Exploring Changes in NASCAR-Related Titles in the New York Times and the Johnson City Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Busch's Battle Ends in Glory

8 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Wednesday, December 09, 2015 QUESTIONS & ATTITUDE Compelling questions... and maybe a few actual answers What will I do for NASCAR news? It’s as close as we get to NASCAR hanging a “Gone fishing” sign on the door. Now what? After 36 races, a goodbye to Jeff Gordon and con- SPEED FREAKS gratulations to Kyle Busch, and with only about A couple questions Mission accomplished two months until the engines crank at Daytona, we had to ask — you need more right now? These days, this is the ourselves closest thing NASCAR has to a dark season. But there’ll be news. What sort of news? Danica Patrick’s NASCAR’s corner-office suits are huddling with newest Busch’s battle the boys in legal to find a feasible way to turn its race teams into something resembling fran- GODSPEAK: Third chises, which would break from the independent- crew chief in contractor system that served the purposes four years. Crew since the late-’40s. Well, it served NASCAR’s ends in glory purposes, along with owners and drivers who chief No. 1, Tony Gibson, took ran fast enough to escape creditors. But times Kurt Busch to the have changed; you’ll soon be reading a lot about men named Rob Kauffman and Brent Dewar and Chase this year. something called the Race Team Alliance. KEN’S CALL: It’s starting to take on Will it affect the race fans and the the feel of a dial- racing? a-date, isn’t it? Nope. So maybe you shouldn’t pay attention. -

NASCAR Sponsorship: Who Is the Real Winner? an Event Study Proposal

NASCAR Sponsorship: Who is the Real Winner? An event study proposal A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Meredith Seurkamp May 2006 Oxford, Ohio ii ABSTRACT NASCAR Sponsorship: Who is the Real Winner? An event study proposal by Meredith Seurkamp This paper investigates the costs and benefits of NASCAR sponsorship. Sports sponsorship is increasing in popularity as marketers attempt to build more personal relationships with their consumers. These sponsorships range from athlete endorsements to the sponsorship of an event or physical venue. These types of sponsorships have a number of costs and benefits, as reviewed in this paper, and the individual firm must use its discretion whether sports sponsorship coincides with its marketing goals. NASCAR, a sport that has experienced a recent boom in popularity, is one of the most lucrative sponsorship venues in professional sports. NASCAR, which began as a single race in 1936, now claims seventy-five million fans and over one hundred FORTUNE 500 companies as sponsors. NASCAR offers a wide variety of sponsorship opportunities, such as driver sponsorship, event sponsorship, track signage, and a number of other options. This paper investigates the fan base at which these marketing messages are directed. Research of NASCAR fans indicates that these fans are typically more brand loyal than the average consumer. NASCAR fans exhibit particular loyalty to NASCAR sponsors that financially support the auto racing sport. The paper further explains who composes the NASCAR fan base and how NASCAR looks to expand into additional markets. -

MOTORSPORTS a North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat

MOTORSPORTS A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat A REPORT PREPARED FOR NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS ASSOCIATION BY IN COOPERATION WITH FUNDED BY: RURAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTER, THE GOLDEN LEAF FOUNDATION AND NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS FOUNDATION October 2004 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remarks 6 Introduction 7 Methodology 8 Impact of Industry 9 History of Motorsports in North Carolina 10 Best Practices / Competitive Threats 14 Overview of Best Practices 15 Virginia Motorsports Initiative 16 South Carolina Initiative 18 Findings 20 Overview of Findings 21 Motorsports Cluster 23 NASCAR Realignment and Its Consequences 25 Events 25 Teams 27 Drivers 31 NASCAR Venues 31 NASCAR All-Star Race 32 Suppliers 32 Technology and Educational Institutions 35 A Strong Foothold in Motorsports Technology 35 Needed Enhancements in Technology Resources 37 North Carolina Motorsports Testing and Research Complex 38 The Sanford Holshouser Business Development Group and UNC Charlotte Urban Institute 2 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat Next Steps on Motorsports Task Force 40 Venues 41 Sanctioning Bodies/Events 43 Drag Racing 44 Museums 46 Television, Film and Radio Production 49 Marketing and Public Relations Firms 51 Philanthropic Activities 53 Local Travel and Tourism Professionals 55 Local Business Recruitment Professionals 57 Input From State Economic Development Officials 61 Recommendations - State Policies and Programs 63 Governor/Commerce Secretary 65 North -

