Cedar Waxwings in Central Alaska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Bird Highlights 2013

FROM PROJECT FEEDERWAtch 2012–13 Focus on citizen science • Volume 9 Winter BirdHighlights Winter npredictability is one constant as each winter Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- brings surprises to our feeders. The 2012–13 sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2013, is brought to you by Project FeederWatch, a research and education proj- season broke many regional records with sis- ect of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies U Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the kins and nuthatches moving south in record numbers efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. to tantalize FeederWatchers across much of the con- Project FeederWatch Staff tinent. This remarkable year also brought a record- David Bonter breaking number of FeederWatchers, with more than Project Leader, USA Janis Dickinson 20,000 participants in the US and Canada combined! Director of Citizen Science, USA Kristine Dobney Whether you’ve been FeederWatching for 26 years or Project Assistant, Canada Wesley Hochachka this is your first season counting, the usual suspects— Senior Research Associate, USA chickadees, juncos, and woodpeckers—always bring Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant, USA familiarity and enjoyment, as well as valuable data, Rosie Kirton Project Support, Canada even if you don’t observe anything unusual. Whichever Denis Lepage birds arrive at your feeder, we hope they will bring a Senior Scientist, Canada Susan E. Newman sense of wonder that captures your attention. Thanks Project Assistant, USA for sharing your observations and insights with us and, Kerrie Wilcox Project Leader, Canada most importantly, Happy FeederWatching. -

A Birder's Guide to Cook County, Northeastern Minnesota Birding

A Birder’s Guide to Cook County, Northeastern Minnesota This guide will help you find the birds of Cook County, one of the best birding areas in the upper midwest. The shore of Lake Superior and the wildlands of the northeast are natural treasures that are especially rich in birds. Descriptions of the locatoins can be found inside, along with information about how to make the most of your birding during each season of the year. Birding around the year Spring: The migration is always most exciting along the shore of Lake Superior. Spring migration is smaller than fall, but spring specialties include Tundra Swan, Sandhill Crane, Gray-cheeked Thrush, American Tree Sparrow, Harris’ Sparrow, Lapland Longspur and Rusty Blackbird. Boreal species like Black-backed Woodpecker, Boreal Owl and Northern Saw-whet Owl begin nesting during spring, which can begin as early as March and extend until June. Summer: In summer the excitement moves inland where specialties inclue Common Loon, American Black Duck, Bald Eagle, Ruffled Grouse, American Woodcock, Black-billed Cuckoo, Barred Owl, Northern Saw- whet Owl, Whip-poor-will, Olive-sided, Yellow-bellied, and Alder Flycatchers, Gray Jay, Boreal Chickadee, Winter and Sedge Wrens, 20 species of warblers, Le Conte’s Sparrow, and Evening Grosbeak. The summer breeding season extends from late May through early August. Autumn: the fall migration along the Norht Shore of Lake Superior is not to be missed! Beginning with the sight of thousands of Common Nighthawks in late August, the sheer quantity of birds moving down the shore makes this area a world-class migration route. -

Summary Data

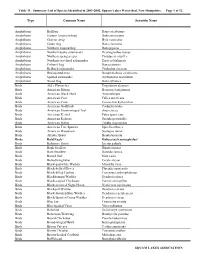

Table 11. Summary List of Species Identified in 2001-2002, Squam Lakes Watershed, New Hampshire. Page 1 of 12 Type Common Name Scientific Name Amphibians Bullfrog Rana catesbeiana Amphibians Eastern American toad Bufo americanus Amphibians Gray treefrog Hyla versicolor Amphibians Green frog Rana clamitans Amphibians Northern leopard frog Rana pipiens Amphibians Northern dusky salamander Desmognathus fuscus Amphibians Northern spring peeper Pseudacris crucifer Amphibians Northern two-lined salamander Eurycea bislineata Amphibians Pickerel frog Rana palustris Amphibians Redback salamander Plethodon cinereus Amphibians Red-spotted newt Notophthalmus viridescens Amphibians Spotted salamander Ambystoma maculatum Amphibians Wood frog Rana sylvatica Birds Alder Flycatcher Empidonax alnorum Birds American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Birds American Black Duck Anas rubripes Birds American Coot Fulica americana Birds American Crow Corvus brachyrhynchos Birds American Goldfinch Carduelis tristis Birds American Green-winged Teal Anas crecca Birds American Kestrel Falco sparverius Birds American Redstart Setophaga ruticilla Birds American Robin Turdus migratorius Birds American Tree Sparrow Spizella arborea Birds American Woodcock Scolopax minor Birds Atlantic Brant Branta bernicla Birds Bald Eagle* Haliaeetus leucocephalus* Birds Baltimore Oriole Icterus galbula Birds Bank Swallow Riparia riparia Birds Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica Birds Barred Owl Strix varia Birds Belted Kingfisher Ceryle alcyon Birds Black-and-white Warbler Mniotilta varia Birds -

