Latino Identity in Allende's Historical Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read 2020 Book Lists

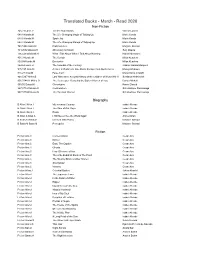

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

8 Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero

Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero Victoria Kearley Introduction Such did the theatrical trailer for The Mask of Zorro (Campbell, 1998) proclaim of Antonio Banderas’s performance as the masked adventurer, promising the viewer a sexier and more daring vision of Zorro than they had ever seen before. This paper considers this new image of Zorro and the way in which an iconic figure of modern popular culture was redefined through the performance of Banderas, and the influence of his contemporary star persona, as he became the first Hispanic actor ever to play Zorro in a major Hollywood production. It is my argument that Banderas’s Zorro, transformed from bandit Alejandro Murrieta into the masked hero over the course of the film’s narrative, is necessarily altered from previous incarnations in line with existing Hollywood images of Hispanic masculinity when he is played by a Hispanic actor. I will begin with a short introduction to the screen history of Zorro as a character and outline the action- adventure hero archetype of which he is a prime example. The main body of my argument is organised around a discussion of the employment of three of Hollywood’s most prevalent and enduring Hispanic male types, as defined by Latino film scholar, Charles Ramirez Berg, before concluding with a consideration of how these ultimately serve to redefine the character. Who is Zorro? Zorro was originally created by pulp fiction writer, Johnston McCulley, in 1919 and first immortalised on screen by Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (Niblo, 1920) just a year later. -

John P. Harrington Papers 1907-1959

THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME SEVEN A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: NATIVE AMERICAN HISTORY, LANGUAGE, AND CULTURE OF MEXICO/CENTRAL AMERICA/ SOUTH AMERICA I:DITRD Br Elaine L. Mills KRAUS INTER AJ 10 L Pl BLIC 110 Di ision of Kraus-Thom Jl )r 1lI1.allon LUl11tcd THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME SEVEN A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: Native American History, Language, and Culture of Mexico/Central America/South America Prepared in the National Anthropological Archives Department ofAnthropology National Museum ofNatural History Washington, D.C. THE PAPERS OF John Peabody Harringtan IN THE Smithsonian Institution 1907-1957 VOLUME SEVEN A GUIDE TO THE FIELD NOTES: Native American History, Language, and Culture of Mexico/Central America/South America EDITED BY Elaine L. Mills KRAUS INTERNATIONAL PUBLICATIONS A Division of Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited White Plains, N.Y. © Copyright The Smithsonian Institution 1988 All rights reserved. No part ofthis work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means-graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or taping, information storage and retrieval systems-without written permission ofthe publisher. First Printing Printed in the United States of America §TM The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science- Permanence of Papers for Contents Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data INTRODUCTION VII / V1/l Harrington, John Peabody. Scope and Content ofthis Publication VII / vu The papers ofJohn Peabody Harrington in the Smithsonian Institution, 1907 -1957. -

|||GET||| Portrait in Sepia 1St Edition

PORTRAIT IN SEPIA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Isabel Allende | 9780060898489 | | | | | Portrait in Sepia: A Novel Lists with This Book. I will start with what I didn't specifically enjoy. House of the Spirits is definitely the best of the trilogy, in fact I always recommend it for people just starting Allende and it can absolutely be read as standalone, however Daughter of Fortune and Portrait in Sepia should be read together to be greater appreciated. Her doting Chinese grandfather, Tao Chi'en, a physician, secretly rescues terrified children, transported in boat cages from China, to be sex-trafficked by exploiters in San Fran's China town. Others have mentioned Paulina del Valle as the main character, and I think there's some truth to that although I see her in more of a supporting role : she raises Aurora and is around for most of Portrait in Sepia 1st edition book, and certainly has the stronger personality of the two. Should I read the trilogy again, it will most definitely be in chronological order. The only nice thing I can say about it is that I learned something about Chilean history, I guess. There is a decidedly Latin beat to the flow of her sentences. When Alexander Cold's mother falls ill, the fifteen-year-old is sent to stay with his eccentric When she is forced to recognize her betrayal at the hands of the man she loves, and to cope with the resulting solitude, she decides to explore the mystery of her past. One other thing that I didn't like too much which I think is common in historical novel is how the main characters seems to bring C20th thinking an philosophy to a different time period. -

