Molecular Mechanisms of Programmed Necrotic Death Initiated by Intrinsic Death Signals Gary Xiaoshi Wang Washington University in St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DEDD (NM 001039712) Human Untagged Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for SC310813 DEDD (NM_001039712) Human Untagged Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: DEDD (NM_001039712) Human Untagged Clone Tag: Tag Free Symbol: DEDD Synonyms: CASP8IP1; DEDD1; DEFT; FLDED1; KE05 Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin Fully Sequenced ORF: >NCBI ORF sequence for NM_001039712, the custom clone sequence may differ by one or more nucleotides ATGGCGGGCCTAAAGCGGCGGGCAAGCCAGGTGTGGCCAGAAGAGCATGGTGAGCAGGAACATGGGCTGT ACAGCCTGCACCGCATGTTTGACATCGTGGGCACTCATCTGACACACAGAGATGTGCGCGTGCTTTCTTT CCTCTTTGTTGATGTCATTGATGACCACGAGCGTGGACTCATCCGAAATGGACGTGACTTCTTATTGGCA CTGGAGCGCCAGGGCCGCTGTGATGAAAGTAACTTTCGCCAGGTGCTGCAGCTGCTGCGCATCATCACTC GCCACGACCTGCTGCCCTACGTCACCCTCAAGAGGAGACGGGCTGTGTGCCCTGATCTTGTAGACAAGTA TCTGGAGGAGACATCAATTCGCTATGTGACCCCCAGAGCCCTCAGTGATCCAGAACCAAGGCCTCCCCAG CCCTCTAAAACAGTGCCTCCCCACTATCCTGTGGTGTGTTGCCCCACTTCGGGTCCTCAGATGTGTAGCA AGCGGCCAGCCCGAGGGAGAGCCACACTTGGGAGCCAGCGAAAACGCCGGAAGTCAGTGACACCAGATCC CAAGGAGAAGCAGACATGTGACATCAGACTGCGGGTTCGGGCTGAATACTGCCAGCATGAGACTGCTCTG CAGGGCAATGTCTTCTCTAACAAGCAGGACCCACTTGAGCGCCAGTTTGAGCGCTTTAACCAGGCCAACA CCATCCTCAAGTCCCGGGACCTGGGCTCCATCATCTGTGACATCAAGTTCTCTGAGCTCACCTACCTCGA TGCATTCTGGCGTGACTACATCAATGGCTCTTTATTAGAGGCACTTAAAGGTGTCTTCATCACAGACTCC CTCAAGCAAGCTGTGGGCCATGAAGCCATCAAGCTGCTGGTAAATGTAGACGAGGAGGACTATGAGCTGG -

Genetic and Genomic Analysis of Hyperlipidemia, Obesity and Diabetes Using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/Jngj) F2 Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Nutrition Publications and Other Works Nutrition 12-19-2010 Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P. Stewart Marshall University Hyoung Y. Kim University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Arnold M. Saxton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Jung H. Kim Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nutrpubs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stewart et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/713 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P Stewart1, Hyoung Yon Kim2, Arnold M Saxton3, Jung Han Kim1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes in humans and is closely associated with dyslipidemia and obesity that magnifies the mortality and morbidity related to T2D. The genetic contribution to human T2D and related metabolic disorders is evident, and mostly follows polygenic inheritance. The TALLYHO/ JngJ (TH) mice are a polygenic model for T2D characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose uptake and tolerance, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. -

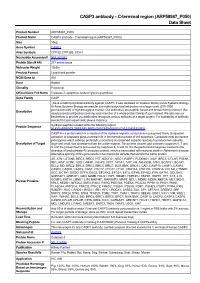

C-Terminal Region (ARP58987 P050) Data Sheet

CASP3 antibody - C-terminal region (ARP58987_P050) Data Sheet Product Number ARP58987_P050 Product Name CASP3 antibody - C-terminal region (ARP58987_P050) Size 50ug Gene Symbol CASP3 Alias Symbols CPP32; CPP32B; SCA-1 Nucleotide Accession# NM_032991 Protein Size (# AA) 277 amino acids Molecular Weight 12kDa Product Format Lyophilized powder NCBI Gene Id 836 Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Official Gene Full Name Caspase 3, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase Gene Family CASP This is a rabbit polyclonal antibody against CASP3. It was validated on Western Blot by Aviva Systems Biology. At Aviva Systems Biology we manufacture rabbit polyclonal antibodies on a large scale (200-1000 Description products/month) of high throughput manner. Our antibodies are peptide based and protein family oriented. We usually provide antibodies covering each member of a whole protein family of your interest. We also use our best efforts to provide you antibodies recognize various epitopes of a target protein. For availability of antibody needed for your experiment, please inquire (). Peptide Sequence Synthetic peptide located within the following region: NLKYEVRNKNDLTREEIVELMRDVSKEDHSKRSSFVCVLLSHGEEGIIFG CASP3 is a protein which is a member of the cysteine-aspartic acid protease (caspase) family. Sequential activation of caspases plays a central role in the execution-phase of cell apoptosis. Caspases exist as inactive proenzymes which undergo proteolytic processing at conserved aspartic residues to produce two subunits, Description of Target large and small, that dimerize to form the active enzyme. This protein cleaves and activates caspases 6, 7 and 9, and the protein itself is processed by caspases 8, 9 and 10. It is the predominant caspase involved in the cleavage of amyloid-beta 4A precursor protein, which is associated with neuronal death in Alzheimer's disease. -

Elabscience®

Tel:240-252-7368(USA) Fax:240-252-7376(USA) www.elabscience.com ® E-mail:[email protected] Elabscience Elabscience Biotechnology Inc. DEDD Polyclonal Antibody Catalog No. E-AB-67706 Reactivity H,M,R Storage Store at -20°C. Avoid freeze / thaw cycles. Host Rabbit Applications IHC Isotype IgG Note: Centrifuge before opening to ensure complete recovery of vial contents. Images Immunogen Information Immunogen Recombinant fusion protein of human DEDD (NP_001034801.1). GeneID 9191 Swissprot O75618 Synonyms DEDD,CASP8IP1,DEDD1,DEFT,FLDED1,KE05 Immunohistochemistry of paraffin- Product Information embedded Rat lung using DEDD Buffer PBS with 0.02% sodium azide, 50% glycerol, pH7.3. Polyclonal Antibody at dilution of Purify Affinity purification 1:100 (40x lens). Dilution IHC 1:50-1:100 Background This gene encodes a protein that contains a death effector domain (DED). DED is a protein-protein interaction domain shared by adaptors, Immunohistochemistry of paraffin- regulators and executors of the programmed cell death pathway. embedded Human esophagus using Overexpression of this gene was shown to induce weak apoptosis. Upon DEDD Polyclonal Antibody at dilution stimulation, this protein was found to translocate from cytoplasm to of 1:100 (40x lens). nucleus and colocalize with UBTF, a basal factor required for RNA polymerase I transcription, in the nucleolus. At least three transcript variants encoding the same protein have been found for this gene. Immunohistochemistry of paraffin- embedded Mouse kidney using DEDD Polyclonal Antibody at dilution of 1:100 (40x lens). For Research Use Only Focus on your research Thank you for your recent purchase. If you would like to learn more about antibodies,please visit www.elabscience.com. -

The Human Gene Connectome As a Map of Short Cuts for Morbid Allele Discovery

The human gene connectome as a map of short cuts for morbid allele discovery Yuval Itana,1, Shen-Ying Zhanga,b, Guillaume Vogta,b, Avinash Abhyankara, Melina Hermana, Patrick Nitschkec, Dror Friedd, Lluis Quintana-Murcie, Laurent Abela,b, and Jean-Laurent Casanovaa,b,f aSt. Giles Laboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Rockefeller Branch, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; bLaboratory of Human Genetics of Infectious Diseases, Necker Branch, Paris Descartes University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U980, Necker Medical School, 75015 Paris, France; cPlateforme Bioinformatique, Université Paris Descartes, 75116 Paris, France; dDepartment of Computer Science, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel; eUnit of Human Evolutionary Genetics, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité de Recherche Associée 3012, Institut Pasteur, F-75015 Paris, France; and fPediatric Immunology-Hematology Unit, Necker Hospital for Sick Children, 75015 Paris, France Edited* by Bruce Beutler, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, and approved February 15, 2013 (received for review October 19, 2012) High-throughput genomic data reveal thousands of gene variants to detect a single mutated gene, with the other polymorphic genes per patient, and it is often difficult to determine which of these being of less interest. This goes some way to explaining why, variants underlies disease in a given individual. However, at the despite the abundance of NGS data, the discovery of disease- population level, there may be some degree of phenotypic homo- causing alleles from such data remains somewhat limited. geneity, with alterations of specific physiological pathways under- We developed the human gene connectome (HGC) to over- come this problem. -

