Chapter 4: Case Study Oberhausen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Go to Oberhausen! Some Notes on an Online Film Festival Experience

KEIDL MELAMED HEDIGER SOMAINI PANDEMIC MEDIA MEDIA OF FILM OF FILM CONFIGURATIONS CONFIGURATIONS Pandemic Media Configurations of Film Series Editorial Board Nicholas Baer (University of Groningen) Hongwei Thorn Chen (Tulane University) Miriam de Rosa (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice) Anja Dreschke (University of Düsseldorf) Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan (King’s College London) Andrea Gyenge (University of Minnesota) Jihoon Kim (Chung Ang University) Laliv Melamed (Goethe University) Kalani Michell (UCLA) Debashree Mukherjee (Columbia University) Ara Osterweil (McGill University) Petr Szczepanik (Charles University Prague) Pandemic Media: Preliminary Notes Toward an Inventory edited by Philipp Dominik Keidl, Laliv Melamed, Vinzenz Hediger, and Antonio Somaini Bibliographical Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie(GermanNationalBibliography);detailed bibliographic information is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Publishedin2020bymesonpress,Lüneburg,Germany with generous support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft www.meson.press Designconcept:TorstenKöchlin,SilkeKrieg Cover design: Mathias Bär Coverimage:©Antoined’Agata,reprintedwithpermissionfromtheartist Editorial assistance: Fabian Wessels TheprinteditionofthisbookisprintedbyLightningSource, MiltonKeynes,UnitedKingdom ISBN(Print):978-3-95796-008-5 ISBN(PDF): 978-3-95796-009-2 DOI:10.14619/0085 The PDF edition of this publication can -

RB PD Str. - Nr

Strecke Strecke Freigabe Freigabe RB PD Str. - Nr. Streckenbezeichnung km-Anfang km-Ende km-Anfang km-Ende Nord Kiel 1043 Neumünster, W 23 - Bad Oldesloe, W 22 74,4 + 27 119,8 + 66 74,4 + 27 75,3 + 20 Nord Kiel 1043 Neumünster, W 23 - Bad Oldesloe, W 22 74,4 + 27 119,8 + 66 78,5 + 0 119,8 + 66 Ost Schwerin 1122 Lübeck Hbf, 90W108 - Strasburg (Uckerm), W 48 0,4 + 84 234,1 + 48 58,6 + 55 129,4 + 54 Nord Hamburg 1153 Lüneburg, W 210 - Stelle, W 5 132,9 + 42 157,8 + 75 132,9 + 42 157,8 + 75 Nord Hamburg 1250 Abzw Hamburg Oberhafen, W 4330 - Hamburg Hbf, W 442 352,4 + 56 355,5 + 64 353,5 + 85 355,5 + 64 Nord Bremen 1283 Rotenburg (Wümme), W 12 - Buchholz (Nordh.),W 261 (Mittelgleis) 280,8 + 67 323,4 + 76 280,8 + 67 296,0 + 0 Nord Hamburg 1283 Rotenburg (Wümme), W 12 - Buchholz (Nordh.),W 261 (Mittelgleis) 280,8 + 67 323,4 + 76 296,0 + 0 323,4 + 76 Nord Hamburg 1291 Hamburg-Rothenburgsort, W 123 - Abzw Hamburg Ericus, W 712 282,0 + 11 284,9 + 30 282,0 + 11 284,9 + 30 Nord Bremen 1500 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf - Bremen Hbf, W 110 0,0 + 0 45,1 + 87 0,0 + 0 45,1 + 87 Nord Bremen 1520 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf, W 5 - Leer (Ostfriesl), W 38 0,8 + 42 55,5 + 12 0,8 + 42 55,5 + 12 Nord Bremen 1522 Oldenburg (Oldb) Hbf - Wilhelmshaven 0,0 + 0 52,3 + 59 0,0 + 0 52,3 + 59 Nord Bremen 1570 Emden Rbf --(Norden)-- - Jever 0,0 + 0 81,0 + 8 0,0 + 0 31,0 + 45 Nord Bremen 1570 Emden Rbf --(Norden)-- - Jever 0,0 + 0 81,0 + 8 60,5 + 80 81,0 + 8 Nord Bremen 1574 Norden, W 35 - Norddeich Mole 30,9 + 41 36,6 + 49 30,9 + 41 36,6 + 49 Nord Osnabrück 1600 Osnabrück Hbf Po, W -