New Orleans Nostalgia "Zorro Rides Again" Ned Hémard Copyright 2007

N EW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Zorro Rides Again In 1937, New Orleans became the first city in the United States to be provided funding under the Wagner Act. Contracts for the St. Thomas and Magnolia housing projects were the first signed by FDR under Senator Robert Wagner’s legislation, and with it the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) was created. A young LBJ was one of the principal authors of the Housing Act of 1937, and he saw to it that the first three grants were announced in alphabetical order (with Austin being mentioned before New Orleans and New York). Also that year, New Orleans saw the founding of a new carnival organization, the Knights of Hermes (which continues to charm the city with its annual parade). Hermes, HANO and housing were the talk of the town, and Hitler was the talk of the nation. For those who wanted some form of escapism, there was always the local movie house. Among numerous neighborhood theatres, there was the Bell, the Cortez, the Casino and the Carrollton (which had been rebuilt the year before). Or perhaps one visited the Imperial on Hagan Avenue (Jefferson Davis Parkway today) followed by a stop at the Parkway Bakery (also on Hagan … then as today). 1937 produced great films like Frank Capra’s “Lost Horizon”, the Marx Brothers in “A Day at the Races”, “Stella Dallas”, “Topper” and “The Awful Truth”. In addition to these classics were the serial Westerns from Republic, and 1937’s “Zorro Rides Again” was one of these twelve-chapter runs. -

Teaching Spanish Through Hispanic Art by Maria Tucker Telelearning

IUPUI/IMA Community Project > Activities > Instructional Units > Teaching spanish through hi... Page 1 of 4 Teaching Spanish Through Hispanic Art By Maria Tucker Telelearning Louisiana School Natchitoches, Louisiana Instructional Plan Title: Teaching Spanish Through Hispanic Art Keywords: Maps. Art, music, language, food, and culture Curriculum Area: Spanish Grade Level: Nine to twelve Size group: Whole class (8 to 12 students) Time to Complete Instructional Plan: Four weeks culminating project over a thee-month period This plan will lead to these Instructional Objectives: 1. Students will learn about the importance of Spanish language in U.S.A. 2. Students will learn the geography of Hispanic world. 3. Students will create a picture of their favorite artist and write about him/her. 4. Students will be able to communicate in Spanish what they have learned. 5. Students will learn to recognize and respect cultural differences. 6. Students will learn to sing Spanish songs and able to translate them. 7. Students will learn about the differences of Hispanic art of Hispanic countries 8. Students will learn about the connection between art and language. Indiana State Proficiencies: 1.4.2 Students demonstrate an understanding of the concept of culture though comparisons of the culture's studies and their own. 2. Students will acquire information and recognize the different Hispanic countries of the world. Materials and resources Maps nationalgeographic.com Art calendar Smithsonian American Art Museum http://nrnaa-rvther.si.edu/1001/index.html Hoosier Artist http://www.ulib.iuyui.edu/imls/hoosierar.html Books file://C:\Documents%20and%20Settings\Administrator\My%20Documents\OliveTree\IMLS\site\ac.. -

