Storytelling with UK Centenarians: Being a Hundred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daytoday Catering Web-1.Pdf

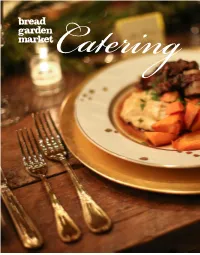

bread garden market Catering breakfast savory breakfast bagel platter signature bread scrambled eggs, bacon or Bread 15 assorted bagels with 2oz pudding Garden Market sausage, croissant portions of cream cheese: plain, $35.00 pan [serves 10] french toast, and herbed potatoes veggie or strawberry $7.99 person $25 *minimum order of 10 servings *add lox and garnishes for croissant french toast $5 person $35.00 pan [serves 10] homemade quiche assorted quiche baked in our pastry platter scratch made scones flaky pie crust. choose from 20 pieces of assorted mini blueberry, chocolate, or margherita quiche lorraine, five cheese, pastries: muffins, croissants, $2.99 each or vegetable danish, and cinnamon rolls full size $18 (serves 6) $25 butter croissant personal size $2.99 each fresh baked muffins $2.99 each bgm scramble zucchini, blueberry, banana $9.99 dozen half size egg scramble with ham, peppers, chocolate chip, pumpkin pecan, caramelized onion, and lemon raspberry, or lemon pepper jack cheese $1.99 each filled croissant with a side of herbed potatoes $11.99 dozen for half-size chocolate, almond, or ham and swiss $6.99 person $3.49 each $21.99 dozen half size BG doughnuts pecan sticky buns egg casserole classic glazed doughnuts $2.99 each egg bake with potatoes, made from scratch bacon or house made sausage, $.99 each danish and cheese $10.99 dozen $6.99 person Assorted fruit or cheese fillings *minimum order of 5 dozen $2.49 each *minimum order of 10 servings Monday-Thursdays sweet breads A la carte sides breakfast burrito pumpkin, apple -

Bakery Packet

Bakery Packet Linn Benton Culinary Arts B A K E R Y Each student must be able to show competence in the following areas in order to successfully complete this course of instruction. Understand and Demonstrate: 1. The different mixing methods of breads and rolls, cakes and cookies, short dough’s. 2. Rolled-in doughs (Danish, Puff Pastry, Croissant, ect.) 3. Custard cookery (Creme Brulee, Pastry Cream, ect.) 4. Pate a choux (Cream puffs, Eclairs) 5. Basic cake decorating techniques Each student will rotate during the term to each of the following stations: 1. Bread 2. Laminated Pastry Doughs 3. Cakes 4. Short dough/Gluten Free Dietary Needs 5. Custards 6. Rounds The amount of total time in each station will vary by the number of weeks per term. On average, 1 to 1 ½ weeks per station each term. Students must execute the daily production in an efficient manner making sure to have bread and desserts ready for lunch service, 11:00 a.m. Santiam Restaurant; and 10:30 to Cafeteria. Students are responsible for cleaning the Bakery on a daily basis. They are also responsible for minimizing waste by finding uses for leftovers and products found in the walk-in and reach-in. BAKERY CLEAN-UP Will be expected to go through daily cleaning requirements to ensure quality of our establishment and sanitary conditions of the bakery. ROUNDS STATION The student in this station will be required to perform the following duties: 1. Inventory products, ingredients and already prepared desserts available for that day’s service. 2. Draft that day’s menu under the supervision of the lab instructor and post that day’s production schedule as well as the remainder of the labs during the week. -

Westside Seattle 7-7-17

FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 27 Westside Seattle Your neighborhood weekly serving Ballard, Burien/Highline, SeaTac, Des Moines, West Seattle and White Center SUMMER IS FINALLY HERE GET OUTSIDE!See West Seattle Summer Fest Schedule » P. 11 Photo by Kimberly Robinson Photos by Patrick Robinson See our listings on page 14 4700 42nd S.W. • 206-932-4500 • BHHSNWRealEstate.com © 2017 HSF Aliates LLC. 2 FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 WESTSIDE SEATTLE FRIDAY, JULY 7, 2017 | Vol. 99, No. 27 Borderlines (revisited) Editor’s note: Here is an offering by last Saturday and quoth, “The kids have and on arriving he organized us into a Lee Robinson, who my four brothers and I been bugging me to take them fishing work crew. While we were spreading called Mom, from one of her periodic col- Sunday and I don’t really want to go my- out camp in a lovely gravel pit, he dis- umns. This one from Aug. 15, 1962. There self but you know how it is. They’re little appeared, as was to be expected. But was a family rumor that Mom often wrote for such a short time.” we didn’t mind, we had food, the sun Ballard News-Tribune, Highline Times, West Seattle Herald, Dad’s weekly column, Borderlines, after he We have heard this blarney so often we was shining, the river rippled peaceful- Des Moines News, SeaTac News, White Center News fell asleep in the chair when he had typed a just went about our duties and said noth- ly and all was right with the world for single word, then groggily schlepped off to ing. -

Blaze Damages Ceramic Building

• ev1e Voi.106No.59 University of Delaware, Newqrk. DE Financial aid expecte to be awarded in July By BARBARA ROWLAND To deal with the budgetary The Office of Financial Aid impasse, the university's is anticipating a "bottleneck" financial aid office will send in processing Guaranteed out estimated and unofficial Student Loans (GSLs) as soon award notices on the basis as the federal budget is pass- that the prog19ms will re- ed by-Congr.ess. main the same'-- Because Lhe==amount-oL __- M_ac!)_o_!!ald does 11:0t expect federal funding for both Pell to receive an indication on the Grants and the GSL program amount of. f~ding for Pell has not yet been determined Grants untll this July. the university has not bee~ In an effort to alleviate the - able to award financial aid pressure students may feel packages, according to Direc- -about tuition payments, Mac tor of Financial Aid Douglas Donald said the university MacDonald. will allow students to pay their tuition a quarter at a MacDonald emphasized the time, instead of a half and problem of funding student half installment plan. assistance is not as serious as The university has the problem with delivering also established a $50,000 aid in time for the fall scholarship progr.ani to semester. award students on the basis of MacDonald believes it is both merit and need. unlikely Congress will imple Some of tne changes the ment any changes in the two financial aid office has pro , . _ . Review Photo by Leigh Clifton programs in 1982-83 because jected for next year include: FIREMEN' RESPOND TO A BLAZE at the university's cer'amic building Wednesday night which of the late date. -

ABL Wholesale Product Catalogue Draft V6.Indd

Pandoro Bakery Products We are a New Zealand family owned bakery committed to being world-class. Take a look at our range and become a part of our success story. One Company Two Brands One Call Centre One Delivery One Invoice Our Range: Page Page Artisan Stone Baked Breads 1 Pastries & Danish 8 Artisan Tin Breads 1 Croissants 8 Artisan Mini Tin Loaf 1 Doughnuts & Cronut 8 Block Toast Sliced 1 Eclair 8 Artisan Flat Breads 2 Sweet Brioche 8 Auckland Bakeries Panini 2 Muffins 9 Turkish 2 Cupcakes 9 Baguettes 2 Cakes - Individual 9 Artisan Buns & Rolls 3 Tarts & Tartlets 10 Round Flats 4 Fresh Cream Slices 10 Dinner Rolls 4 Lamingtons 11 Baps 4 Fresh Cream Gateaux 11 Long Rolls 4 Fresh Cream Log 11 Bagels 5 Cheesecakes 11 Hot Cakes 5 Sweet Pies 12 English Toasting Muffins 5 Biscuits 12 Scones 5 Cookies 12 Small Savouries 5 Biscotti 12 Pies 6 Slices 13 Pies - Wrapped 6 Cakes & Desserts 13 Quiche 7 Cake Slabs - Half or Full 14 Ordering Information All orders must be received by 3pm day prior No deliveries on Sunday Minimum $30 +GST Two day order for all sourdough products How To Place An Order Email [email protected] Phone 09 588 5000 0800 PANDORO www.pandoro.co.nz Artisan Stone Baked Ciabatta Italian Loaf Frumento Normandy Rye Large, Small Large, Regular Large, Regular San Francisco Sourdough Vienna Sourdough Boule Artisan Tin Breads Brioche Five Grain Sourdough Pain de Mie Plain Loaf with Large, Regular Sesame Seeds San Francisco Sourdough Wholemeal Walnut Artisan Mini Tin Loaf Block Toast Sliced Five Grain Sourdough Multigrain White Pandoro -