Winter Bird Highlights 2015, Is Brought to You by U.S

Winter Bird Highlights FROM PROJECT FEEDERWATCH 2014–15 FOCUS ON CITIZEN SCIENCE • VOLUME 11 Focus on Citizen Science is a publication highlight- FeederWatch welcomes new ing the contributions of citizen scientists. This is- sue, Winter Bird Highlights 2015, is brought to you by U.S. project assistant Project FeederWatch, a research and education proj- ect of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Project FeederWatch is made possible by the e are pleased to have a new efforts and support of thousands of citizen scientists. Wteam member on board! Meet Chelsea Benson, a new as- Project FeederWatch Staff sistant for Project FeederWatch. Chelsea will also be assisting with Cornell Lab of Ornithology NestWatch, another Cornell Lab Janis Dickinson citizen-science project. She will Director of Citizen Science be responding to your emails and Emma Greig phone calls and helping to keep Project Leader and Editor the website and social media pages Anne Marie Johnson Project Assistant up-to-date. Chelsea comes to us with a back- Chelsea Benson Project Assistant ground in environmental educa- Wesley Hochachka tion and conservation. She has worked with schools, community Senior Research Associate organizations, and local governments in her previous positions. Diane Tessaglia-Hymes She incorporated citizen science into her programming and into Design Director regional events like Day in the Life of the Hudson River. Chelsea holds a dual B.A. in psychology and English from Bird Studies Canada Allegheny College and an M.A. in Social Science, Environment Kerrie Wilcox and Community, from Humboldt State University. Project Leader We are excited that Chelsea has brought her energy and en- Rosie Kirton thusiasm to the Cornell Lab, where she will no doubt mobilize Project Support even more people to monitor bird feeders (and bird nests) for Kristine Dobney Project Assistant science. -

Birds of Anchorage Checklist

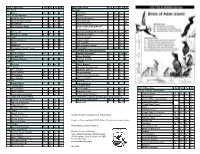

ACCIDENTAL, CASUAL, UNSUBSTANTIATED KEY THRUSHES J F M A M J J A S O N D n Casual: Occasionally seen, but not every year Northern Wheatear N n Accidental: Only one or two ever seen here Townsend’s Solitaire N X Unsubstantiated: no photographic or sample evidence to support sighting Gray-cheeked Thrush N W Listed on the Audubon Alaska WatchList of declining or threatened species Birds of Swainson’s Thrush N Hermit Thrush N Spring: March 16–May 31, Summer: June 1–July 31, American Robin N Fall: August 1–November 30, Winter: December 1–March 15 Anchorage, Alaska Varied Thrush N W STARLINGS SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER SPECIES SPECIES SPRING SUMMER FALL WINTER European Starling N CHECKLIST Ross's Goose Vaux's Swift PIPITS Emperor Goose W Anna's Hummingbird The Anchorage area offers a surprising American Pipit N Cinnamon Teal Costa's Hummingbird Tufted Duck Red-breasted Sapsucker WAXWINGS diversity of habitat from tidal mudflats along Steller's Eider W Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Bohemian Waxwing N Common Eider W Willow Flycatcher the coast to alpine habitat in the Chugach BUNTINGS Ruddy Duck Least Flycatcher John Schoen Lapland Longspur Pied-billed Grebe Hammond's Flycatcher Mountains bordering the city. Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel Eastern Kingbird BOHEMIAN WAXWING Snow Bunting N Leach's Storm-Petrel Western Kingbird WARBLERS Pelagic Cormorant Brown Shrike Red-faced Cormorant W Cassin's Vireo Northern Waterthrush N For more information on Alaska bird festivals Orange-crowned Warbler N Great Egret Warbling Vireo Swainson's Hawk Red-eyed Vireo and birding maps for Anchorage, Fairbanks, Yellow Warbler N American Coot Purple Martin and Kodiak, contact Audubon Alaska at Blackpoll Warbler N W Sora Pacific Wren www.AudubonAlaska.org or 907-276-7034. -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

