The Civil War Diary of Hoosier Samuel P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sultana Disaster, 27 Apr 1865

U.S. Army Military History Institute POW-Civil War Collections Division 950 Soldiers Drive Carlisle Barracks, PA 17013-5021 7 Mar 08 SULTANA DISASTER, 27 APR 1865 A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources CONTENTS General Sources.....p.1 Personal Memoirs….p.2 GENERAL SOURCES Bryant, William O. Cahaba Prison and the Sultana Disaster. Tuscaloosa, AL: U AL, 1990. 180 p. E612C2B77. Cogley, Thomas S. History of the Seventh Indiana Cavalry Volunteers with an Account of the Burning of the Steamer Sultana on the Mississippi River... Laporte, IN: Herald, l876. 272 p. E506.6.7th.C64. See pp. l83-87 for a lithograph of the Sultana, a brief account of the explosion, and partial list of unit losses. Elliot, James W. Transport to Disaster. New York: Holt, Rinehart, Winston, l962. 247 p. E595S84E45. Funk, Arville. "Hoosiers at the Sultana Disaster." Indiana Journal of Military History (Oct 1985): pp. 20-23. Per. Foote, Shelby L. The Civil War, A Narrative. Vol. 3: Red River to Appomattox. NY: Random House, 1974. pp. 1026-27. E468F7v3. Hawes, Jesse. Cahaba: A Story of Captive Boys in Blue. NY: Burr, 1888. 480 p. E612C2H3. Pages 163-99 contain first-person account of the disaster, including conditions aboard the vessel and rescue efforts. Jackson, Rex T. The Sultana Saga: The Titanic of the Mississippi. Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 2003. 135 p. E595S84J33. Levstik, Frank R. "The Sultana Disaster." CW Times Illustrated (Jan 1974): 18-25. Per. Sultana Disaster p.2 Potter, Jerry. "The Sultana Disaster: Conspiracy of Greed." Blue & Gray (Aug 90): 8-24 & 54-59. Per. -

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

Ocm06220211.Pdf

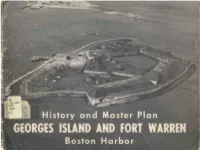

THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS--- : Foster F__urcO-lo, Governor METROP--�-��OLITAN DISTRICT COM MISSION; - PARKS DIVISION. HISTORY AND MASTER PLAN GEORGES ISLAND AND FORT WARREN 0 BOSTON HARBOR John E. Maloney, Commissioner Milton Cook Charles W. Greenough Associate Commissioners John Hill Charles J. McCarty Prepared By SHURCLIFF & MERRILL, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL CONSULTANT MINOR H. McLAIN . .. .' MAY 1960 , t :. � ,\ �:· !:'/,/ I , Lf; :: .. 1 1 " ' � : '• 600-3-60-927339 Publication of This Document Approved by Bernard Solomon. State Purchasing Agent Estimated cost per copy: $ 3.S2e « \ '< � <: .' '\' , � : 10 - r- /16/ /If( ��c..c��_c.� t � o� rJ 7;1,,,.._,03 � .i ?:,, r12··"- 4 ,-1. ' I" -po �� ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to acknowledge with thanks the assistance, information and interest extended by Region Five of the National Park Service; the Na tional Archives and Records Service; the Waterfront Committee of the Quincy-South Shore Chamber of Commerce; the Boston Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; Lieutenant Commander Preston Lincoln, USN, Curator of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion; Mr. Richard Parkhurst, former Chairman of Boston Port Authority; Brigardier General E. F. Periera, World War 11 Battery Commander at Fort Warren; Mr. Edward Rowe Snow, the noted historian; Mr. Hector Campbel I; the ABC Vending Company and the Wilson Line of Massachusetts. We also wish to thank Metropolitan District Commission Police Captain Daniel Connor and Capt. Andrew Sweeney for their assistance in providing transport to and from the Island. Reproductions of photographic materials are by George M. Cushing. COVER The cover shows Fort Warren and George's Island on January 2, 1958. -

Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2017 Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign George David Schieffler University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Schieffler, George David, "Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 2426. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2426 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by George David Schieffler The University of the South Bachelor of Arts in History, 2003 University of Arkansas Master of Arts in History, 2005 August 2017 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________ Dr. Daniel E. Sutherland Dissertation Director ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dr. Patrick G. Williams Committee Member Committee Member Abstract “Civil War in the Delta” describes how the American Civil War came to Helena, Arkansas, and its Phillips County environs, and how its people—black and white, male and female, rich and poor, free and enslaved, soldier and civilian—lived that conflict from the spring of 1861 to the summer of 1863, when Union soldiers repelled a Confederate assault on the town. -

