BFI Future Film Member Joe Steen Recommends the Third Man (1949, Dir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intriguing Human Preference for a Ternary Patterned Reality

75 Kragujevac J. Sci. 27 (2005) 75-114. THE INTRIGUING HUMAN PREFERENCE FOR A TERNARY PATTERNED REALITY Lionello Pogliani,* Douglas J. Klein,‡ and Alexandru T. Balaban¥ *Dipartimento di Chimica Università della Calabria, 87030 Rende (CS), Italy; ‡Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, 77553-1675, USA; ¥ Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, 77551, USA E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; balabana @tamug.tamu.edu (Received February 10, 2005) Three paths through the high spring grass / One is the quicker / and I take it (Haikku by Yosa Buson, Spring wind on the river bank Kema) How did number theory degrade to numerology? How did numerology influence different aspects of human creation? How could some numbers assume such an extraordinary meaning? Why some numbers appear so often throughout the fabric of reality? Has reality really a preference for a ternary pattern? Present excursion through the ‘life’ and ‘deeds’ of this pattern and of its parent number in different fields of human culture try to offer an answer to some of these questions giving at the same time a glance of the strange preference of the human mind for a patterned reality based on number three, which, like the 'unary' and 'dualistic' patterned reality, but in a more emphatic way, ended up assuming an archetypical character in the intellectual sphere of humanity. Introduction Three is not only the sole number that is the sum of all the natural numbers less than itself, but it lies between arguably the two most important irrational and transcendental numbers of all mathematics, i.e., e < 3 < π. -

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

Spring 06 02-16.Indd

CENTER FOR AUSTRIAN STUDIES AUSTRIAN STUDIES NEWSLETTER Vol. 18, No. 1 Spring 2006 Reflections on William Fulbright’s legacy by Lonnie Johnson In April 2005, Fulbright commissions all over the world commemorated the centennial anniversary of the birth of J. William Fulbright (1905-1995), the founder of the US government’s flag- ship international educa- tional exchange program. As a junior senator from Arkan- sas, Fulbright endorsed a pro- active internationalist agenda during and after World War II and made a name for him- self not only as an advocate of the United Nations and educational exchange pro- grams, but also as one of the most courageous opponents of Joseph McCarthy. In August 1946, Fulbright was responsible for tagging an amendment on to the Sur- plus Property Act of 1944, which stipulated that for- U.S. Fulbright grantees visiting the Melk Monastery during their orientation program in September 2005. eign income earned overseas by the sale of US wartime property could be used to finance educational Salzburg, Klagenfurt, Linz, Graz, and Vienna, as well as collaborative exchange with other countries. This amendment laid the foundations for awards for students and scholars at the Diplomatic Academy, Internation- the educational exchange program that came to bear his name. The pro- ales Forschungszentrum Kulturwissenschaften (an international research gram is currently based on the Fulbright-Hayes Act of 1961, which pro- center for cultural studies), the Sigmund Freud Museum, and the Muse- vided US funding for the program as an annual line item in the federal umsQuartier in Vienna. The Fulbright Commission also cosponsors an budget and included provisions facilitating contributions to the program continued on page 25 by foreign governments and other entities. -

Midas' Servant, Ceyx, Morpheus As Ceyx, Orpheus, Apollo, A, Philemon

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Playing the Third Man (Midas' Servant, Ceyx, Morpheus as Ceyx, Orpheus, Apollo, A, Philemon) in Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses: a production thesis Ronald Ludlow Reeder Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reeder, Ronald Ludlow, "Playing the Third Man (Midas' Servant, Ceyx, Morpheus as Ceyx, Orpheus, Apollo, A, Philemon) in Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses: a production thesis" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3653 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PLAYING THE THIRD MAN (MIDAS’ SERVANT, CEYX, MORPHEUS AS CEYX, ORPHEUS, APOLLO, A, PHILEMON) IN MARY ZIMMERMAN’S METAMORPHOSES: A PRODUCTION THESIS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural And Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In The Department of Theatre By Ronald Ludlow Reeder B.F.A., University of Texas at Austin, 1991 B.S., University of Texas at Austin, 1994 May, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………...………………iii -

The Third Man"

"THE THIRD MAN" by Graham Greene HIGH ANGLE - FULL SHOT - CITY OF VIENNA The title VIENNA SUPERIMPOSED FADES OUT - commentary commences. COMMENTATOR I never knew the old Vienna before the war, with its - MED. SHOT - STATUE OF A VIOLINIST There is snow on it. COMMENTATOR Strauss music, its glamour and easy charm... MED. SHOT - ROW OF STONE STATUES ornamenting the top of a building. In the b.g. the top of a stone archway. They are snow-sprinkled. COMMENTATOR Constantinople suited... MED. SHOT - SNOW-COVERED STATUE Trees in b.g. COMMENTATOR me better. I really got to know it in the... CLOSE SHOT - TWO MEN talking in the street. COMMENTATOR - classic period of the black... CLOSEUP - SUITCASE opens toward camera, revealing contents consisting of tins of food, shoes, etc. The hands of a man come in from f.g. to take something out. COMMENTATOR - market. We'd run anything... CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE standing side by side in the street. The person CL running hands through a pair of silk stockings. COMMENTATOR - if people wanted it enough. CLOSEUP - HANDS OF TWO PEOPLE A woman's hands CL wearing a wedding ring - a man's hands CR holding in RH two small cartons - hands them over to her in exchange for some notes which she hands him. COMMENTATOR - and had the money to pay. CLOSE SHOT - FIVE WRIST WATCHES on a man's wrist from which the coat sleeve is turned back. COMMENTATOR Of course a situation like that - LONG SHOT - CAPSIZED SHIP in shallow water with a drowned body floating on the water CR of it. -