Liste Der Jungmeister 2018

Jungmeister*innen 2018 Handwerk Name Vorname Ort Landkreis Bäcker Beha Andreas Titisee-Neustadt Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Bäcker Schütz Michael St. Peter Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Brunn Tino Heuweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Eckerle Markus Oberried Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Felice Fabio Gundelfingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Frey Rainer Badenweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Graf Daniel Müllheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Helm Kevin Buggingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Kathan Michael Artur March-Holzhausen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Kraus Witali Merdingen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Ruh Marius Pfaffenweiler Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schmidt Adrian Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schmidt Manuel Breisach Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Schwär Hannes Titisee-Neustadt Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Elektrotechniker Wiegand Oleg Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Deger Christian Neuenburg Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Knörr Lukas Ehrenstetten Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Feinwerkmechaniker Wetzel Marvin Müllheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Andresen Juliane Bad Krozingen-Biengen Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Bergsma Julia Patricia Neuenburg am Rhein Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Jaekel Lisa Lenzkirch Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Friseur Philipp Selina Heitersheim Breisgau Hochschwarzwald Holzbildhauer Acar Joana Ilayda Merzhausen -

Implementing Innovative Hotel Solutions. We Know How. Geographic Distribution of Hotel Portfolio*

Implementing innovative hotel solutions. We know how. Geographic distribution of hotel portfolio* Belgium Netherlands Valuation in EUR m: 122.5 Valuation in EUR m: 190.8 Properties: 2 Properties: 3 Germany Valuation in EUR m: 3,682.0 Properties: 41 USA UK Valuation in EUR m: 926.4 Valuation in EUR m: 179.6 Properties: 7 Properties: 4 Poland Valuation in EUR m: 173.6 France Properties: 5 Valuation in EUR m: 168.3 Properties: 2 Austria Valuation in EUR m: 119.4 Properties: 5 Spain Valuation in EUR m: 46.5 Properties: 1 * In the case of mixed-use properties the full value in accordance with investment law accounting requirements has been disclosed; number of properties excl. separate sites, incl. multiple occupancy for sites with more than one hotel brand. 2 “We have a broadly diversified hotel portfolio, which we aim to expand further both in Europe and beyond. Our partnership-based investment approach, combined with our strong hospitality expertise, gives us the ability to complete even complex transactions reliably.” Andreas Löcher Head of Investment Management Hospitality, Union Investment 3 Committed to growth We have been investing in hotels for over 45 years. We stand out through our combination of hotel sector and property industry expertise, allowing us to become one of the leading European investment managers for hotel real estate. Union Investment is one of the largest real estate Portland and Seattle, we have a presence in many Hotel transaction volume 2013 – Q2 / 2019 investment managers in Europe, with 368 com- gateway cities as well as in dynamic secondary (EUR m) mercial properties and real estate assets under locations. -

SV Lippstadt 08 1:1 SV Rödinghausen Rot-Weiß Oberhausen Sonntag, 11.08.19 5

NULLNEUNER MatchDay Dienstag, 20.08. | 19:30 Uhr WIR BEGRÜSSEN 03. Spieltag | Saison 19/20 DEN SV RÖDINGHAUSEN 1970 UND ROT-WEISS OBERHAUSEN Samstag, 24.08. | 14:00 Uhr 05. Spieltag | Saison 19/20 IN DER BELKAW ARENA! Der MatchDay wird präsentiert von: Unser Kader 2019/20 SpieltagInfo Regionalliga West Regionalliga West Mit defensiver Stabilität und Kompaktheit gegen TOR 01 44 71 04 05 12 14 20 21 22 ABWEHR die Top-Teams Rödinghausen und Oberhausen Michael Cebulla Justin Landwehr Peter Stümer Andy Habl Tom Isecke Zachary-Oduro Bonsu Oktay Dal Claudio Heider Milo McCormick Daniel Spiegel 32 Jahre 18 Jahre 21 Jahre 34 Jahre 21 Jahre 20 Jahre 23 Jahre 23 Jahre 25 Jahre 22 Jahre 0 Einsätze 0 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 2 Einsätze 1 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 1 Einsätze 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore Nach dem ersten Regionalliga-Sieg bei der SG Wattenscheid 09 ist ener erst letzte Woche im DFB-Pokal, als sie dem Bundesligisten SC vor dem Knaller-Doppelpack gegen den SV Rödinghausen (Diens- Paderborn nach 120 Minuten ein 3:3 abrangen. Erst im Elfmeter- tag, 19.30 Uhr) und Rot-Weiß Oberhausen (Samstag, 14 Uhr) in der schießen kam der K.o. gegen die Erstliga-Mannschaft. 06 07 08 09 10 11 15 17 18 23 25 BELKAW Arena. Beide Mannschaften zählen zu den Topteams der Cenk Durgun Daniel Isken Yoshua Grazina Baris Sarikaya Ajet Shabani Patrick Hill David Mamutovic Etienne Kamm Dustin Zahnen Jens Bauer Mo Dahas MITTELFELD 27 Jahre 24 Jahre 21 Jahre 23 Jahre 27 Jahre 23 Jahre 18 Jahre 22 Jahre 23 Jahre 22 Jahre 24 Jahre Liga und treten sicherlich favorisiert beim SV Bergisch Gladbach 09 Personell bangen die 09er am Flügelstürmer Baris Sarikaya, der 3 Einsätze 0 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 1 Einsätze 1 Einsätze 3 Einsätze 0 Einsätze 0 Einsätze 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 0 Tore 1 Tor 0 Tore 0 Tore an. -

Investment Locations Germany 2019 Residential – Rents and Yields

Investment locations Germany 2019 Residential – rents and yields The situation on the German housing markets is a reflection of social changes and economic consequences. All in all, a high center-focused and demand-based development can be seen, while at the same time the heterogeneity of supply is increasing. Urbanity and the desire to live in cities result in a different price ratio. The scarcity of supply is increasingly being countered by means of post-consolidation measures and neighbourhood development. The view outside the conurbations is different: less the lack of building land than emigration shapes these housing markets. Kiel 7.85 10.50 4.40 Rostock 7.13 10.56 4.50 Lübeck 8.01 10.21 4.60 Schwerin 7.09 Hamburg 8.58 12.00 Lüneburg 5.50 16.29 2.70 8.99 11.05 Oldenburg 4.30 8.08 10.16 Bremen 4.30 9.06 11.66 4.70 10.13 17.00 2.40 8.67 8.52 Berlin 11.31 11.23 7.76 4.10 4.90 9.76 Hanover Wolfsburg Potsdam 4.90 Osnabrück Reckling- 9.84 Braunschweig 12.16 hausen Hildesheim 10.07 7.02 3.80 5.79 9.14 7.90 12.72 6.40 10.21 Magdeburg 7.42 3.80 4.50 6.20 8.20 4.90 5.97 Bielefeld 5.30 Herne Münster 7.77 6.95 Detmold 6.23 5.30 6.03 6.08 7.91 7.77 10.75 Gütersloh Cottbus 4.70 7.27 6.00 5.60 7.00 6.34 Paderborn 8.73 7.26 6.04 Oberhausen 7.70 8.92 11.10 6.46 6.00 7.43 Göttingen 4.90 7.49 5.00 9.39 6.80 5.97 8.73 5.30 4.90 8.18 Hamm 7.19 5.70 Bochum Dortmund 9.74 7.74 6.84 Duisburg 4.70 9.43 8.74 Essen 6.37 Ratingen 5.00 Leipzig 5.30 Krefeld Wuppertal 8.11 5.30 Kassel 7.37 Remscheid Mönchen- 10.49 Dusseldorf Dusseldorf 6.05 3.60 gladbach Solingen -

