Early Weaving in New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

![The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green [Electronic Resource]: an Oxford](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8596/the-adventures-of-mr-verdant-green-electronic-resource-an-oxford-458596.webp)

The Adventures of Mr. Verdant Green [Electronic Resource]: an Oxford

. SjHasajj;--: (&1&MF 1 THE VENTURES tw MM **> 'SkSSi *"3 riLLlAM PATEiiSGN, EDINBURGH Um LOKLOj , . fJ tl^OTWltiBttt y :! THE ADVENTURES OF MR. VERDANT GREEN. : ic&m MMwmmili¥SlW-ia^©IMS OF yVLiMR. Verbint ^Tf BY CUTHBERT BEDE, B.A., WITH HalaUSTHANIONS 38 Y THE AUTHOR, LONDON JAMES BLACKWOOD & CO., LOVELL'S COURT, PATERNOSTER ROW. : — THE ADVENTURES MR. VERDANT GREEN, %n (f^forb Jfwsjimatr. BY CUTHBERT BEDE, B.A. ttlj ^ximcrouS iFIludtrattond DESIGNED AND DRAWN ON THE WOOD BY THE AUTHOR. —XX— ' A COLLEGE JOKE TO CURE THE DUMPS.' SlUlft. ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SIXTH THOUSAND. LONDON JAMES BLACKWOOD & CO., LOVELL'S COURT, PATERNOSTER ROW. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PACE Mr. Verdant Green's Relatives and Antecedents .... I CHAPTER II. Mr. Verdant Green is to be an Oxford-man y CHAPTER III. Mr. Verdant Green leaves the Home of his Ancestors ... 13 CHAPTER IV. Mr. Verdant Green becomes an Oxford Undergraduate . .24. CHAPTER V. Mr. Verdant Green matriculates, and makes a sensation . .31 CHAPTER VI. Mr. Verdant Green dines, breakfasts, and goes to Chapel . .40 CHAPTER VII. " Mr. Verdant Green calls on a Gentleman who is licensed to sell " . 49 CHAPTER VIII. Mr. Verdant Green's Morning Reflections are not so pleasant as his Evening Diversions 58 vi Contents. CHAPTER IX. ,AGE Mr. Verdant Green attends Lectures, and, in despite of Sermons, has dealings with Filthy Lucre 67 CHAPTER X. Mr. Verdant Green reforms his Tailors' Bills and runs v^ "'h°rs. He also appears in a rapid act of Horsemanship, and i.-Js Isis cool in Summer 73 CHAPTER XI. -

Fabric”? Find 20 Synonyms and 30 Related Words for “Fabric” in This Overview

Need another word that means the same as “fabric”? Find 20 synonyms and 30 related words for “fabric” in this overview. Table Of Contents: Fabric as a Noun Definitions of "Fabric" as a noun Synonyms of "Fabric" as a noun (20 Words) Usage Examples of "Fabric" as a noun Associations of "Fabric" (30 Words) The synonyms of “Fabric” are: cloth, material, textile, framework, stuff, tissue, web, structure, frame, form, make-up, constitution, composition, construction, organization, infrastructure, foundations, mechanisms, anatomy, essence Fabric as a Noun Definitions of "Fabric" as a noun According to the Oxford Dictionary of English, “fabric” as a noun can have the following definitions: The underlying structure. The body of a car or aircraft. The basic structure of a society, culture, activity, etc. Cloth or other material produced by weaving or knitting fibres. Artifact made by weaving or felting or knitting or crocheting natural or synthetic fibers. The walls, floor, and roof of a building. GrammarTOP.com Synonyms of "Fabric" as a noun (20 Words) The branch of science concerned with the bodily structure of humans, animals, and other living organisms, especially as revealed by dissection anatomy and the separation of parts. Human anatomy. A piece of cloth for cleaning or covering something e g a dishcloth or a cloth tablecloth. A cloth bag. A musical work that has been created. composition The social composition of villages. The constitution written at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia constitution in 1787 and subsequently ratified by the original thirteen states. The constitution of a police authority. GrammarTOP.com The action of building something, typically a large structure. -

Congressional Record-Sen Ate

8718 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE. SEPTEJ\IBER 19, from the files of the House1 without leaving copies, papers in the case We, therefore, think there is no merit in the proposition, and that of J. W. Chickering. it ought to be inde1initely postponed. LEA-VE OF ABSENCE. The renort was agreed to, and the joint resolution indefinitely post poned. 1\Ir. Fmm,. by unanimous consent, obtained indefinite leave of ab Mr. P ALUER, from the Committee on Commerce, reported an sence, on account of important business. amendment intended to be proposed to the ~eneral deficiency appro 'Ihe hour of 5 o'clock having arrived, the House, in accordance with priation bill; whi<'h was referred to the Committee on Appropriations. its standing order, adjourned. Mr. WILSON, of Maryland, from the Committee on Claims,. to whom were referred the following bills, reported them severally without PRIVATE BILLS INTRODUCED AND REFERRED. amendment, and submitted renorts thereon: · UndEJr the rnle private bills of the following titles were introduced A bill (H. R. 341) for the relief of John Farley; and and referred· as indicated below: A bill (S. 729) for the relief of J. A. Henry and others. By Mr. BLAND (by request): A bill (H. R. 11456) to pay Philip Mr. CHANDLER, fn>m the Select Committee on fud~an Traders, to Henke.Lfor property unlawfully confucateci and destroyed-to the Com whom was referred the bill (S. 3522) regulating th~ purchase of timber mittee on War Claims. from. Indians, reported it with an amendment.. l:y Air. BUTLEH.: A bill (H. R. -