Reading Guide Paula

Reading Guide Paula By Isabel Allende ISBN: 9780061564901 Introduction When Isabel Allende's daughter, Paula, became gravely ill and fell into a coma, the author began to write the story of her family for her unconscious child. Paula seizes the reader like a novel of suspense, capturing the lives of Isabel's outrageous ancestors, both living and spiritual, while unabashedly accepting the magical world as both vital and real. The author writes of love and hate, peace and war, weaving together delightful and bitter childhood memories that represent amazing anecdotes of her youthful years and the most intimate secrets passed along in whispers. Questions for Discussion 1. Isabel speaks lovingly about all of her eccentric relatives and has special relationships with each one. What influence did each relative have on the author? How did each help to shape the author's life: Tata? Memé? Tió Ramon? Tió Pablo? Her mother? Granny? Mama Hilda? Paula? 2. As a child, Isabel was molested by a fisherman near her beach house in Chile. The author says she was scarred by the experience but no longer feels repugnance to it (page 109). She feels something closer to tenderness for the fisherman for not raping her. Why is she so forgiving? 3. Do you feel Tata had a role in the fisherman's death, or was his murder a bizarre coincidence, as are most episodes in the author's life? 4. Tata asks Isabel to help him die with dignity, but she is unable to fulfill her grandfather's wishes. Years later, long after Paula slipped into the coma, Isabel also feels she should be able to help end her daughter's suffering, but cannot. -

California History Online | the Physical Setting

Chapter 1: The Physical Setting Regions and Landforms: Let's take a trip The land surface of California covers almost 100 million acres. It's the third largest of the states; only Alaska and Texas are larger. Within this vast area are a greater range of landforms, a greater variety of habitats, and more species of plants and animals than in any area of comparable size in all of North America. California Coast The coastline of California stretches for 1,264 miles from the Oregon border in the north to Mexico in the south. Some of the most breathtaking scenery in all of California lies along the Pacific coast. More than half of California's people reside in the coastal region. Most live in major cities that grew up around harbors at San Francisco Bay, San Diego Bay and the Los Angeles Basin. San Francisco Bay San Francisco Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in the world, covers some 450 square miles. It is two hundred feet deep at some points, but about two-thirds is less than twelve feet deep. The bay region, the only real break in the coastal mountains, is the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone and Coast Miwok Indians. It became the gateway for newcomers heading to the state's interior in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Tourism today is San Francisco's leading industry. San Diego Bay A variety of Yuman-speaking people have lived for thousands of years around the shores of San Diego Bay. European settlement began in 1769 with the arrival of the first Spanish missionaries. -

Lights! Camera! Gallop!

Lights! Camera! Gallop! The story of the horse in film By by Lesley Lodge Published by Cooper Johnson Limited Copyright Lesley Lodge © Lesley Lodge, 2012, all rights reserved Lesley Lodge has reserved her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. ISBN: 978-0-9573310-1-3 Cover photo: Running pairs Copyright Paul Homsy Photography Taken in Ruby Valley in northern Nevada, USA. Shadowfax – a horse ‘so clever and obedient he doesn’t have a bridle or a bit or reins or a saddle’ (Lord of the Rings trilogy) Ah, if only it was all that simple . Contents Chapter One: Introducing... horses in film Chapter Two: How the horse became a film star Chapter Three: The casting couch: which horse for which part? Chapter Four: The stars – and their glamour secrets Chapter Five: Born free: wild horses and the wild horse film Chapter Six: Living free: wild horse films around the world Chapter Seven: Comedy: horses that make you laugh Chapter Eight: Special effects: a little help for horses Chapter Nine: Tricks and stunts: how did he do that? Chapter Ten: When things go wrong: spotting fakes and mistakes Chapter Eleven: Not just a horse with no name: the Western Chapter Twelve: Test your knowledge now Quotes: From the sublime to the ridiculous Bibliography List of films mentioned in the book Useful websites: find film clips – and more – for free Acknowledgements Photo credits Glossary About the author Chapter One Introducing….horses in film The concept of a horse as a celebrity is easy enough to accept – because, after all, few celebrities become famous for actually doing much. -

Isabel Allende

>> For the past nine years, booklovers of all ages have gathered in Washington D.C. to celebrate reading at the Library of Congresses National Book Festival. This year, the library is proud to commemorate a decade of words and wonder at the 10th Annual National Book Festival on September 25, 2010. President and Mrs. Obama are honorary chairs of the event, which provides D.C. locals and visitors from across the country and around the world the opportunity to see and meet their favorite authors, illustrators and characters. The festival, which is free and open to the public as always, will be held on the National Mall from 10 to 5:30, rain or shine. And joining me today, I have the pleasure of speaking with novelist Isabel Allende. She's a Chilean-American, and her work has been translated into more than 30 languages and have been best sellers in Europe, Latin America and Australia, selling more than 56 million copies. At the National Book Festival, Allende will talk about her latest book, Island Beneath the Sea. The novel, which is her 18th, chronicles the journey of Zarite, I hope I pronounced that right, >> Mm-hmm. >> which begins when she is sold into slavery as a nine-year old girl in 18th century Santa Domingo. Miss Allende, thank you so much for talking with me today. >> It's my pleasure. >> Now, Island Beneath the Sea is full of intricate historical details, which isn't surprising given your prowess in the genre. What lead you -- why did you begin writing historical fiction? What drew you to that? >> I started writing historical fiction when I came to California many years ago because I realized that San Francisco was only 150 years old at the time, and before that, it was a fertile village called Yerba Buena. -

Book Guide.Xlsx

Quiz NumberLanguage Title Author 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 118288 EN 11-Sep-01 Schier, Helga 124054 EN 10 Greatest Threats to Earth, The Reaume, Christopher J. 134959 EN 10 Inventors Who Changed the World Gifford, Clive 133278 EN 10 Leaders Who Changed the World Gifford, Clive 104417 EN 101 Questions About Sex and Sexuality: With AnswersBrynie, for the Faith Curious, Hickman Cautious, and Confused 28974 EN 101 Questions Your Brain Has Asked... Brynie, Faith 105551 EN 13 1/2 Lives of Captain Bluebear, The Moers, Walter 26051 EN 14th Dalai Lama: Spiritual Leader of Tibet, The Stewart, Whitney 100663 EN 1900-1919 Tames, Richard 56505 EN 1900-20: New Horizons Hayes, Malcolm 40855 EN 1900-20: The Birth of Modernism Gaff, Jackie 109883 EN 1900s from Teddy Roosevelt to Flying Machines (RevisedFeinstein, Edition), Stephen The 109884 EN 1910s from World War I to Ragtime Music (Revised Edition),Feinstein, The Stephen 87106 EN 1918 Influenza Pandemic, The Peters, Stephanie True 44513 EN 1920-40: Realism and Surrealism Gaff, Jackie 107762 EN 1920s from Prohibition to Charles Lindbergh (RevisedFeinstein, Edition), StephenThe 121177 EN 1929 Stock Market Crash, The Gitlin, Martin 107763 EN 1930s from the Great Depression to the Wizard of OzFeinstein, (Revised StephenEd), The 100665 EN 1930s, The Tames, Richard 106752 EN 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson (RevisedFeinstein, Edition), TheStephen 36116 EN 1940s from World War II to Jackie Robinson, The Feinstein, Stephen 106753 EN 1950s from -

Racism Towards Japanese-American in Isabel Allende's The

RACISM TOWARDS JAPANESE-AMERICAN IN ISABEL ALLENDE'S THE JAPANESE LOVER A THESIS BY FATIMAH ZAHRA REG. NO 150721015 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA RACISM TOWARDS JAPANESE-AMERICAN IN ISABEL ALLENDE'S THE JAPANESE LOVER A THESIS BY FATIMAH ZAHRA REG. NO 150721015 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dr. Martha Pardede, M.S. Dr. Alemina Perangin-angin, M.HUM NIP. 195212291979032001 NIP. 198001312019022001 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra From Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof. T. SilvanaSinar, M.A., Ph.D. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. NIP. 195409161980032003 NIP. 197502092008121002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of SarjanaSastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on. Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Rahmadsyah Rangkuti,MA.,Ph.D. ____________________ Dr. Martha Pardede, M.S. ____________________ Drs. Parlindungan Purba, M.HUM. ____________________ UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, FATIMAH ZAHRA, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS.