The Effect of the Ongoing Civil Strife on Key

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (Geneva, Switzerland)

To Permanent Representatives of Member and Observer States of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council (Geneva, Switzerland) 12 May 2021 Multilateral action is needed to address the human rights crisis in Cameroon Excellencies, We, the undersigned civil society organisations, are deeply concerned over ongoing grave human rights violations and abuses in Cameroon. Ahead of the Human Rights Council’s (“HRC” or “Council”) 47th session (21 June-15 July 2021), we urge your delegation to support multilateral action to address Cameroon’s human rights crisis in the form of a joint statement to the Council. This statement should include benchmarks for progress, which, if fulfilled, will constitute a path for Cameroon to improve its situation. If these benchmarks remain unfulfilled, then the joint statement will pave the way for more formal Council action, including, but not limited to, a reso- lution establishing an investigative and accountability mechanism. Over the last four years, civil society organisations have called on the Government of Cameroon, armed separatists, and other non-state actors to bring violations and abuses1 to an end. Given Cameroonian institutions’ failure to deliver justice and accountability, civil society has also called on African and international human rights bodies and mechanisms to investigate, monitor, and publicly report on Ca- meroon’s situation. Enhanced attention to Cameroon, on the one hand, and dialogue and cooperation, on the other, are not mutually exclusive but rather mutually reinforcing. They serve the same objective: helping the Came- roonian Government to bring violations to an end, ensure justice and accountability, and fulfil its human rights obligations. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

(Fsw) and Men Who Have Sex with Men (Msm) in Burkina Faso, Togo and Cameroon

EXAMINING RISK FACTORS FOR HIV AND ACCESS TO ServICES AMONG FEMALE SEX WORKerS (FSW) AND MEN WHO HAve SEX WITH MEN (MSM) IN BURKINA FASO, TOGO AND CAMerOON EXAMINING RISK FACTORS FOR HIV AND ACCESS TO SERVICES AMONG FEMALE SEX WORKERS (FSW) AND MEN WHO HAVE SEX WITH MEN (MSM) IN BURKINA FASO, TOGO AND CAMEROON March 2014 Authors: Erin Papworth, Ashley Grosso, Sosthenes Ketende, Andrea Wirtz, Charles Cange, Caitlin Kennedy, Matthew Lebreton, Odette Ky-Zerbo, Simplice Anato, Stefan Baral The USAID | Project SEARCH, Task Order No.2, is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Contract No. GHH-I-00-07-00032-00, beginning September 30, 2008, and supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The Research to Prevention (R2P) Project is led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health and managed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs (CCP). Examining Risk Factors for HIV and Access to Services among KP in West Africa ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The study was implemented by USAID | Project SEARCH, Task Order No. 2: Research to Prevention (R2P). R2P is based at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Stefan Baral with the R2P team at JHU designed the study and provided technical assistance during its implementation. In Burkina Faso, the study was implemented by the Programme d’Appui au Monde Associative et Communautaire de lute contre le VIH/SIDA, la tuberculose et le paludisme (PAMAC) in close partnership with l’Institut de Recherche en Sciences de la Santé (IRSS). In Togo, the study was implemented by Espoir-Vie Togo (EVT) in close partnership with Arc en Ciel and Force en Action pour le Mieux être de la Mère et de l'Enfant (FAMME). -

GEF Prodoc TRI Cameroon 28 02 18

International Union for the Conservation of Nature Country: Cameroon PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: Supporting Landscape Restoration and Sustainable Use of local plant species and tree products (Bambusa ssp, Irvingia spp, etc) for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Livelihoods and Emissions Reduction in Cameroon BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT The Republic of Cameroon has a diverse ecological landscape, earning her the title “Africa in Miniature”. The southern portions of Cameroon’s forests are part of the Congo Basin forest ecosystem, the second largest remaining contiguous block of rainforest on Earth, after the Amazon. In addition to extensive Mangrove belts, Cameroon also holds significant portions of the Lower Guinea Forest Ecosystems and zones of endemism extending into densely settled portions of the Western Highlands and Montagne forests. The North of the country comprising the Dry Sudano-Sahelian Savannah Zones is rich in wildlife, and home to dense human and livestock populations. Much of the population residing in these areas lives in extreme poverty. This diversity in biomes makes Cameroon one of the most important and unique hotspots for biodiversity in Africa. However, human population growth, migrations, livelihoods strategies, rudimentary technologies and unsustainable land use for agriculture and small-scale forestry, energy and livestock, are contributing to biodiversity loss and landscape degradation in Cameroon. Despite strong institutional frameworks, forest and environmental policies/legislation, and a human resource capital, Cameroon’s network of biomes that include all types of forests, tree-systems, savannahs, agricultural mosaics, drylands, etc., are progresively confronted by various forms of degradation. Degradation, which is progressive loss of ecosystem functions (food sources, water quality and availability, biodversity, soil fertility, etc), now threatens the livelihoods of millions of Cameroonians, especially vulnerable groups like women, children and indigenous populations. -

