A Study of Superhero Mythology Ryan Woods This Is a Digitised Version Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legendary Rules

™ Global Mastermind Abilities Unique Bystanders Each of the 5 new Masterminds in Dark City With Dark City, the Bystander Stack grows has a new feature to make them even more to include three new kinds of Unique powerful: Global Mastermind Abilities. Bystander: the Reporter, the Radiation These abilities spread the Masterminds’ Scientist, and the Paramedic. Players who dark influence continuously, forcing players rescue these Unique Bystanders earn to battle through them. special rewards. The Bystander Stack is now kept face down, shuffled, so you never know New Heroes when you might get a special bonus for Dark City introduces you to 17 new Marvel rescuing a Bystander. Superheroes to recruit and play. New Schemes X-Force: is Cable’s handpicked “Black Dark City includes 8 new Scheme cards to Ops” strike force of superpowered mutants bring even more replayability to the game. that takes on missions too dark for the Some of these Schemes are more intricate X-Men. than before, presenting more dramatic challenges for players to survive. Marvel Knights are a loose group of street-level Heroes that take down Villains through vigilante justice. New Challenge Modes If you want an even greater challenge, you can also try one or more of these ten new Powerful new X-Men increase the optional Challenge Modes. Combining a team roster. Mastermind, a Scheme, and a Challenge “Critical Hit” Superpowers Mode provides an even greater number These potent new Superpower abilities of combinations. Beware: some Challenge show two icons instead of one. You can Modes are crushingly difficult! only use this Superpower ability if you have 1) Gimpy Hand: Each player’s hand size is played cards with both of those icons earlier five cards instead of six. -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

The Avengers (Action) (2012)

1 The Avengers (Action) (2012) Major Characters Captain America/Steve Rogers...............................................................................................Chris Evans Steve Rogers, a shield-wielding soldier from World War II who gained his powers from a military experiment. He has been frozen in Arctic ice since the 1940s, after he stopped a Nazi off-shoot organization named HYDRA from destroying the Allies with a mystical artifact called the Cosmic Cube. Iron Man/Tony Stark.....................................................................................................Robert Downey Jr. Tony Stark, an extravagant billionaire genius who now uses his arms dealing for justice. He created a techno suit while kidnapped by terrorist, which he has further developed and evolved. Thor....................................................................................................................................Chris Hemsworth He is the Nordic god of thunder. His home, Asgard, is found in a parallel universe where only those deemed worthy may pass. He uses his magical hammer, Mjolnir, as his main weapon. The Hulk/Dr. Bruce Banner..................................................................................................Mark Ruffalo A renowned scientist, Dr. Banner became The Hulk when he became exposed to gamma radiation. This causes him to turn into an emerald strongman when he loses his temper. Hawkeye/Clint Barton.........................................................................................................Jeremy -

Ebook Download Incredible Hulk Epic Collection: Ghost of the Past

INCREDIBLE HULK EPIC COLLECTION: GHOST OF THE PAST Author: Peter David,Dale Keown Number of Pages: 480 pages Published Date: 06 Oct 2015 Publisher: Marvel Comics Publication Country: New York, United States Language: English ISBN: 9780785192992 DOWNLOAD: INCREDIBLE HULK EPIC COLLECTION: GHOST OF THE PAST Incredible Hulk Epic Collection: Ghost of the Past PDF Book 1 for Seniors QuickStepsA full-color, visual guide to the basics of Windows 8. Silence in SchoolsSilence is undervalued as a pedagogical tool, yet it is cost-free and educationally significant. Drawing upon the existing evidence-base on academic mentoring in medicine and the health sciences, it applies a case-stimulus learning approach to the common challenges and opportunities in mentorship in academic medicine. - With these words, Lieutenant Commander Robert W. forgottenbooks. Complete Guide to TOEFL Audio Scripts with Answer KeyIt is 1993, and Cedric Jennings is a bright and ferociously determined honor student at Ballou, a high school in one of Washington D. Get started now--the countdown to graduation has already begun. Cognition-Based Assessment and Teaching will help you will all three tiers in RTI. Here Is A Sneak Peak Of What You'll get inside this Password Journal Alphabetical order for you internet passwords and logs A 7x10 sized password journal so it's simple to read Over 100 pages of clearly organized internet password journal pages This is the Easiest internet password journal you will find to write in A Helpful notes section at the bottom of each internet password log Never lose or forget an internet password again with this journal. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

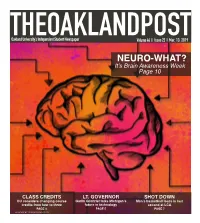

NEURO-WHAT? It’S Brain Awareness Week Page 10

THEOAKLANDPOSTOakland University’s Independent Student Newspaper Volume 44 Issue 22 Mar. 13, 2019 l l NEURO-WHAT? It’s Brain Awareness Week Page 10 CLASS CREDITS LT. GOVERNOR SHOT DOWN OU considers changing course Garlin Gilchrist talks Michigan’s Men’s basketball loses in last credits from four to three future in technology second at LCA PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 7 GRAPHIC BY PRAKHYA CHILUKURI MARCH 13, 2019 | 2 THIS WEEK PHOTO OF THE WEEK THEOAKLANDPOST EDITORIAL BOARD AuJenee Hirsch Laurel Kraus Editor-in-Chief Managing Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 248.370.2537 Elyse Gregory Patrick Sullivan Photo Editor Web Editor [email protected] [email protected] 248.370.4266 EDITORS COPY&VISUAL Katie Valley Campus Editor Mina Fuqua Chief Copy Editor [email protected] Jessica Trudeau Copy Editor Zoe Garden Copy Editor Trevor Tyle Life&Arts Editor Erin O’Neill Graphic Designer [email protected] Prakhya Chilukuri Graphic Assistant Michael Pearce Sports Editor Ryan Pini Photographer [email protected] Nicole Morsfield Photographer Samuel Summers Photographer Jordan Jewell Engagement Editor Sergio Montanez Photographer [email protected] PRIDE MONTH SPEAKER Poet and educator J Mase III opens Pride Month with pow- REPORTERS DISTRIBUTION erful slam poetry about his experiences being black and transgender, and talks about Benjamin Hume Staff Reporter Kat Malokofsky Distribution Director Distributor combating white supremacy and false allyship. PHOTO / NICOLE MORSFIELD Dean Vaglia Staff Reporter Alexander Pham -