Supercentenarians Landscape Overview

Supercentenarians Landscape Overview Top-100 Living Top-100 Longest-Lived Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active Executive and Infographic Summary GERONTOLOGY RESEARCH GROUP www.aginganalytics.com www.grg.org Supercentenarians Landscape Overview Foreword 3 Top-100 Living Supercentenarians Overview 44 Preface. How Long Can Humans Live and 4 Ages of Oldest Living Supercentenarians by Country 46 the Importance of Age Validation Top-100 Living Supercentenarians Continental Executive Summary 10 47 Distribution by Gender Introduction. 26 Top-100 Living Supercentenarians Distribution by Age 50 All Validated Supercentenarians Сhapter III. Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active All Supercentenarians Region Distribution by Gender 29 52 Living Centenarians Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active Centenarians All Supercentenarians Distribution by Nations 30 53 Overview Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active Centenarians Longest-Lived Supercentenarians Distribution by Country 31 54 Distribution by Nation Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active Centenarians All Supercentenarians Distribution by Gender and Age 32 55 Gender Distribution Top-25 Socially and Professionally Active Centenarians Сhapter I. Top-100 Longest-Lived Supercentenarians 35 56 Distribution by Type of Activity Chapter IV. Profiles of Top-100 Longest-Lived Top-100 Longest-Lived Supercentenarians Overview 36 57 Supercentenarians Top-100 Longest-Lived Supercentenarians Regional 38 Chapter V. Profiles of Top-100 Living Supercentenarians 158 Distribution by Gender Top-100 Longest-Lived Supercentenarians Distribution by Chapter VI. Profiles of Top-25 Socially and Professionally 40 259 Age Active Living Centenarians and Nonagenarians Сhapter II. Top-100 Living Supercentenarians 43 Disclaimer 285 Executive Summary There have always been human beings who have lived well beyond normal life expectancy, these ‘supercentenarians’ who lived past 110 years of age. -

Baking Problems Solved Related Titles

Baking Problems Solved Related Titles Steamed Breads: Ingredients, Processing and Quality (ISBN: 978-0-08-100715-0) Cereal Grains, 2e (ISBN: 978-0-08-100719-8) Cereal Grains for the Food and Beverage Industries (ISBN: 978-0-85709-413-1) Baking Problems Solved Second Edition Stanley P. Cauvain Woodhead Publishing is an imprint of Elsevier The Officers’ Mess Business Centre, Royston Road, Duxford, CB22 4QH, United Kingdom 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, OX5 1GB, United Kingdom Copyright r 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility. -

Their Ancestors Signed the Mayflower Compact Heller Helps Political

SERVING CRANFORD, QARWOOD and KENILWORTH Vol. 94 No. 47 Published Every Thursday Wednesday, November 25, 1987 USPS 136 800 Second Class Postage Paid Cranford, N. J. 30 CENTS y?~''i Service tonight >ffS& The annual community | Thanksgiving service win take, place at 8 p m. today at the Trlni-' ty Episcopal Church, North and | Forest avenues. Clergy from, Cranford congregations will par- \ ticipato in the service. Tree lighting A traditional tree lighting | mv. ceremony will take place Friday j at 7 p.m. at the town Christmas tree hi the parking lot opposite | the municipal building. Santa will i greet children and Us helpers1 will distribute treats, the madrigal singers and brass] ensemble from Cranford High] School will perform. Garwood A Garwood beekeeper has quite a collection: 180,000 honey pit* Santa's first visit to town: C ^-^I,a>icaggy.^-^,^ZI::.' ••^..: •--^- —a roll students were announced for, c *• - ,i t« />i . r. * I1J,ws-on-de8lrod-gl+ts-to--perform^WiTrte^VVoTTrierland MedreT cording to police esTimalesT the first marking period. Page 19. -Sa^^nd-M^laus^t-Mangea oi mor Sun d a r Building event sponsored by-uajTExTravagaliza '87 Stage Show Sunday. Mayor's Park capped event. More photographs 25 ^ #™£ c? ? ?^ / , y- and received candy canes In show- In ffrehouse parking lot followed SS1 ui m? . a"d Mrs. Claus played by fernle Ragucci and musical parade and child visits with Santa that on pages 13, 18 and 21. Photo by Greg Price. Donate food Dot Mikus. Photo by Greg Price. Cranford Family Care is pro-] viding food baskets to less for- tunate residents for Thanksgiv- Their ancestors signed the Mayflower Compact ing. -