MCL1 and DEDD Promote Urothelial Carcinoma Progression

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on February 18, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0963 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. MCL1 and DEDD promote urothelial carcinoma progression Andrew L. Hong1,2,3, Jennifer L. Guerriero2, Mihir B. Doshi3, Bryan D. Kynnap2, Won Jun Kim2, Anna C. Schinzel2, Rebecca Modiste2, Amy J. Schlauch2, Rosalyn M. Adam1, David J. Kwiatkowski2,4, Rameen Beroukhim2,3, Anthony Letai2, Jonathan E. Rosenberg5,6,7, William C. Hahn2,3,4,7 1Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, 02115, USA 2Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts, 02215 USA 3Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, 415 Main Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02142 USA 4Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, Massachusetts, 02115 USA 5Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, New York 10065, USA. 6Weill Cornell Medical College, 1300 York Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA. 7These authors jointly directed this work. Running title: MCL1 and DEDD promote urothelial carcinoma progression The authors declare the following competing financial interests: J.L.G. receives sponsored research support from Eli Lilly and GlaxoSmithKline and is a paid consultant for GlaxoSmithKline. D.J.K. is a consultant for Genentech, AADi, and Novartis. R.B. receives 1 Downloaded from mcr.aacrjournals.org on September 24, 2021. © 2019 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on February 18, 2019; DOI: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0963 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. -

Death Effector Domain–Containing Protein (DEDD) Is Required for Uterine Decidualization During Early Pregnancy in Mice

Death effector domain–containing protein (DEDD) is required for uterine decidualization during early pregnancy in mice Mayumi Mori, … , Satoko Arai, Toru Miyazaki J Clin Invest. 2011;121(1):318-327. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI44723. Research Article Reproductive biology During intrauterine life, the mammalian embryo survives via its physical connection to the mother. The uterine decidua, which differentiates from stromal cells after implantation in a process known as decidualization, plays essential roles in supporting embryonic growth before establishment of the placenta. Here we show that female mice lacking death effector domain–containing protein (DEDD) are infertile owing to unsuccessful decidualization. In uteri of Dedd–/– mice, development of the decidual zone and the surrounding edema after embryonic implantation was defective. This was subsequently accompanied by disintegration of implantation site structure, leading to embryonic death before placentation. Polyploidization, a hallmark of mature decidual cells, was attenuated in DEDD-deficient cells during decidualization. Such inefficient decidualization appeared to be caused by decreased Akt levels, since polyploidization was restored in DEDD-deficient decidual cells by overexpression of Akt. In addition, we showed that DEDD associates with and stabilizes cyclin D3, an important element in polyploidization, and that overexpression of cyclin D3 in DEDD- deficient cells improved polyploidization. These results indicate that DEDD is indispensable for the establishment of an adequate -