Fine Golf Books & Memorabilia

Sale 486 Thursday, August 16, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Golf Books & Memorabilia Auction Preview Tuesday, August 14, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, August 15, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, August 16, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Appendix 6-3

APPENDIX 9.3 REFERENCES MADE TO FABRICS AND CLOTHING BY K.T. KHLEBNIKOV (Compiled by Margan Allyn Grover, from Khlebnikov 1994) 322 REFERENCES MADE TO FABRICS AND CLOTHING BY K.T. KHLEBNIKOV Compiled by Margan Allyn Grover from K.T. Khlebnikov (1994) When and at What Price Goods Were Purchased from Foreigners: Frieze, 150 yards, 1805 - 2 piasters 14 cents, 1808 – 4p, 1810 – 20p, 1811 – 2p Blue nankeen, 100 funts, 1808 – 1p 50c, 1811 – 2p Large blanket, piece, 1808 – 3p 50c, 1811 – 2p (from Khlebnikov 1994: 20, Table 2) Goods traded by Mr Ebbets in Canton under contract with Mr Baranov: 4,000 pieces of nankeen – at 90 centimes 2,000 pieces of blue nankeen – at 1 piaster 20 cents 800 pieces of flesh-colored nankeen – at 90 cents 300 pieces of black nankeen – at 2p 75c 200 pieces fustian – at 2p 75c 600 pieces of cotton – at 6p 50c 10 piculs velvet – at 28p 250 pieces of demi-cotton - at 1p 50c 10 piculs of thread – at 100p 55 pieces of seersucker – at 4p 595 silk waistcoats for 840p 500 pieces of silk material – at 9.20p (from Khlebnikov 1994: 21-23) Goods Issued in Sitkha to Mr O’Cain and Exchange of Same in Canton, 1806: 500 pieces of silk material, 6p 85c 200 pieces of silk material, 5p 147 pieces of satin, 20p 25c 50 packets of handkerchiefs, 9p 75c 70 pieces of satin, from 18p to 19p 150 pieces of satin, 16p 50c 30 pieces of taffetta, 12p 75c 28 catties of silk, 6p 50c 5 pieces of camelot, 26p Mr Baranov continued to figure the piaster at the exchange rate of two rubles throughout his administration. -

The Textile Museum Thesaurus

The Textile Museum Thesaurus Edited by Cecilia Gunzburger TM logo The Textile Museum Washington, DC This publication and the work represented herein were made possible by the Cotsen Family Foundation. Indexed by Lydia Fraser Designed by Chaves Design Printed by McArdle Printing Company, Inc. Cover image: Copyright © 2005 The Textile Museum All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means -- electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise -- without the express written permission of The Textile Museum. ISBN 0-87405-028-6 The Textile Museum 2320 S Street NW Washington DC 20008 www.textilemuseum.org Table of Contents Acknowledgements....................................................................................... v Introduction ..................................................................................................vii How to Use this Document.........................................................................xiii Hierarchy Overview ....................................................................................... 1 Object Hierarchy............................................................................................ 3 Material Hierarchy ....................................................................................... 47 Structure Hierarchy ..................................................................................... 55 Technique Hierarchy .................................................................................. -

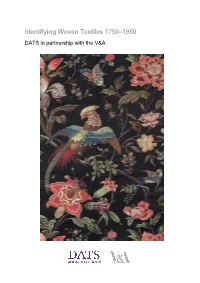

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750-1950 Identification

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A 1 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 This information pack has been produced to accompany two one-day workshops taught by Katy Wigley (Director, School of Textiles) and Mary Schoeser (Hon. V&A Senior Research Fellow), held at the V&A Clothworkers’ Centre on 19 April and 17 May 2018. The workshops are produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying woven textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the wider public and is also intended as a stand-alone guide for basic weave identification. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740–1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identifying Fibres and Fabrics Identifying Handmade Lace Front Cover: Lamy et Giraud, Brocaded silk cannetille (detail), 1878. This Lyonnais firm won a silver gilt medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle with a silk of this design, probably by Eugene Prelle, their chief designer. Its impact partly derives from the textures within the many-coloured brocaded areas and the markedly twilled cannetille ground. Courtesy Francesca Galloway. 2 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Tips for Dating 4 3. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

Wool and Water – an Enduring Partnership in Exmoor and the Surrounding Area

Wool and Water – an enduring partnership in Exmoor and the surrounding area. By DWLCT Academic Associate Lindy Head Lindy runs a wool company on behalf of the Exmoor Horn Sheep Breeders’ Society – www.exmoorhornwool.co.uk An overview In this modern era, we are familiar with the concept of electric power generated by water. Our predecessors were no less ingenious when they used waterpower more directly as the energy source in industrial processes such as milling, metal working, wool processing and paper production. Even the most forward-looking current plans for wave power have their precursor in tide mills. A leat, which is a Westcountry term for a mill stream, is a man-made water channel diverting water (usually from a river), which enables a factory or mill owner to easily control the volume and rate of flow of water to machinery. At a more rudimentary level, earth-bank leats are still used in field systems to control seasonal flow of irrigation and mediaeval farmers knew of the benefits to grass growth in flooding water meadows every spring. There is evidence that Dulverton Leat was used to irrigate the area now forming the caravan park with some of the caravan pitches still prone to becoming muddy. Coupled with water as a source of power is of course the use of water for transport. Exmoor and the surrounding area was served by the ports of Dunster (until it silted up in the fifteenth century), Minehead and Bridgwater to the north and Exeter to the south, were all involved in woollen trading to the near continent. -

Army Women in July of 1775, the Continental Congress Passed a Resolution to Form an Army Hospital Corps

Army Women In July of 1775, the Continental Congress passed a resolution to form an army hospital corps. This was to include one nurse for every ten men. Though it does not state that these nurses are to be female, it seems to be common practice throughout the war to employ women where possible. Assigning nursing duty to men necessitated taking able bodies away from the front lines. The Connecticut soldiers at Ticonderoga in the late fall of 1775 were both sick and homesick. They had returned to New York from Canada and were waiting out the last month of their enlistments. Writing from the Fort on November 20th, General Phillip Schuyler described their eagerness to depart the Northern Army in a letter to the Continental Congress. Our Army in Canada is daily reducing; about three hundred of the troops, raised in Connecticut, having passed here within a few days; so that I believe not more than six hundred and fifty or seven hundred, from that Colony, are left. From the different New- York Regiments, about forty are also come away. An unhappy home-sickness prevails. Those mentioned above all came down invalids; not one willing to re-engage for the winter service, and unable to get any work done by them, I discharged them, en groupe. Of all the specificks ever invented for any, there is none so efficacious as a discharge for this prevailing disorder. No sooner was it administered, but it perfected the cure of nine out of ten, who, refusing to wait for boats to go by the way of Fort George, slung their heavy packs, crossed the lake at this place, and undertook a march of two hundred miles with the greatest good-will and alacrity. -

Fabric & Leather

Steelcase x Bolia FY21 – NORTH AMERICA | Latest update: September 2020 PILLING PRICE MATERIAL / CARE RECOMMEN- MARTIN- LIGHT RESI- TESTS & CERTIFICATIONS GROUP FIBRE CONTENT DATION DALE FASTNESS Fabric & Leather STANCE 98% Recycled STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® Bergo 3 Polyester 100.000 7 5 EU Ecolabel 2% Polyester CAL TB 117 FABRIC Beige Dark Blue Grey Light Light Grey Petrol Raw Brown Amber STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® TEST Baize 3 100% Polyester 78.000 5 4 - 5 CAL TB 117 BS 5852 Source 0 + 1 FABRIC Anthracite Dark Grey Dust Blue Dust Green Grey Light Grey Sand TEST TEST TEST TEST TEST TEST EN 1021-1 STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® London 4 100% Polyester 100.000 5 4 – 5 CAL TB 117 BS 5852 Source 0 + 1 FABRIC Blue Brown Burgundy Dark Grey Dust Blue Dust Green Grey Light Beige Light Blue Light Grey Mint Multi Grey Petrol Raw Rosa Sea Green EN 1021-1 Brown Amber 56% Acrylic STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® 30% Polyester Memory 4 7% Viscose 40.000 5 4 - 5 CAL TB 117 5% Linen BS 5852 Source 0 + 1 FABRIC Anthracite Blue Grey / Grey Light Light Grey EN 1021-1 White Brown 2% Cotton Qual STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® 4 100% Wool 76.000 5 4 CAL TB 117 BS 5852 Source 0 + 1 WOOL Army Curry Dark Grey Grey Light Grey Mint Navy Rose Sand Sea Green Stone Grey Melange Melange Melange Melange Melange Melange Melange Melange Step STANDARD 100 by OEKO-TEX® EU Ecolabel 100% Trevira CS Beige Dark Grey Grey Grey Blue Light Blue Light Grey 4 100.000 8 4 – 5 CAL TB 117 Polyester Melange Green Crib 5 61004 60090 60011 66152 67004 60004 BS 5852 Source 0 + 1 FABRIC ST203 ST202 ST208