Died On: April 15, 2017 Place of Death: Verbania FAMOUS AS: SUPERCENTENARIAN

Carlo won the German Cuisine in a box. Thank you to Lynn & Dottie for donating. THANK YOU LODGE SISTER ROSE FOR THE GREAT PHOTOS Learning the Tarentella, Anne There was a Comedian to Entertain us. HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO LODGE SISTERS & BROTHERS CELEBRATING IN NOVEMBER Buon compleanno per alloggiare sorelle & fratelli che festeggiano nel Novembre Simonetta Stefanelli November 30, 1954 ROME, ITALY Simonetta Stefanelli is an Italian actress, entrepreneur and fashion designer. Internationally, she is best known for her performance as Apollonia Vitelli-Corleone in the 1972 film The Godfather, directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Her other roles include appearances in Moses the Lawgiver, Scandal in the Family and Three Brothers. In 1992, Stefanelli made her last film appearance in the drama Le amiche del cuore directed by her then husband Michele Placido. AN ITALIAN ACTRESS BORN IN ROME, SIMONETTA STEFANELLI MADE HER FIRST APPEARENCE IN LA MOGLIE GIAPPONESE AND APPEARED IN SEVERAL ITALIAN FILMS BEFORE APPEARING IN HER FIRST INTERNATIONAL ROLE IN THE GODFATHER, AS APOLLONIA, AT THE AGE OF 16. Simonetta Stefanelli was born on November 30, 1954, in Rome, Lazio, Italy. She started acting in Italian movies as a child artist and was about 16 years old when she was offered the role of ‘Apollonia Vitelli– Corleone’ in the movie ‘The Godfather.’ After her performance in ‘The Godfather,’ she received numerous offers from Hollywood which she turned down, as she feared being stereotyped as a sex symbol. She preferred to continue with her career in Italy and appeared in a number of TV serials and movies, such as ‘The King is the Best Mayor,’ ‘The Big Family,’ and ‘Moses the Lawgiver. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

NEBRASKA's CENTENARIANS AGE 107 OR ABOVE — 1867 to 2001

NEBRASKA’S CENTENARIANS AGE 107 OR ABOVE — 1867 to 2001 by E. A. Kral May 1, 2014 update of original published in The Crete News, April 24, 2002, a 40-page supplement Public Announcement for All Nebraskans Effective May 1, 2002, the Nebraska Health Care Association initiated two on-going public service projects on its website to highlight Nebraskans who reach age 107 or above. The NHCA website address is www.nehca.org. First, the NHCA has maintained a roster of living Nebraskans who have attained the age of 107 or above that provides name, birth date, and county in which the person resides. Second, the NHCA has made available access to this updated manuscript version of E. A. Kral’s “Nebraska’s Centenarians Age 107 or Above — 1867 to 2001” but without photographs. Moreover, it has also offered a brief on-going ranking of Nebraska’s supercentenarians in state history, and another document titled “Oldest Twins in Nebraska History.” Relatives, healthcare professionals, and others are asked to notify the NHCA when someone with Nebraska connections reaches age 107 for placement of name, birth date, and county of residence on the living roster. Since age verification may be necessary via census records involving the centenarian’s youth or early adult years, relatives may assist by providing names of parents and location of centenarian during 1900 to 1920. Also please notify the NHCA when the persons on the living roster become deceased so that the roster may be current. The NHCA website address is www.nehca.org and referrals for the living 107-year-old roster may be mailed to Nebraska Health Care Association, 1200 Libra Dr., Ste 100, Lincoln, NE 68512-9332. -

Searching for the Secrets of the Super Old More and More People Are Living Past 110

NEWSFOCUS AGING Searching for the Secrets Of the Super Old More and more people are living past 110. Can they show us all how to age gracefully? They were born when the years still started Perls of Boston University with “18.” They survived global traumas such School of Medicine, head as World War I, World War II, and the Great of the New England Cen- Depression. They didn’t succumb to pan- tenarian Study and its new demic flu, polio, AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, National Institutes of or clogged arteries. Supercentenarians, or Health–funded spinoff, the people who’ve survived to at least age 110, are New England Supercente- longevity champions. narian Study. Researchers suspect that some Living to 100 is unlikely enough. Accord- of the oldsters included in the tally had already he requires three types of verification: proof ing to one estimate, about seven in 1000 peo- died and that others—or their relatives—were of birth, preferably a birth certificate; proof ple reach the century milestone. And at that lying about their ages. Drawing on Medicare of death, if the person is no longer alive; and age, the odds of surviving even one more year enrollment figures, two U.S. government “continuity” documentation, such as a dri- are only 50–50, says James Vaupel, director of actuaries put the number of supercentenarians ver’s license or marriage certificate, that the Max Planck Institute for Demographic in the year 2000 at a mere 105. And in 2002, shows that the putative supercentenarian is Research in Rostock, Germany. Making it 139 people claiming to be at least 110 were the person listed in the birth record.