Rodman Guns Which Followed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm06220211.Pdf

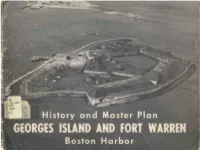

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Excavation of a Fort Fisher Bombproof

Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives & History Department of Cultural Resources Kure Beach, NC 1981 Excavation of a Fort Fisher Bombproof By Gordon P. Watts, Jr. Mark Wilde-Ramsing Richard W. Lawrence Dina B. Hill Underwater Archaeology Branch North Carolina Division of Archives and History 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF FIGURES___________________________________________________iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS _______________________________________________ iv INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________ 1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ___________________________________________ 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE WORK __________________________________________ 4 METHODS____________________________________________________________ 5 CONDITION OF STRUCTURAL REMAINS ________________________________ 9 ARCHITECTURAL AND CONSTRUCTION FEATURES ____________________ 21 ARTIFACTS__________________________________________________________ 26 CONCLUSIONS ______________________________________________________ 27 UAB 1981 Watts, Wilde-Ramsing, Lawrence, Hill ii TABLE OF FIGURES Figure 1: Location of excavation site______________________________________________________ 1 Figure 2: Excavation site in 1971 ________________________________________________________ 7 Figure 3: Cave-in at the excavation site____________________________________________________ 7 Figure 4: Overburden being removed by hand ______________________________________________ 8 Figure 5: Mobile crane utilized during excavation ___________________________________________ -

{PDF} the Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle Ebook, Epub

THE PATTERN 1853 ENFIELD RIFLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter G. Smithurst,Peter Dennis | 80 pages | 20 Jul 2011 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781849084857 | English | Oxford, England, United Kingdom The Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle PDF Book The Enfield , also known as Pattern Enfield, was a 15mm. The idea of having anything which might be tainted with pig or beef fat in their mouths was totally unacceptable to the sepoys, and when they objected it was suggested that they were more than welcome to make up their own batches of cartridges, using a religiously acceptable greasing agent such as ghee or vegetable oil. A further suggestion that the Sepoys tear the cartridges open with their hands instead of biting them open was rejected as impractical — many of the Sepoys had been undertaking musket drill daily for years, and the practice of biting the cartridge open was second nature to them. An engraving titled Sepoy Indian troops dividing the spoils after their mutiny against British rule , which include a number of muskets. Bomford Columbiad cannon Brooke rifled cannon Carronade cannon Dahlgren cannon Paixhans cannon Rodman Columbiad cannon Whitworth pounder rifled cannon. Numbers of Enfield muskets were also acquired by the Maori later on in the proceedings, either from the British themselves who traded them to friendly tribes or from European traders who were less discriminating about which customers they supplied with firearms, powder, and shot. For All the Tea in China. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Related Content. Coehorn mortar. It has been estimated that over , P53 Enfields were imported into America and saw service in every major engagement from the Battle of Shiloh April, and the Siege of Vicksburg May , to the final battles of With war breaking out between the Russians and the Turks, Britain realized that it was only a matter of time before they would be drawn into the conflict. -

No. 13: the CONFEDERATE UPPER BATTERY SITE, GRAND GULF

Archaeological Report No. 13 THE CONFEDERATE UPPER BATTERY SITE, GRAND GULF, MISSISSIPPI EXCAVATIONS, 1982 William C. Wright Mississippi Department of Archives and History and Grand Gulf Military Park Monu&ent 1984 MISSISSIPPI DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY Archaeological Report No. 13 Patricia Kay Galloway Series Editor Elbert R. Hilliard Director Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 84-62001 ISBN: 0-938896-38-5 Copyright 1984 Mississippi Department of Archives and History TABLE OF CONTENTS Personnel ii Acknowledgements iii Introduction iv Goals v The Military Struggle 1 Historical Background 1 Notes •.••..•••••...•• 33 The Upper Battery Site 41 Notes .••••••.••.•. 43 Procedures and Methods •••••. 45 Conclusion •.•••..•.••.• 49 Artifact Inventory 56 References 64 i DIRECTOR William C. Wright Historical Archaeologist Mississippi Department of Archives and History CREW Marc C. Hammack B.A. University of Mississippi Lee M. Hilliard Mississippi State University James C. Martin B.A. Mississippi College Baylor University School of Law James R. "Binky" Purvis M.S. Delta State University VOLUNTEERS Phillip Cox, Park Manager Grand Gulf State Military Monument Robert Keyes Tom Maute Tommy Presson Vicksburg Artifact Preservation Society ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS At the end of every excavation the archaeologist finds he or she is indebted to a multitude of people for their assistance. support. and labors. This archaeologist is no different. but it is nearly impossible to include everyone. and for this I apologize should I omit an individual who rightfully deserves recognition. However, I would certainly be remiss if I did not take this opportunity to thank my crew: Marc Hammack. Lee Hilliard. rim Martin. and Binky Purvis. whose dedication and labors are forever appreciated. -

SAN LUIS OBISPO Home

256 SUVCW Dept. of California & Pacific - Civil War & Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Memorials Project CA – SAN LUIS OBISPO Home: http://www.suvpac.org/memorials.html Case Name: CA-San Luis Obispo-San Luis Obispo-SanLuisCem-GAR Plot-Cannon State: California Type: County: San Luis Obispo Cannon, nicknamed "Big Bill." Bureau of Ordinance shell gun of 4500 pounds, 32-pdr, foundry Location: Builders Foundry [marked JFG], registry #333, foundry #62, inspector TAH on trunnion [Timothy San Luis Cemetery (Lady Family/Sutcliff Cemetery) - Atwater Hunt], cast 1866, weight 4530 pounds, preponderance 360 pounds. Served on the USS 2100 South Higuera and Elk Lane, San Luis Obispo, Kearsarge. Refurbished 1998. Note: The description on the accompanying plaque misidentifies this CA. gun as a Dahlgren. and the year and place of manufacture refer to the carriage, not the gun. Photos: Latitude: North 35.26230 (Google Earth) Right: Photo of cannon, Longitude: West 120.67007 by D. Enderlin March 2012 [additional photos Reported by: on file] Stark list, Armistead and Strobridge, 1998 Researched by: Edson T. Strobridge, Camp 21, 1998 Status: Under Assessment X Needs Further Investigation Completed X CWM-61 (assessment form) available Form CWM-62 (grant application) available Form 61 link: http://www.suvpac.org/memorials/forms/61CA-San%20Luis%20Obispo-San%20Luis%20Obispo-SanLuisCem-GAR%20Plot-Cannon.pdf Notes: Edson T. Strobridge relocated the gun, refurbished it, and returned the piece to its historical location. He then provided a plaque. Resubmission report with minor changes, 12 Apr 2002. Inscription: "BIG BILL" Model 1864 Dahlgren Smoothbore 32 Pounder U.S. Naval Cannon Manufactured by the Architectural Iron Works of New York in 1865, this gun, no. -

Download the Florida Civil War Heritage Trail

Florida -CjvjlV&r- Heritage Trail .•""•^ ** V fc till -/foMyfa^^Jtwr^— A Florida Heritage Publication Florida . r li //AA Heritage Trail Fought from 1861 to 1865, the American Civil War was the country's bloodiest conflict. Over 3 million Americans fought in it, and more than 600,000 men, 2 percent of the American population, died in it. The war resulted in the abolition of slavery, ended the concept of state secession, and forever changed the nation. One of the 1 1 states to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy, Florida's role in this momentous struggle is often overlooked. While located far from the major theaters of the war, the state experienced considerable military activity. At one Florida battle alone, over 2,800 Confederate and Union soldiers became casualties. The state supplied some 1 5,000 men to the Confederate armies who fought in nearly all of the major battles or the war. Florida became a significant source of supplies for the Confederacy, providing large amounts of beef, pork, fish, sugar, molasses, and salt. Reflecting the divisive nature of the conflict, several thousand white and black Floridians also served in the Union army and navy. The Civil War brought considerable deprivation and tragedy to Florida. Many of her soldiers fought in distant states, and an estimated 5,000 died with many thousands more maimed and wounded. At home, the Union blockade and runaway inflation meant crippling scarcities of common household goods, clothing, and medicine. Although Florida families carried on with determination, significant portions of the populated areas of the state lay in ruins by the end of the war. -

The Civil War Diary of Hoosier Samuel P

1 “LIKE CROSSING HELL ON A ROTTEN RAIL—DANGEROUS”: THE CIVIL WAR DIARY OF HOOSIER SAMUEL P. HERRINGTON Edited by Ralph D. Gray Bloomington 2014 2 Sergeant Samuel P. Herrington Indianapolis Star, April 7, 1912 3 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 5 CHAPTERS 1. Off to Missouri (August-December 1861) 17 "There was no one rejected." 2. The Pea Ridge Campaign (January-March 15, 1862) 61 "Lord but how we made things hum." 3. Missouri Interlude (March 16-June 1862) 87 "There is a great many sick [and] wounded." 4. Moving Along the Mississippi (July-December 1862) 111 "We will never have so much fun if we stay ten years in the service." 5. The Approach to Vicksburg (January-May 18, 1863) 149 "We have quite an army here." 6. Vicksburg and Jackson (May 19-July 26, 1863) 177 ". they are almost Starved and cant hold out much longer." 7. To Texas, via Indiana and Louisiana (July 27-December 1863) 201 "The sand blows very badly & everything we eat is full of sand." 8. Guard Duty along the Gulf (January-May 28, 1864 241 "A poor soldier obeys orders that is all." 9. To the Shenandoah and Home (May 29-September 1864) 277 "I was at the old John Brown Fortress where he made his stand for Liberty and Justice." 4 The picture can't be displayed. 5 INTRODUCTION Indiana played a significant role in the Civil War. Its contributions of men and material, surpassed by no other northern state on a percentage basis, were of enormous importance in the total war effort. -

D:\Wolfback1\Book Transcriptions\1880 Ordnance

ORDNANCE Related Articles from Appleton’s Cyclopedia of Applied Mechanics, 1880 Page 1 of 45 ORDNANCE, CONSTRUCTION OF. The term ordnance includes artillery of all kinds in its most comprehensive signification. Within the last twenty years the art of using a gun and developing its power has been virtually transformed by the aid of scientific research and mechanical skill. This process of evolution is in active progress. The production of a gun more powerful than any hitherto known serves but as a challenge to the manufacture of armor capable of resisting the shot from that weapon; and success in this last involves efforts toward the construction of cannon of still greater penetrating energy. With the enormously heavy guns of modern times, new discoveries in the strength of gun-metals, in the art of making projectiles, in the nature of explosives, and in the resistance of various forms of armor, are made. These in turn react upon principles of gun construction previously deemed settled, and produce modifications in them ; and thus advancement is accomplished by the light of experiment alone. THEORY OF CONSTRUCTION.--Constituent Parts.-Cannon are classified as guns, howitzers, and mortars, or as field, mountain, prairie, siege, and seacoast cannon. Fig. 3252 represents an old form of cannon, which exhibits clearly the five principal parts into which nearly all guns are regarded as divided. These are the breech, A ; the first reënforce, B; the second reënforce, C; the chase, D ; and the swell of the muzzle, E. The breech is the solid part of the piece in the prolongation of the axis; its length should be from one to one and a quarter time the diameter of the bore, H. -

Overview History of Artillery Ordnance at Sandy Hook Proving Ground

J r~ r, This report is not a detailed history of the ^andy Hook Proving Ground itself, but it is or. attempt to £ive an overview history of what, kind of artillery ordnance v:us beiri£ tested at Sandy Hook botwecn 1&7^ and 1919, and what types of ordnance have been found at the Hook cince it became a National Recreation Area. The report includes the following sections: Pages 1-2. .Introduction . ;-S;Vv * ' Pages 2-15........Small Arms Ammunition K^; ; .: Pages 16-19.......Sandy Hook Ordnance Proving Ground: An Overview; Pages 20-32. Weapons tested at the Proving Ground from "°nh " Information) - . ;;^V| is>s?. Pages 33-^3 Types of Artillery & Artillery Projectiles? fir<i^it^e Prbv Ground from 187U to 1919 (listing probable; areas on: Sandy Hook). ' ;•-....£ Pages M*-l<6 Artillery Projectiles & Fuses, a short historyj ! Pages ^7-50 Smoothbore Ammunition (cannonballs) ; - Pages 5O-6U Rifle Projectiles: Field and. Coast Artillery Pages 65-67.. Bursting Charges in Projectiles: 1900, 1907, Page 68. .....Types of Projectiles for U.S. Cannon;'(-191Q)» •: Pages 69-70.......Colors for Projectiles • - .' Pages 70-71 Interior coatings of projectiles, shell bases,; ' ' '-,. V • •• ' Rockets. • •,"'••'.•"• Y' ' •"^-•'-'"": •••;... • ," '•••w. • ." - • - Pa«eu72 Types of. Shells . ", Bages 73-81 Artillery shell's and other ordnance found'at 1 . of Gateway National Recreation Area (yith lofei Pages'£2-87.......Sa,fety j^roceduKes to follow \-/heri .dealing with oiSdnance ^ .Large .Map shpwing ordnance ir.pact and target areas at 'the Sanfiy _ •'"'Proving Ground. (pz>c> L '>.r>"-Ji J '' •• •." -\M 200.1f C02NJ000402_0l.05_0001 This report wan put together at the request of the Vinitor Protection* Resource Management Ranger Division of the Sandy Hook Unit of Gateway National Recreation Area. -

~~ ;;Ks Vfj /WI3- /'7 O3s(D-:J.-15 19 NOVEMBER 1993

I' ------------------------------------------- ~~ ;;ks VfJ /WI3- /'7 o3S(D-:J.-15 19 NOVEMBER 1993 TO: Regional Director, Southeast Region FROM: Superintendent, Gulf Islands National Seasho£e SUBJ. : Project Completion Report - Cultural Resources reference 106 project # GuIS-12.--11 Attached for the information and use of the Regional Office is a co;,rrpletion report on the mounting of ""'--------historic ordnance on reproduction aluminum carriages at Fort Pickens and Fort "...._;;:'-- - Ba~r~J~s, Gulf Islands National Seashore. --<: .....~.~~ Also included are photographs and drawings, and original and/or revised specifications and scopes of work related to the project. signed at'I.:,'lchments '.!'/ . ~ ft?35/J)- ;)15 I section 106 completion Report project Number: l\ GUIS-92-11 project Name: MOUNT ORDNANCE IN HISTORIC FORTS I Date of completion: 19 NOVEMBER 1993 Description of Work Done: Fabrication by contractor of aluminum barbette carriage and chassis for M1840 24-pounder seacoast cannon. Fabrication by contractor. of aluminum barbette carriage and chassis for M1861 10-inch Rodman gun (converted to 8-inch rifle). Preservation work on 24-pounder seacoast gun (cat.' GUIS-1157) and two 8-inch Rodman rifles (cat.# GUIS-1150-1151)~ Prese~vation work on iron of 2 gun emplacements at Ft. Pickens, and 1 gun emplacement at Ft. Barrancas. Installation of 24-pounder on new carriage at Ft. Barrancas. Installation of one 8-inch Rod:nan rifle on new ca!:"riage at Ft. Pickens. Installation ,of one B-inch Rodman rifle on new concrete pedestal on parade ground of Ft. Pickens. Were additional requirements (if any) fulfilled? If so, how? If . not, why? New aluminum carriage has not yet been fabricated for 32-pounder gun en casemate at Ft . -

Conserving and Remounting Fort Jefferson's Cannon

National Park Service Dry Tortugas U.S. Department of the Interior Dry Tortugas National Park Conserving and Remounting Fort Jefferson’s Cannon Fort Jefferson was armed with many different types of cannons throughout its history. Some of the largest were the Parrot and Rodman Cannons. Parrott rifled cannon weigh 26,780 lbs and were designed to fire 300 lb projectiles a range of over 5 miles. The 15-inch Rodman weighs over 50,000 lbs and could fire a 440-pound shell over 3 1/2 miles. Parrott History The term “Parrott gun” refers to a series applied to the gun red-hot and then the gun of American Civil War-era rifled cannon was turned while pouring water down the designed by Captain Robert P. Parrott (1804- muzzle, allowing the band to attach uniformly. 1877). Parrott resigned from the US Army in 1836, becoming superintendent of the West These rifled guns were designed to fire projec- Point Iron and Cannon Foundry in Cold tiles and were manufactured in a large range of Spring, New York. sizes, from smaller 10-pounder field artillery up to the rare 300-pounder guns. The larger, In 1860 he invented the Parrott rifled gun, heavier guns were intended to be mounted which was manufactured with a combination in seacoast fortifications and for use on naval of cast and wrought iron. The cast iron made ships. Although accurate, cheaper and easier for an accurate gun, but was brittle enough to to make, the Parrott guns had a poor reputa- suffer fractures. Hence, a large wrought iron tion for safety. -

American Civil War Flags: Documents, Controversy, and Challenges- Harold F

AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 48/Winter 2001 The Atnerican Civil War ,.~~-,~.,.... -~~'-'C__ iv_ i__ I _W:.........~r Scho!arship in t4e 21st Cent ea Confere . ISSN: 1433-5239 € 3,00 AMERICAN STUDIES jOURNAL Number 48 Winter 2001 The Atnerican Civil War "Civil War Scholarship in the 21st Century" Selected Conference Proceedings ISSN: 1433-5239 i I Editor's Note Lutherstadt Wittenberg States and the Environment." Since the year 2002 marks November 2001 the five hundredth anniversary of the founding of the University of Wittenberg, the Leucorea, where the Center Dear Readers, for U.S. Studies in based, issue #50 will be devoted to education at the university level in a broad sense. Articles It is with some regret that I must give notice that this on university history, articles on higher education and so present issue of the American Studies Journal is my forth are very welcome. For further information on last as editor. My contract at the Center for U.S. Studies submitting an article, please see the Journal's web site. expires at the end of 2001, so I am returning to the United States to pursue my academic career there. At AUF WIEDERSEHEN, present, no new editor has been found, but the American Embassy in Germany, the agency that finances the Dr. J. Kelly Robison printing costs and some of the transportation costs of Editor the Journal, are seeking a new editor and hope to have one in place shortly. As you are aware, the editing process has been carried out without the assistance of an editorial assistant since November of 2000.