Constitutional Conference (1994-95)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate Committee Report

THE 7TH SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION REPORT OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON THE REVIEW OF THE 1999 CONSTITUTION ON A BILL FOR AN ACT TO FURTHER ALTER THE PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 1999 AND FOR OTHER MATTERS CONNECTED THEREWITH, 2013 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria referred the following Constitution alterations bills to the Committee for further legislative action after the debate on their general principles and second reading passage: 1. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.107), Second Reading – Wednesday 14th March, 2012 2. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.136), Second Reading – Thursday, 14th October, 2012 3. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.139), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 4. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.158), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 5. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.162), Second Reading – Thursday, 4th October, 2012 6. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.168), Second Reading – Thursday 1 | P a g e 4th October, 2012 7. Constitution (Alteration Bill) 2012 (SB.226), Second Reading – 20th February, 2013 8. Ministerial (Nominees Bill), 2013 (SB.108), Second Reading – Wednesday, 13th March, 2013 1.1 MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE 1. Sen. Ike Ekweremadu - Chairman 2. Sen. Victor Ndoma-Egba - Member 3. Sen. Bello Hayatu Gwarzo - “ 4. Sen. Uche Chukwumerije - “ 5. Sen. Abdul Ahmed Ningi - “ 6. Sen. Solomon Ganiyu - “ 7. Sen. George Akume - “ 8. Sen. Abu Ibrahim - “ 9. Sen. Ahmed Rufa’i Sani - “ 10. Sen. Ayoola H. Agboola - “ 11. Sen. Umaru Dahiru - “ 12. Sen. James E. -

Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Assembly Complex, Three-Anns Zone, Abuja

5TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THIRD SESSION No. 33 467 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 10th October, 2006 1. The Senate met at 10:30 a.m. The Senate President read Prayers. 2. Votes and Proceedings: The Senate President announced that he had examined the Votes and Proceedings of Thursday, 5th October, 2006 and approved same. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings were adopted. 3. Message from Mr. President: The Senate President announced that he had received a letter from Mr. President, Commander-in-Chief which he read as follows: PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OP NIGERIA PRES/134 _ 6 October, 2006 Senator Ken Nnamani, President of the Senate, Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Assembly Complex, Three-Anns Zone, Abuja Dear President of the Senate, 2007 Budget * / do crave the indulgence of the National Assembly to grant me the slot of Wednesday, October 11, 2006, at 12:00 noon to formally address the Joint Session of the National Assembly on Budget 2007. While I thank you for your cooperation and understanding, please accept, Mr Senate President, the assurances of my highest consideration. Yours Sincerely, Signed: OLUSEGUN OBASANJO PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 468 _____________________________ Tuesday, 10th October, 2006 ___________________________No. 33 4. Closed Session: Morion made and Question Proposed: That the Senate do resolve into a Closed Session to deliberate on matters relevant to the workings of the Senate (Senate Majority Leader). Question put and agreed to. Senate in Closed Session — 10: 45 a .m. Senate in Open Session — 11.25 a.m The Senate President reported that the Senate in Closed Session deliberated on the fumigation of Apo Legislative Quarters in view of the prevalence of reptiles within the premises. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 30Th November, 2010

6TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOURTH SESSION No. 45 621 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 30th November, 2010 1. The Senate met at 10:56 a.m. The Senate President read prayers. 2. Votesand Proceedings: The Senate President announced that he had examined the Votes and Proceedings of Thursday, 25th November, 2010 and approved same. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings were approved. 3. Messagefrom Mr. President: The Senate President announced that he had received a letter from the President, Commander-in- Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federation, which he read as follows: Appointment of a new Chairman for the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC): PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 25th November, 2010 Senator David Mark, GCON President of the Senate, Senate Chambers, National Assembly, Three Arms Zone, Abuja. Your Excellency, APPOINTMENT OF A NEW CHAIRMAN FOR THE INDEPENDENT CORRUPT PRACTICES AND OTHER RELATED OFFENCES COMMISSION PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 622 Tuesday, 30th November, 2010 No. 45 In line with the provision of Section 3 of the Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Act, Cap C.3l, LFN 2004, I forward the name of Bon. Justice Pius Olayiwola Aderemi, JSC, CON along with his curriculum vitae for kind consideration and confirmation by the Senate for appointment as Chairman of the Independent Corrupt Practices and other Related Offences Commission. Distinguished President of the Senate, it is my hope that, in the usual tradition of the Senate of the Federal Republic, this will receive expeditious consideration. Please accept, as usual, the assurances of my highest consideration. -

FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15Th May, 2013 1

7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION NO. 174 311 THE SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 1. Prayers 2. Approvalof the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. National Agricultural Development Fund (Est. etc) Bill 2013(SB.299)- First Reading Sen. Abdullahi Adamu (Nasarauia North) 2. Economic and Financial Crime Commission Cap E 1 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB. 300) - First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Be1l11eNorth East) 3. National Institute for Sports Act Cap N52 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB.301)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 4. National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) Act Cap N30 LFN 2011 (Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.302)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade tBenue North East) 5. Federal Highways Act Cap F 13 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013(SB. 303)- First Reading Sen. Banabas Gemade (Benue North East) 6. Energy Commission Act Cap E 10 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bill 2013 (SB.304)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross Riner North) 7. Integrated Farm Settlement and Agro-Input Centres (Est. etc) Bill 2013 (SB.305)- First Reading Sen. Ben Ayade (Cross River North) PRESENTATION OF A REPORT 1. Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions: Petition from Inspector Emmanuel Eldiare: Sen. Ayo Akinyelure tOndo Central) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Committee on Ethics, Privileges and Public Petitions in respect of a Petition from INSPECTOR EMMANUEL ELDIARE, on His Wrongful Dismissal by the Nigeria Police Force" - (To be laid). PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 312 Wednesday, 15th May, 2013 174 ORDERS OF THE DAY MOTION 1. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22Nd December, 2010

6TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOURTH SESSION No. 54 703 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22nd December, 2010 1. The Senate met at 11.04 a.m. The Senate President read prayers. 2. Votes and Proceedings: The Senate President announced that he had examined the Votes and Proceedings of Tuesday, 21st December, 2010 and approved same. By unanimous consent, the Votes and Proceedings were approved. 3. Announcement: Re-constitution of Committees: The Senate President announced the re-constitution of some Committees as follows: (z) Chairman, Committee on Works Senator Anyim Ude (il) Chairman, Committee on Education Senator Uche Chukwumerije (iil) Chairman, Committeeon Aviation Senator Sylvester N. Anyanwu (iv) Chairman, Committee on Science & Technology Senator Chris N. D. Anyanwu (v) Chairman, Committee on Special Duties Senator Gregory Ngaji (vz) Chairman, Committee on Police Affairs Senator Lekan Mustapha (vb) Chairman, Committee on Internal Affairs Senator Gbenga Ogunniya .(viii) Chairman, Committee on Cooperation and Integration in Africa and NEPAD Senator Joseph 1. Akaagerger (ix) Vice Chairman, Committee on Local & Foreign Debts Senator George Akume Committee on Communications: (z) Senator Patrick E. Osakwe Chairman (b) Senator Kabiru 1. Gaya Vice Chairman (iiz) Senator Odion Ugbesia Member (iv) Senator Abubakar A. Bagudu Member (v) Senator Nuhu Aliyu Member (vi) Senator Yisa Braimoh Member (viz) Senator Suleiman M. Nazif Member (viil) Senator Patricia N. Akwashiki Member (ix) Senator Abubakar U. Gada Member (x) Senator Abdulaziz Usman Member (Xl) Senator Umar A. Argungu Member (xiI) Senator Abubakar Tanko Ayuba Member (xiiz) Senator Ayogu Eze Member PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 704 Wednesday, 22nd December, 2010 No. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 13Th February, 2013

7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION No. 54 537 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 13th February, 2013 1. The Senate met at 10:45 a.m. The Senate President read prayers. 2. Votes and Proceedings: The Senate examined the Votes and Proceedings of Tuesday, 12th February, 2013. Question was put and the Votes and Proceedings were approved by unanimous consent. 3. Announcements: (a) ~eetUng: The Senate President read a letter from Senator Hope Uzodimma (Imo West) as follows: SOUTHERN SENATORS FORUM NATIONAL ASSE~BLY .~BUJA 13th. February, 2013 His Excellency, Sen. David Mark GCON, fnim, President of the Senate, Federal Republic of Nigeria, National Assembly, Abuja. SOUTHERN SENATORS MEETING May I crave the indulgence of your Excellency to make the following announcements viz: Southern Senators Forum Meeting Date: February ir, 2013 Venue: Hearing Room 1, National Assembly Complex Time: 30 minutes after Plenary Note: Attendance Mandatory Do please accept the assurances of my highest esteem. (Signed) Senator Hope Uzodimma (Secretary) PRINTED BY NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 538 VVednesday, 13th February, 2013 No. 54 (b) Acknowledgment: The Senate President acknowledged the presence of the following who were in the gallery to observe Senate Proceedings: (z) Staff and Students of Pacesetters Academy, Wuye, Abuja; and (it) Members of the Students' Representative Council, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State. 4. Petition: Rising on Rule 41, Senator Victor Lar (Plateau South) drew the attention of the Senate to a petition from his constituents, Mr. Gideon Pam and Others on the lingering impasse with the MTN Call Centers in Jos. -

Global Journal of Human Social Science

Online ISSN : 2249-460X Print ISSN : 0975-587X DOI : 10.17406/GJHSS The Politics of Labeling An Appraisal of Voters National Election of Ethiopia Implications on Nigeria Democracy VOLUME 17 ISSUE 1 VERSION 1.0 Global Journal of Human-Social Science: F Political Science Global Journal of Human-Social Science: F Political Science Volume 17 Issue 1 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. *OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Social Sciences. 2017. Open Scientific Standards $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 7KLVLVDVSHFLDOLVVXHSXEOLVKHGLQYHUVLRQ Publisher’s Headquarters office RI³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO ® 6FLHQFHV´%\*OREDO-RXUQDOV,QF Global Journals Headquarters $OODUWLFOHVDUHRSHQDFFHVVDUWLFOHVGLVWULEXWHG 945th Concord Streets, XQGHU³*OREDO-RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, 6FLHQFHV´ 5HDGLQJ/LFHQVHZKLFKSHUPLWVUHVWULFWHGXVH United States of America (QWLUHFRQWHQWVDUHFRS\ULJKWE\RI³*OREDO USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 -RXUQDORI+XPDQ6RFLDO6FLHQFHV´XQOHVV USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 RWKHUZLVHQRWHGRQVSHFLILFDUWLFOHV 1RSDUWRIWKLVSXEOLFDWLRQPD\EHUHSURGXFHG Offset Typesetting RUWUDQVPLWWHGLQDQ\IRUPRUE\DQ\PHDQV HOHFWURQLFRUPHFKDQLFDOLQFOXGLQJ G lobal Journals Incorporated SKRWRFRS\UHFRUGLQJRUDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQ 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, VWRUDJHDQGUHWULHYDOV\VWHPZLWKRXWZULWWHQ SHUPLVVLRQ Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom 7KHRSLQLRQVDQGVWDWHPHQWVPDGHLQWKLV ERRNDUHWKRVHRIWKHDXWKRUVFRQFHUQHG -

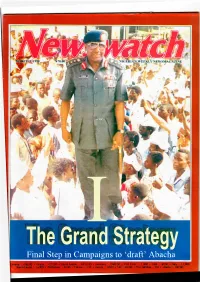

Abacha C Newswatch OVERSEAS SUBSCRIPTION)

* '€■ 'sa*. %. i-M’ I The Grand Strategy Final Step in Campaigns to ‘draft’ Abacha C Newswatch OVERSEAS SUBSCRIPTION) This is to inform our numerous overseas readers and subscribers that we have resumed our Internationa} subscriber service. INTERNATIONAL SUBSCRIPTION RATES Newswatch ■U.KPBICES WWW 2 o co O) in Overseas Special Offer! 1 year (52 issues) Students 6 months 4(26 issues) Students cm One Month Free 3 months (13 issues) Students Subscription For The First 200 New Subscribers EUROPE/EIRE PRICES ^ -vi 1 Year (52 issues) £100 - Students cd BEAT THE RUSH !! 6 Months (26 issues) £55 - Students I s> to to to to to to 3 Months (13 issues) £30 - Students ro 4^ en o O USA/CANADA/ SOUTH AMERICA PRICES <N o o o 1 Year (52 issues) Students O T- 'si 6 Months (26 issues) Students cn AUSTRALIA/ FAR EAST PRICES 1 Year (52 issues) o students o> cn o to to cn 6 Months (26 issues) to to O 4^ students NORTH AFRICA/ MIPPLE EAST,PRICES 8 04 1 Year (52 issues) LO cn students o O to to 6 Months (26 issues) <j> students AFRICA (OTHER THAN ABOVE) 1 Year (52 issues) £130 students cd to to cn 6 Months (26 issues) £65 students cn Name:. Address:.................... .............. ................................... ...................................... ............................................ Tick l I Installments! Payment or I............... I Full Payment Enclosed here is a bank draft/cheque for.................................. ............................ ......................................... Signature:........ ...................................... .......................... ............................................................................. : NOTE: All students subscription must be accompanied by CURRENT EVIDENCE OF SCHOOL REGISTRATION. Cheques, Sterling Postal Order/Steriing Money Order should be made payable to NIGERIAN MAGAZINES LIMITED Existing and new Subscribers and Advertisers should contact:- Nigerian Magazines Limited. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 5Th June, 2007

6TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION No. 1 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 5th June, 2007 1. The Senate met at 10: 20 a.m. pursuant to the proclamation by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Umaru Musa Yar'Adua. PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA PROCLAMATION FOR THE HOLDING OF THE FIRST SESSION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WHEREAS it is provided in Section 64(3) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999, that the person elected as President shall have power to issue a proclamation for the holding of the First Session of the National Assembly immediately after his being sworn in. Now THEREFORE, 1, Umaru Musa Yar'Adua, President and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, in exercise of the powers bestowed upon me by Section 64(3) aforesaid, and of all other powers enabling me in that behalf hereby proclaim that the First Session of the National Assembly shall hold at 10:00 a.m. on Tuesday, 5th June, 2007 in the National Assembly, Abuja. Given under my hand and the public seal of the Federal Republic of Nigeria at Abuja, this day 30h of May, 2007. Signed: UMARU MUSA YAR'ADUA 2. At 10.20 a.m. the Clerk to the National Assembly called the Senate to order and informed Senators-Elect that writs had been received in respect of the election held on 14th April, 2007 in accordance with the Constitution. He then proceeded with the roll call of Senators-elect State by State: ABIA STATE S/No Name of Senator-Elect Senatorial District 1 Nkechi J. -

Nigerian Writers

Society of Young Nigerian Writers Chris Abani From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Chris Abani The poem "Ode to Joy" on a wall in the Dutch city of Leiden Christopher Abani (or Chris Abani) (born 27 December 1966) is a Nigerian author. He is part of a new generation of Nigerian writers working to convey to an English-speaking audience the experience of those born and raised in "sthat troubled African nation". Contents 1 Biography 2 Education and career 3 Published works 4 Honors and awards 5 References 6 External links Biography Chris Abani was born in Afikpo, Nigeria. His father was Igbo, while his mother was English- born.[1] He published his first novel, Masters of the Board (1985) at the age of sixteen. The plot was a political thriller and it was an allegory for a coup that was carried out in Nigeria just before it was written. He was imprisoned for 6 months on suspicion of an attempt to overthrow the government. He continued to write after his release from jail, but was imprisoned for one year after the publication of his novel, Sirocco. (1987). After he was released from jail this time, he composed several anti-government plays that were performed on the street near government offices for two years. He was imprisoned a third time and was placed on death row. Luckily, his friends had bribed government officials for his release in 1991, and immediately Abani moved to the United Kingdom, living there until 1999. He then moved to the United States, where he now lives.[2] Material parts of his biography as it relates to his alleged political activism, imprisonments and death sentence in Nigeria have been disputed as fiction by some Nigerian literary activists of the period in question. -

THE SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 19Th November, 2013 1

7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY - THIRD SESSION NO. 67 124 THE SENATE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 19th November, 2013 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999(Alteration) Bi112013(SB.393)- First Reading Sen. Ademola A. Adeseun (Oyo Central) ..../ 2. Standards Organisation Act CAP S.9 LFN 2011(Amendment) Bi112013(SB.394)- First Reading Sen. Nenadi E.Usman (Kaduna South) ~ PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 1. Report of the Joint Committee on Sports and Social Development and National Planning, Economic Affairs and Poverty Alleviation: National Social Welfare Commission Bill 2013 (SB.115) Sen. Adamu I. Gumba (Bauchi South) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Joint Committee on Sports and Social Development and National Planning, Economic Affairs and Poverty Alleviation, on the National Social Welfare Commission Bill 2013(S8.115)- To be laid. 2. Report of the Joint Committee on Sports and Social Development and Women Affairs and Youth Development: Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Bill 2013 (SB.I02) Sen. Adamu I. Gumba (Bauchi South) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Joint Committee on Sports and Social Development and Women Affairs and Youth Development, on the Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Bill 2013(SB.102)- (To be laid) 3. Report of the Committee on Cooperation, Integration in Africa and NEPAD New Partnership for Africa's Development Commission (Est. etc) Bill 2013 (SB. 121) Sen. Simeon S. Ajibola (Kuiara South) "That the Senate do receive the Report of the Committee on Cooperation, Integration in Africa and NEPAD, on the New Partnership for Africa's Development Commission (Est.