Regional Economic Impact of Texas Motor Speedway: a Simulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001

Video Name Track Track Location Date Year DVD # Classics #4001 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0001 Victory Circle #4012, WG 1951 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY D-0002 1959 Sports Car Grand Prix Weekend 1959 D-0003 A Gullwing at Twilight 1959 D-0004 At the IMRRC The Legacy of Briggs Cunningham Jr. 1959 D-0005 Legendary Bill Milliken talks about "Butterball" Nov 6,2004 1959 D-0006 50 Years of Formula 1 On-Board 1959 D-0007 WG: The Street Years Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1948 D-0008 25 Years at Speed: The Watkins Glen Story Watkins Glen Watkins Glen, NY 1972 D-0009 Saratoga Automobile Museum An Evening with Carroll Shelby D-0010 WG 50th Anniversary, Allard Reunion Watkins Glen, NY D-0011 Saturday Afternoon at IMRRC w/ Denise McCluggage Watkins Glen Watkins Glen October 1, 2005 2005 D-0012 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival Watkins Glen 2005 D-0013 1952 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen 1952 D-0014 1951-54 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1951-54 D-0015 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Weekend 1952 Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 1952 D-0016 Ralph E. Miller Collection Watkins Glen Grand Prix 1949 Watkins Glen 1949 D-0017 Saturday Aternoon at the IMRRC, Lost Race Circuits Watkins Glen Watkins Glen 2006 D-0018 2005 The Legends Speeak Formula One past present & future 2005 D-0019 2005 Concours d'Elegance 2005 D-0020 2005 Watkins Glen Grand Prix Festival, Smalleys Garage 2005 D-0021 2005 US Vintange Grand Prix of Watkins Glen Q&A w/ Vic Elford 2005 D-0022 IMRRC proudly recognizes James Scaptura Watkins Glen 2005 D-0023 Saturday -

2021 Nascar Cup Series

2021 NASCAR CUP SERIES DAY DATE TRACK LOCATION EVENT START TIME SUN 2/21 NCS Daytona Int’l Speedway Rd Course NCS at Daytona Road Course 2:00 PM SUN 2/28 NCS Homestead-Miami Speedway Dixie Vodka 400 2:30 PM SUN 3/7 NCS Las Vegas Motor Speedway Pennzoil 400 2:30PM SUN 3/14 NCS Phoenix Raceway NCS at Phoenix 2:30 PM SUN 3/21 NCS Atlanta Motor Speedway Folds of Honor QT 500 2:00PM SUN 3/28 NCS Bristol Motor Speedway-DIRT Food City 500 2:30PM SAT 4/10 NCS Blue Emu Max Pain Relief 500 Martinsville Speedway 7:30PM SUN 4/18 NCS Richmond Raceway Toyota Owners 400 2:00 PM SUN 4/25 NCS Talladega Superspeedway GEICO 500 1:00 PM SUN 5/2 NCS Kansas Speedway NCS at Kansas 2:00 PM SUN 5/9 NCS Darlington Raceway NCS at Darlington 2:30 PM SAT 5/15 INDY Indianapolis Motor Speedway Indy Motor Speedway Road Course 2:30PM SUN 5/16 NCS Dover Int’l Speedway Drydene 400 1:00 PM SUN 5/23 NCS Circuit of the Americas PRN TBD 1:30PM SUN 5/30 INDY Indianapolis Motor Speedway Indy 500 11:00AM SUN 5/30 NCS Charlotte Motor Speedway Coca-Cola 600 5:00PM SAT 6/6 NCS Sonoma Raceway Toyota/Save Mart 350 3:00PM SUN 6/13 NCS Texas Motor Speedway NASCAR All-Star Race 5:00 PM SUN 6/20 NCS Nashville Speedway NCS at Nashville 2:30 PM SAT 6/26 NCS Pocono Raceway NCS at Pocono-1 2:00 PM SUN 6/27 NCS Pocono Raceway NCS at Pocono-2 2:30 PM SUN 7/4 NCS Road America (WI) NCS at Road America 1:30 PM SUN 7/11 NCS Atlanta Motor Speedway Quaker State 400 2:30PM SUN 7/18 NCS New Hampshire Motor Speedway Foxwoods Resort Casino 301 2:00PM SUN 8/8 NCS Watkins Glen Int’l Go Bowling at the Glen -

2021 Credential Policy

2021 CREDENTIAL POLICY INDYCAR welcomes and appreciates at-track coverage from accredited members of the media. Media credentials for each NTT INDYCAR SERIES event are issued by that respective event’s track or promoter. Credential contacts for all 12 NTT INDYCAR SERIES venues are listed below as well as in the Tracks section of the 2021 NTT INDYCAR SERIES Media Guide. INDYCAR issues annual credentials (hard cards) to media covering a substantial number of races. Hard card media MUST contact the individual racetrack to request media center access, parking passes and any other special needs. Barber Motorsports Park Visit https://barberracingevents.com/ to request credentials. Only credentials submitted via the online request form will be considered. Credential Office Location: Hampton Inn, 310 Rex Lake Road, Birmingham, AL 35094 Streets of St. Petersburg Applications for media credentials are available on the MEDIA page at www.gpstpete.com. Credential Office Location: Rococo Steak, 655 2nd Ave S, St. Petersburg, FL 33701 Texas Motor Speedway No written or fax requests please; all credential requests are processed online at www.smicredentials.com; deadline is three weeks prior to the event. Credential Office Location: Trailer behind the ticket office/gift shop building near the lake on property. Indianapolis Motor Speedway Please send requests on company letterhead signed by the assigning editor to: IMS Media Credentials P.O. Box 24906 Indianapolis, IN 46224 Credential Office Location: Administration Building located at the corner of 16th & Georgetown Road. Raceway at Belle Isle Park Visit www.detroitgp.com to download media credential request form (available after March 1) or contact Merrill Cain at (313) 748-1842. -

Speedway Motorsports, Inc. 2003 Annual Report Pewymtrprs N

2003 Major Corporate Partners Speedway Motorsports, Inc. 2003 Annual Report Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Opportunity At Every Turn 2003 Annual Report OPPORTUNITYAT EVERY TURN 704.455.3239 Speedway Motorsports, Inc. PO Box 600, Concord, NC 28026 • 5555 Concord Parkway South, Concord, NC 28027 www.gospeedway.com Board of Directors O. Bruton Smith Edwin R. Clark* James P. Holden** Chairman and Executive Vice President Retired President and Chief Executive Officer Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Chief Executive Officer Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Charlotte, NC DaimlerChrysler Charlotte, NC President and General Manager Bloomfield Hills, MI Atlanta Motor Speedway H.A. Wheeler Atlanta, GA Robert L. Rewey Chief Operating Officer Retired Group Vice President and President Marcus G. Smith** Ford Motor Company Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Executive Vice President Palm Beach, FL President and General Manager National Sales and Marketing Lowe’s Motor Speedway Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Tom E. Smith Concord, NC Concord, NC Retired Chairman Chief Executive Officer William R. Brooks William P. Benton and President BUSINESS DESCRIPTION Chief Financial Officer Retired Vice President of Food Lion Stores, Inc. Speedway Motorsports, Inc. (SMI) is a leading marketer and promoter of motorsports entertainment in Executive Vice President Marketing Worldwide Salisbury, NC the United States. SMI owns six speedways in growing markets across the country and has one of the and Treasurer Ford Motor Company largest total permanent seating capacities in the motorsports industry. Speedway Motorsports provides Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Palm Beach, FL **Board Member Emeritus upon the election of Marcus G. souvenir merchandising through SMI Properties, manufactures and distributes smaller-scale, modified Smith at the Annual Meeting on April 21, 2004. -

SRT Motorsports - Weekend Preview - June 7 New Track Surface, New Distance Adds Speed and Drama to Pocono Travis Pastrana, Dodge Dart in Texas for GRC Event

Contact: Matthew Simmons Adam Saal Bill Klingbeil SRT Motorsports - Weekend Preview - June 7 New Track Surface, New Distance Adds Speed and Drama to Pocono Travis Pastrana, Dodge Dart in Texas for GRC Event June 6, 2012, Auburn Hills, Mich. - Pocono Raceway welcomes the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series this weekend with a new racing surface and shorter race distance adding to the drama at one of the most historic and scenic tracks on the schedule. Pocono Raceway is certainly unique. Its three-turn design includes the longest frontstretch of any track in NASCAR, producing speeds in excess of 200 mph heading a relatively flat Turn 1. All three turns are different, causing headaches for crew chiefs and engineers who must find the right balance for their 3,500 lb. stock cars. Additionally, for the first time in the track’s history, the race is scheduled for 400 miles, down from 500. That adds a new wrinkle in fuel and pit strategy. Thirty-six NASCAR Sprint Cup Series drivers tested the freshly repaved track surface at Pocono on Wednesday in preparation for this weekend’s 400. Thirty-three of them eclipsed the best practice speed from last August’s event at the 2.5-mile facility. Testing at Pocono concludes today with a morning and afternoon session. “Engineers that like fast tracks are going to love Pocono,” said SRT Motorsports engineer Howard Comstock. “The complete repave of the facility since last summer is going to lead to incredible speeds on the two-and-a-half-mile, three-turn triangle. With the longest straightaways in Sprint Cup racing, Pocono has always been relatively fast. -

Texas Motor Speedway: Print Advertising, Sponsorship

TEXAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY: PRINT ADVERTISING, SPONSORSHIP, LOGOS, AND CONGRUENCE by ELLEN STALLCUP Bachelor of Administration, 2003 Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of College of Communication Texas C hristian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science May, 2007 TEXAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY: PRINT ADVERTISING, SPONSORSHIP, LOGOS, AND CONGRUENCE Thesis approved: Major Professor For the College of Communication ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the support of family, friends, peers, colleagues, and professors, the goal of completing this degree could not have been achieved. First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Doug Newsom. Since arriving on campus, she was supportive of every thought and aspiration. She offered insight where I lacked vision and was a wonderful leader. I am continually inspired by her life and exp eriences. Thank you, Dr. Newsom, for your guidance and perpetual friendship. I would like to recognize Dr. Julie O’Neil , Dr. John Tisdale, and Dr. Robert Rhodes and thank them for providing continual direction and support as members of the committee . I am also deeply obliged to Dr. Stacy Grau who came on board as a member of the committee in the last hour. Her energy and willingness to help improve my research was remarkable. Additionally, thank you to those individuals who allowed me to conduct my research during their valuable class time. I will be forever indebted to those individuals of Texas Motor Speedway who continuously supported my every endeavor to achieve higher education. Kenton Nelson and Kevin Camper provided unyielding support from beginning to end. -

A Nascar Affiliated Marketing Company Was Looking for Someone That Could Custom Design and Build a Long Life Trailer. They Look

A Nascar affiliated marketing company was looking for someone that could custom design and build a long life trailer. They looked toward Featherlite, Optima and several other well known aluminum trailer manufactures and were just not impressed. We gave them a tour of ATC's factory and introduced them to a couple of our engineers and they knew that ATC was the manufacture that they were looking for. ATC's CAD prints helped them know exactly how the trailers would be laid out so that they could order the simulators and other equipment to have installed. Advantage was able to provide business financing that made purchasing these trailers easy. Keep your eyes open at the following tracks and you may get to see this trailer in person and do some racing! Atlanta Motor Speedway Charlotte Motor Speedway Autodromo Hermanos Rodriguez Mansfield Motorsports Speedway Bristol Motor Speedway Martinsville Speedway Auto Club Speedway Memphis Motorsports Park Chicagoland Speedway Michigan International Speedway Darlington Raceway The Milwaukee Mile Daytona International Speedway Nashville Superspeedway Dover International Speedway Nazareth Speedway Gateway Int'l Raceway New Hampshire Motor Speedway Homestead-Miami Speedway Phoenix International Raceway Indianapolis Motor Speedway Pikes Peak International Raceway Indianapolis Raceway Park Pocono Raceway Sonoma Raceway Richmond International Raceway Kansas Speedway Talladega Superspeedway Kentucky Speedway Texas Motor Speedway Las Vegas Motor Speedway Watkins Glen International. -

Ultimate Summer Showdown Will Bring the Heat from April to June

Ultimate Summer Showdown Will Bring the Heat from April to June April 22, 2021 BenQ Named as the Official Gaming Monitor of the Ultimate Summer Showdown Ultimate Summer Showdown Beginning April 23, 2021 and Concluding with the Finale on July 8, 2021 MIAMI, April 22, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Motorsport Games Inc. (NASDAQ: MSGM) (“Motorsport Games”), a leading racing game developer, publisher and esports ecosystem provider of official motorsport racing series throughout the world, today announced the Ultimate Summer Showdown. The four event esports series for NASCAR Heat 5 starts on April 30, 2021 and will culminate with a showpiece final on July 22, 2021. BenQ, a leading display technology company, has been named as the “Official Gaming Monitor Provider” for the Ultimate Summer Showdown. Open qualification for the Ultimate Summer Showdown begins online within NASCAR Heat 5 on April 30, 2021, with players on the PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system, the Xbox One NASCAR Heat 5 Logo family of devices including the Xbox One X and PC able to take part. The top 24 drivers from each platform will then be invited to take part in the live streamed event finals on Twitch, MOBIUZ YouTube and Facebook. The first race of the event will see players take to Darlington Raceway. “NASCAR Heat 5 has a strong, active community full of great racers and we cannot wait to give them another opportunity to showcase their talent on one of the biggest stages. The Ultimate Summer Showdown promises to build on the momentum of the recent Winter Heat Series,” commented Jay Pennell, General Manager, eNASCAR Heat Pro League, Motorsport Games. -

Certificate of Liability Insurance Xx/Xx/Xxxx This Certificate Is Issued As a Matter of Information Only and Confers No Rights Upon the Certificate Holder

DATE (MM/DD/YYYY) XX/XX/XXXX CERTIFICATE OF LIABILITY INSURANCE THIS CERTIFICATE IS ISSUED AS A MATTER OF INFORMATION ONLY AND CONFERS NO RIGHTS UPON THE CERTIFICATE HOLDER. THIS CERTIFICATE DOES NOT AFFIRMATIVELY OR NEGATIVELY AMEND, EXTEND OR ALTER THE COVERAGE AFFORDED BY THE POLICIES BELOW. THIS CERTIFICATE OF INSURANCE DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A CONTRACT BETWEEN THE ISSUING INSURER(S), AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE OR PRODUCER, AND THE CERTIFICATE HOLDER. IMPORTANT: If the certificate holder is an ADDITIONAL INSURED, the policy(ies) must be endorsed. If SUBROGATION IS WAIVED, subject to the terms and conditions of the policy, certain policies may require an endorsement. A statement on this certificate does not confer rights to the certificate holder in lieu of such endorsement(s). CONTACT PRODUCER NAME: PHONE FAX XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX (A/C, No, Ext): (A/C, No): E-MAIL ADDRESS: INSURER(S) AFFORDING COVERAGE NAIC # INSURER A : XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX INSURED INSURER B : INSURER C : XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX INSURER D : INSURER E : INSURER F : COVERAGES CERTIFICATE NUMBER: REVISION NUMBER: THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE POLICIES OF INSURANCE LISTED BELOW HAVE BEEN ISSUED TO THE INSURED NAMED ABOVE FOR THE POLICY PERIOD INDICATED. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY REQUIREMENT, TERM OR CONDITION OF ANY CONTRACT OR OTHER DOCUMENT WITH RESPECT TO WHICH THIS CERTIFICATE MAY BE ISSUED OR MAY PERTAIN, THE INSURANCE AFFORDED BY THE POLICIES DESCRIBED HEREIN IS SUBJECT TO ALL THE TERMS, EXCLUSIONS AND CONDITIONS OF SUCH POLICIES. LIMITS SHOWN MAY HAVE -

Sports Media, Inc Present NASCAR

Professional Sports Publications SOUVENIR PUBLICATIONS • NASCAR Official Race Programs provide fans with the drama, excitement and inside stories on America’s hottest and fastest growing sport. • There are 75 million NASCAR fans in the US; television ratings are second among sports only to the National Football League; average attendance at NASCAR’s premiere events top 190,000. • NASCAR is no longer a regional sport. Today, there is true national exposure. FOX and NBC televise 26 events (seven in prime time) and only half of the races are now held in the traditional south. • There is no better way to reach this loyal fan base than at the race through the Official Race Program. Each Race publication is available at the respective track for the corresponding Sprint Cup, Xfinity and Camping World race and allows the fans to take home a piece of their experience. • For the racing fan who thrills to 750-horsepower racing and rejoices in all the interests of the audience’s active, pedal-to-the-metal lifestyle, the program delivers everything they need. KEY BENEFITS Great Editorial The Only Game in Town The official program meets the needs With exclusive distribution rights of fans each and every race with both through the tracks, these programs national and local coverage. provide the fans with their only official source of insider information. These high-quality coffee table collectible programs provide fans High-Quality, Pre-Qualified with the hottest insider information Audience only an official magazine can deliver. • With both national and customized local team editorial, your advertising While editorial varies across the network message is delivered to a pre-qualified of official souvenir publications, key audience of interested fans in a positive, elements are typically included, such as: receptive environment. -

February 26 ...Daytona International Speedway March 05 ...Atlanta Motor Speedway March 12