Sample Pages to Thor

1 only A Stranger Arrives The air was dry and cold near the small town of Puente Antiguo, New Mexico. Darcy Lewis sat in the driver’s seatReview of an old van full of expensive scientic equipment. She was a college student working with scientist Jane Foster. Another scientist, ForDr. Erik Selvig, sat in the passenger seat. In the back of the van, Jane- opened the roof and climbed onto it. Selvig followed her, and they looked up into the darkness. “So what exactly are we looking for?” Selvig asked. He was a friend of Jane’s father and knew her well. “Why did you ask me to join you here in New Mexico?” “I told youSample. Something strange is happening in the night sky and I need your help,” Jane replied. “It’s a little dierent each time. Once it was a pool of stars in a corner of the sky. But last week it was a rainbow—” A noise from her computer stopped her. “Wait for it!” she said excitedly. Nothing happened. The sky above them stayed calm and black. Darcy put her head out of the window and looked up at Jane. “Can I turn on the radio?” she asked. She sounded bored. “No!” Jane replied angrily. She and Selvig climbed back inside the van. “I don’t understand,” she said. She opened a small book and looked at her notes. She always carried this notebook—inside it was her life’s work. M01_THOR_SB3_GLB_05991.indd 1 3/6/18 1:53 PM 2 “These changes have happened many times, always at night, Erik!” She checked her computer. -

CA Students Urge Assembly Members to Pass AB

May 26, 2021 The Honorable Members of the California State Assembly State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Thousands of CA Public School Students Strongly Urge Support for AB 101 Dear Members of the Assembly, We are a coalition of California high school and college students known as Teach Our History California. Made up of the youth organizations Diversify Our Narrative and GENup, we represent 10,000 youth leaders from across the State fighting for change. Our mission is to ensure that students across California high schools have meaningful opportunities to engage with the vast, diverse, and rich histories of people of color; and thus, we are in deep support of AB101 which will require high schools to provide ethnic studies starting in academic year 2025-26 and students to take at least one semester of an A-G approved ethnic studies course to graduate starting in 2029-30. Our original petition made in support of AB331, linked here, was signed by over 26,000 CA students and adult allies in support of passing Ethnic Studies. Please see appended to this letter our letter in support of AB331, which lists the names of all our original petition supporters. We know AB101 has the capacity to have an immense positive impact on student education, but also on student lives as a whole. For many students, our communities continue to be systematically excluded from narratives presented to us in our classrooms. By passing AB101, we can change the precedent of exclusion and allow millions of students to learn the histories of their peoples. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Resistant Vulnerability in the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-15-2019 1:00 PM Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America Kristen Allison The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Susan Knabe The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Media Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Kristen Allison 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Allison, Kristen, "Resistant Vulnerability in The Marvel Cinematic Universe's Captain America" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6086. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6086 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Established in 2008 with the release of Iron Man, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has become a ubiquitous transmedia sensation. Its uniquely interwoven narrative provides auspicious grounds for scholarly consideration. The franchise conscientiously presents larger-than-life superheroes as complex and incredibly emotional individuals who form profound interpersonal relationships with one another. This thesis explores Sarah Hagelin’s concept of resistant vulnerability, which she defines as a “shared human experience,” as it manifests in the substantial relationships that Steve Rogers (Captain America) cultivates throughout the Captain America narrative (11). This project focuses on Steve’s relationships with the following characters: Agent Peggy Carter, Natasha Romanoff (Black Widow), and Bucky Barnes (The Winter Soldier). -

Constructing Daddy: the Absent Father, Revisionist Masculinity And/In Queer Cultural Representations

disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory Volume 9 manholes Article 3 4-15-2000 (De)Constructing Daddy: The Absent Father, Revisionist Masculinity and/in Queer Cultural Representations Andrew Schopp University of Tennessee Martin DOI: https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.09.03 Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure Part of the English Language and Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Schopp, Andrew (2000) "(De)Constructing Daddy: The Absent Father, Revisionist Masculinity and/in Queer Cultural Representations," disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory: Vol. 9 , Article 3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13023/disclosure.09.03 Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/disclosure/vol9/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by disClosure: A Journal of Social Theory. Questions about the journal can be sent to [email protected] Andrew Schopp (De )Constructing Daddy: The Absent Father, Revisionist Masculinity and/in Queer Cul tural Representations Contemporary cultur i almo l ob e eel with a11 Ab ent Fath r mythology. Whether literal or metaphoric, th Ab e 11l Fath r fi gure in nu merou cultural repr enlalion and ha b n po it d a th e ~ oure of v rything from problem ati c mal e beha vior lo male anxieti es about what it m an to b ma culine. Ilow v r, th e Ab enl Fath r i. an especially troubling fi gu r for gay men. I I t ronormal i ve approach to xuali Ly and p yc hologi ·al developm n t, from Freud 1 lo Jung2 Lo ronl mporary religiou ri ght mini tri that would ''cure" queers/1 have con tructed and maintain cl a cultural paradigm in whi ch th e ho mo xual mal e (mo l oft n een a a male who fail al ma culinit.