Last Hour Logistics

In cooperation with DO AMAZING THINGS WITH DATA Marketing Material* November 2019 Research Report LAST HOUR LOGISTICS The brand DWS represents DWS Group GmbH & Co. KGaA and any of its subsidiaries, such as DWS Distributors, Inc., which offers investment products, or DWS Investment Management Americas Inc. and RREEF America L.L.C., which offer advisory services. There may be references in this document which do not yet reflect the DWS Brand. Please note certain information in this presentation constitutes forward-looking statements. Due to various risks, uncertainties and assumptions made in our analysis, actual events or results or the actual performance of the markets covered by this presentation report may differ materially from those described. The information herein reflects our current views only, is subject to change, and is not intended to be promissory or relied upon by the reader. There can be no certainty that events will turn out as we have opined herein. For Professional Clients (MiFID Directive 2014/65/EU Annex II) only. For Qualified Investors (Art. 10 Para. 3 of the Swiss Federal Collective Investment Schemes Act (CISA)). For Qualified Clients (Israeli Regulation of Investment Advice, Investment Marketing and Portfolio Management Law 5755-1995). Outside the U.S. for Institutional investors only. In the United States and Canada, for institutional client and registered representative use only. Not for retail distribution. Further distribution of this material is strictly prohibited. In Australia, for professional investors only. *For investors in Bermuda: This is not an offering of securities or interests in any product. Such securities may be offered or sold in Bermuda only in compliance with the provisions of the Investment Business Act of 2003 of Bermuda which regulates the sale of securities in Bermuda. -

Deutscher Städte-Vergleich Eine Koordinierte Bürgerbefragung Zur Lebensqualität in Deutschen Und Europäischen Städten*

Statistisches Monatsheft Baden-Württemberg 1/2008 Land, Kommunen Deutscher Städte-Vergleich Eine koordinierte Bürgerbefragung zur Lebensqualität in deutschen und europäischen Städten* Ulrike Schönfeld-Nastoll Die amtliche Landesstatistik untersucht Sach- nun vor und erste Ergebnisse wurden auf der verhalte und deren Veränderungen – auch für Statistischen Frühjahrstagung in Gera im März Kommunen. Sie untersucht grundsätzlich 2007 dem Fachpublikum vorgestellt. aber nicht die subjektiven Meinungen der Bürgerinnen und Bürger zu den festgestellten Erstmals ist es nun möglich, die Umfrageergeb- Sachverhalten und den Veränderungen. Das nisse der deutschen Städte miteinander zu ver- überlässt sie Demoskopen und in zunehmen- gleichen. Darüber hinaus besteht auch die Mög- dem Maße der Kommunalstatistik. Gerade die lichkeit, aus der EU-Befragung Ergebnisse der kommunalstatistischen Ämter und Dienst- anderen europäischen Städte gegenüberzu- Dipl.-Soziologin Ulrike stellen haben auf diesem Untersuchungsfeld stellen. Schönfeld-Nastoll ist einen eindeutigen Vorsprung gegenüber der Bereichsleiterin für Statistik und Wahlen der Stadt Landesstatistik. Kommunalstatistiker haben Oberhausen. das Ohr näher am Puls der Zeit und des Der EU-Fragenkatalog der Bürgerbefragung Ortes. Insgesamt wurden 23 Fragen zu drei Themen- Da in demokratisch orientierten Gesellschaften komplexen gestellt. * Ein Projekt der Städtege- die kollektiven Meinungen der Bürgerinnen meinschaft Urban Audit 1 n und des Verbands Deut- und Bürger für Entscheider und Parlamente Im ersten Komplex wurde die Zufriedenheit scher Städtestatistiker von großer Bedeutung sein können, haben mit der städtischen Infrastruktur und den (VDST). sich etwa 300 europäische Städte, darunter 40 deutsche, für ein Urban Audit entschieden. Dieses entwickelt sich zu einer europaweiten Datensammlung zur städtischen Lebensquali- S1 „Sie sind zufrieden in ... zu wohnen“ tät. Dazu werden 340 statistische Merkmale aus allen Lebensbereichen auf Gesamtstadt- ebene erhoben. -

List of Participating Centers

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA List of participating centers Aachen – Innere RWTH; Aachen – Uni-Kinderklinik RWTH; Aalen Kinderklinik; Ahlen St. Franziskus Kinderklinik; Aidlingen Praxisgemeinschaft; Altötting Zentrum Inn-Salzach; Altötting-Burghausen Innere Medizin; Amstetten Klinikum Mostviertel Kinderklinik; Arnsberg-Hüsten Karolinenhospital Kinderabteilung; Asbach Kamillus-Klinik Innere; Aue Helios Kinderklink; Augsburg Innere; Augsburg Kinderklinik Zentralklinikum; Aurich Kinderklinik; Bad Aibling Internistische Praxis; Bad Driburg / Bad Hermannsborn Innere; Bad Hersfeld Innere; Bad Hersfeld Kinderklinik; Bad Kreuznach-St. Marienwörth-Innere; Bad Kreuznach-Viktoriastift; Bad Krozingen Klinik Lazariterhof Park-Klinikum; Bad Kösen Kinder-Rehaklinik; Bad Lauterberg Diabeteszentrum Innere; Bad Mergentheim – Diabetesfachklinik; Bad Mergentheim – Gemeinschaftspraxis DM-dorf Althausen; Bad Oeynhausen Herz-und Diabeteszentrum NRW; Bad Orb Spessart Klinik; Bad Orb Spessart Klinik Reha; Bad Reichenhall Kreisklinik Innere Medizin; Bad Salzungen Kinderklinik; Bad Säckingen Hochrheinklinik Innere; Bad Waldsee Kinderarztpraxis; Bautzen Oberlausitz KK; Bayreuth Innere Medizin; Berchtesgaden CJD; Berchtesgaden MVZ Innere Medizin; Berlin DRK-Kliniken; Berlin Endokrinologikum; Berlin Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth; Berlin Klinik St. Hedwig Innere; Berlin Lichtenberg – Kinderklinik; Berlin Oskar Zieten Krankenhaus Innere; Berlin Parkklinik Weissensee; Berlin Schlosspark-Klinik Innere; Berlin St. Josephskrankenhaus Innere; Berlin Virchow-Kinderklinik; -

Fahrplan-Info Ruhrort-Bahn

Fahrplan ab 09.12.2018 Fahrplan 2019 RB 36 Montag bis Freitag RB 36 Duisburg-Ruhrort › Oberhausen Hbf RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 Verkehrstage Montag bis Freitag Ruhrort-Bahn Duisburg-Ruhrort ab 00:16 04:46 halbstündlich 20:16 stündlich 23:16 Duisburg-Meiderich Süd ab 00:20 04:50 halbstündlich 20:20 stündlich 23:20 Duisburg-Meiderich Ost ab 00:23 04:53 halbstündlich 20:23 stündlich 23:23 Duisburg-Obermeiderich ab 00:25 04:55 halbstündlich 20:25 stündlich 23:25 Oberhausen Hbf an 00:28 04:58 halbstündlich 20:28 stündlich 23:28 Duisburg-Ruhrort Oberhausen Hbf Samstag und Sonntag und Feiertag RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 RB 36 Gültig ab 09.12.2018 ab Gültig Verkehrstage Samstag Sonntag Feiertag Duisburg-Ruhrort ab 00:16 06:16 07:16 stündlich 23:16 Duisburg-Meiderich Süd ab 00:20 06:20 07:20 stündlich 23:20 Duisburg-Meiderich Ost ab 00:23 06:23 07:23 stündlich 23:23 Duisburg-Obermeiderich ab 00:25 06:25 07:25 stündlich 23:25 Oberhausen Hbf an 00:28 06:28 07:28 stündlich 23:28 Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr Fahrplan-Info Unterwegs im Auftrag von: Sonderregelungen Feiertage NRW 2018/2019 RB 36 „Ruhrort-Bahn“ Di 25., Mi 26. Dezember 2018 Weihnachten | Di 1. Januar 24. und 31. Dezember 2018 Heiligabend und 2019 Neujahr | Fr 19. April Karfreitag | So 21., Mo 22. April Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr Silvester verkehren die Züge wie an Samstagen. Ostern | Mi 1. Mai Tag der Arbeit | Do 30. -

