional staff of Middle East experts, -

Hezbollah's Concept of Deterrence Vis-À-Vis Israel According to Nasrallah

Hezbollah’s Concept of Deterrence vis-à-vis Israel according to Nasrallah: From the Second Lebanon War to the Present Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer “Lebanon must have a deterrent military strength…then we will tell the Israelis to be careful. If you want to attack Lebanon to achieve goals, you will not be able to, because we are no longer a weak country. If we present the Israelis with such logic, they will think a million times.” Hassan Nasrallah, August 17, 2009 This essay deals with Hezbollah’s concept of deterrence against Israel as it developed over the ten years since the Second Lebanon War. The essay looks at the most important speeches by Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah during this period to examine the evolution and development of the concept of deterrence at four points in time that reflect Hezbollah’s internal and regional milieu (2000, 2006, 2008, and 2011). Over the years, Nasrallah has frequently utilized the media to deliver his messages and promote the organization’s agenda to key target audiences – Israel and the internal Lebanese audience. His speeches therefore constitute an opportunity for understanding the organization’s stances in general and its concept of deterrence in particular. The Quiet Decade: In the Aftermath of the Second Lebanon War, 2006-2016 I 115 Edited by Udi Dekel, Gabi Siboni, and Omer Einav 116 I Carmit Valensi and Yoram Schweitzer Principal Messages An analysis of Nasrallah’s speeches, especially since 2011, shows that he has devoted them primarily to the war in Syria and internal Lebanese politics. -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

1 GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction

GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 1. Introduction GALE Phase 3 Arabic Broadcast News Speech Part 1 contains approximately 132 hours of Arabic broadcast news speech collected in 2007 by the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC), MediaNet, Tunis, Tunisia and MTC, Rabat, Morocco during Phase 3 of the DARPA GALE program. Broadcast audio for the DARPA GALE (Global Autonomous Language Exploitation) program was collected at LDC’s Philadelphia, PA USA facilities and at three remote collection sites: Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), Hong Kong (Chinese); Medianet (Arabic); and MTC (Arabic). The combined local and outsourced broadcast collection supported GALE at a rate of approximately 300 hours per week of programming from more than 50 broadcast sources for a total of over 30,000 hours of collected broadcast audio over the life of the program. The broadcast news recordings in this release feature news broadcasts focusing principally on current events from the following sources: Abu Dhabi TV, a television station based in Abu Dhabi, Al Alam News Channel, based in Iran; Al Arabiya, a news television station based in Dubai; Al Iraqiyah, an Iraqi television station; Aljazeera , a regional broadcaster located in Doha, Qatar; Al Ordiniyah, a national broadcast station in Jordan; Dubai TV, a broadcast station in the United Arab Emirates; Kuwait TV, a national broadcast station in Kuwait; Lebanese Broadcasting Corporation, a Lebanese television station; Nile TV, a broadcast programmer based in Egypt, Saudi TV, a national television station based in Saudi Arabia; and Syria TV, the national television station in Syria. 2. Broadcast Audio Data Collection Procedure LDC’s local broadcast collection system is highly automated, easily extensible and robust and capable of collecting, processing and evaluating hundreds of hours of content from several dozen sources per day.