MIGRATION and IDENTITY in SOUTHWEST REGION of CAMEROON: the GRAFFIE FACTOR, C.1930S-1996

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

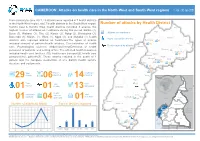

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon

sustainability Article Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon Akhere Solange Gwan 1 and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi 2,3,* 1 Department of Geography and Planning, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Technische Universität Dresden, 01737 Tharandt, Germany 3 Department of Geography, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 14 July 2020; Published: 18 July 2020 Abstract: There is growing interest in the need to understand the link between urban expansion and farmers’ livelihoods in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including Cameroon. This paper undertakes a qualitative investigation of the effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods in Bamenda, a primate city in Cameroon. Taking into consideration two key areas—the Mankon–Bafut axis and the Nkwen Bambui axis—this study analyzes the trends and effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods with a view to identifying ways of making the process more beneficial to the farmers. Maps were used to determine the trend of urban expansion between 2000 and 2015. Twelve farmers drawn from the target sites were interviewed, while three focus group discussions were conducted. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze perceptions of the effects and coping strategies of farmers to urban expansion. Using the livelihoods approach, farmers’ livelihoods repertoires and portfolios were analyzed for the periods before and after urban expansion. Between 2000 and 2015, the surface area for farmlands in Bamenda II and Bamenda III reduced from 3540 ha to 2100 ha and 2943 ha to 1389 ha, respectively. -

Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon

Centre for Research on Settlements and Urbanism Journal of Settlements and Spatial Planning J o u r n a l h o m e p a g e: http://jssp.reviste.ubbcluj.ro Human Settlement Dynamics in the Bamenda III Municipality, North West Region, Cameroon Lawrence Akei MBANGA 1 1 The University of Bamenda, Faculty of Arts, Department of Geography and Planning, Bamenda, CAMEROON E-mail: [email protected] DOI: 10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 https://doi.org/10.24193/JSSP.2018.1.05 K e y w o r d s: human settlements, dynamics, sustainability, Bamenda III, Cameroon A B S T R A C T Every human settlement, from its occupation by a pioneer population continues to undergo a process of dynamism which is the result of socio economic and dynamic factors operating at the local, national and global levels. The urban metabolism model shows clearly that human settlements are the quality outputs of the transformation of inputs by an urban area through a metabolic process. This study seeks to bring to focus the drivers of human settlement dynamics in Bamenda 3, the manifestation of the dynamics and the functional evolution. The study made used of secondary data and information from published and unpublished sources. Landsat images of 1989, 1999 and 2015 were used to analyze dynamics in human settlement. Field survey was carried out. The results show multiple drivers of human settlement dynamism associated with population growth. Human settlement dynamics from 1989, 1999 and 2015 show an evolution in surface area with that of other uses like agriculture reducing. -

Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon

Aging Medicine and Healthcare 2020;11(1):10-19. doi:10.33879/AMH.2020.033-1904.010 Aging Medicine and Healthcare https://www.agingmedhealthc.com Original Article Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon *Agbor Nathan Emeh1,2, Fongang Che Landis1,3, Tambetakaw Njang Gilbert1,2, Atongno Ashu Humphrey1,2 1University of Buea, Cameroon 2Ministry of Public Health, Yaounde, Cameroon 3Cameroon Christian University, Cameroon ABSTRACT Background/Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the socio- clinical profile, heath status and determine the impact of age on health related behaviors of geriatric population in the Buea Health District. Since studies on the subject are lacking in Cameroon, we believe this study provides ground work for further studies on geriatrics in Cameroon. Methods: Two-stage systematic sampling was used. Firstly, 30 communities of the Buea Health District were randomly selected. Eligible participants in these communities were then selected in turns. Interviewer-administered questionnaire, physical examination and health record checks were used to capture the study objectives. Results: Of the 142 sampled elderlies, 57.7% (82/142) were females with the young-old (60-75 years) constituted the majority (69.01%; 98/142). Most of the elderlies (88%; 125/142) had at least one chronic disease, 35.9% (51/142) had *Correspondence at least two and 9.86% (14/142) had at least three chronic diseases. The major Dr. Agbor Nathan Emeh chronic diseases suffered by elderlies included arthritis (38.73%; 55/142), gastritis (38.73%; 55/142) and hypertension (29.58%; 42/142). Most affected Department of Public Health body systems were musculoskeletal (86.62%; 123/142), neurologic (85.21%; and Hygiene, University of 121/142), and eye (76.76%; 109/142). -

SSA Infographic

CAMEROON: Attacks on health care in the North-West and South-West regions 1 Jan - 30 Jun 2021 From January to June 2021, 29 attacks were reported in 7 health districts in the North-West region, and 7 health districts in the South West region. Number of attacks by Health District Kumbo East & Kumbo West health districts recorded 6 attacks, the Ako highest number of attacks on healthcare during this period. Batibo (4), Wum Buea (3), Wabane (3), Tiko (2), Konye (2), Ndop (2), Benakuma (2), Attacks on healthcare Bamenda (1), Mamfe (1), Wum (1), Nguti (1), and Muyuka (1) health Injury caused by attacks Nkambe districts also reported attacks on healthcare.The types of attacks Benakuma 01 included removal of patients/health workers, Criminalization of health 02 Nwa Death caused by attacks Ndu care, Psychological violence, Abduction/Arrest/Detention of health Akwaya personnel or patients, and setting of fire. The affected health resources Fundong Oku Kumbo West included health care facilities (10), health care transport(2), health care Bafut 06 Njikwa personnel(16), patients(7). These attacks resulted in the death of 1 Tubah Kumbo East Mbengwi patient and the complete destruction of one district health service Bamenda Ndop 01 Batibo Bali 02 structure and equipments. Mamfe 04 Santa 01 Eyumojock Wabane 03 Total Patient Healthcare 29 Attacks 06 impacted 14 impacted Fontem Nguti Total Total Total 01 Injured Deaths Kidnapping EXTRÊME-NORD Mundemba FAR-NORTH CHAD 01 01 13 Bangem Health Total Ambulance services Konye impacted Detention Kumba North Tombel NONORDRTH 01 04 destroyed 01 02 NIGERIA Bakassi Ekondo Titi Number of attacks by Month Type of facilities impacted AADAMAOUADAMAOUA NORTH- 14 13 NORD-OUESTWEST Kumba South CENTRAL 12 WOUESTEST AFRICAN Mbonge SOUTH- SUD-OUEST REPUBLIC 10 WEST Muyuka CCENTREENTRE 8 01 LLITITTORALTORAL EASESTT 6 5 4 4 Buea 4 03 Tiko 2 Limbe Atlantic SSUDOUTH 1 02 Ocean 2 EQ. -

The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: a Geopolitical Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal December 2019 edition Vol.15, No.35 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 The Anglophone Crisis in Cameroon: A Geopolitical Analysis Ekah Robert Ekah, Department of 'Cultural Diversity, Peace and International Cooperation' at the International Relations Institute of Cameroon (IRIC) Doi:10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/esj.2019.v15n35p141 Abstract Anglophone Cameroon is the present-day North West and South West (English Speaking) regions of Cameroon herein referred to as No-So. These regions of Cameroon have been restive since 2016 in what is popularly referred to as the Anglophone crisis. The crisis has been transformed to a separatist movement, with some Anglophones clamoring for an independent No-So, re-baptized as “Ambazonia”. The purpose of the study is to illuminate the geopolitical perspective of the conflict which has been evaded by many scholars. Most scholarly write-ups have rather focused on the causes, course, consequences and international interventions in the crisis, with little attention to the geopolitical undertones. In terms of methodology, the paper makes use of qualitative data analysis. Unlike previous research works that link the unfolding of the crisis to Anglophone marginalization, historical and cultural difference, the findings from this paper reveals that the strategic location of No-So, the presence of resources, demographic considerations and other geopolitical parameters are proving to be responsible for the heightening of the Anglophone crisis in Cameroon and in favour of the quest for an independent Ambazonia. -

Li.I I:L Li.I Li.I

• zI- LI.I ~ I:L 9 LI.I >LI.I Q EUROPEAN COMMISSION DE 90 . February , 1997 _1&tl~~2~. The Cameroonian Economy II Cameroon in Figures II er.BIl1!lmr'qlt~_e.~t§'~~g~i'§j"~]fgm From the Treaty of Rome to the Lome Convention Lome IV IJ Lome IV II The Institutions of the European Union .• The Instruments of Cooperation II The European Development Fund II ACP States and the European Union Il!J ~A_~~~11l~Ei9.~M~r~ Trade Relations m Bilateral Cooperation with the Member States lEI Commuriications Infrastructure lEI Road Maintenance Programme II Social Services II Health Education ~~/¥W#@Muar~~ .1!i9Jjt~J!}.Bti~.!t~~~m A NewPolicy II] The EC's Contribution to Privatization 1m Restructuring the Coffee and Cocoa Sectors Em AgricLiltlir~ m .. .... ,'. R~raldevEiJoPrT1e~(m, RJraioevelopment CentreProjed ,North-East Benoue Prbj~ct . .. ...•. .• '.. '" .• ' .•. .....STABEX TheCRBP and SupportforAgronOmy Research it) Central Africa ~fiiG~_~QR~.rx~~ EnVironment and Biodivd~Sity '1:9!1. O'therAid ~ Aid to Non"Governmental OrMnizations RegionalJ:ooperation' m MiJin Community Projects in Cameroon With map' Em CommunitY Operations in Cameroon 1960-95 1m Cover: Infrastructure. medical research and cattle breeding are all areas facing difficult challenges iri.the changing economic environm~~t. (REAphoto + Commission Delegation - Yaoynde) Introduction ooperation between Europe and Cameroon, \vhich was first established in 1958, has always been carefully Cattuned to Cameroon's development priorities. Traditional technical and financial cooperation under the Conventions between the African, Caribbean and Pacific States and the European Community, the first of which, Yaounde I, was signed in the Cameroonian capital in 1963, has gone hand in-hand with an expansion in trade between the t\VO sides. -

African Development Bank Group

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT : TRANSPORT SECTOR SUPPORT PROGRAMME PHASE 2 : REHABILITATION OF YAOUNDE-BAFOUSSAM- BAMENDA ROAD – DEVELOPMENT OF THE GRAND ZAMBI-KRIBI ROAD – DEVELOPMENT OF THE MAROUA-BOGO-POUSS ROAD COUNTRY : REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON SUMMARY FULL RESETTLEMENT PLAN (FRP) Team Leader J. K. NGUESSAN, Chief Transport Engineer OITC.1 P. MEGNE, Transport Economist OITC.1 P.H. SANON, Socio-Economist ONEC.3 M. KINANE, Environmentalist ONEC.3 S. MBA, Senior Transport Engineer OITC.1 T. DIALLO, Financial Management Expert ORPF.2 C. DJEUFO, Procurement Specialist ORPF.1 Appraisal Team O. Cheick SID, Consultant OITC.1 Sector Director A. OUMAROU OITC Regional Director M. KANGA ORCE Resident CMFO R. KANE Representative Sector Division OITC.1 J.K. KABANGUKA Manager 1 Project Name : Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2 SAP Code: P-CM-DB0-015 Country : Cameroon Department : OITC Division : OITC-1 1. INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of the Abbreviated Resettlement Plan (ARP) of the Transport Sector Support Programme Phase 2. The ARP was prepared in accordance with AfDB requirements as the project will affect less than 200 people. It is an annex to the Yaounde- Bafoussam-Babadjou road section ESIA summary which was prepared in accordance with AfDB’s and Cameroon’s environmental and social assessment guidelines and procedures for Category 1 projects. 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION, LOCATION AND IMPACT AREA 2.1.1 Location The Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda road covers National Road 4 (RN4) and sections of National Road 1 (RN1) and National Road 6 (RN6) (Figure 1). The section to be rehabilitated is 238 kilometres long. Figure 1: Project Location Source: NCP (2015) 2 2.2 Project Description and Rationale The Yaounde-Bafoussam-Bamenda (RN1-RN4-RN6) road, which was commissioned in the 1980s, is in an advanced state of degradation (except for a few recently paved sections between Yaounde and Ebebda, Tonga and Banganté and Bafoussam-Mbouda-Babadjou). -

Ownership, Coverage, Utilisation and Maintenance of Long

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/465005; this version posted February 20, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Ownership, Coverage, Utilisation and Maintenance of Long-lasting insecticidal nets in Three Health Districts in Cameroon: A Cross- Sectional Study Frederick Nchang Cho1,2,3, Paulette Ngum Fru4,5, Blessing Menyi Cho6, Solange Fri Munguh6, Patrick Kofon Jokwi6,7, Yayah Emerencia Ngah8, Celestina Neh Fru9,10, Andrew N Tassang10,11,12, Peter Nde Fon4,13, Albert Same Ekobo14,15 1Global Health Systems Solutions, Cameroon. 2Infectious Disease Laboratory, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 3Central African Network for Tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS and Malaria (CANTAM), University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 4Department of Public Health and Hygiene, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 5District Health Service Tiko, South West Regional Delegation of Health, Ministry of Health, Cameroon. 6Catholic School of Health Sciences, Saint Elizabeth Hospital Complex, P.O. Box 8 Shisong-Nso, Cameroon. 7Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board (CBCHB) – HIV Free Project, Kumbo-Cameroon. 8District Hospital Bali, Ministry of Public Health, Cameroon. 9Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 10Atlantic Medical Foundation, Mutengene-Cameroon. 11Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Buea, Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon. 12Buea Regional Hospital Annex, Cameroon. 13Solidarity Hospital, Buea-Cameroon. 14Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Douala, Cameroon. 15Parasitology Laboratory, University Hospital Centre of Yaoundé, Cameroon.