The Birds of New York State

__ Common Goldeneye RAILS, GALLINULES, __ Baird's Sandpiper __ Black-tailed Gull __ Black-capped Petrel Birds of __ Barrow's Goldeneye AND COOTS __ Little Stint __ Common Gull __ Fea's Petrel __ Smew __ Least Sandpiper __ Short-billed Gull __ Cory's Shearwater New York State __ Clapper Rail __ Hooded Merganser __ White-rumped __ Ring-billed Gull __ Sooty Shearwater __ King Rail © New York State __ Common Merganser __ Virginia Rail Sandpiper __ Western Gull __ Great Shearwater Ornithological __ Red-breasted __ Corn Crake __ Buff-breasted Sandpiper __ California Gull __ Manx Shearwater Association Merganser __ Sora __ Pectoral Sandpiper __ Herring Gull __ Audubon's Shearwater Ruddy Duck __ Semipalmated __ __ Iceland Gull __ Common Gallinule STORKS Sandpiper www.nybirds.org GALLINACEOUS BIRDS __ American Coot __ Lesser Black-backed __ Wood Stork __ Northern Bobwhite __ Purple Gallinule __ Western Sandpiper Gull FRIGATEBIRDS DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS __ Wild Turkey __ Azure Gallinule __ Short-billed Dowitcher __ Slaty-backed Gull __ Magnificent Frigatebird __ Long-billed Dowitcher __ Glaucous Gull __ Black-bellied Whistling- __ Ruffed Grouse __ Yellow Rail BOOBIES AND GANNETS __ American Woodcock Duck __ Spruce Grouse __ Black Rail __ Great Black-backed Gull __ Brown Booby __ Wilson's Snipe __ Fulvous Whistling-Duck __ Willow Ptarmigan CRANES __ Sooty Tern __ Northern Gannet __ Greater Prairie-Chicken __ Spotted Sandpiper __ Bridled Tern __ Snow Goose __ Sandhill Crane ANHINGAS __ Solitary Sandpiper __ Least Tern __ Ross’s Goose __ Gray Partridge -

Persistence of Host Defence Behaviour in the Absence of Avian Brood

Downloaded from http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on February 12, 2015 Biol. Lett. (2011) 7, 670–673 selection is renewed, and therefore may accelerate an doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0268 evolutionary response to the selection pressure. Published online 14 April 2011 We examined the extent to which a behavioural Animal behaviour defence persists in the absence of selection from avian brood parasitism. The interactions between avian brood parasites and their hosts are ideal for Persistence of host determining the fate of adaptations once selection has been relaxed, owing to shifting distributions of defence behaviour in the hosts and parasites [5,6] or the avoidance of well- defended hosts by parasites [7,8]. Host defences such absence of avian brood as rejection of parasite eggs may be lost in the absence parasitism of selection if birds reject their oddly coloured eggs [9,10], but are more likely to be retained because Brian D. Peer1,2,3,*, Michael J. Kuehn2,4, these behaviours may never be expressed in circum- Stephen I. Rothstein2 and Robert C. Fleischer1 stances other than parasitism [2,3]. Whether host 1Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, defences persist in the absence of brood parasitism is Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, critical to long-term avian brood parasite–host coevolu- Smithsonian Institution, PO Box 37012, MRC 5503, Washington, tion. If defences decline quickly, brood parasites can DC 20013-7012, USA alternate between well-defended hosts and former 2Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA hosts that have lost most of their defences, owing to the 3Department of Biological Sciences, Western Illinois University, Macomb, costs of maintaining them once parasitism has ceased, IL 61455, USA 4 or follow what has been termed the ‘coevolutionary Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology, 439 Calle San Pablo, cycles’ model of host–brood parasite coevolution [3]. -

