Fender 1 Identifying the Art of Stage Management in Chicago Danny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loyola University Department of Theatre and Dance Course Syllabus Stagecraft II - Lecture

Loyola University Department of Theatre and Dance Course Syllabus Stagecraft II - Lecture COURSE INFORMATION INSTRUCTOR INFORMATION Course Title: THEA 104-001 / 002 - Stagecraft II – Lecture Instructor: Professor M.Aikens Course Time: MW 9:30 – 10:20 / 10:30-11:20 Office Location: Monroe 631 Required Lab: Stagecraft Lab II – THEA M106 (co-requisite) Office Hours: MW 11:30 – 12:30pm or by appt. Course Location: Monroe 630 – (or various by schedule) Office Phone: 504-865-2079 Email: mlaikens@loyno TEXTBOOK (Required) Stagecraft Fundamentals, 2nd Edition, Rita Kogler Carver ISBN-13: 978-0240820514 ISBN-10: 0240820517 (Recommended References) Theatrical Design & Production, J. Michael Gillette, 5th Ed., The Backstage Handbook, Paul Carter, 3rd Ed., COURSE FEE: $0 – LECTURE $100 - LAB REQUIRED MATERIALS: Mechanical pencil w/ extra lead *See Aikens re: best choices /coupons Metal ruler with non-slip or cork back 2” Binder – 3 ring / plastic cover on front and spine / inside pockets Tab dividers – 10 / writable / or printable tabs inserts Lamp kit – socket / harp / wiring / plug * A watercolor set with brushes * Colored pencils *See Aikens re: best choices /coupons * Sketch book – spiral bound / 100 sheets * Watercolor Paper --- each project may require additional materials per design choices REQUIRED SUPPLIES: Some supplies will be provided for you, however other supplies will be needed to complete projects and assignments. COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will combine lecture and laboratory work in its approach to the student learning the skills, tools, terminology and techniques required to create a theatrical production. Practical hands on exposure to the material covered in the lecture class will be offered during the Stagecraft Lab and department stage production process. -

Stage Manager & Assistant Stage Manager Handbook

SM & ASM HANDBOOK Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre STAGE MANAGER & ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER HANDBOOK December 12, 2008 Proposed changes and updates to the Producer Handbook can be submitted in writing or by email to the General Manager. The General Manager and Active Production Chair will enter all approved changes. VTG SM HANDBOOK: December 12, 2008 1 SM & ASM HANDBOOK Stage Manager & Assistant SM Handbook CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. AUDITIONS a) Pre-Audition b) Auditions and Callbacks c) Post Auditions / Pre First Rehearsal 3. REHEARSALS a) Read Through / First Rehearsal b) Subsequent Rehearsals c) Moving to the Mainstage 4. TECH WEEK AND WEEKEND 5. PERFORMANCES a) The Run b) Closing and Strike 6. SM TOOLS & TEMPLATES 1. Scene Breakdown Chart 2. Rehearsal Schedule 3. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Guidelines for Stage Management 4. The Prompt Book VTG SM HB: December 12, 2008 2 SM & ASM HANDBOOK 5. Production Technical Requirements 6. Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 7. Rehearsal Attendance Sheet 8. Stage Management Kit 9. Sample Blocking Notes 10. Rehearsal Report 11. Sample SM Production bulletins 12. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals on Mainstage – SM Guidelines 13. Rehearsals on the Mainstage – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 14. Sample Preset & Scene Change Schedule 15. Performance Attendance Sheet 16. Stage Crew Guidelines and Information Sheet 17. Sample Prompt Book Cues 18. Use of Theatre during Performances – SM Guidelines 19. Sample Production Information Sheet for FOH & Bar 20. Sample SM Preshow Checklist 21. Sample SM Intermission Checklist 22. SM Post Show Checklist 23. -

Stagecraft Syllabus

Mr. Craig Duke Theatre Production E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 908-464-4700 ext. 770 Syllabus 2010-2011 Period 2 Course Description: Theatre Production will introduce to the student, both novice and experienced, a practical approach to the technical and production aspects of musical theatre and drama. Students will learn the skills needed to construct scenery, hang and focus lighting instruments, implement a sound system for effects and reinforcement, and scenic artistry, all in a variety of techniques. In conjunction with the Music and Drama Departments, students will take an active role in each of the major productions at NPHS. Additionally, students will be introduced to theatrical design, and will be given an opportunity to draft their own designs for scenery and/or lighting of a theatrical production. Textbooks: There is no textbook for this class. Materials will be distributed in class, along with some notes. Several stagecraft books have been ordered for the NPHS Media Center. They are available in the reference section of the library, and I will refer to them in class from time to time. Most of the material presented comes from The Stagecraft Handbook by Daniel Ionazzi, and from Richard Pilbrow’s Stage Lighting Design. Course Topics: I. Introduction IV. Lighting for the Stage A. A Brief History of Theatre A. Why Light the Stage? B. The Production Team B. Instruments of the Designer C. Safety in the Theatre C. Properties of Light and Dark D. Tools of the Trade D. Color Theories II. Scenic Design for the Stage E. Lighting Design Paperwork A. -