FEBRUARY 26 . DAYTONA INTERNATIONAL SPEEDWAY AUGUST 19 . BRISTOL MOTOR SPEEDWAY Sunday• 1:00 PM . Daytona Beach FL Sunday • 6:30 PM . Bristol, TN MARCH 05 . ATLANTA MOTOR SPEEDWAY SEPTEMBER 03 . DARLINGTON RACEWAY Sunday• 1:30 PM . .Atlanta, GA Sunday • 5:00 PM . .Darlington, SC MARCH 12 . LAS VEGAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY SEPTEMBER 09 . RICHMOND INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY Sunday• 2:30 PM . .Las Vegas, NV Saturday • 6:30 PM . .Richmond, VA MARCH 19 . PHOENIX INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY Sunday• 2:30 PM . Avondale, AZ SEPTEMBER 17 . CHICAGOLAND SPEEDWAY MARCH 26 . AUTO CLUB SPEEDWAY Sunday •2:00 PM . Joliet, IL Sunday• 2:30 PM . Fontana, CA SEPTEMBER 24 . NEW HAMPSHIRE MOTOR SPEEDWAY APRIL 02 . MARTINSVILLE SPEEDWAY Sunday •1:00 PM . Loundon, NH Sunday• 1:00 PM . Ridgeway, VA OCTOBER 01 . .DOVER INTERNATIONAL SPEEDWAY APRIL 09 . TEXAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY Sunday •1:00 PM . Dover, PA Sunday• 12:30 PM . Fort Worth, TX OCTOBER 07 . .CHARLOTTE MOTOR SPEEDWAY APRIL 23 . BRISTOL MOTOR SPEEDWAY Saturday •6:00 PM . Concord, NC Sunday• 1:00 PM . .Bristol, TN OCTOBER 15 . .TALLADEGA SUPERSPEEDWAY APRIL 30 . .RICHMOND INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY Sunday •1:00 PM . Talladega, AL Sunday• 1:00 PM . .Richmond, VA OCTOBER 22 . KANSAS SPEEDWAY MAY 07 . TALLADEGA SUPERSPEEDWAY Sunday •2:00 PM . Kansas City, KS Sunday• 1:00 PM . Talladega, AL OCTOBER 29 . .MARTINSVILLE SPEEDWAY MAY 13 . KANSAS SPEEDWAY Sunday •12:00 Noon . Martinsville, VA Saturday• 6:30 PM . Kansas City, KS NOVEMBER 05 . .TEXAS MOTOR SPEEDWAY MAY 20 . CHARLOTTE MOTOR SPEEDWAY Sunday •1:00 PM . Fort Worth, TX Saturday• 5:00 PM . Concord, NC NOVEMBER 12 . PHOENIX INTERNATIONAL RACEWAY MAY 28 . -

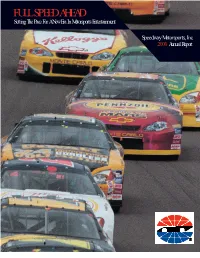

FULL SPEED AHEAD Setting the Pace for a New Era in Motorsports Entertainment

FULL SPEED AHEAD Setting The Pace For A New Era In Motorsports Entertainment Speedway Motorsports,Inc. 2000 Annual Report. “Under the new broadcast arrange- ments, we believe network and media exposure will increase expo- nentially, brightening the spotlight on our sport like never before.” –Bruton Smith TO OUR STOCKHOLDERS Innovation– the fuel that keeps Speedway Motorsports moving Our efforts to continually forward at lightning speed. Since our inception bolster interest in our sport more than 40 years ago, we have brought many included the construction of firsts to our sport, setting precedents the others short tracks at Lowe’s Motor follow. Never satisfied to stand still, innovation Speedway and Texas Motor continues to be our driving force. Speedway. Proving that everything old is new again, the new venues gave our Company the opportunity 2000 was a year in which we struggled against to return to our roots, and let fans experience the elements beyond our control. Lack of promotion by incomparable and unpredictable atmosphere of dirt broadcasters cooled overall media interest in the sport. track competition. The popularity of the tracks in We experienced one of the worst years in terms of Charlotte and Texas compelled us to offer a series weather. Also, the lack of an exciting Championship of dirt track races in Bristol, where new attendance point race in the Winston Cup Series further damp- records were set for two dirt ened ticket interest for the racing series. last six months of the year. A unique approach to fan It was also a year of transi- relations led to the forma- tion for our Company and the tion of the Fans First pro- entire industry as we entered gram.