Population Awareness of Cardiovascular Disease and Its Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon

Aging Medicine and Healthcare 2020;11(1):10-19. doi:10.33879/AMH.2020.033-1904.010 Aging Medicine and Healthcare https://www.agingmedhealthc.com Original Article Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon *Agbor Nathan Emeh1,2, Fongang Che Landis1,3, Tambetakaw Njang Gilbert1,2, Atongno Ashu Humphrey1,2 1University of Buea, Cameroon 2Ministry of Public Health, Yaounde, Cameroon 3Cameroon Christian University, Cameroon ABSTRACT Background/Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the socio- clinical profile, heath status and determine the impact of age on health related behaviors of geriatric population in the Buea Health District. Since studies on the subject are lacking in Cameroon, we believe this study provides ground work for further studies on geriatrics in Cameroon. Methods: Two-stage systematic sampling was used. Firstly, 30 communities of the Buea Health District were randomly selected. Eligible participants in these communities were then selected in turns. Interviewer-administered questionnaire, physical examination and health record checks were used to capture the study objectives. Results: Of the 142 sampled elderlies, 57.7% (82/142) were females with the young-old (60-75 years) constituted the majority (69.01%; 98/142). Most of the elderlies (88%; 125/142) had at least one chronic disease, 35.9% (51/142) had *Correspondence at least two and 9.86% (14/142) had at least three chronic diseases. The major Dr. Agbor Nathan Emeh chronic diseases suffered by elderlies included arthritis (38.73%; 55/142), gastritis (38.73%; 55/142) and hypertension (29.58%; 42/142). Most affected Department of Public Health body systems were musculoskeletal (86.62%; 123/142), neurologic (85.21%; and Hygiene, University of 121/142), and eye (76.76%; 109/142). -

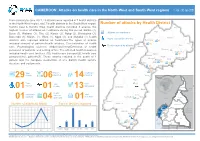

SSA Infographic

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

Ownership, Coverage, Utilisation and Maintenance of Long

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/465005; this version posted February 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Ownership, Coverage, Utilisation and Maintenance of Long-lasting insecticidal nets in Three Health Districts in Cameroon: A Cross- Sectional Study Frederick Nchang Cho1,2,3, Paulette Ngum Fru4,5, Blessing Menyi Cho6, Solange Fri Munguh6, Patrick Kofon Jokwi6,7, Yayah Emerencia Ngah8, Celestina Neh Fru9,10, Andrew N Tassang10,11,12, Peter Nde Fon4,13, Albert Same Ekobo14,15 1Global Health Systems Solutions, Cameroon. 2Infectious Disease Laboratory, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 3Central African Network for Tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and Malaria (CANTAM), University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 4Department of Public Health and Hygiene, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 5District Health Service Tiko, South West Regional Delegation of Health, Ministry of Health, Cameroon. 6Catholic School of Health Sciences, Saint Elizabeth Hospital Complex, P.O. Box 8 Shisong-Nso, Cameroon. 7Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board (CBCHB) – HIV Free Project, Kumbo-Cameroon. 8District Hospital Bali, Ministry of Public Health, Cameroon. 9Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 10Atlantic Medical Foundation, Mutengene-Cameroon. 11Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Buea, Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 12Buea Regional Hospital Annex, Cameroon. 13Solidarity Hospital, Buea-Cameroon. 14Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Douala, Cameroon. 15Parasitology Laboratory, University Hospital Centre of Yaoundé, Cameroon. -

Wabane Communal Development Plan

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON ------------ --------- Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland ----------- ---------- MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DE LA MINISTRY OF ECONOMY, PLANNING AND PLANIFICATION ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT TERRITOIRE ---------- ------------- GENERAL SECRETARY SECRETARIAT GENERAL ---------- ------------ NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME NATIONAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT PROGRAM PARTICIPATIF ---------- ------------ SOUTH WEST REGIONAL COORDINATION UNIT CELLULE REGIONALE DE COORDINATION DU ------------ SUD OUEST ------------ Wabane Communal Development Plan Wabane Council February 2012 WABANE COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………………………………………….…i i. List of tables.................................................................................................................ii ii. List of photos...............................................................................................................iii iii. List of maps...................................................................................................................iv iv. List of annexes................................................................................................................v v. List of abbreviations......................................................................................................vi vi. Executive summary.......................................................................................................ix 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................1 -

Urbanization and the Politics of Identity in Buea: a Sociological Perspective Fanny Jose Mbua B.Sc

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) Volume 4 Issue 5, July-August 2020 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470 Urbanization and the Politics of Identity in Buea: A Sociological Perspective Fanny Jose Mbua B.Sc. MSc, PhD (In view) University of Buea, South West Region, Cameroon, Central Africa ABSTRACT How to cite this paper: Fanny Jose Mbua Urbanization plays a distinct and important role in producing political "Urbanization and the Politics of Identity relationships. Identity politics which is strongly linked to sense of belonging is in Buea: A Sociological Perspective" an important dimension of political relationships in urban areas. This study Published in examines the relationship between urbanization and the politics of identity in International Journal Buea. The research is a descriptive documentary research with data collected of Trend in Scientific from secondary sources (former studies and reports, newspapers, archival Research and records and internet publications) with few interviews. Data collection Development (ijtsrd), procedures included reading and note-taking. Data was analyzed using ISSN: 2456-6470, thematic content analysis whereby concepts and ideas were grouped together Volume-4 | Issue-5, IJTSRD33078 under umbrella key words to appreciate the trends in them. The August 2020, pp.772- Instrumentalist Theory of Ethnicity was the framework that guided the study. 798, URL: The themes were geared towards outlining how ethnicity has been a tool of www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd33078.pdf political control. Data was gathered from the different epochs that have marked urbanization in Buea, from the Native Authority to the present Buea Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Rural Council, demonstrating how this has influenced relationships between International Journal of Trend in Scientific natives and non-natives. -

In Southwest and Littoral Regions of Cameroon

UNIVERSITY OF BUEA FACULTY OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES MARKETS AND MARKET CHAIN ANALYSIS FOR ERU (Gnetum spp.) IN SOUTH WEST AND LITTORAL REGIONS OF CAMEROON BY Ndumbe Njie Louis BSc. (Hons) Environmental Science A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Science of the University of Buea in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Natural Resources and Environmental Management July 2010 ii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the Almighty God who gave me the ability to carryout this project. To my late father Njie Mojemba Maximillian I and my beloved little son Njie Mojemba Maximillian II. iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people: Dr A. F. Nkwatoh, of the University of Buea, for his supervision and guidance; Verina Ingram, of CIFOR, for her immense technical guidance, supervision and support; Abdon Awono, of CIFOR, for guidance and comments; Jolien Schure, of CIFOR, for her comments and field collaboration. I also wish to thank the following organisations: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Netherlands Development Organization (SNV), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the Commission des Forets d‟Afrique Centrale (COMIFAC) for the opportunity to work within their framework and for the team spirit and support. I am also very grateful to the following collaborators: Ewane Marcus of University of Buea; Ghislaine Bongers of Wageningen University, The Netherlands and Georges Nlend of University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland for their collaboration in the field. Thanks also to Agbor Demian of Mamfe. -

The Effect of the Ongoing Civil Strife on Key

Saidu et al. Conflict and Health (2021) 15:8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-021-00341-0 RESEARCH Open Access The effect of the ongoing civil strife on key immunisation outcomes in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon Yauba Saidu1,2* , Marius Vouking3,4, Andreas Ateke Njoh5,6, Hassan Ben Bachire3, Calvin Tonga3, Roberts Mofor7, Christain Bayiha3, Leonard Ewane3, Chebo Cornelius7, Ndi Daniel Daddy Mbida5, Messang Blandine Abizou8, Victor Mbome Njie8,9 and Divine Nzuobontane1 Abstract Background: Civil strife has long been recognized as a significant barrier in the fight against vaccine preventable diseases in several parts of the world. However, little is known about the impact of the ongoing civil strife on the immunisation system in the Northwest (NW) and Southwest (SW) regions of Cameroon, which erupted in late 2016. In this paper, we assessed the effect of the conflict on key immunisation outcomes in the North West and South West regions of Cameroon. Methods: Data were obtained from the standard EPI data reporting tool, the District Vaccine and Data Management Tool (DVDMT), from all the districts in the two regions. Completed forms were then reviewed for accuracy prior to data entry at central level. Summary statistics were used to estimate the variables of interest for each region for the years 2016 (pre-conflict) and 2019 (during conflict). Results: In the two regions, the security situation has deteriorated in almost all districts, which in turn has disrupted basic healthcare delivery in those areas. A total of 26 facilities were destroyed and 11 healthcare workers killed in both regions. -

Climate Variability and Cocoa Production in Meme Division of Cameroon: Agricultural Development Policy Options

Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences ISSN: 2276-7770; ICV: 6.15 Vol. 3 (8), pp. 606-617, August 2013 Copyright ©2017, the copyright of this article is retained by the author(s) http://gjournals.org/GJAS Research Article Climate Variability and Cocoa Production in Meme Division of Cameroon: Agricultural Development Policy options *1Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi and 2Joseph Ngong Tosam 1Pan African Institute for Development West Africa, Buea. 2 Department of Economics and Management, University of Buea, Cameroon. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article No.: 022713505 This study examines the effect of climate variability on cocoa production which is the mainstay of the population of Meme Division. Meme Division stands as one of DOI: 10.15580/GJAS.2013.8.022713505 the highest cocoa producing divisions of the Cameroon. Field studies accompanied by the administration of 155 questionnaires (50 each for Kumba and Mbonge Subdivisions and 55 for Konye Subdivision) were employed. Information on climatic variables (temperature and rainfall) and cocoa output for 21 years Submitted: 27/02/2013 (1990-2010) was also obtained. The data was analyzed with the use of the four point Accepted: 22/08/2013 likert scale survey and the coefficient of variation (CV). The results showed that the Published: 29/08/2013 CV for rainfall (15.1%) and temperature (11.0%) all exceeded the variability threshold of 10% indicating that they exhibit significant variability. Trend analysis *Corresponding Author for cocoa output shows that unusual variations were experienced in some years. This was further confirmed by the Jarque-Bera statistics of 0.68 (P-Value = 0.71) Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi which indicates that the output of cocoa is not normally distributed over time. -

Communal Development Plan for Bangem Council

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace – Work – Fatherland ------------------------ --------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL TERRITORIALE ADMINISTRATION AND ET DE LA DECENTRALISATION DECENTRALISATION -------------------------- ------------------------ REGION DU SUD–OUEST SOUTH WEST REGION DEPARTEMENT DU KOUPE KOUPE MANENGOUBA DIVISION MANENGOUBA ------------------------ ------------------------ BANGEM SUB DIVISION ARRONDISSEMENT DE BANGEM BANGEM COUNCIL COMMUNE DE BANGEM COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR BANGEM COUNCIL JANUARY 30, 2012 Elaborated by the working group composed of: Mr. Ntiege Hans Sumelong, Mr. Nzene Sylvester Enongene, Mr. Motale Moses Sakwe, Mr. Sone Michael Ebune, Mr. Joanes Toulac Jang, Mr. Buh Wong Gaston, Mr. Joseph Mbah, Mr. Joseph Cutler and Miss Mengot Fridah Facilitator COSACODE Kumba, Consultant Financial and technical support Regional Office PNDP South West Project N°: CMR/06/50NET – NICP Cameroon For further information, please kindly contact: At the Bangem Council At PNDP - SW/Cameroon Mr. Ekuh Ojeh Simon Dr. Nkem Mayor Coordinator P O Box 6 Bagem, Cameroon Tel: 237 96309323 Tel: 237 Email: [email protected] Email: Bangem communal development plan – CDP 2012 - 2014 Page 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The present document is a Council Development Plan (CDP) for Bangem Council (BC). It traces the state of development in the Bangem Council Area (BCA) so as to came up with a short term three (3) years development plan. The Bangem Council with financial and technical support from the National Community Driven Participative Program with French acronym (PNDP), and general assistance from COSACODE engaged in the process on 20th July 2011 (date of launching of project). A team put in place by COSACODE and the Bangem Council organized a training session for 24 local facilitators to facilitate the participative territorial diagnosis, institutional diagnosis, council diagnosis, village vital data collection.