Texas Motor Speedway: Print Advertising, Sponsorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

2021 Nascar Cup Series

2021 NASCAR CUP SERIES DAY DATE TRACK LOCATION EVENT START TIME SUN 2/21 NCS Daytona Int’l Speedway Rd Course NCS at Daytona Road Course 2:00 PM SUN 2/28 NCS Homestead-Miami Speedway Dixie Vodka 400 2:30 PM SUN 3/7 NCS Las Vegas Motor Speedway Pennzoil 400 2:30PM SUN 3/14 NCS Phoenix Raceway NCS at Phoenix 2:30 PM SUN 3/21 NCS Atlanta Motor Speedway Folds of Honor QT 500 2:00PM SUN 3/28 NCS Bristol Motor Speedway-DIRT Food City 500 2:30PM SAT 4/10 NCS Blue Emu Max Pain Relief 500 Martinsville Speedway 7:30PM SUN 4/18 NCS Richmond Raceway Toyota Owners 400 2:00 PM SUN 4/25 NCS Talladega Superspeedway GEICO 500 1:00 PM SUN 5/2 NCS Kansas Speedway NCS at Kansas 2:00 PM SUN 5/9 NCS Darlington Raceway NCS at Darlington 2:30 PM SAT 5/15 INDY Indianapolis Motor Speedway Indy Motor Speedway Road Course 2:30PM SUN 5/16 NCS Dover Int’l Speedway Drydene 400 1:00 PM SUN 5/23 NCS Circuit of the Americas PRN TBD 1:30PM SUN 5/30 INDY Indianapolis Motor Speedway Indy 500 11:00AM SUN 5/30 NCS Charlotte Motor Speedway Coca-Cola 600 5:00PM SAT 6/6 NCS Sonoma Raceway Toyota/Save Mart 350 3:00PM SUN 6/13 NCS Texas Motor Speedway NASCAR All-Star Race 5:00 PM SUN 6/20 NCS Nashville Speedway NCS at Nashville 2:30 PM SAT 6/26 NCS Pocono Raceway NCS at Pocono-1 2:00 PM SUN 6/27 NCS Pocono Raceway NCS at Pocono-2 2:30 PM SUN 7/4 NCS Road America (WI) NCS at Road America 1:30 PM SUN 7/11 NCS Atlanta Motor Speedway Quaker State 400 2:30PM SUN 7/18 NCS New Hampshire Motor Speedway Foxwoods Resort Casino 301 2:00PM SUN 8/8 NCS Watkins Glen Int’l Go Bowling at the Glen -

HEMI Milestones

Contact: General Media Inquiries Bryan Zvibleman HEMI® Milestones A Journey through a Remarkable Engine’s Remarkable History August 10, 2005, Auburn Hills, Mich. - 1939 Chrysler begins design work on first HEMI®, a V-16 for fighter aircraft. 1951 Chrysler stuns automotive world with 180 hp HEMI V-8 engine. Chrysler New Yorker convertible paces Indianapolis 500 race. Saratoga first in Stock Car Class; second overall in Carrera Pan-American road race. Briggs Cunningham chooses HEMI engines for his Le Mans race cars. 1952 A special HEMI is tested in a Kurtis Kraft Indy roadster; it’s banned by racing officials as too fast. 1953 Lee Petty’s HEMI Dodge wins five NASCAR races and finishes second in championship points. Cunningham’s C-4R HEMI wins 12 Hours of Sebring and finishes third at Le Mans. A Dodge HEMI V-8 breaks 196 stock car records at Bonneville Salt Flats. 1954 A Chrysler HEMI with four-barrel and dual exhausts makes 235 hp. Lee Petty wins Daytona Beach race in a Chrysler HEMI. Lee Petty wins NASCAR Grand National championship driving Chrysler and Dodge HEMIs. Cunningham HEMIs win Sebring again, third and fifth at Le Mans. Dodge Red Ram HEMI convertible paces Indy 500. 1955 Chrysler introduces the legendary 300 as America’s most powerful stock car. Chrysler 300 with dual four-barrel 331 c.i.d. HEMI is first production car to make 300 hp. A Carl Kiekhaefer-prepared Chrysler 300 wins at Daytona Beach with Tim Flock driving. Chrysler bumps HEMI to 250 hp in New Yorker and 280 hp in Imperial. -

Buick Club of America Volume XXXVI No

1968 Buick Electra 225 owned by Steve Dodson Monthly Newsletter of the St Louis Chapter Buick Club of America Volume XXXVI No. 7 July 2017 Hi All … I hope everyone is having a great summer so far. I am always frank and honest…and this month’s director’s letter is an urgent call for our club to step up and help. Guys and gals… we are in desperate need to sell our trophy classes for the Shriners Benefit Car Show. We are less than 3 months away and have sold only 15 of our 32 classes. Richard Self has volunteered to revisit last GATEWAY GAZETTE 1 year’s contacts made by Doug Stahl, and Mark Kistner is following up on some leads. If we cannot sell these classes, we will not be able to pay for trophies this year. We really need everyone to step up to make this come together. Doug Stahl went to businesses that he frequented regularly… is there a business you visit that may want to contribute? Are your co-workers generous? Maybe have people poll $5.00 each together to sponsor a class. If everyone just asks a few businesses… we will be able to make this come together in time for the show. I have sold three classes and have been busy working on attendance prizes and raffle baskets. On my annual car trip I received verbal confirmation from Mothers and Laid Back for items again this year. I will also be visiting FastLane Cars and EPC Computers next week. September will be here before we know it. -

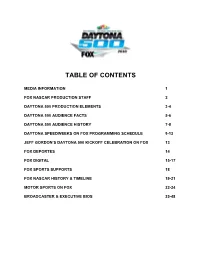

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

2021 Credential Policy

2021 CREDENTIAL POLICY INDYCAR welcomes and appreciates at-track coverage from accredited members of the media. Media credentials for each NTT INDYCAR SERIES event are issued by that respective event’s track or promoter. Credential contacts for all 12 NTT INDYCAR SERIES venues are listed below as well as in the Tracks section of the 2021 NTT INDYCAR SERIES Media Guide. INDYCAR issues annual credentials (hard cards) to media covering a substantial number of races. Hard card media MUST contact the individual racetrack to request media center access, parking passes and any other special needs. Barber Motorsports Park Visit https://barberracingevents.com/ to request credentials. Only credentials submitted via the online request form will be considered. Credential Office Location: Hampton Inn, 310 Rex Lake Road, Birmingham, AL 35094 Streets of St. Petersburg Applications for media credentials are available on the MEDIA page at www.gpstpete.com. Credential Office Location: Rococo Steak, 655 2nd Ave S, St. Petersburg, FL 33701 Texas Motor Speedway No written or fax requests please; all credential requests are processed online at www.smicredentials.com; deadline is three weeks prior to the event. Credential Office Location: Trailer behind the ticket office/gift shop building near the lake on property. Indianapolis Motor Speedway Please send requests on company letterhead signed by the assigning editor to: IMS Media Credentials P.O. Box 24906 Indianapolis, IN 46224 Credential Office Location: Administration Building located at the corner of 16th & Georgetown Road. Raceway at Belle Isle Park Visit www.detroitgp.com to download media credential request form (available after March 1) or contact Merrill Cain at (313) 748-1842. -

50 Years of NASCAR Captures All That Has Made Bill France’S Dream Into a Firm, Big-Money Reality

< mill NASCAR OF NASCAR ■ TP'S FAST, ITS FURIOUS, IT'S SPINE- I tingling, jump-out-of-youn-seat action, a sport created by a fan for the fans, it’s all part of the American dream. Conceived in a hotel room in Daytona, Florida, in 1948, NASCAR is now America’s fastest-growing sport and is fast becoming one of America’s most-watched sports. As crowds flock to see state-of-the-art, 700-horsepower cars powering their way around high-banked ovals, outmaneuvering, outpacing and outthinking each other, NASCAR has passed the half-century mark. 50 Years of NASCAR captures all that has made Bill France’s dream into a firm, big-money reality. It traces the history and the development of the sport through the faces behind the scene who have made the sport such a success and the personalities behind the helmets—the stars that the crowds flock to see. There is also a comprehensive statistics section featuring the results of the Winston Cup series and the all-time leaders in NASCAR’S driving history plus a chronology capturing the highlights of the sport. Packed throughout with dramatic color illustrations, each page is an action-packed celebration of all that has made the sport what it is today. Whether you are a die-hard fan or just an armchair follower of the sport, 50 Years of NASCAR is a must-have addition to the bookshelf of anyone with an interest in the sport. $29.95 USA/ $44.95 CAN THIS IS A CARLTON BOOK ISBN 1 85868 874 4 Copyright © Carlton Books Limited 1998 Project Editor: Chris Hawkes First published 1998 Project Art Editor: Zoe Maggs Reprinted with corrections 1999, 2000 Picture Research: Catherine Costelloe 10 9876 5 4321 Production: Sarah Corteel Design: Graham Curd, Steve Wilson All rights reserved. -

Page 14 for the Answers to All of These Puzzles ORIGINAL VALLEY PENNYSAVER March 22, 2014 • A7

March 22, 2014 Volume 4 • Number 36 But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law. ~ Galatians 5:22-23 (From left, front) Christian Burke, Dawson Sweet, Elena Leduc, Raymond Mojica, Dina Daley, Zachary Herget, Emily Palmeri, Aliza Hopkins, (2nd row) Monaysia Garret, Megan Blakeslee, Brady Toher, Nevaeh Battisti, Holden Consorte and Mrs. Terranova, (back) volunteer Jake Pamkowski, Payton Drake, Gavin Freeman, Christian Meyers, Grace Nowalk and 2nd grade teacher Mrs. Emily Cheney celebrated NYS Agricultural Literacy Week at Canajoharie’s East Hill Elementary School. See more on page 22. Photo by Elizabeth A. Tomlin A2 • March 22, 2014 ORIGINAL VALLEY PENNYSAVER CHECK YOUR AD: Mrs. M. LLC ADVERTISERS should check their ads on the ADVERTISERS LANDSCAPING & SNOWPLOWING first week of insertion. Lee Publications, Inc. Get the best RESIDENTIAL OR COMMERCIAL shall not be liable for response from your typographical, or errors advertisements by in publication except to including the condi- the extent of the cost of tion, age, price and SNOW the first weeks inser- best calling hours. tion of the ad, and shall Also we always rec- also not be liable for ommend insertion for damages due to failure at least 2 times for PLOWING to publish an ad. maximum benefits. Adjustment for errors is Our deadline is limited to the cost of Thursday 12:00 Noon • Snow Plowing • Snow Removal that portion of the ad for the following wherein the error Saturday’s paper. • Snow Stacking • Snow Blowing occurred. Report any • De-Icing (Salt or Sand) • Shoveling errors to 518-673-3011 518-673-3011 LIKE us on Facebook! BOWS! 2014 Models www.facebook.com/theS are in!! New colors, portsmansDen Check for new styles, great Now Accepting New Customers tournament schedule. -

Speedway Motorsports, Inc. 2003 Annual Report Pewymtrprs N

2003 Major Corporate Partners Speedway Motorsports, Inc. 2003 Annual Report Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Opportunity At Every Turn 2003 Annual Report OPPORTUNITYAT EVERY TURN 704.455.3239 Speedway Motorsports, Inc. PO Box 600, Concord, NC 28026 • 5555 Concord Parkway South, Concord, NC 28027 www.gospeedway.com Board of Directors O. Bruton Smith Edwin R. Clark* James P. Holden** Chairman and Executive Vice President Retired President and Chief Executive Officer Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Chief Executive Officer Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Charlotte, NC DaimlerChrysler Charlotte, NC President and General Manager Bloomfield Hills, MI Atlanta Motor Speedway H.A. Wheeler Atlanta, GA Robert L. Rewey Chief Operating Officer Retired Group Vice President and President Marcus G. Smith** Ford Motor Company Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Executive Vice President Palm Beach, FL President and General Manager National Sales and Marketing Lowe’s Motor Speedway Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Tom E. Smith Concord, NC Concord, NC Retired Chairman Chief Executive Officer William R. Brooks William P. Benton and President BUSINESS DESCRIPTION Chief Financial Officer Retired Vice President of Food Lion Stores, Inc. Speedway Motorsports, Inc. (SMI) is a leading marketer and promoter of motorsports entertainment in Executive Vice President Marketing Worldwide Salisbury, NC the United States. SMI owns six speedways in growing markets across the country and has one of the and Treasurer Ford Motor Company largest total permanent seating capacities in the motorsports industry. Speedway Motorsports provides Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Palm Beach, FL **Board Member Emeritus upon the election of Marcus G. souvenir merchandising through SMI Properties, manufactures and distributes smaller-scale, modified Smith at the Annual Meeting on April 21, 2004. -

NASCAR Cup Series Champion to Receive Bill France Cup Beginning in 2020 NASCAR Honors Founding Family’S Legacy with New Championship Trophy

Contact: Pete Stuart NASCAR Communications 704.348.9621 [email protected] NASCAR Cup Series Champion to Receive Bill France Cup Beginning in 2020 NASCAR Honors Founding Family’s Legacy with New Championship Trophy DAYTONA BEACH, Fla. (February 14, 2020) – To honor the legacy of the sport’s founding family, NASCAR today announced that the Bill France Cup will be awarded to the champion of the NASCAR Cup Series, beginning in 2020. The renamed trophy pays tribute to Bill France Sr., who founded NASCAR in 1947, as well as his son, Bill France Jr., who elevated the sport to a national phenomenon as the sanctioning body’s chief executive from 1972 to 2003. “As the sport ushers in a new era, it’s fitting that my father’s name is associated with the highest mark of excellence in our sport,” said Jim France, NASCAR Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. “My father and brother’s vision for NASCAR has been realized, many times over, as millions of fans follow and engage each week with the best racing in the world.” The Bill France Cup, created by Jostens, will maintain the size and shape of last year’s championship trophy and will feature outlines of the 24 NASCAR Cup Series racetracks that comprise the 2020 season schedule. The trophy design will be updated as the race schedule evolves, and new tracks are introduced to NASCAR Cup Series competition. Bill France Sr. spearheaded NASCAR from its beginning and directed it to its current role as the world’s largest stock car racing organization. Born in Washington, D.C., on Sept. -

SRT Motorsports - Weekend Preview - June 7 New Track Surface, New Distance Adds Speed and Drama to Pocono Travis Pastrana, Dodge Dart in Texas for GRC Event

Contact: Matthew Simmons Adam Saal Bill Klingbeil SRT Motorsports - Weekend Preview - June 7 New Track Surface, New Distance Adds Speed and Drama to Pocono Travis Pastrana, Dodge Dart in Texas for GRC Event June 6, 2012, Auburn Hills, Mich. - Pocono Raceway welcomes the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series this weekend with a new racing surface and shorter race distance adding to the drama at one of the most historic and scenic tracks on the schedule. Pocono Raceway is certainly unique. Its three-turn design includes the longest frontstretch of any track in NASCAR, producing speeds in excess of 200 mph heading a relatively flat Turn 1. All three turns are different, causing headaches for crew chiefs and engineers who must find the right balance for their 3,500 lb. stock cars. Additionally, for the first time in the track’s history, the race is scheduled for 400 miles, down from 500. That adds a new wrinkle in fuel and pit strategy. Thirty-six NASCAR Sprint Cup Series drivers tested the freshly repaved track surface at Pocono on Wednesday in preparation for this weekend’s 400. Thirty-three of them eclipsed the best practice speed from last August’s event at the 2.5-mile facility. Testing at Pocono concludes today with a morning and afternoon session. “Engineers that like fast tracks are going to love Pocono,” said SRT Motorsports engineer Howard Comstock. “The complete repave of the facility since last summer is going to lead to incredible speeds on the two-and-a-half-mile, three-turn triangle. With the longest straightaways in Sprint Cup racing, Pocono has always been relatively fast.