An Interdisciplinary Journal Youth and Currency Counterfeiting At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • From 25-27 April, Marie-Pierre Poirier, UNICEF Regional Director April 2018 for West and Central Africa Region visited projects in the Far North and East regions to evaluate the humanitarian situation 1,810,000 # of children in need of humanitarian and advocated for the priorities for children, including birth assistance registrations. 3,260,000 • UNHCR and UNICEF with support of WFP donated 30 tons of non- # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) food items including soaps to be distributed in Mamfe and Kumba sub-divisions in South West region for estimated 23,000 people Displacement affected by the Anglophone crisis. 241,000 • As part of the development of an exit strategy for Temporary #of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) Learning and Protective Spaces (TLPSs), a joint mission was 69,700 conducted to verify the situation of 87 TLPSs at six refugee sites # of Returnees and host community schools in East and Adamaoua regions. The (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) 93,100 challenge identified is how to accommodate 11,314 children who # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas are currently enrolled in the TLPSs into only 11 host community (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) 238,700 schools, with additional 7,325 children (both IDPs and host # of CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and community) expected to reach the school age in 2018. North regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, April 2018) UNICEF’s Response with Partners UNICEF Appeal 2018 Sector UNICEF US$ 25.4 million Sector Total UNICEF Total Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH : People provided with 528,000 8,907 75,000 8,907 US$ 2.1 m access to appropriate sanitation Funds Education: School-aged children 4- received 17, including adolescents, accessing 411,000 11,314 280,000 11,314 US$ 1.8 m education in a safe and protective learning environment. -

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Fako : Village Dictionary of Fako Division

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIOUE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE· MER Il REPUBLIQUE UNIE DU CAMEROUN DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION SECTION DE GEOGRAPHIE 1 OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE SCIm~TIFIQUE REPUBLIQUE UNIE ET TECmUQUE OUTRE-lViER DU CAlvŒROUN UNITED REPUBLIC OF CANEROON CENTRE O.R.S.T.O.N DE YAOUNDE DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES DU FAKO VILLAGE DICTIONARY OF FAKO DIVISION Juillet 1973 July 1973 COPYRIGHT O.R.S.T.O.M 1973 TABLE DES NATIERES CONTENTS i l j l ! :i i ~ Présentation •••••.•.•.....••....•.....•....••••••.••.••••••.. 1 j Introduction ........................................•• 3 '! ) Signification des principaux termes utilisés •.............• 5 î l\lIeaning of the main words used Tableau de la population du département •...••.....•..•.•••• 8 Population of Fako division Département du Fako : éléments de démographie •.•.... ..••.•• 9 Fako division: demographic materials Arrondissements de Muyuka et de Tiko : éléments de . démographie 0 ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 10 11uyul{a and Tileo sl)..bdivisions:demographic materials Arrondissement de Victoria: éléments de démographie •••.••• 11 Victoria subdivision:demographic materials Les plantations (12/1972) •••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Plantations (12/1972) Liste des villages par arrondissement, commune et graupement 14 List of villages by subdivision, area council and customary court Signification du code chiffré •..•••...•.•...•.......•.•••.• 18 Neaning of the code number Liste alphabétique des villages ••••••.••••••••.•.•..•••.•.• 19 -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

MINMAP South-West Region

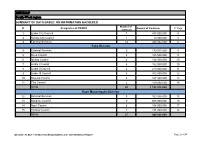

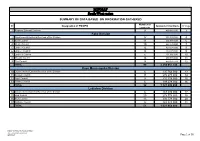

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

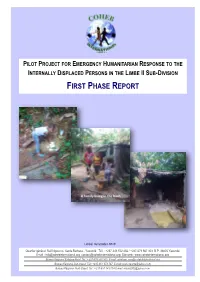

First Phase Report

Page 1 PILOT PROJECT FOR EMERGENCY HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE TO THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN THE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION FIRST PHASE REPORT A family living in the bush Limbé, December 2018 Quartier général: Rail Ngousso- Santa Barbara - Yaoundé Tél. : +237-243 572 456 / +237-679 967 303 B.P. 33805 Yaoundé Email : [email protected] [email protected] Site web : www.cohebinternational.org Bureau Régional Extrême-Nord: Tél.: +237-674 900 303 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Sud-Ouest: Tél.: +237-651 973 747 E-mail: [email protected] Bureau Régional Nord-Ouest: Tél.: +237-697 143 004 E-mail: [email protected] Emergency response to Limbe II IDPs - December 2018 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENT PRESENTATION OF COHEB INT’L ................................................................. 3 SOME OF OUR EMERGENCY ACTIVITIES ......................................................... 4 CONTEXT OF THE PROJECT .......................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVE OF THE PROJECT ........................................................................ 6 EXECUTION OF THE PROJECT .................................................................... 7-9 CONCLUSION ............................................................................................ 10 ANNEX 1: IDP’S SETTLEMENT CAMP MUKUNDANGE LIMBE II SUB-DIVISION......................................................... 11 ANNEX 2: COHEB PROJECT OFFICE SOKOLO, LIMBE II OUR AGRO-FORESTRY TRANSFORMATION FACTORY AND LOGISTICS -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon

Aging Medicine and Healthcare 2020;11(1):10-19. doi:10.33879/AMH.2020.033-1904.010 Aging Medicine and Healthcare https://www.agingmedhealthc.com Original Article Health Status of Elderly Population in the Buea Health District, Cameroon *Agbor Nathan Emeh1,2, Fongang Che Landis1,3, Tambetakaw Njang Gilbert1,2, Atongno Ashu Humphrey1,2 1University of Buea, Cameroon 2Ministry of Public Health, Yaounde, Cameroon 3Cameroon Christian University, Cameroon ABSTRACT Background/Purpose: The purpose of this study was to assess the socio- clinical profile, heath status and determine the impact of age on health related behaviors of geriatric population in the Buea Health District. Since studies on the subject are lacking in Cameroon, we believe this study provides ground work for further studies on geriatrics in Cameroon. Methods: Two-stage systematic sampling was used. Firstly, 30 communities of the Buea Health District were randomly selected. Eligible participants in these communities were then selected in turns. Interviewer-administered questionnaire, physical examination and health record checks were used to capture the study objectives. Results: Of the 142 sampled elderlies, 57.7% (82/142) were females with the young-old (60-75 years) constituted the majority (69.01%; 98/142). Most of the elderlies (88%; 125/142) had at least one chronic disease, 35.9% (51/142) had *Correspondence at least two and 9.86% (14/142) had at least three chronic diseases. The major Dr. Agbor Nathan Emeh chronic diseases suffered by elderlies included arthritis (38.73%; 55/142), gastritis (38.73%; 55/142) and hypertension (29.58%; 42/142). Most affected Department of Public Health body systems were musculoskeletal (86.62%; 123/142), neurologic (85.21%; and Hygiene, University of 121/142), and eye (76.76%; 109/142). -

Governance of Disaster Risk Reduction in Cameroon: the Need to Empower Local Government

Page 1 of 10 Original Research Governance of disaster risk reduction in Cameroon: The need to empower local government Author: The impact of natural hazards and/or disasters in Cameroon continues to hit local communities 1,2 Henry N. Bang hardest, but local government lacks the ability to manage disaster risks adequately. This Affiliations: is partly due to the fact that the necessity to mainstream disaster risk reduction into local 1African Centre for Disaster governance and development practices is not yet an underlying principle of Cameroon’s Studies, Potchefstroom, disaster management framework. Using empirical and secondary data, this paper analyses South Africa the governance of disaster risks in Cameroon with particular focus on the challenges local 2School of International government faces in implementing disaster risk reduction strategies. The hypothesis is that Development, University the governance of disaster risks is too centralised at the national level, with huge implications of East Anglia, Norwich, for the effective governance of disaster risks at the local level. Although Cameroon has United Kingdom reinvigorated efforts to address growing disaster risks in a proactive way, it is argued that Correspondence to: the practical actions are more reactive than proactive in nature. The overall aim is to explore Henry Bang the challenges and opportunities that local government has in the governance of disaster risks. Based on the findings from this research, policy recommendations are suggested on Email: ways to mainstream disaster risk reduction strategies into local governance, and advance [email protected] understanding and practice in the local governance of disaster risks in the country. Postal address: 37 Whitworth Court, Norwich, NR6 6GN, United Kingdom Introduction Natural hazards continue to pose a major threat to the entire world with prospects of even greater Dates: impacts to life and property in the future (Aini & Fakhrul-Razi 2010; Hayles 2010). -

“These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’S WATCH Anglophone Regions

HUMAN “These Killings Can Be Stopped” RIGHTS Government and Separatist Groups Abuses in Cameroon’s WATCH Anglophone Regions “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36352 “These Killings Can Be Stopped” Abuses by Government and Separatist Groups in Cameroon’s Anglophone Regions Map .................................................................................................................................... i Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Mundemba Communal Development Plan

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN --------- ------------ Peace – Work – Fatherland Paix – Travail – Patrie ---------- ----------- MINISTRY OF ECONOMY, PLANNING AND MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DE LA PLANIFICATION REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT ET DE L’AMENAGEMENT DU TERRITOIRE ---------- ------------- GENERAL SECRETARY SECRETARIAT GENERAL ---------- ------------ NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME NATIONAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT PROGRAM PARTICIPATIF ---------- ------------ SOUTHWEST REGIONAL COORDINATION UNIT CELLULE REGIONALE DE COORDINATION DE SUD ------------ OUEST ------------ MUNDEMBA COMMUNAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN June 2011 i Table of Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF ABBREVIATION ................................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................................. viii LIST OF FIGURE .................................................................................................................................................... ix LIST OF MAPS ........................................................................................................................................................ ix LIST OF ANNEXES ...............................................................................................................................................