Func6onal Profiling from Babelomics 5

Func%onal profiling from Babelomics 5 Dan Crespo [email protected] March 3th, 2016 Where are we? General NGS pipeline: Func9onal analysis: • Single enrichment: Fa9GO • Gene set enrichment: Logisc Model Genomics Transcriptomics Where are we? Func9onal analysis Implemented in: Differenal expression hp://babelomics.org Genes Gene Sets Fa9GO GSA logisc model Ques9ons we try to answer • Is there any significant func%onal enrichment in my gene list / gene sets? Ques9ons we try to answer • Is there any significat func%onal enrichment in my gene list / gene sets? • Are these genes involved in common pathways? Ques9ons we try to answer • Is there any significat func%onal enrichment in my gene list / gene sets? • Are these genes involved in common pathways? • Do they share specific regulaon? Ques9ons we try to answer • Is there any significat func%onal enrichment in my gene list / gene sets? • Are these genes involved in common pathways? • Do they share specific regulaon? • Are they involved in the same disease? Babelomics 5: FaGO Single enrichment Comparison between two list of genes with user defined annotaons Single enrichment Comparison between two list of genes with user defined annotaons List 1: User provided List 2: Func9onal annotaons: • Gene symbols • User provided • Pre-defined annotaons • Probe Ids • Rest of genome • Custom annotaons • Entrez Ids … • Complementary list Mul9ple tesng context Fisher exact test Benjamini – Hochberg p-value correcon Ranked results Single enrichment List 1 List 2 Func9onal annotaons AATF BIRC7 CIAS1 PEA15 ACTA1 DNAI1 KIF3B -

Multiscale Genomic Analysis of The

University of Tennessee Health Science Center UTHSC Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations (ETD) College of Graduate Health Sciences 5-2009 Multiscale Genomic Analysis of the Corticolimbic System: Uncovering the Molecular and Anatomic Substrates of Anxiety-Related Behavior Khyobeni Mozhui University of Tennessee Health Science Center Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations Part of the Mental and Social Health Commons, Nervous System Commons, and the Neurosciences Commons Recommended Citation Mozhui, Khyobeni , "Multiscale Genomic Analysis of the Corticolimbic System: Uncovering the Molecular and Anatomic Substrates of Anxiety-Related Behavior" (2009). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 180. http://dx.doi.org/10.21007/etd.cghs.2009.0219. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Health Sciences at UTHSC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (ETD) by an authorized administrator of UTHSC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multiscale Genomic Analysis of the Corticolimbic System: Uncovering the Molecular and Anatomic Substrates of Anxiety-Related Behavior Document Type Dissertation Degree Name Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Program Anatomy and Neurobiology Research Advisor Robert W. Williams, Ph.D. Committee John D. Boughter, Ph.D. Eldon E. Geisert, Ph.D. Kristin M. Hamre, Ph.D. Jeffery D. Steketee, Ph.D. DOI 10.21007/etd.cghs.2009.0219 This dissertation is available at UTHSC Digital -

Supplementary Tables Table S1 Specificities and Efficiency Scores Of

Supplementary Tables Table S1 Specificities and efficiency scores of sgRNAs targeting the reference gene and the CNS-specific promoters sgRNA Sequence 5‘to 3‘ PAMa Positionb MIT Guide CRISPspec Doench Potential Off -Targets Specificity Score Efficiency For Number of Mismatches Score Score (%) 0 1 2 3 RG1 GCGTTACTTC AGG -258 to -239 82 7.394 86 0 0 0 13 ACTGAAGCAG RG2 TAGAGCAGCA GGG -210 to -191 68 7.464 98 0 0 3 14 AGCTGCACAG RG3 ACTGGGGACT AGG -132 to -112 85 8.321 86 0 0 0 5 GTAGTAAGAC CNS1 AGATAATGAG TGG -69 to -82 89 8.362 63 0 0 0 4 CGAGCCGGGA CNS2 CGCAGAGCGA GGG -34 to -56 83 8.320 94 0 0 0 8 GAGACCGCAG CNS3 CGCACACACG AGG +5 to +24 83 8.030 56 0 0 1 7 CAGCCGGCAC *Protospacer Adjacent Motif; RG1-3, reference gene promoter-specific sgRNAs; CNS1-3, CNS-promoter specific sgRNAs. The MIT specificity and the Doench efficienty scores ranges from 0-100 and summarizes off-target effects into a single number; the higher the number the fewer off target effects are anticipated. The CRISPRspec score represents overall whole genome off-targeting; all scores were in the high range, indicating low off-target predictions (rth.dk/resources/crispr/crisproff); please see main text for additional references. Table S2a Effects of mismatches in sgRNAs targeting the CNS promoter on in silico off-targets sgRNA Potential Locus, Position CNS vs Scrambled* RG vs scrambled* Off-target number CNS 1 2 mismatches 0 3 mismatches 4 Intergenic MIR5095-CTCFL; chr 20:56017262(-) Not in file Not in file Intron ASAP1; chr6:131204007(+) 0.145-fold down, p=0.007 0.353-fold down, p =2.4E-11 Intergenic AK124832-CA10; chr 17:49479286(+) Not in file Not in file Intergenic AKAP7-ARG1; chr 6:131676375(+) n.s.; not in file n.s.; not in file CNS 2 2 mismatches 0 3 mismatches 8 Intergenic LYRM2-ANKRD6;chr 6:90300681(-) n.s.; n.s. -

