1614727366480.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yes. That Is Moondragon. And, Yes. She Is Eating London

15 JUNE ES HAT IS Y . T MOONDRAGON. AND, YES. SHE IS EATING LONDON. DISMUKE Book 15 Enigma, Moondragon and Spider-Woman successfully stopped a multi- pronged scheme at the United Nations. Now, ΩFORCE is eager to track down Psionex at their London lair to find out more about their powerful benefactor, whoever that might be. But first, the web of players in this game of international superpower management must be untangled by ... K’OS MOONDRAGON STRONGHOLD COSMIC BLASTING MAJOR TELEPATH; MULTIPOWERED IMMORTAL GENIUS SHAO-LOM MASTER WARSKRULL PSIONEX SPIDER-WOMAN ENIGMA MEGA-ENHANCED ELUSIVE LATVERIAN SHIELD AGENT SUPER SPY ASYLUM CORONARY DARKFORCE METABOLIC MANIPULATION CONTROL DR. SOUND SONIC WIELDING STREET BRAWLER PRETTY IMPULSE MATHEMANIAC PERSUASIONS SUPER FAST MIND BOGGLING UM. STIMULATING. SUPER SHARP TELEPATH THE OFFICE OF WILSON FISK, MANHATTAN WILSON FISK STOOD facing the window. He looked out upon the island of Manhattan. Towering buildings. Billions of dollars of real estate. He owned about 5% of it. It would have been 25% if the U.N. scheme had succeeded. “You look like you are brooding,” a voice said that limped into Fisk’s office. Fisk turned to face Crossfire. “You look like you are wounded.” “Well,” Lucia Von Bardas said as she walked into the office brushing by Crossfire. “You both look like you have egg in your face. I can’t imagine how much money you lost in this endeavor. Ultrasonic hypnotic technology. Payoffs to U.N. staffers. Armored super mercenaries. High price to pay for failure.” Fisk didn’t show an overt reaction. “You act like you didn’t lose anything yourself, Prime Minister.” “No monetary loss. -

Tsr6903.Mu7.Ghotmu.C

[ Official Game Accessory Gamer's Handbook of the Volume 7 Contents Arcanna ................................3 Puck .............. ....................69 Cable ........... .... ....................5 Quantum ...............................71 Calypso .................................7 Rage ..................................73 Crimson and the Raven . ..................9 Red Wolf ...............................75 Crossbones ............................ 11 Rintrah .............. ..................77 Dane, Lorna ............. ...............13 Sefton, Amanda .........................79 Doctor Spectrum ........................15 Sersi ..................................81 Force ................................. 17 Set ................. ...................83 Gambit ................................21 Shadowmasters .... ... ..................85 Ghost Rider ............................23 Sif .................. ..................87 Great Lakes Avengers ....... .............25 Skinhead ...............................89 Guardians of the Galaxy . .................27 Solo ...................................91 Hodge, Cameron ........................33 Spider-Slayers .......... ................93 Kaluu ....... ............. ..............35 Stellaris ................................99 Kid Nova ................... ............37 Stygorr ...............................10 1 Knight and Fogg .........................39 Styx and Stone .........................10 3 Madame Web ...........................41 Sundragon ................... .........10 5 Marvel Boy .............................43 -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

Postfeminism in Female Team Superhero Comic Books by Showing the Opposite of The

POSTFEMINISM IN FEMALE TEAM SUPERHERO COMIC BOOKS by Elliott Alexander Sawyer A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Communication The University of Utah August 2014 Copyright © Elliott Alexander Sawyer 2014 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The following faculty members served as the supervisory committee chair and members for the thesis of________Elliott Alexander Sawyer__________. Dates at right indicate the members’ approval of the thesis. __________Robin E. Jensen_________________, Chair ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved _________Sarah Projansky__________________, Member ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved _________Marouf Hasian, Jr.________________, Member ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved The thesis has also been approved by_____Kent A. Ono_______________________ Chair of the Department/School/College of_____Communication _______ and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Comic books are beginning to be recognized for their impact on society because they inform, channel, and critique cultural norms. This thesis investigates how comic books interact and forward postfeminism. Specifically, this thesis explores the ways postfeminism interjects itself into female superhero team comic books. These comics, with their rosters of only women, provide unique perspectives on how women are represented in comic books. Additionally, the comics give insight into how women bond with one another in a popular culture text. The comics critiqued herein focus on transferring postfeminist ideals in a team format to readers, where the possibilities for representing powerful connections between women are lost. Postfeminist characteristics of consumption, sexual freedom, and sexual objectification are forwarded in the comic books, while also promoting aspects of racism. -

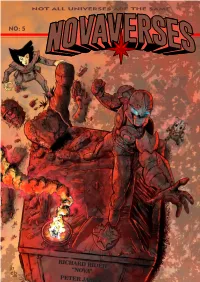

NOVAVERSES ISSUE 5D

NOT ALL UNIVERSES ARE THE SAME NO: 5 NOT ALL UNIVERSES ARE THE SAME RISE OF THE CORPS Arc 1: Whatever Happened to Richard Rider? Part 1 WRITER - GORDON FERNANDEZ ILLUSTRATION - JASON HEICHEL and DAZ RED DRAGON PART 3 WRITER - BRYAN DYKE ILLUSTRATION - FERNANDO ARGÜELLO STARSCREAM PART 5 WRITER - DAZ BLACKBURN ILLUSTRATION - EMILIANO CORREA, JOE SINGLETON and DAZ DREAM OF LIVING JUSTICE PART 2 WRITER - BYRON BREWER ILLUSTRATION - JASON HEICHEL Edited by Daz Blackburn, Doug Smith & Byron Brewer Front Cover by JASON HEICHEL and DAZ BLACKBURN Next Cover by JOHN GARRETSON Novaverses logo designed by CHRIS ANDERSON NOVA AND RELATED MARVEL CHARACTERS ARE DULY RECOGNIZED AS PROPERTY AND COPYRIGHT OF MARVEL COMICS AND MARVEL CHARACTERS INC. FANS PRODUCING NOVAVERSES DULY RECOGNIZE THE ABOVE AND DENOTE THAT NOVAVERSES IS A FAN-FICTION ANTHOLOGY PRODUCED BY FANS OF NOVA AND MARVEL COSMIC VIA NOVA PRIME PAGE AND TEAM619 FACEBOOK GROUP. NOVAVERSES IS A NON-PROFIT MAKING VENTURE AND IS INTENDED PURELY FOR THE ENJOYMENT OF FANS WITH ALL RESPECT DUE TO MARVEL. NOVAVERSES IS KINDLY HOSTED BY NOVA PRIME PAGE! ORIGINAL CHARACTERS CREATED FOR NOVAVERSES ARE THE PSYCHOLOGICAL COSMIC CONSTANT OF INDIVIDUAL CREATORS AND THEIR CENTURION IMAGINATIONS. DOWNLOAD A PDF VERSION AT www.novaprimepage.com/619.asp READ ONLINE AT novaprime.deviantart.com Rise of the Nova Corps obert Rider walked somberly through the city. It was a dark, bleak, night, and there weren't many people left on the streets. His parents and friends all warned him about the dangers of 1 Rwalking in this neighborhood, especially at this hour, but Robert didn't care. -

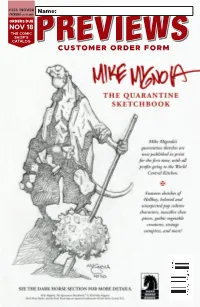

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

THIS DYING SUMMER by Evan Griffith Fiction Honors Thesis

THIS DYING SUMMER by Evan Griffith Fiction Honors Thesis Department of English University of North Carolina 2014 “On these magic shores children at play are for ever beaching their coracles. We too have been there; we can still hear the sound of the surf, though we shall land no more.” ― J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan 2 CONTENTS Tunnels 4 The Attic 17 Chlorine 22 Angels Ministry 34 Stars 45 Heroes 49 Curtain 61 Reunion 66 House of Cards 76 Break Point 79 3 TUNNELS Rob was the one who first suggested taking poetry down to the tunnels. “It’ll be like Dead Poet’s Society, or something. Did you see that movie?” “Rob, you’re a genius,” John had said, eyes glowing with inspiration. “We can read Whitman and shit.” He said shit a bit awkwardly, as if it didn’t quite fit his lilting voice, still caught in the throes of a pubescent flux. It was hopeful to Rob, though, all the same – shit was everything beyond Whitman. It was John’s promise of a world of novelty lurking there just below the ground, a world where Rob was a genius and John swore like he never gave a shit. They had found the tunnels in the woods behind school one afternoon while skipping math class – Rob anxiously consulting his watch, John forging ahead and feigning disinterest in school policies with mild success. John’s legs were still too gangly for any true display of confidence, but he was the undisputed leader all the same. He stood the tallest, and the veins in his forearms were near-cerulean blue. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

February Comic Previews Recommendation Lists

February Comic Previews Recommendation Lists Marvel Customer No # Name: STAR WARS DOCTOR APHRA #1 DOCTOR APHRA is back on the job! She's been keeping a low profile - jobs are scarce and credits scarcer. But the promise of the score of a lifetime is a $3.99 chance too good for her to pass up. And to find the cursed RINGS OF VAALE, Aphra will need a crew of treasure hunters the likes of which the galaxy has never seen before! But RONEN TAGGE, heir to the powerful Tagge family, Qty : also has his eyes on the prize. Do Aphra and her team stand a chance at fortune and glory? -------- STAR WARS ACTION FIGURE VARIANT Get the ultimate Star Wars action figure collection - in one single, giant-sized comic book! As a child, John Tyler Christopher spent his days playing with COVERS #1 Luke Skywalker, Darth Vader and his beloved Boba Fett. As an adult, $9.99 Christopher has spent the last five years drawing the greatest heroes and villains of the galaxy far, far away in a stellar series of Action Figure Variant Covers to Marvel's Star Wars titles - which have become as sought-after Qty : among fans as the original toys! Now, almost 100 of Christopher's covers - featuring everyone from Ackbar to Zuckuss - are assembled, in all their full- size glory, in this instant collector's item issue. -------- TASKMASTER #1 (OF 5) TASKMASTER HAS MURDERED MARIA HILL! Or at least that's what the whole world thinks. Now the greatest spies in the business are hunting him down $3.99 and won't stop until Taskmaster is dead or clears his own name! Qty : -------- WEB OF VENOM WRAITH #1 Since his appearance in GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY, one thing WRAITH has made perfectly clear is that he's hunting KNULL, the God of the Symbiotes. -

Universidade Federal De Pernambuco Centro De

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA DOUTORADO EM SOCIOLOGIA POR UMA SOCIOLOGIA DA IMAGEM DESENHADA: REPRODUÇÃO, ESTEREÓTIPO E ACTÂNCIA NOS QUADRINHOS DE SUPER-HERÓIS DA MARVEL COMICS. AMARO XAVIER BRAGA JUNIOR RECIFE 2015 AMARO XAVIER BRAGA JUNIOR POR UMA SOCIOLOGIA DA IMAGEM DESENHADA: REPRODUÇÃO, ESTEREÓTIPO E ACTÂNCIA NOS QUADRINHOS DE SUPER- HERÓIS DA MARVEL COMICS. Tese desenvolvida por Amaro Xavier Braga Junior orientada pelo Prof. Dr. Josimar Jorge Ventura de Morais como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Doutor em Sociologia. RECIFE 2015 DEDICATÓRIA Dedico este trabalho aos meus filhos Adrian Céu e Gabriel Sol que toleraram minhas ausências nas brincadeiras e no acompanhamento de suas tarefas de casa e minha pouca disponibilidade para tirar as dúvidas e revisar os assuntos de suas provas, o que impactou bastante suas notas; À minha esposa Danielle, pelas leituras, revisão e comentários, mesmo a contragosto. AGRADECIMENTOS À Universidade Federal de Alagoas pelo programa de Qualificação que me permitiu finalizar a pesquisa nos últimos meses do doutorado; Ao professor Jorge Ventura pela paciência e disposição na orientação; Aos colegas Arthemísia, Lena, Giba, Marcela, Veridiana, Rayane, Regina, Francisco, Márcio, Breno, Glícia, Paula, Caio, Clarissa e Micheline pelos bons momentos e pelas “terapias em grupo” nos momentos de aflição coletiva; Ao professor Henrique Magalhães pela leitura minunciosa e apoio na revisão após a defesa. A Ela, por mais um ciclo. RESUMO A pesquisa analisou o desenvolvimento da actância das histórias em quadrinhos por vias das publicações de HQs de super-herois da editora Marvel Comics, buscando relacionar a reprodução do “social” e a estereotipia como mecanismo performático na figuração agencial. -

The Cadiz Record, Wednesday, July 3, 1991, A-3 3New Members Join DAR’S Thomas Chapter

Your Hometown Newspaper S i n c e 1 8 8 1 T h e Cadiz Record VOL. 110/NO.27 2 SECTIONS WEDNESDAY, JULY 3,1991 CADIZ, KENTUCKY 30 PAGES 50 CENTS Knoth going to Disney World courtesy of Dream Factory This marks third ’dream’ granted by local group By Cindy Camper Epcot Center and MGM Stu will greet the family with a Factory does grant one dream Qt Cadiz Record Editor dios. They will also spend a huge banner saying per terminally ill child. "The day at Sea World with "Welcome Bill." Dream could be a trip, a Five-year-old Bill Knoth Shamu. The family will also be stereo, VCR, computer or never dreamed he would be Since the family i$ the staying at the Holiday Inn whatever," Francis said. leaving for Disney World guests of the Dream Factory, Kid's Village in Orlando "It was a shock for us to find today. But the Cadiz Dream there will be no standing in which is strictly for ill chil out we were going to Disney Factory has arranged for line in the hot, humid Florida dren and their families. World," said Knoth's father, Knoth's family to travel to the sun. Physicians and nurses are Charlie. "Bill said a month is Magic Kingdom for a six-day The family will be issued a on call 24 hours a day at the too long to wait." adventure. special badge that will give village. There also are fam Bill has been a patient at St. Jude's since April of 1988.