Carnegie Mellon University 1

Carnegie Mellon University 1 School of Drama Peter Cooke, Head of School Office: Purnell Center for the Arts, 221 http://www.drama.cmu.edu Music Theater Option The students in the Music Theater program share the training philosophy The information contained in this section is accurate as of July 31, 2016 and much of the same curriculum as others in the acting option. In addition, and is subject to change. Please contact the School of Drama with any they take courses particular to the demands of Music Theater. These include questions. private voice along with training in a variety of dance techniques (Ballet, The School of Drama at Carnegie Mellon University is the oldest drama Jazz, Tap and Broadway Styles) and music theater styles and skills. program in the country. CMU Drama offers rigorous, world-class classical training in theater while providing thorough preparation for contemporary media. Design Option As a member of the Consortium of Conservatory Theater Training Programs, Design students are expected to develop artistic ability in the conception the school chooses students to participate in the program based on their and execution of scene, lighting, sound and costume design for plays of potential ability. Every Drama student is treated as a member of a theatrical all periods under varying theatrical conditions. Students may elect to have organization and must acquire experience in all phases of the dramatic a focus on one or two areas but must have a solid background in all four. arts. Students are also asked to broaden their knowledge through courses Freshmen in design receive instruction in drawing and painting, three- in the other colleges of the university. -

Be More Chill Broadway’S Digital Musical

www.lightingandsoundamerica.com April 2019 $10.00 Be More Chill Broadway’s Digital Musical ALSO: KISS: The Final Tour Ever Theatre on the Celebrity Edge What’s Up at Harman Professional? Introducing Preevue Inside the Milan Network Protocol Copyright Lighting &Sound America April 2019 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html THEATRE Copyright Lighting &Sound America April 2019 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html Ready Player ONe The Faust legend gets a software update—and a high-tech design—in Be More Chill By: David Barbour 50 • April 2019 • Lighting &Sound America The portals, modeled on smartphones, become illuminated to reveal what Boritt calls “gack:” TV monitors, lighting units, LED tape, and wiring. hese days, Broadway is loaded with musicals about teen Squip, who, invisible to others, appears to him as the angst and social anxiety, but Be More Chill , which opened manifestation of Keanu Reeves in The Matrix . He becomes in March at the Lyceum Theatre, gives these themes a dig - Jeremy’s strategic advisor and director of intelligence, ital (and science fiction) twist. In doing so, it aims to be faultlessly guiding him to popularity and working to Broadway’s first viral hit. Taken from the young adult novel maneuver him into the heart of Christine, the kooky drama t t i r by the late Ned Vizzini, Joe Tracz’s book focuses on club doyenne for whom he pines. Success comes at a o B f l Jeremy, a classic adolescent loser: His mom has bailed price: Jeremy, now convinced that life is a one-player u w o e and his depressed father can’t get out of his bathrobe, game, drops Michael for a new, thoroughly shallow, social B f o never mind the house. -

Theatreuni Stage Management Handbook

TheatreUNI Stage Management Handbook Contents Getting Started and Prep Week ................................................................................................................ 2 Rehearsals .................................................................................................................................................. 14 Before & After Rehearsals ....................................................................................................................... 22 Outside the Theatre ................................................................................................................................. 26 Tech ............................................................................................................................................................ 28 Performances ............................................................................................................................................ 40 Strike .......................................................................................................................................................... 42 Opera: The Other White Meat ................................................................................................................ 43 Appendix ................................................................................................................................................... 45 TheatreUNI Stage Management Handbook Getting Started and Prep Week Hierarchy As you get started on a production, it -

Stage Manager Expectations

The Department of Theatre University Theatre Stage Manager Duties & Responsibilities Listed below are the duties you perform and responsibilities you carry as stage manager. If the production does not have an Assistant Director, those tasks fall to the Stage Manager (see “Assistant Director Duties & Responsibilities”). For further instructions or clarification of anything you do not understand, see the TD (Technical Director). General Notes • Your attitude is crucial to the success of the production. The stage manager takes the initiative to solve any problems that may develop. A positive, constructive, and supportive attitude is essential. • The script for the production is available to you at the start of your assignment. You may pick up a script from the University Theatre Secretary in Room 317 Murphy. Remember that some scripts, especially for musicals, must be returned. Never mark in a script with anything but a pencil. • During your stage management period you are responsible for the security of the facility and equipment. You may pick up a set of Stage Manager keys from the Production Office (317 Murphy) as soon as the previous SM has turned them in. Be sure ALL doors are locked and equipment secured before you leave. You should be the first to arrive and the last to leave in all circumstances. If you are assigned to stage manage in the Inge Theatre and use the Crafton-Preyer Theatre stage as a crossover, be sure that the doors to the CPT and scene shop are locked before you leave unless there is an event going on in the CPT. -

THEATRE Technical Rider

Harriet & Charles Luckman Fine Arts Complex THEATRE Technical Rider Revised 3/19 Administrative Offices: (323) 343-6611 Theatre Operations: (323) 343-6630 3/5/19 Page 1 GENERAL INFORMATION Please Note: Equipment listed in this document is used throughout the Luckman Complex and is distributed on a first-come, first-served basis. Please confirm availability. Stage Dimensions † Loading Dock Dimensions† Proscenium Width 48’ (14.7M) Dock accommodates two trucks/trailers w/drivable Standard Masking Width 44’ (13.4M) ramp to Stage Level for smaller vehicles. Proscenium Height steps 28’ to 30’ Loading Dock Height 3’-8” (1.1M) Grid Height (Top of Steel) 78’-2” (23.8M) Loading Dock Width 20’-6” (6.2M) Center Line to SL Pinrail 55’-1” (16.8M) Loading Door 19’-4”h (5.9M) x 12’-1”w (3.7M) Center Line to SR Wall 57’-4” (17.5M) L shaped Assembly Area (interior) 2800 Sq Ft. Proscenium Line to Back wall 55’-6” (16.9M) SR Load Door 27’-10”h (8.5M) x 29’-9”w (9.1M) Proscenium Line to Apron* 1’-10” (.56M) Proscenium Line to DS Pit Lift Edge* 11’ (3.4M) Elevator to Basement 5’x2’x6’ high Orchestra Pit Size Raised 9’ x 36’ Dressing Rooms Orchestra Pit Size Lowered 13’ x 40’ (2) 1-2 Station Rooms (stage level) Orchestra Pit Travel Depth: (2) 3-4 Station Rooms (stage level) Stage Floor to Auditorium Floor 3’-1” (.94M) Women’s Chorus Room – 33 Stations (basement) Stage Floor to Pit Floor 10’-11” (3.3M) Men’s Chorus Room – 33 Stations (basement) Stage Floor to Storage Level 15’ (4.6M) Projection Booth to Proscenium Line 74’ (22.6M) Wardrobe Room includes: Washer, Dryer, Iron, Projection Booth to Screen Lineset 81’ (24.8M) Steamer, Ironing Board, Rolling Racks Balcony Rail to Proscenium line 61’-5” (18.7M) Support Spaces Lighting Throw, First AP* 46’ (13.9M) Large Rehearsal Hall 40’ x 52’ Lighting Throw, Second AP* 60’ (18.4M) Small Rehearsal Hall 32’ x 38’ The rehearsal halls have sprung floors, mirrors and Stage floor is sprung 2 levels of ballet barres half way around room. -

Stage Management Handbook (PDF)

Stage Management Handbook West Virginia University College of Creative Arts School of Theatre & Dance Revisions: If you would like to propose a revision to this handbook, please email the production manager. Outline the change you purpose and the reason for this proposal. Created By: Faculty & Staff of the School of Theatre & Dance 08/2012 Introduction Serving as a stage manager is an invaluable experience for a student at the School of Theatre & Dance. Not only are you part of a team to help develop a production, in the end you are the individual responsible for the production’s follow through. A good stage manager will practice the following traits: be proactive, assume responsibility, think ahead, be organized, and dependable. With each production your confidence and skills will grow, assisting you in your professional career after college. The stage manager is the first line of communication and serves as the hub that holds the different disciplines together. You must learn to communicate in a clear and timely manner and be able to express the ideas and vision of others. It is equally as important to treat everyone with respect, as you will need to form a professional working relationship with everyone involved in the production. It is crucial to develop a balance in life between your work, study, and play. Time management is one of the most important things a stage manager can learn. To achieve this will help you manage your day‐to‐day stress. Learn to leave your personal problems outside of the theatre, yet deal with the stresses of daily life quickly so it will not impact your work or study. -

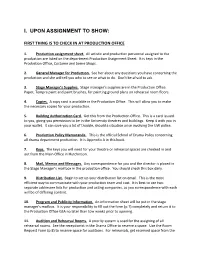

Stage Management Manual (PDF)

I. UPON ASSIGNMENT TO SHOW: FIRST THING IS TO CHECK IN AT PRODUCTION OFFICE 1. Production assignment sheet. All artistic and production personnel assigned to the production are listed on the department Production Assignment Sheet. It is kept in the Production Office, Costume and Scene Shops. 2. General Manager for Production. See her about any questions you have concerning the production and she will tell you who to see or what to do. Don’t be afraid to ask. 3. Stage Manager’s Supplies. Stage manager’s supplies are in the Production Office. Paper, Tempra paint and paint brushes, for painting ground plans on rehearsal room floors. 4. Copies. A copy card is available in the Production Office. This will allow you to make the necessary copies for your production. 5. Building Authorization Card. Get this from the Production Office. This is a card issued to you, giving you permission to be in the University theatres and buildings. Keep it with you in your wallet. It can save you a lot of trouble, should a situation arise involving the UW police. 6. Production Policy Memoranda. This is the official School of Drama Policy concerning all drama department production. It is Appendix A in this book. 7. Keys. The keys you will need for your theatre or rehearsal spaces are checked in and out from the Main Office in Hutchinson. 8. Mail, Memos and Messages. Any correspondence for you and the director is placed in the Stage Manager’s mail box in the production office. You should check this box daily. -

Stagecraft Syllabus 2018-19.Docx

Stagecraft (CTE) Syllabus Instructor: Ms. Kristina Cummins Room: Drama Email: [email protected] Phone: (360) 596-8043 Course Description: Stagecraft students will study theatre safety, set design and construction, lighting and audio for the theatre. Students are expected to obtain proficiency in using the systems in the Capital High School theatre. Other activities include theatre management, costume design and construction, and stage management in preparation for the upcoming CHS productions. VIDEO/PHOTOGRAPHY: In this course, we often video record students’ performances. Contact me directly if you wish for your child to NOT be photographed and video recorded. Textbook: Stagecraft Fundamentals: A Guide and Reference for Theatrical Production (Second Edition) Rita Kogler Carver Major Areas of Study: History and Art: Of Technical Theatre Scenic Design Basic Theatre Safety and Set Construction Theatrical Rigging and Lighting Sound Design Costume and Make-up Design Sound and Special Effects Stage Management and Careers Field Trip to Seattle Shakespeare to see Arms and the Man by George Bernard Shaw on Thursday, November 8, 2018 (permission due by September 28.) Materials / Supplies: Students need to bring the following to class daily Small 3- ring binder / folder Pencils, pens, highlighters, and notebook paper OPTIONAL: Safety Glasses, Work gloves, dust mask, and ear protection Students will be working with construction tools. It is essential that all safety rules are followed. We will have safety equipment on hand, but it is strongly recommended that students bring their own. Cummins 2018 – 2019 Leadership Points: In addition to the class work, students will need to contribute to CHS theatre outside of class time. -

Theatre Lingo

Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre THEATRE LINGO December 12, 2008 VTG Theatre Lingo: December 12, 2008 THEATRE LINGO acting areas a small area of the stage that has its own set of lights; lighting designers often divide the stage into acting areas in order to create balanced lighting. adlib to improvise lines or speeches that is not part of the script. amperage a measure of power flowing through cables, plugs and circuit breakers. amplifier an electronic device that makes an audio signal strong enough to create sound. anchor to secure a set piece to the stage floor. apron stage area in front of the proscenium. assistant stage manager (ASM) part of the stage management staff; is usually in charge of backstage crew. audition a performance reading before producers, directors, or others for the purpose of being cast in a production. auditory cue a cue that is called when a sound or musical note is heard; it often is executed by the sound board operator without being given a GO by the SM. back drop a large piece of canvas hung from a batten and painted to represent a particular scenic element. Also called a drop. back light light coming from upstage of an actor. backstage the area away from the acting area, including dressing rooms and the green room. Also called offstage. ballast an electronic device used by fluorescent and HMI lights; necessary to start up these kinds of lights. barn doors A colour frame with two or four flaps that cut off excess light.