Death Effector Domain-Containing Proteins DEDD and FLAME-3 Form Nuclear Complexes with the TFIIIC102 Subunit of Human Transcription Factor IIIC

Cell Death and Differentiation (2002) 9, 439 ± 447 ã 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1350-9047/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/cdd Death effector domain-containing proteins DEDD and FLAME-3 form nuclear complexes with the TFIIIC102 subunit of human transcription factor IIIC Y Zhan1,2,3, R Hegde1,2,3, SM Srinivasula1,2,3, Abbreviations: DED, death effector domain; EST, expressed T Fernandes-Alnemri1,2 and ES Alnemri*,1,2 sequence tags; CTD, C-terminal domain 1 Center for Apoptosis Research, Kimmel Cancer Institute, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA Introduction 2 Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Kimmel Cancer Institute, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA Death effector domain (DED)-containing proteins are im- 3 These authors contributed equally to this work portant components of the cell death receptor-signaling * Corresponding author: ES Alnemri, Thomas Jefferson University, Kimmel pathway.1,2 Ligation of the death receptors, such as TNF, Cancer Institute, Bluemle Life Sciences Building, Room 904, 233 S 10th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA. Tel: 215-503-4632; Fax: 215-923-1098; CD95 and TRAIL receptors, results in the recruitment of the E-mail: [email protected] adaptor molecule FADD/Mort-1 through homotypic interac- tions of its C-terminal death domain with the cytoplasmic Received 8.2.02; accepted 8.2.02 death domain of the death receptors.1,3,4 FADD, which also Edited by G Melino contains an N-terminal DED, transduces the activation signal from the death receptors to the DED-containing precursors (procaspases) of the initiator caspases 8 and 10, by direct Abstract interaction of its DED with their corresponding DEDs.1,5 The Death effector domain-containing proteins are involved in association of FADD with procaspase-8 and procaspase-10 important cellular processes such as death-receptor induced results in their auto-processing/activation and the release of apoptosis, NF-kB activation and ERK activation. -

Dissection of a QTL Hotspot on Mouse Distal Chromosome 1 That

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Papers and Publications in Animal Science Animal Science Department 2008 Dissection of a QTL Hotspot on Mouse Distal Chromosome 1 that Modulates Neurobehavioral Phenotypes and Gene Expression Khyobeni Mozhui University of Tennessee Health Science Center Daniel C. Bastiaansen University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Thomas Schikorski University of Tennessee Health Science Center Xusheng Wang University of Tennessee Health Science Center Lu Lu University of Tennessee Health Science Center See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscifacpub Part of the Genetics and Genomics Commons, and the Meat Science Commons Mozhui, Khyobeni; Bastiaansen, Daniel C.; Schikorski, Thomas; Wang, Xusheng; Lu, Lu; and Williams, Robert W., "Dissection of a QTL Hotspot on Mouse Distal Chromosome 1 that Modulates Neurobehavioral Phenotypes and Gene Expression" (2008). Faculty Papers and Publications in Animal Science. 936. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscifacpub/936 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Animal Science Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Papers and Publications in Animal Science by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Khyobeni Mozhui, Daniel C. Bastiaansen, Thomas Schikorski, Xusheng Wang, Lu Lu, and Robert W. Williams This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/animalscifacpub/936 Dissection of a QTL Hotspot on Mouse Distal Chromosome 1 that Modulates Neurobehavioral Phenotypes and Gene Expression Khyobeni Mozhui, Daniel C. Ciobanu, Thomas Schikorski, Xusheng Wang, Lu Lu, Robert W.