From Hälsingland to Bloody Shiloh and Beyond

From Hälsingland to Bloody Shiloh and beyond A Swedish-American farm boy in the American Civil War. Part 2 BY PAUL SWARD The Disastrous Red The 43rd Illinois departed Little wagon train was also attacked by the Rock on March 23rd as part of Gene- Confederates who defeated and cap- River Campaign ral Steele’s forces. From the very tured the three regiments of Union The Red River Campaign is a little beginning things did not portend troops guarding the wagon train. known Union defeat that is best well. The Arkansas countryside that Over 1,300 men were lost.3 described as a fiasco. The object of the they marched through was sparsely campaign was to capture Shreveport, populated with rugged hills alter- Retreat Louisiana, and gain control of the nating with pine barrens and Red River which would lead to the General Steele was now in an un- swamps. It was described as a how- tenable position. He still had inade- capture of east Texas. The plan called ling wilderness.2 What few roads for Union General Banks to lead an quate supplies and no way of ob- there were became quagmires with th army up the Red River, accompanied taining any. After dark on April 26 a small amount of rain. Because of rd by the Union Navy. General Steele the 43 Illinois, along with all Steele’s his concern about supplying his troops, quietly abandoned Camden would march south from Little Rock troops, Steele immediately put his and both forces would converge on and began the long retreat back to men on half rations. -

Rules and Options

Rules and Options The author has attempted to draw as much as possible from the guidelines provided in the 5th edition Players Handbooks and Dungeon Master's Guide. Statistics for weapons listed in the Dungeon Master's Guide were used to develop the damage scales used in this book. Interestingly, these scales correspond fairly well with the values listed in the d20 Modern books. Game masters should feel free to modify any of the statistics or optional rules in this book as necessary. It is important to remember that Dungeons and Dragons abstracts combat to a degree, and does so more than many other game systems, in the name of playability. For this reason, the subtle differences that exist between many firearms will often drop below what might be called a "horizon of granularity." In D&D, for example, two pistols that real world shooters could spend hours discussing, debating how a few extra ounces of weight or different barrel lengths might affect accuracy, or how different kinds of ammunition (soft-nosed, armor-piercing, etc.) might affect damage, may be, in game terms, almost identical. This is neither good nor bad; it is just the way Dungeons and Dragons handles such things. Who can use firearms? Firearms are assumed to be martial ranged weapons. Characters from worlds where firearms are common and who can use martial ranged weapons will be proficient in them. Anyone else will have to train to gain proficiency— the specifics are left to individual game masters. Optionally, the game master may also allow characters with individual weapon proficiencies to trade one proficiency for an equivalent one at the time of character creation (e.g., monks can trade shortswords for one specific martial melee weapon like a war scythe, rogues can trade hand crossbows for one kind of firearm like a Glock 17 pistol, etc.). -

The Doolittle Family in America, 1856

TheDoolittlefamilyinAmerica WilliamFrederickDoolittle,LouiseS.Brown,MalissaR.Doolittle THE DOOLITTLE F AMILY IN A MERICA (PART I V.) YCOMPILED B WILLIAM F REDERICK DOOLITTLE, M. D. Sacred d ust of our forefathers, slumber in peace! Your g raves be the shrine to which patriots wend, And swear tireless vigilance never to cease Till f reedom's long struggle with tyranny end. :" ' :,. - -' ; ., :; .—Anon. 1804 Thb S avebs ft Wa1ts Pr1nt1ng Co., Cleveland Look w here we may, the wide earth o'er, Those l ighted faces smile no more. We t read the paths their feet have worn, We s it beneath their orchard trees, We h ear, like them, the hum of bees And rustle of the bladed corn ; We turn the pages that they read, Their w ritten words we linger o'er, But in the sun they cast no shade, No voice is heard, no sign is made, No s tep is on the conscious floor! Yet Love will dream and Faith will trust (Since He who knows our need is just,) That somehow, somewhere, meet we must. Alas for him who never sees The stars shine through his cypress-trees ! Who, hopeless, lays his dead away, \Tor looks to see the breaking day \cross the mournful marbles play ! >Vho hath not learned in hours of faith, The t ruth to flesh and sense unknown, That Life is ever lord of Death, ; #..;£jtfl Love" ca:1 -nt ver lose its own! V°vOl' THE D OOLITTLE FAMILY V.PART I SIXTH G ENERATION. The l ife given us by Nature is short, but the memory of a well-spent life is eternal. -