Aug 2010.Pdf

July - August 2010 www.superbirdclub.com email: [email protected] Pete Hamilton Superbird Restoration Petty’s Garage in Level Cross North Carolina has unveiled their restoration of Pete Hamilton’s 1970 Daytona 500 winning Superbird race car. The car is owned by collector Todd Werner, who also owns a Petty 1971 Road Runner among quite a few other significant cars. At left in the group photo, you can see The King behind the car. Left of him is Dale Inman, and at the windshield pillar is Pete Hamilton crew chief, Richie Barsz. I am told that Richie was instrumental in visually identifying the car. Owner Todd Werner is second from left. There is not a lot of information about the history of the car that has been released publicly at this time. I am told that after 1970, the car was reportedly sold to privateer Doc Faustina , who entered it as a 1970 Road Runner in select Grand National races, s during 1971 and 1972. In later years, it was rebodied as a newer Charger and continued to race into the mid 1970’s. I hope to bring you more information about the car soon. At middle left, Richard is checking out the Maurice Petty built Hemi. You can see the car is still being lettered. Immediately after these photos were taken, the car was loaded up and headed for the Mopar Nationals in Columbus where it was on display in the Manufacturers Midway. Petty’s Garage is a specialty restoration facility operating from the former Petty Enterprises shops. 2010 Events Calendar page 2 September 9th-12th St Louis MO - Monster Mopar Weekend & Aero Car Display This event is coming up next month. -

I Welding Show Provides the Ultimate "Hands-On" Experience

^iBJiJjj] e Auto Inclu I focus on the No !JJjyUJJJ]JJJ]R PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN WELDING SOCIETY TO ADVANCE THE SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND APPLICATION OF WELDING AND ALLIED PROCESSES, INCLUDING JOINING, BRAZING, SOLDERING, CUTTING, AND THERMAL SPRAYING The Driving Force in LOtifte Welding tivi ..... .... i •l s N - ^^s^n^ s i "H'i i|l^ — Select-Arc Metal Cored Electrodes Select-Arc. Inc. offers a of rejects. These Select-Arc and trucks such as manifolds, in your specific automotive complete line of composite electrodes deliver smooth mufflers, catalytic converters industry welding application, metal cored, gas-shielded, arc transfer with negligible and tubing. call Select-Arc at 800-341-5215 stainless steel electrodes spatter and excellent bead or contact: Select-Arc also provides specially formulated to contour. They also bridge the 70C Series of premium increase welding productivity gaps and handle poor fit up metal cored, carbon steel SELECT in your demanding automo better than solid wire. This. electrodes which are ideal tive industry applications. coupled with superior for car and truck frames, feedability from our robotic The Select 400 Series of trailer and earth moving packaging, means greater electrodes (409C, 409C-Ti, equipment applications. PO. Box 259 409C-Cb and 439C-Ti) are productivity and cost Fort Loramie, OH 45845-0259 uniquely designed to maxi efficiency for you in the For more information on the Phone: (937) 295-5215 mize welding speeds while welding of exhaust system metal cored electrode best Fax: (937) 295-5217 minimizing the percentage components for automobiles suited to increase productivity www.select-arc.com Circle No. -

Fedex Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview

FedEx Racing Press Materials 2013 Corporate Overview FedEx Corp. (NYSE: FDX) provides customers and businesses worldwide with a broad portfolio of transportation, e-commerce and business services. With annual revenues of $43 billion, the company offers integrated business applications through operating companies competing collectively and managed collaboratively, under the respected FedEx brand. Consistently ranked among the world’s most admired and trusted employers, FedEx inspires its more than 300,000 team members to remain “absolutely, positively” focused on safety, the highest ethical and professional standards and the needs of their customers and communities. For more information, go to news.fedex.com 2 Table of Contents FedEx Racing Commitment to Community ..................................................... 4-5 Denny Hamlin - Driver, #11 FedEx Toyota Camry Biography ....................................................................... 6-8 Career Highlights ............................................................... 10-12 2012 Season Highlights ............................................................. 13 2012 Season Results ............................................................... 14 2011 Season Highlights ............................................................. 15 2011 Season Results ............................................................... 16 2010 Season Highlights. 17 2010 Season Results ............................................................... 18 2009 Season Highlights ........................................................... -

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

NASCAR for Dummies (ISBN

spine=.672” Sports/Motor Sports ™ Making Everything Easier! 3rd Edition Now updated! Your authoritative guide to NASCAR — 3rd Edition on and off the track Open the book and find: ® Want to have the supreme NASCAR experience? Whether • Top driver Mark Martin’s personal NASCAR you’re new to this exciting sport or a longtime fan, this insights into the sport insider’s guide covers everything you want to know in • The lowdown on each NASCAR detail — from the anatomy of a stock car to the strategies track used by top drivers in the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series. • Why drivers are true athletes NASCAR • What’s new with NASCAR? — get the latest on the new racing rules, teams, drivers, car designs, and safety requirements • Explanations of NASCAR lingo • A crash course in stock-car racing — meet the teams and • How to win a race (it’s more than sponsors, understand the different NASCAR series, and find out just driving fast!) how drivers get started in the racing business • What happens during a pit stop • Take a test drive — explore a stock car inside and out, learn the • How to fit in with a NASCAR crowd rules of the track, and work with the race team • Understand the driver’s world — get inside a driver’s head and • Ten can’t-miss races of the year ® see what happens before, during, and after a race • NASCAR statistics, race car • Keep track of NASCAR events — from the stands or the comfort numbers, and milestones of home, follow the sport and get the most out of each race Go to dummies.com® for more! Learn to: • Identify the teams, drivers, and cars • Follow all the latest rules and regulations • Understand the top driver skills and racing strategies • Have the ultimate fan experience, at home or at the track Mark Martin burst onto the NASCAR scene in 1981 $21.99 US / $25.99 CN / £14.99 UK after earning four American Speed Association championships, and has been winning races and ISBN 978-0-470-43068-2 setting records ever since. -

CHIEFLAND Thursday, May 9, 2019

Happy Mother's Day CHIEFLAND Thursday, May 9, 2019 Proudly servingITIZEN Chiefland and Levy County for 69 years C2 sections, 20 pages Volume 70, Number 9 www.chieflandcitizen.com Chiefland, FL 32644 $.75 Pillars in the community Chiefland Chamber of Commerce issues top annual awards at banquet SEAN ARNOLD/Citizen LEFT: Barbara Snow accepts the Citizen of the Year award from Chamber President Lewissa Mainwaring. RIGHT: Sheriff Bobby McCallum is first honoree for the new First Responder of the Year award. SEAN ARNOLD nity who is going above and beyond, It currently boasts around 35 employ- es its employees to be active in the Editor from school functions to community ees, including three logging crews, 10 community, and with that being said, events. truck drivers, three mechanics and Ken and Lynetta lead by example,” hree major honors were “(Snow) gives tirelessly to support four office employees. Lott said. the subject of the Greater bringing awareness, honor and mem- Lott detailed the Griners’ involve- Forester Eric Handley and Korey TChiefland Area Chamber of ory to our nation’s hero dogs to make ment in organizations inside and Griner accepted the award on behalf Commerce Awards Banquet on May a meaningful difference in the lives outside the industry, such as the of the company. 2, making this year’s edition a big of all hero dogs.” Log A Load For Kids program, which “Korey and I are the future of the draw. Hosted at Haven in Chiefland In addition to Snow’s volunteer helps provide care for children whose business and we’re just trying to con- with a slew of door prizes and an work for the U.S. -