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I -

Inner Mongolia Cumulative Bird List Column A

China: Inner Mongolia Cumulative Bird List Column A: total number of days that the species was recorded in 2016 Column B: maximum daily count for that particular species Column C: H = Heard only; (H) = Heard more often than seen Globally threatened species as defined by BirdLife International (2004) Threatened birds of the world 2004 CD-Rom Cambridge, U.K. BirdLife International are identified as follows: EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; NT = Near- threatened. A B C Ruddy Shelduck 2 3 Tadorna ferruginea Mandarin Duck 1 10 Aix galericulata Gadwall 2 12 Anas strepera Falcated Teal 1 4 Anas falcata Eurasian Wigeon 1 2 Anas penelope Mallard 5 40 Anas platyrhynchos Eastern Spot-billed Duck 3 12 Anas zonorhyncha Eurasian Teal 2 12 Anas crecca Baer's Pochard EN 1 4 Aythya baeri Ferruginous Pochard NT 3 49 Aythya nyroca Tufted Duck 1 1 Aythya fuligula Common Goldeneye 2 7 Bucephala clangula Hazel Grouse 4 14 Tetrastes bonasia Daurian Partridge 1 5 Perdix dauurica Brown Eared Pheasant VU 2 15 Crossoptilon mantchuricum Common Pheasant 8 10 Phasianus colchicus Little Grebe 4 60 Tachybaptus ruficollis Great Crested Grebe 3 15 Podiceps cristatus Eurasian Bittern 3 1 Botaurus stellaris Yellow Bittern 1 1 H Ixobrychus sinensis Black-crowned Night Heron 3 2 Nycticorax nycticorax Chinese Pond Heron 1 1 Ardeola bacchus Grey Heron 3 5 Ardea cinerea Great Egret 1 1 Ardea alba Little Egret 2 8 Egretta garzetta Great Cormorant 1 20 Phalacrocorax carbo Western Osprey 2 1 Pandion haliaetus Black-winged Kite 2 1 Elanus caeruleus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. -

Advances in the Study of Irruptive Migration

Advances in the study of irruptive migration Ian Newton1 Newton I. 2006. Advances in the study of irruptive migration. Ardea 94(3): 433–460. This paper discusses the movement patterns of two groups of birds which are generally regarded as irruptive migrants, namely (a) boreal finches and others that depend on fluctuating tree-fruit crops, and (b) owls and others that depend on cyclically fluctuating rodent popula- tions. Both groups specialise on food supplies which, in particular regions, fluctuate more than 100-fold from year to year. However, seed- crops in widely separated regions may fluctuate independently of one another, as may rodent populations, so that poor food supplies in one region may coincide with good supplies in another. If individuals are to have access to rich food supplies every year, they must often move hun- dreds or thousands of kilometres from one breeding area to another. In years of widespread food shortage (or high numbers relative to food supplies) extending over many thousands or millions of square kilome- tres, large numbers of individuals migrate to lower latitudes, as an ‘irruptive migration’. For these reasons, the distribution of the popula- tion, in both summer and winter, varies greatly from year to year. In irruptive migrants, in contrast to regular migrants, site fidelity is poor, and few individuals return to the same breeding areas in succes- sive years (apart from owls in the increase phase of the cycle). Moreover, ring recoveries and radio-tracking confirm that the same indi- viduals can breed in different years in areas separated by hundreds or thousands of kilometres. -

Get Our Falsterbo Bird Species Checklist Here!

Diving Ducks (cont.) Cormorants Birds of Prey (cont.) Greater Scaup Great Cormorant Common Kestrel Bird Species List Common Eider Herons, Storks, Ibises Red-Footed Falcon King Eider Great Bittern Merlin Falsterbo, Sweden Steller's Eider Little Egret Eurasian Hobby Long-Tailed Duck Great Egret Eleonora'S Falcon Swans Common Scoter Grey Heron Gyr Falcon Mute Swan Velvet Scoter Purple Heron Peregrine Falcon Tundra Swan Common Goldeneye Black Stork Rails & Crakes Whooper Swan Sawbills White Stork Water Rail Geese Smew Glossy Ibis Spotted Crake Bean Goose Red-Breasted Merganser Eurasian Spoonbill Corn Crake Pink-Footed Goose Goosander Birds of Prey Common Moorhen Greater White-Fronted Goose Partridges & Pheasants European Honey Buzzard Common Coot Lesser White-Fronted Goose Grey Partridge Black-Winged Kite Cranes Greylag Goose Common Quail Black Kite Common Crane Canada Goose Common Pheasant Red Kite Demoiselle Crane Barnacle Goose Loons (Divers) White-Tailed Eagle Bustards Brent Goose Red-Throated Diver Egyptian Vulture Great Bustard Red-Breasted Goose Black-Throated Diver Eurasian Griffon Vulture Waders Egyptian Goose Great Northern Diver Short-Toed Eagle Eurasian Oystercatcher Dabbling Ducks Yellow-Billed Diver Western Marsh Harrier Black-Winged Stilt Ruddy Shelduck Grebes Hen Harrier Pied Avocet Common Shelduck Little Grebe Pallid Harrier Stone-Curlew Eurasian Wigeon Great Crested Grebe Montagu's Harrier Collared Pratincole American Wigeon Red-Necked Grebe Northern Goshawk Oriental Pratincole Gadwall Slavonian Grebe Eurasian Sparrowhawk