CAMEROON Perspectives on Food Security October 2020 to May 2021 Food Security Improved in the Far North, but Worsened in the Northwest and Southwest

CAMEROON Perspectives on food security October 2020 to May 2021 Food security improved in the Far North, but worsened in the Northwest and Southwest KEY MESSAGES • Despite the recent surge in attacks by Boko Haram, and Current food security situation, October 2020 excessive rainfall leading to flooding in some locations in the Far North, ongoing new harvests have improved food security for many poor households that currently subsist on their own harvests. The harvest of rainfed grains from the primary agricultural campaign in 2020 is estimated to be average, due to favorable weather conditions. Slightly lower than average production is expected in the Logone-et-Chari, Mayo Sava, and Mayo Tsanga departments, where Boko Haram is most active, as well as in locations where harvests were lost to flooding. • Current prices at the primary markets in the Far North appear stable or are decreasing. Since July 2020, staple food prices have increased above typical levels. Sorghum and maize are selling at 46 to 60 percent, and 30 to 47 percent higher (respectively) than in July 2019. Although current prices are still above average, sorghum and groundnut prices have decreased by 17 percent and 18 percent as compared to the Source: FEWS NET previous three months. FEWS NET classification is IPC-compatible (Integrated Phase Classification). IPC-compatible analysis follows key IPC protocols but • In the Northwest and Southwest regions, where agricultural does not necessarily reflect the consensus of national food security production was lower than average for four consecutive years partners. due to ongoing socio-political conflicts, this year's harvests are running out earlier than usual. -

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°143 Nairobi /Brussels, 14 January 2019 What’s new? Protests across Sudan flared up as the government cut a vital bread subsidy. Economic grievances are fuelling demands for political change, with protest- ers calling on President Omar al-Bashir, in power since 1989, to resign. Authorities have responded with violence, killing dozens and arresting many more. Why does it matter? In the past, President Bashir and his government have been able to ride out popular demonstrations. But these newest protests, demanding Bashir resign because of economic mismanagement and corruption, have spread to loyalist regions and coincide with rising discontent in his party. What should be done? Foreign governments influential in Khartoum should continue to publicly discourage violence against demonstrators, with Western pow- ers signalling that future aid and, in the U.S.’s case, sanctions relief are at stake. They should seek to improve prospects for a peaceful transition by creating incentives for Bashir to step down. I. Overview Protests engulfing Sudanese towns and cities have seen dozens killed in crackdowns by security forces and could turn bloodier still. Demonstrators express fury over sub- sidy cuts and call for President Omar al-Bashir to resign. Discontent within the ruling party, the depth of the economic crisis and the diverse makeup of protests suggest Bashir has less room to manoeuvre than before. He may survive, though likely by suppressing protests with levels of violence that would reverse his recent rapproche- ment with Western powers and deepen Sudan’s economic woes. -

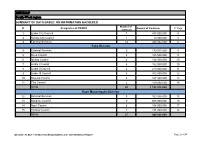

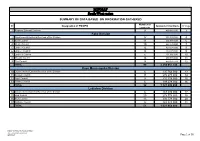

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

“Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: the Central African Republic and South Sudan

al Science tic & li P o u P b f l i o c l A a f Journal of Political Sciences & Public n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Affairs Review Article “Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: The Central African Republic and South Sudan Agberndifor Evaristus Department Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Civil wars are not new and they predate the modern nation states. From the time when nations gathered in well- defined or near defined geographical locations, there has always been internal wrangling between the citizens and the state for reasons that might not be very different from place to place. However, the tensions have always mounted up such that people took to the streets first to protest and sometimes, the immaturity of the government to listen to the demands of the people radicalized them for bloodshed. This paper shall empirically examine the cause of civil wars in Sub-Saharan Africa having at the back of its thoughts that civil wars are most times associated to political, economic and ethnic incentives. This paper shall try in empirical terms using data from already established research to prove these points. Firstly, it shall explain its independent variables which apparently are some underlying causes of civil wars. Secondly, it shall consider the dense literature review of civil wars and shall look at some definitions, theories of civil wars and data presented on a series of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, it shall isolate two countries that will make up its comparative analysis and the explanations of its dependent variable by which it shall seek to understand what caused the outbreaks of civil wars in those two countries.