Trends 1990-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exonyms – Standards Or from the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4

NO. 50 JUNE 2016 In this issue Preface Message from the Chairperson 3 Exonyms – standards or From the Secretariat Message from the Secretariat 4 Special Feature – Exonyms – standards standardization? or standardization? What are the benefits of discerning 5-6 between endonym and exonym and what does this divide mean Use of Exonyms in National 6-7 Exonyms/Endonyms Standardization of Geographical Names in Ukraine Dealing with Exonyms in Croatia 8-9 History of Exonyms in Madagascar 9-11 Are there endonyms, exonyms or both? 12-15 The need for standardization Exonyms, Standards and 15-18 Standardization: New Directions Practice of Exonyms use in Egypt 19-24 Dealing with Exonyms in Slovenia 25-29 Exonyms Used for Country Names in the 29 Repubic of Korea Botswana – Exonyms – standards or 30 standardization? From the Divisions East Central and South-East Europe 32 Division Portuguese-speaking Division 33 From the Working Groups WG on Exonyms 31 WG on Evaluation and Implementation 34 From the Countries Burkina Faso 34-37 Brazil 38 Canada 38-42 Republic of Korea 42 Indonesia 43 Islamic Republic of Iran 44 Saudi Arabia 45-46 Sri Lanka 46-48 State of Palestine 48-50 Training and Eucation International Consortium of Universities 51 for Training in Geographical Names established Upcoming Meetings 52 UNGEGN Information Bulletin No. 50 June 2106 Page 1 UNGEGN Information Bulletin The Information Bulletin of the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (formerly UNGEGN Newsletter) is issued twice a year by the Secretariat of the Group of Experts. The Secretariat is served by the Statistics Division (UNSD), Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Secretariat of the United Nations. -

Egovernment in Slovenia

Country Profile Recent Developments Strategy Legal Framework Actors Who’s Who Infrastructure Services for Citizens Services for Businesses INSIDE WHAT’S eGovernment in Slovenia ISA2 Visit the e-Government factsheets online on Joinup.eu Joinup is a collaborative platform set up by the European Commission as part of the ISA² programme. ISA² supports the modernisation of the Public Administrations in Europe. Joinup is freely accessible. It provides an observatory on interoperability and e-Government and associated domains like semantic, open source and much more. Moreover, the platform facilitates discussions between public administrations and experts. It also works as a catalogue, where users can easily find and download already developed solutions. The main services are: • Have all information you need at your finger tips; • Share information and learn; • Find, choose and re-use; • Enter in discussion. This document is meant to present an overview of the eGoverment status in this country and not to be exhaustive in its references and analysis. Even though every possible care has been taken by the authors to refer to and use valid data from authentic sources, the European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the included information, nor does it accept any responsibility for any use thereof. Cover picture © Fotolia Content © European Commission © European Union, 2017 Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. eGovernment in Slovenia March 2017 Edition 3.00 Country Profile ..................................................................................................... -

The Julian Alps Slightly Smaller Than the U.S

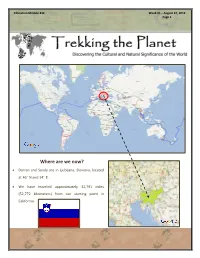

Education Module #32 Week 31 – August 27, 2012 Page 1 Where are we now? Darren and Sandy are in Ljubljana, Slovenia, located at 46 N and 14 E. We have traveled approximately 32,791 miles (52,772 kilometers) from our starting point in California. Education Module #32 Week 31 – August 27, 2012 Page 2 People and Culture Slovenia was part of the Roman Empire in the first century B.C. and an element of the Holy Roman Empire. It belonged to the Habsburg Empire from the 14th century until the end of World War I in 1918. The Kingdom of the Serbs was formed with Slovenia, Montenegro, Serbia and Croatia in 1918. This name was changed to Yugoslavia in 1929. After World War II Slovenia was communist Yugoslavia’s most prosperous Lujubljana’s Dragon Bridge (source: Flickr.com/Alistair Young) republic. It declared its independence in 1991. About 10% of the country’s two million population lives in the capital city of Ljubljana. A famous landmark Did you know? is the “Zmajski Most” or Dragon Bridge. Legend says Lace -making in the town of Idrija is a Slovenian tradition. that the founder of Ljubljana killed a dragon, Products made from lace include napkins, curtains, bed symbolized by one of the four statues on the bridge. linens and clothes. The origins date back to the 17th The official language is Slovene. Slovenia’s historical century. Idrija opened a lace ties to Western Europe mean that Italian and school in 1876 and holds a lace festival each year. Hungarian are also widely spoken. -

Digital Government Factsheet Slovenia

Digital Government Factsheet 2019 Slovenia ISA2 Digital Government Factsheets - Slovenia Table of Contents Country Profile .................................................................................................. 3 Digital Government Highlights ............................................................................. 6 Digital Government Political Communications ........................................................ 7 Digital Government Legislation ...........................................................................13 Digital Government Governance .........................................................................18 Digital Government Infrastructure ......................................................................24 Digital Government Services for Citizens .............................................................35 Digital Government Services for Businesses .........................................................45 2 2 Digital Government Factsheets - Slovenia Country Profile Basic data Population: 2 066 880 inhabitants (2018) GDP at market prices: 45 947 million Euros (2018) GDP per inhabitant in PPS (Purchasing Power Standard EU 28=100): 85% (2017) GDP growth rate: 4.5% (2018) Inflation rate: 1.9% (2018) Unemployment rate: 5.4% (2018) General government gross debt (Percentage of GDP): 70.1% (2018) General government deficit/surplus (Percentage of GDP): 0.7% (2018) Area: 20 273 km² 2 Capital city: Ljubljana Official EU language: Slovenian Currency: Euro Source: Eurostat (last update: 15 March 2019) -

Slovenian Symbols Songs of Freedom 02/03

SLOVENIAN SYMBOLS SONGS OF FREEDOM 02/03 HAVE YOU HEARD? The basis for the coat of arms :: NATIONAL SYMBOLS THROUGH TIME of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia was the Slovenian :: :: BACK TO THE FUTURE Liberation Front emblem, designed during the Second World War by the architect Edvard Ravnikar. As a country in the heart of the old continent, Slovenia has a rich story to tell and great symbols attached to its chest. It has been a proud part of several multinational empires, kingdoms, and countries that all influenced the national insignia of to- day’s Republic of Slovenia. CARANTANIA THE PRINCE’S COAT OF ARMS COAT OF ARMS ROYAL COAT OF ARMS OF THE COAT OF ARMS OF THE SOCIALIST COAT OF ARMS STONE OF THE COUNTS OF CELJE OF CARNIOLA KINGDOM OF YUGOSLAVIA REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA Carantania, one of the first Slavic This ancient symbol of The medieval aristocratic Under the Habsburg Initially known as the Kingdom Slovenia was one of six republics states, covered the territories Slovenian identity can also be family of the Counts of Celje monarchy, the Duchy of of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, within the Federal Republic of present-day Slovenia and found on the two-cent euro was the last native noble house Carniola was the main the Kingdom of Yugoslavia of Yugoslavia for much of the Austria in the second half of the coin. The Prince’s Stone was to rule the Slovenian lands. Slovenian-populated crown extended from the western twentieth century, from 1943 seventh century. Although the used as a ceremonial throne The three golden six-pointed land, with its capital in Balkans to Central Europe until independence in 1991. -

Egovernment in Slovenia

Country Profile History Strategy Legal Framework Actors Who’s Who Infrastructure Services for Citizens Services for Businesses INSIDE WHAT’S eGovernment in Slovenia ISA Visit the e-Government factsheets online on Joinup.eu Joinup is a collaborative platform created by the European Commission under the ISA programme. ISA supports the modernization of Public administrations in Europe through the development of interoperable services, frameworks and tools. Joinup provides numerous services around 3 main functionalities: 1. An observatory on interoperability, e-government, e-inclusion and e-health 2. A collaborative platform of open communities 3. A repository of interoperability solutions This document is meant to present an overview of the eGoverment status in this country and not to be exhaustive in its references and analysis. Even though every possible care has been taken by the authors to refer to and use valid data from authentic sources, the European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the included information, nor does it accept any responsibility for any use thereof. Cover picture © Fotolia Content © European Commission © European Union, 2015 Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. eGovernment in Slovenia, February 2016, Edition 19.0 Country Profile ...................................................................................................... 1 eGovernment History ............................................................................................ 7 eGovernment Strategy ....................................................................................... -

On the Origin of Alpine Slovenes

On the Origin of Alpine Slovenes Aleš Iglič University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia Some historians believe that Slovenes were drawn into the European cultural circle by (Bavarian) feudalism, although it is this very same feudalism that also prevented them access to the resources needed for their social and cultural development – it is precisely this fact, they suggest, that presented one of the most significant obstacles for the further development of the Slovene nation. We cannot agree with this viewpoint. Rather, Slovenes owe their inclusion in the medieval European civilisation, which originates from European antique traditions stemming from ancient Greece, primarily to Roman and other indigenous peoples, as well as to Christian missionaries from the non-Germanic parts of Europe (Iglič, 2007a), i.e. Ireland and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, who spread Christianity and the culture of the antiquity in the region of the Diocese of Salzburg, from where missionaries came to Carantania, Carniola and Lower Pannonia (Fig. 1). The first Apostle of Carantania Modestus, for example, was sent to Carantania on the orders of the Irish monk Vergilius of Salzburg (Gruden, 1992). Overall, Irish monks contributed greatly to the preservation of the European civilisation in the Early Middle Ages also in other parts of Europe (Cahill, 1995). By passing on the preserved antique knowledge, for example literacy, onto the barbarian peoples, Byzantine missionaries from Greece and Aquileia (Grivec, 1927; Bratož, 1990) as well as Irish missionaries (monks) preserved the European civilisation, which is based on the accomplishments of ancient Greece in the fields of philosophy, science, art, and political organisation (democracy). -

Slovenia As an Outpost of Th~ Third Reich

SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF TH~ THIRD REICH By HELGA HORIAK HARRIMAN 1\ Bachelor of Arts Wells College Aurora, New York 1952 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1969 STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 29 1969 SLOVENIA AS AN OUTPOST OF THE THIRD REICH Thesis Approved: Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE This study is concerned primarily with the Nazi occupation of Northern Yugoslavia during 1941 and 1942. Hitler's plan for converting Slovenia into a germanized frontier zone of the Third Reich is assessed in the light of Slovene history, most particularly since 1918. The evidence for the Nazi resettlement program designed to achieve Hitler's goal came from manuscript documents, which were written largely by the SS officers in charge of population manipulation. I wish to express appreciation to members of my advisory committee t from the Department of History at Oklahoma State University who gave helpful criticism in the preparation of the text. Professor Douglas Hale served as committee chairman and offered valuable advice concern- ing the study from its inception to its conclusion. Professor George Jewsbury imparted to its development his own keen understanding of Eastern Europe. To Professors John Sylvester and Charles Dollar, who read the study in its final form, I am also indebted. In addition, I wish to thank my father, Dr. E. A. V. Horiak, for his insightful comments. Dr. Joseph Suhadolc of the Department of For- eign Languages at Northern Illinois University gave freely of his time in reviewing the text. -

The Slovene Language in Education in Italy

The Slovene language in education in Italy European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by SLOVENE The Slovene language in education in Italy | 3rd Edition | c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province of Fryslân. © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning, 2020 ISSN: 1570 – 1239 3rd edition The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. This Regional dossier was edited by Norina Bogatec, SLORI - Slovenski raziskovalni inštitut (Slovene research institute). Maria Bidovec, Norina Bogatec, Matejka Grgič, Miran Košuta, Maja Mezgec, Tomaž Simčič and Pavel Slamič updated the previous dossier in 2004. Unless otherwise stated academic data refer to the 2017/2018 school year. Contact information of the authors of Regional dossiers can be found in the Mercator Database of Experts (www.mercator-research.eu). Anna Fardau Schukking has been responsible for the publication of this Mercator Regional dossier. Contents Contents Glossary 2 Foreword 3 Glossary -

Word Prosody in Slovene from a Typological Perspective

Sprachtypol. Univ. Forsch. (STUF), Berlin 56 (2003) 3,234-251 MARCL. GREENBERG(Lawrence) Word prosody in Slovene from a typological perspective Abstract Slovene is, along with Serbo-Croatian, an example of a pitch-accent language, one of the only two remaining among the Slavic family. In most of the literature on Slovene, the data on the word-prosody features of this language are taken from the standardized system, a somewhat constructed entity based on the pitch-accent systems of selected dialects. The present survey attempts to give a coherent structural description of the word-prosodic phenomena as they are manifested in the extraordinarily variegated Slovene dialects; these in turn are compared to the standardized system as well as, where relevant, to typologically similar systems found in Croatian dialects. In addition, the key innovations that shaped the prosodic systems of Slovene dialects are discussed. Slovene emerges as a special set of types that share a tendency to concentrate prosodic distinctions - pitch and quantity - in the one stressed syllable of each accented word. Furthermore, these pitch and quantity distinctions in many dialects have become rephonologized as vowel-quality distinctions. A few aberrant local dialects have gained new pitch distinctions or unstressed quantity distinctions. Prozodija slovenske besede tipoloiko SlovenSEina je kot srbohrvaSEina tonemski jezik, eded izmed samo dveh, ki sta Se taka v slovanski jezikovni drusini. PreteZni del strokovne literature o slovenSEini jemlje podatke o besedni prozodiji tega jezika iz knjifnega sistema, ki je v dololieni meri narejen na podlagi tonemskih sistemov izbranih naref ij. V tem pregledu skuSam podati sovisen strukturni opis prozoditnih pojavov na besedni ravnini, kot obstajajo v izjemno pestrih slovenskih naretjih; slednja se prime jajo tudi s knjiZnim sistemom in, kjer so razlogi, s tipoloSko podobnimi sistemi v hrvaSkih naretjih. -

Slovene: Official Language of Slovenia

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Country Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Country: Slovene Author: Lisa Salisbury Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) + Slovene Popa, 2011 Popa, 2011 Official Language of Slovenia By Lisa Salisbury February 2012 + Slovenia A country in Central Europe touching the Alps and bordering the Mediterranean, Italy, Croatia, Hungary, Austria, and the Adriatic Sea. Slovene Language Native language of about 88% of Slovenia’s population 5 dialect bases incorporating 50 varying dialects Also spoken in parts of Italy, Austria, Hungary, and Croatia Wikipedia, 2012 Ager, 2012 + Dialects Slovene is an Indo-European language from South Slavic branch of the Slavic languages, like Serbian and Croatian. The spoken and written language is uniform and standardized. Dialects’ differ considerably in phonology, vocabulary and grammar Dialect Regions in Slovenia Dnik, 2009 46 clearly defined dialects, divided into six regional groups: Carinthian, Upper Carniolan, Lower Carniolan, Littoral, Rovte, Styrian and Pannonian Ager, 2012; Dular, 2001 + Characteristics of Slovene Dual grammatical number 2 accentual norms: Pitch accent, Abundant inflection Tense-Verb distinction Flexible word order-adjusted for emphasis/stylistic reasons Stress can fall on any syllable of a word Pronounce every letter in words Second-person plural forms used for individuals as sign of respect Word endings express -

CARNIOLA, PATRIA SCLAVORUM Carniola Occupied a Central

CHAPTER EIGHT CARNIOLA, PATRIA SCLAVORUM Carniola occupied a central place among the Länder settled by a Slovene-speaking population that were part of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy from the Middle Ages until its disintegration in 1918; at least that is how the Slovenes conceived Carniola from their national rise onwards. Its central place within the Slovene-settled area was refl ected by both its geographical location and ethnical/linguistic structure. Accordingly, the Slovene language was also referred to as the “Carniolan language,” the Land’s capital Ljubljana gained the importance of the national centre of the Slovenes, and the white-blue-red Carniolan fl ag was adopted as the Slovene national fl ag in 1848. Triglav, the highest mountain of Carniola, became one of the principal Slovene national symbols and, fi nally, Carniola was the only historical Land inhabited by Slovenes that was annexed in its entirety to the new Yugoslav com- munity aft er 1918; the integration into the new state however also meant the abolition of its constitutional order as a Land whose roots extended back to the Middle Ages. It is therefore all the more interest- ing that the beginnings of the period in the history of Carniola, where, based on a suffi cient number of historical sources, its development can be traced consistently and continuously, is marked by two charters of Emperor Otto II that date from as late as 973: the fi rst mentions Carniola /…/ quod vulgo Creina marcha appellatur, and the second in regione vulgari vocabulo Chreine.1 We should add, though, that the number of written sources on the entire Early Middle Ages, from the settlement of the Slavs in the Eastern Alps and pre-Alpine area to the end of the Carolingian age, is so scarce for this particular region that we can count them on the fi ngers of one hand.