Atlantic News

This Page © 2004 Connelly Communications, LLC, PO Box 592 Hampton, NH 03843- Contributed items and logos are © and ™ their respective owners Unauthorized reproduction 8 of this page or its contents for republication in whole or in part is strictly prohibited • For permission, call (603) 926-4557 • AN-Mark 9A-EVEN- Rev 12-16-2004 PAGE 8A | ATLANTIC NEWS | AUGUST 5, 2005 | VOL 31, NO 31 ATLANTICNEWS.COM . TOWN NEWS ROLL CALL ROUND UP HOUSE Rye selectmen discuss beach issues (A,B) MALPRACTICE PANEL SHOULD COUNT AT TRIAL — SB214 would set up panels consisting of a judge, a BY JESSICA JENKINS The signs have been posted should be removed when surfers has increased sub- doctor and a lawyer, to screen out malpractice cases. A unan- SPECIAL TO THE ATLANTIC NEWS only when lifeguards are on guards are not on duty but stantially this year and it is imous decision against a case could be used in a jury trial. duty. This practice has come will seek confirmation from difficult in some cases to RYE | Beach Commis- Supporters of the bill argue that this panel — if its recom- sioner Peter Clark addressed into question since the the town attorney. Clark keep surfers well separated mendations could be heard by a jury — is an effective way of Rye selectmen at a recent recent tragedy at Hampton indicated that the selectmen from swimmers. screening out frivolous cases, which would help bring down meeting to ask if the recently Beach. will receive a letter com- As mentioned at other the cost of malpractice insurance. Opponents thought that posted rip tide signs should The selectmen agreed plaining about surfers. -

1968 Hot Wheels

1968 - 2003 VEHICLE LIST 1968 Hot Wheels 6459 Power Pad 5850 Hy Gear 6205 Custom Cougar 6460 AMX/2 5851 Miles Ahead 6206 Custom Mustang 6461 Jeep (Grass Hopper) 5853 Red Catchup 6207 Custom T-Bird 6466 Cockney Cab 5854 Hot Rodney 6208 Custom Camaro 6467 Olds 442 1973 Hot Wheels 6209 Silhouette 6469 Fire Chief Cruiser 5880 Double Header 6210 Deora 6471 Evil Weevil 6004 Superfine Turbine 6211 Custom Barracuda 6472 Cord 6007 Sweet 16 6212 Custom Firebird 6499 Boss Hoss Silver Special 6962 Mercedes 280SL 6213 Custom Fleetside 6410 Mongoose Funny Car 6963 Police Cruiser 6214 Ford J-Car 1970 Heavyweights 6964 Red Baron 6215 Custom Corvette 6450 Tow Truck 6965 Prowler 6217 Beatnik Bandit 6451 Ambulance 6966 Paddy Wagon 6218 Custom El Dorado 6452 Cement Mixer 6967 Dune Daddy 6219 Hot Heap 6453 Dump Truck 6968 Alive '55 6220 Custom Volkswagen Cheetah 6454 Fire Engine 6969 Snake 1969 Hot Wheels 6455 Moving Van 6970 Mongoose 6216 Python 1970 Rrrumblers 6971 Street Snorter 6250 Classic '32 Ford Vicky 6010 Road Hog 6972 Porsche 917 6251 Classic '31 Ford Woody 6011 High Tailer 6973 Ferrari 213P 6252 Classic '57 Bird 6031 Mean Machine 6974 Sand Witch 6253 Classic '36 Ford Coupe 6032 Rip Snorter 6975 Double Vision 6254 Lolo GT 70 6048 3-Squealer 6976 Buzz Off 6255 Mclaren MGA 6049 Torque Chop 6977 Zploder 6256 Chapparral 2G 1971 Hot Wheels 6978 Mercedes C111 6257 Ford MK IV 5953 Snake II 6979 Hiway Robber 6258 Twinmill 5954 Mongoose II 6980 Ice T 6259 Turbofire 5951 Snake Rail Dragster 6981 Odd Job 6260 Torero 5952 Mongoose Rail Dragster 6982 Show-off -

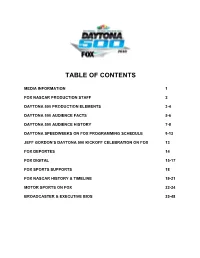

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb.