Isabel Allende

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read 2020 Book Lists

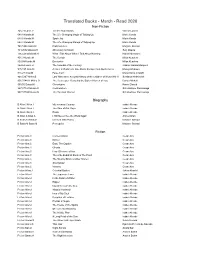

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

|||GET||| Portrait in Sepia 1St Edition

PORTRAIT IN SEPIA 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Isabel Allende | 9780060898489 | | | | | Portrait in Sepia: A Novel Lists with This Book. I will start with what I didn't specifically enjoy. House of the Spirits is definitely the best of the trilogy, in fact I always recommend it for people just starting Allende and it can absolutely be read as standalone, however Daughter of Fortune and Portrait in Sepia should be read together to be greater appreciated. Her doting Chinese grandfather, Tao Chi'en, a physician, secretly rescues terrified children, transported in boat cages from China, to be sex-trafficked by exploiters in San Fran's China town. Others have mentioned Paulina del Valle as the main character, and I think there's some truth to that although I see her in more of a supporting role : she raises Aurora and is around for most of Portrait in Sepia 1st edition book, and certainly has the stronger personality of the two. Should I read the trilogy again, it will most definitely be in chronological order. The only nice thing I can say about it is that I learned something about Chilean history, I guess. There is a decidedly Latin beat to the flow of her sentences. When Alexander Cold's mother falls ill, the fifteen-year-old is sent to stay with his eccentric When she is forced to recognize her betrayal at the hands of the man she loves, and to cope with the resulting solitude, she decides to explore the mystery of her past. One other thing that I didn't like too much which I think is common in historical novel is how the main characters seems to bring C20th thinking an philosophy to a different time period. -

Latino Identity in Allende's Historical Novels

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Purdue E-Pubs CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 13 (2011) Issue 4 Article 8 Latino Identity in Allende's Historical Novels Olga Ries University Diego Portales Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ries, Olga. "Latino Identity in Allende's Historical Novels." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 13.4 (2011): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1876> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Upcoming Fiction Highlights…

These books are coming soon! You can use this list to plan ahead and to search the library catalog. Visit our blog at www.thrall.org/BLB to explore even more books you might enjoy! Our librarians can help you find or reserve books! Upcoming Fiction Highlights… Tell Tale Rules of Magic Hiddensee by Jeffrey Archer by Alice Hoffman by Gregory Maguire “Archer returns with “Thrilling and exquisite, his eagerly-awaited, real and fantastical, The “Hiddensee recreates brand-new collection, Rules of Magic is a story the backstory of The a fascinating, exciting about the power of love Nutcracker, reimaging and sometimes reminding us that the how this entrancing poignant insight into only remedy for being creature came to be people he has met, human is to be true to carved and how it stories he has come yourself.” magically guided an ailing across, and countries little girl named Klara he has visited during (This novel is a prequel through a dreamy the past ten years.” to Practical Magic.) paradise on a snowy Christmas Eve.” More Forthcoming Fiction… Death In St. Petersburg - Tasha Alexander Cast Iron - Peter May Shattered Memories - V. C. Andrews The Mongrel Mage - L.E. Modesitt Parting Shot - Linwood Barclay The Devil You Know - Mary Monroe The Witches' Tree - M.C. Beaton Wyoming Winter - Diana Palmer The Relive Box and Other Stories - T.C. Boyle Deep Freeze - John Sandford Origin - Dan Brown The Tiger's Prey - Wilbur A. Smith Crazy Like a Fox - Rita Mae Brown Fairytale - Danielle Steel Children of the Fleet - Orson Scott Card An Irish Country Practice - Patrick Taylor The Stolen Marriage - Diane Chamberlain Even If It Kills Her - Kate White Two Kinds of Truth - Michael Connelly Lilac Lane - Sherryl Woods The Last Mrs. -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. -

Isabel Allende Biography

Isabel Allende Biography Isabel Allende—novelist, feminist, and philanthropist—is one of the most widely-read authors in the world, having sold more than 75 million books. Chilean born in Peru, Isabel won worldwide acclaim in 1982 with the publication of her first novel, The House of the Spirits, which began as a letter to her dying grandfather. Since then, she has authored more than twenty five bestselling and critically acclaimed books, including Daughter of Fortune, Island Beneath the Sea, Paula, The Japanese Lover, A Long Petal of the Sea and her most recent memoir, The Soul of a Woman. Translated into more than forty two languages, Allende’s works entertain and educate readers by interweaving imaginative stories with significant historical events. In addition to her work as a writer, Allende devotes much of her time to human rights causes. In 1996, following the death of her daughter Paula, she established a charitable foundation in her honor, which has awarded grants to more than 100 nonprofits worldwide, delivering life-changing care to hundreds of thousands of women and girls. More than 8 million have watched her TED Talks on leading a passionate life. She has received fifteen honorary doctorates, including one from Harvard University, was inducted into the California Hall of Fame, received the PEN Center Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2014, President Barack Obama awarded Allende the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, and in 2018 she received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation. -

Southfield Public Library

Southfield Public Library Japanese Lover by Isabel Allende Discussion questions used at SPL June 13 & 14, 2017 Discussion Questions issued by the publisher 1. As Alma Belasco reflects on her long life and the decisions she made to leave Ichimei and marry Nathaniel, do you think she would have done anything differently if she had had the chance? Why or why not? 2. At the beginning of her time at Lark House, Irina observes, “In itself age doesn’t make anyone better or wiser, but only accentuates what they have always been.” (p. 13) Do you think this is true of Alma Belasco? Why or why not? 3. Alma and Samuel Mendel are just two of many people who were forced to flee Europe during World War II—leaving their homes and loved ones behind. How does this affect the rest of their lives? How does it impact their view of family? 4. Consider this passage as the Fukudas and other Japanese and Japanese-American families board the buses to the internment camp at Topaz: “The families gave themselves up because there was no alternative and because by so doing they thought they were demonstrating their loyalty toward the United States and their repudiation of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. This was their contribution to the war effort.” (p. 88) How does the experience at Topaz affect each of the Fukudas’ sense of patriotism and their experiences as Americans? How does this change for each character over the course of internment? 5. Compare and contrast how the Belascos, a very formal family, uphold tradition, versus how the Fukudas, a family of recent immigrants and nisei, respect tradition while embracing their new Americanism. -

Isabel Allende Early Life She Was Born in 1942 in Lima, Peru, but Considers

Isabel Allende Early life She was born in 1942 in Lima, Peru, but considers herself Chilean since that is where her parents and all of her ancestors are from. They were living in Peru due to her father’s work. Father – Tomas Allende – Chilean diplomat Mother – Francisca Allende Isabel is the oldest child. She has two younger brothers, Pancho and Juan. All were born within the four years that her parents were together. Her father was not a good man. Her grandfather (Francisca’s parents - Tata/Meme) tried to convince Francisca not to marry him, but she was stubborn. From her book Paula: “The bride wore a sober satin gown and a defiant expression. I don’t know how the groom looked, because the photograph has been cropped; we can see nothing of him but one arm. As he led his daughter to the large room where an altar of cascading roses had been erected, Tata paused at the foot of the stairway. ‘There is still time to change your mind,’ he said. ‘Don’t marry him, Daughter, think better of it. Just give me a sign and I will run this mob out of here and send the banquet to the orphanage.’ My mother replied with an icy stare” (10-11). Francisca knew right away it was a mistake, even in the first days of the marriage as they sailed from Chile to Peru, where Tomas had been named secretary at the Chilean embassy “My mother spent the first two days of her honeymoon so nauseated by the tossing Pacific Ocean that she was unable to leave her stateroom; then, just as she felt a little better and could go outside to drink in the fresh air, her husband was felled by a toothache…. -

Slavery and African Oral Traditions in the Historical Novels of Manuel Zapata Olivella and Ana Maria Gonçalves by John Thomas Maddox IV

Dramas of Memory: Slavery and African Oral Traditions in the Historical Novels of Manuel Zapata Olivella and Ana Maria Gonçalves By John Thomas Maddox IV Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Spanish and Portuguese August, 2014 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Earl E. Fitz, Ph.D. Jane J. Landers, Ph.D. William Luis, Ph.D. Emanuelle K. Oliveira-Monte, Ph.D. Benigno Trigo, Ph.D. Copyright © by John Thomas Maddox IV All Rights Reserved ii To Luciana Silva, who made Brazil part of me and came with me in search of more, to Dad, who told me I would be the first Dr. Maddox, and to Mary Margaret, Joyce, and Regina Maddox, who cared for me in ways only they knew how. iii Acknowledgements The Department of Spanish and Portuguese is a team. My professors and colleagues have all contributed to my formation as a scholar, teacher, and professional, but I am especially grateful to Earl E. Fitz and William Luis. They have pushed me to be my best since my arrival at Vanderbilt, and their support and mentorship have led to many victories during my time here, including this dissertation. Emanuelle Oliveira-Monte, Benigno Trigo, and Cathy Jrade have devoted much time and effort to improving my scholarship. The Center for Latin American Studies, under Ted Fischer and Jane J. Landers, provided encouragement, camaraderie, and opportunities that shaped my research. Paula Covington and Kathy Smith supported my work with the Manuel Zapata Olivella Archives. -

Isabel Allende

Isabel Allende 24 books • translated into more than 42 languages • more than 75 million copies sold • 15 international honorary doctorates • more than 60 awards in over 15 countries • 2 feature-length movies • literary works adapted for movies, plays, musicals, operas, ballets and radio programs • Founder of The Isabel Allende Foundation to empower women and girls worldwide Biography ABOUT ISABEL It is very strange to write one’s biography because it is just a list of dates, events and achievements. In reality, the most important things about my life happened in the secret chambers of my heart and have no place in a biography. My most significant achievements are not my books, but the love I share with a few people, especially my family, and the ways in which I have tried to help others. When I was young, I often felt desperate: so much pain in the world and so little I could do to alleviate it. But now I look back at my life and feel satisfied because few days went by without me at least trying to make a difference. In any case, here is my biography. NAME Isabel Allende Llona NATIONALITY Chilean/American. Born in Perú to Chilean parents; became an American citizen in 1993. DATE OF BIRTH August 2, 1942 PROFESSION Writer Journalist Teacher—Creative Writing and Latin American Literature. WEBSITE / SOCIAL MEDIA isabelallende.com isabelallende.org facebook.com/isabelallende/ instagram.com/allendeisabel twitter.com/isabelallende ADVOCACY AND ACTIVISM In 1995 Isabel created the Isabel Allende Foundation to support the empowerment of women and girls worldwide (isabelallende.org). -

In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende

In the Midst of Winter Discussion Questions 1. Each of the three main characters—Lucia, Evelyn, and Richard—experiences some kind of isolation in their life. The book begins with Lucia physically isolated in her apartment during a snowstorm. In what other ways is she isolated? How is her isolation different from Evelyn’s? And from Richard’s? 2. Evelyn comes to the United States as a refugee fleeing violence. Compare her experience entering the country with that of other immigrants you know of or have read about. Why did they leave their native countries, and what were their first experiences as immigrants? Did you find any aspects of Evelyn’s journey surprising? It is said that the United States is a country of immigrants, and that immigrants made this country great. Do you agree? Why or why not? Did this book change the way you think about immigrants? If so, how? 3. Many immigrants in the United States currently work in caretaker jobs: as nannies Author: Isabel Allende taking care of small children, or as home health aides caring for the sick, elderly, or Originally published: dying. Do you know of any immigrants in these kinds of jobs? Do they encounter any June 1, 2017 difficulties similar to Evelyn’s? How do Frankie’s parents treat Evelyn? Why does she Original language: Spanish seem "invisible" to Frankie’s father? Genre: Romance novel, Historical fiction 4. Evelyn‘s relationship with Frankie is very special, and reveals a lot about her character. Why is she so successful at caring for him? In what ways does she expand his horizons? Do you know of someone who works with people who are physically, mentally, or emotionally challenged? Do they share any of Evelyn‘s character traits? 5.