Mise En Page 1

10 DÉCEMBRE 2010 VENTE A PARIS DROUOT RICHELIEU - SALLE 10 Le vendredi 10 décembre 2010 A 14 heures ART DE L’ISLAM, ARCHÉOLOGIE, HAUTE ÉPOQUE ET EXTRÊME-ORIENT CÉRAMIQUES EUROPÉENNES DECORATIONS ET ARMES ESTAMPES ET PLANCHES ORIGINALES DE BANDE DESSINÉE DESSINS, TABLEAUX ET SCULPTURES DES XVIème au XXème SIÈCLES OBJETS D’ART ET MOBILIER DU XXème SIÈCLE OBJETS D’ART ET MOBILIER ANCIENS EXPERTS ART ISLAMIQUE ET ORIENTAL DESSINS, TABLEAUX ET SCULPTURES Mme Marie-Christine DAVID ème ème 21 rue du Faubourg Montmartre, 75009 Paris DES XIX ET XX SIÈCLES Tél. : 01 45 62 27 76 - Fax : 01 48 24 30 95 M. Frederick CHANOIT [email protected] 12, rue Drouot, 75009 Paris Tél. / Fax : 01 47 70 22 33 ARCHÉOLOGIE ARMES [email protected] M. Jean-Claude DEY M. Daniel LEBEURRIER Cabinet PERAZZONE-BRUN 8 bis Rue Schlumberger, 92430 Marnes La Coquette 9, rue de Verneuil, 75007 Paris M. Roberto PERAZZONE et M. Irénée BRUN Tél: 01.47.41.65.31. - Fax: 01.47.41.17.67. Tél./ Fax : 01 42 61 37 66 14, rue Favart, 75002 [email protected] [email protected] Tél. / Fax : 01 42 60 45 45 ARCHÉOLOGIE ET HAUTE ÉPOQUE ESTAMPES [email protected] M. Jean ROUDILLON Mme Sylvie COLLIGNON M. Eric SCHOELLER 206, boulevard Saint Germain, 75007 Paris 45, rue Sainte Anne, 75001 Paris 15, rue Drouot 75009 Paris Tél. : 01 42 22 85 97 - Fax : 01 45 48 55 54 Tél. : 01 42 96 12 17 - Fax : 01 42 96 12 36 Tél. : 01 47 70 15 22 - Fax : 01 42 46 44 91 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] M. -

EMORIES of Rour I EARS SERVICE

Under the Stars '"'^•Slfc- and Bars ,...o».... MEMORIEEMORIES OF FOUrOUR YI :EAR S SERVICE WITH TiaOR OGLETHORPES OF Jy WAWER A. CI^ARK, •,-'j-^j-rj,--:. j^rtrr.:f-'- H <^1 OR, MEMORIES OF FOUR YEARS SERVICE AVITH THE OGLETHORPES, OF AUGUSTA, GEORGIA BY WALTER A. CLARK, ORDERLY SERGEANT. AUGUSTA, GA Chronicle Printing Company. DEDICATION To the surviving members of the Oglethorpes, with whom I shared the dangers and hardships of soldier life and to the memory of those who fell on the firing line, or from ghostly cots in hospital Avards, with fevered lip and wasted forms, "drifted out on the unknown sea that rolls round all the Avorld," these memories are tenderly and afifectionatelv inscribed bv their old friend and comrade. PREFACE. For the gratification of my old comrades and in grate- hil memory of their constant kindness during all our years of comradeship these records have been written. The Avriter claims no special qualification for the task save as it may lie in the fact that no other survivor of the Company has so large a fund of material from which to draw for such a purpose. In addition to a war journal, whose entries cover all my four years service, nearly every letter Avritten by me from camp in those eventful years has been preserved. WHiatever lack, therefore, these pages may possess on other lines, they furnish at least a truth ful portrait of what I saw and felt as a soldier. It has beeen my purpose to picture the lights rather than the shadoAvs of our soldier life. -

Camp Communicator April 2021

x Frederick H. Hackeman CAMP 85 April 2021 Commander’s Ramblings Brothers, Well, as you can see this is LATE in getting out. I can only say that events conspired against me in keeping on schedule. I can only hope that everyone is keeping safe and that we’ve all been able to get vaccinated. If we have then that makes it somewhat easier for us to have an in-person meeting in May. Chuck called and said that he would be checking on a venue to see if we might be able to meet. War So, let’s get down to it. June has the Flag Day parade and I’ll be registering us for that event. So, we need to check on our members to see if we can all participate. Ray should be able to have the trailer for some of us to ride on and do the waving to whatever crowd is on hand. Accordingly, some of our members could once again walk in front and fire their muskets to thrill the crowds and perhaps have one carry our camp flag. As I’ve said previously, those riding on the trailer would be sitting and waving and they don’t need to be dressed in CW garb. Those of us with the outfits should consider wearing them to help the group look spiffy and attract attention. The Department Encampment is scheduled for May1st and Commander to Page 2 I’ll be attending. Mainly because I have to be there as I’m In this Issue Veterans of the Civil Page 1 - Commander’s Ramblings Page 3 - The Sultana Page 4 - National & Department Events Page 5 - Civil War Time Line - April Page 11 - Member Ancestors List Sons of the Union Camp Communicator Next Camp Meeting **May 13**, 2021 -6:30 p.m. -