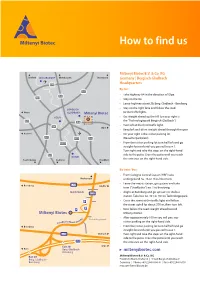

How to Find Us

How to find us Miltenyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG Krefeld DÜSSELDORF Oberhausen Dortmund Germany | Bergisch Gladbach A 46 Headquarters By car: A 1 • Take highway A4 in the direction of Olpe. A 3 A 57 • Stay on the A4. • Leave highway at exit 20, Berg. Gladbach - Bensberg. • Stay on the right lane and follow the road BERGISCH Venlo GLADBACH Miltenyi Biotec to the traffic lights. KÖLN • Go straight ahead up the hill (on your right is A 61 the “Technologiepark Bergisch Gladbach”). A 4 • Turn left at the third traffic light. A 4 Olpe • Keep left and drive straight ahead through the gate. Aachen • On your right is the visitor parking lot A 1 A 59 A 3 (Besucherparkplatz). A 555 • From the visitor parking lot turn half left and go straight forward until you passed house 1. Turn right and take the steps on the right-hand A 61 side to the patio. Cross the patio until you reach BONN Saarbrücken Koblenz Frankfurt the entrance on the right-hand side. By train / bus: • From Cologne Central Station (HBF) take Herkenrath underground no. 16 or 18 to Neumarkt. • Leave the metro station, go upstairs and take Bensberg L 298 Lindlar tram (“Stadtbahn“) no. 1 to Bensberg. MOITZFELD L 195 • Alight at Bensberg and go upstairs to the bus station. Take bus no. 421 or 454 to Technologiepark. P • Cross the street at the traffic light and follow the street uphill for about 200 m, then turn left. P P • Now follow the road straight ahead toward Miltenyi Biotec Miltenyi Biotec. -

Germeisterin Und

Öffentliche Bekanntmachung Zugelassene Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl des/der Oberbürgermeisters/Oberbür- germeisterin und der Vertretung der Stadt Oberhausen sowie der Bezirksvertretun- gen Alt-Oberhausen, Sterkrade und Osterfeld in der Stadt Oberhausen am 13.09.2020 Nach §§ 19, 46 b des Kommunalwahlgesetzes (KWahlG)in Verbindung mit § 11 des Gesetzes zur Durchfüh- rung der Kommunalwahlen 2020 in Verbindung mit §§ 75b Abs. 7, 30, 31 Abs. 4, 72 Abs. 7 der Kommunal- wahlordnung (KWahlO) gebe ich bekannt, dass der Wahlausschuss in seiner Sitzung am 03.08.2020 folgende Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl des/der Oberbürgermeisters/Oberbürgermeisterin und der Vertretung der Stadt Oberhausen sowie der Bezirksvertretungen Alt-Oberhausen, Sterkrade und Osterfeld in der Stadt Oberhausen zugelassen hat: A. Wahlvorschläge für das Amt der Oberbürgermeisterin/des Oberbürgermeisters Wahl- Name Beruf Geburtsjahr, PLZ, Wohnort Partei / Wählergruppe vor- E-Mail / Postfach Geburtsort schl. Nr. 1 Berg, Thorsten Bankkaufmann 1969, 46049 Oberhausen Sozialdemokratische Partei [email protected] / - Gelsenkir- Deutschlands (SPD) chen 2 Schranz, Daniel Oberbürgermeister, Magister 1974, 46117 Oberhausen Christlich Demokratische [email protected] / - Artium Oberhausen Union Deutschlands (CDU) 4 Axt, Norbert Emil Lehrer 1958, 46147 Oberhausen BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN [email protected] / - Hünfeld (GRÜNE) 5 Carstensen, Jens Sozialarbeiter 1958, 46149 Oberhausen DIE LINKE (DIE LINKE) [email protected] / - Oberhausen 7 Wädlich, Claudia Schriftstellerin 1958, 46047 Oberhausen Die Violetten - für spirituelle [email protected] / - Oberhausen Politik (DIE VIOLETTEN) 8 Kempkes, Wolfgang Betriebswirt 1966, 46049 Oberhausen Alternative für Deutschland [email protected] / - Oberhausen (AfD) 9 Dr. Mülhausen, Urban Laurentius Maria Arzt i. R. 1959, 46045 Oberhausen Offen für Bürger (OfB) [email protected] / - Weiden jetzt Köln B.