August 24,1888

i _ PRESS. ESTABLISHED JUNE 23, 1862-VOL. FRIDAY AUGUST 1888. 27._*_PORTLAND, MAINE, MORNING, 24, [LWaM PRICE THREE CENTS SPKMAL AOTHKK. niWRLLANEUl’R. him After the trunks tions. land had three times the PRESIDENT CLEVELAND TO BE THERE. pushed away. rilling So also may “policemen, letter car- population of these can tariff than lt was under all ran for the railroad Foster revenue Western States in with an A MESSAGE FROM they track, BANGOR’S GREAT DAY. riers, officers, pensioners and their 1800, aggregate the free trade tariff in 185D. | THE PRESIDENT ahead and Weed behind. When wives.” ac- wealth hundred [Applause. way they So also may, “minors, having of|thirty-seven million ($3,- The Democracy under the control of the reaehed the track Weed said, “I don’t think counts in their own names.” So also may 700,000,000.) To-day the population of these South could • The Croat and Attraction at not and would not protect the Leading 1 got my share of that.” Witness said, “You “females, described as married States is about the same as the only women, Western North, but they did take care of Southern Recommending thelCeaaation of the PARASOLS! the Eastern Fair. more than and widows or So also their in the got your share, spinsters.” may “trust States, while wealth, tweuty Industries as was shown In the Mills bill. at any rate we will fix it accounts” be all between 1800 and 1880, increased Bonding Privilege deposited, “including years only They made vegetables, lumber, salt and ever our clock of later,” bnt he Weed two more rolls of accounts for minors.” three in to eleven The balance of Fancy gave An Entlinsiaslie Multitude Give Mr. -

![Colt 1851 Navy Revolver Manual.PDF [Online Books] Colt 1851 Navy Revolver Manual](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7183/colt-1851-navy-revolver-manual-pdf-online-books-colt-1851-navy-revolver-manual-587183.webp)

Colt 1851 Navy Revolver Manual.PDF [Online Books] Colt 1851 Navy Revolver Manual

[Online Books] Free Download Colt 1851 navy revolver manual.PDF [Online Books] Colt 1851 Navy Revolver Manual If you are searched for a ebook Colt 1851 navy revolver manual in pdf format, then you have come on to the loyal site. We furnish the complete release of this ebook in txt, doc, ePub, DjVu, PDF formats. You can reading Colt 1851 navy revolver manual online or load. As well as, on our site you may read the manuals and diverse artistic books online, either download them as well. We want draw on your regard what our site not store the book itself, but we grant reference to website where you may downloading either read online. So that if need to load pdf Colt 1851 navy revolver manual , then you have come on to loyal website. We own Colt 1851 navy revolver manual doc, PDF, txt, DjVu, ePub forms. We will be happy if you go back more. We have made sure that you find the PDF Ebooks without unnecessary research. And, having access to our ebooks, you can read Colt 1851 navy revolver manual online or save it on your computer. To find a Colt 1851 navy revolver manual, you only need to visit our website, which hosts a complete collection of ebooks. Colt revolvers - navy for sale - guns U.S. Martial Colt 1851 Navy .36 caliber revolver. For sale is a cased Colt 1851 Navy with all the goodies.. Gun is still tight and functions properly. Colt 1851 navy for sale buy colt 1851 navy Find colt 1851 navy for sale at GunBroker.com, You can buy colt 1851 navy with confidence from thousands of sellers who Colt 1851 Navy Revolver, Mfg'd 1863 Colt m1851 and m1861 navy revolvers - authentic Hallo! The most accurate and "authentic" reproduction M1851 Colt Navy WAS, is, the round brass one made by "Colt" as their line of Second Generation circa 1971 Colt 1851 navy revolver, mfg'd 1863 ( original ) Colt 1851 Navy Revolver, Mfg'd 1863 ( Original ) Auction # 498076010 Please if you are the buyer or seller to see more Shooting 44 caliber 1851 navy revolvers.mov - Feb 01, 2012 Shooting replica.44 caliber Colt 1851 Navy revolvers from Pietta and Armi San Marcos.