Mnozil Brass Study Guide

TUESDAY MARCH 24 2020 10 AM CIRQUE MNOZIL BRASS 2019-2020 FIELD TRIP SERIES BROADEN THE HORIZONS OF YOUR CLASSROOM. EXPERIENCE THE VIBRANT WORLD OF THE ARTS AT THE McCALLUM! EXPANDING THE CONCEPT OF LITERACY What is a “text”? We invite you to consider the performances on McCallum’s Field Trip Series as non-print texts available for study and investigation by your students. Anyone who has shown a filmed version of a play in their classroom, used a website as companion to a textbook, or asked students to do online research already knows that LEARNING LINKS “texts” don’t begin and end with textbooks, novels, and reading packets. They extend to videos, websites, games, plays, concerts, dances, radio programs, and a number of other non-print texts that students and teachers engage with on a regular basis. We know that when we expand our definition of texts to the variety of media that we use in our everyday lives, we broaden the materials and concepts we have at our disposal in the classroom, increase student engagement, and enrich learning experiences. Please consider how utilizing your McCallum performance as a text might align to standards established for reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language. How do we help students to use these texts as a way of shaping ideas and understanding the world? Please use this material to help you on this journey. NON-PRINT TEXT > any medium/text that creates meaning through sound or images or both, such as symbols, words, songs, speeches, pictures, and illustrations not in traditional print form including those seen on computers, films, and in the environment. -

Click to Download

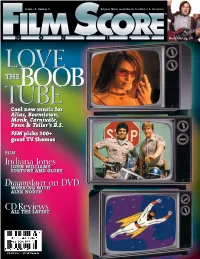

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

The Third Man 2004

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Drew Bassett Rob White: The Third Man 2004 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bassett, Drew: Rob White: The Third Man. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 21 (2004), Nr. 2, S. 250– 251. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2004.2.1856. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. Fotogrqfie 1111d Film Roh White: The Third Man London: BFI Publishing 2003 (BFI Film Classics). -

THE THIRD MAN Involved in an Opium-Smuggling Operation

CD 7A: “Every Frame Has a Silver Lining” - 10/26/1951 Passing through Iran, Harry becomes THE THIRD MAN involved in an opium-smuggling operation. Lives of Harry Lime CD 7B: “Mexican Hat Trick” - 11/02/1951 Program Guide by Elizabeth McLeod Down on his luck in Mexico, opportunity Orson Welles in The Third Man beckons Harry…thanks to a pickpocket! It’s a hard job being a middle-aged wunderkind, especially in show business -- where you’re only as good as your last big success. And CD 8A: “Art Is Long and Lime Is Fleeting” - 11/09/1951 as Orson Welles moved into his mid-thirties, the triumphs of his youth The painting Harry’s trying to sell isn’t really a Renoir, but does that seemed increasingly remote. The Mercury Theatre was just a memory, really matter? and so was the bold 1930s experimental theatre scene that gave it life. Postwar America, with its increasing restrictions on intellectual freedom CD 8B: “In Pursuit of a Ghost” - 11/16/1951 and its suspicion of anyone who dared to color outside the lines, had Harry is caught up in a rush of events and finds himself in the middle of little use for a superannuated boy wonder…especially one who’d made a banana-republic revolution! a career of antagonizing the Establishment. Orson Welles may have been a genius, but it didn’t take a genius to know that there wasn’t much call anymore for the kind of work that he did so well. He’d burned his Elizabeth McLeod is a journalist, author, and broadcast bridges in Hollywood -- and the radio networks, seeing the approaching historian. -

The Ampleforth Journal

The Ampleforth Journal September 2017 - December 2018 Volume 122 4 THE AMPLEFORTH JOURNAL VOL 122 ConTenTS eDiToriAl 6 The Abbey The Ampleforth Community 7 on the holy Father’s Call to holiness in Today’s World 10 Volunteering for the Mountains of the Moon 17 everest May 2018 25 Time is running out 35 What is the life of a Christian in a large corporation? 40 The british officer and the benedictine Tradition 45 A Chronicle of the McCann Family 52 The Silent Sentence 55 Joseph Pike: A happy Catholic Artist 57 Fr Theodore young oSb 62 Fr Francis Dobson oSb 70 Fr Francis Davidson oSb 76 Abbot Timothy Wright oSb 79 Prior Timothy horner oSb 85 Maire Channer 89 olD AMPleForDiAnS The Ampleforth Society 90 old Amplefordian obituaries 93 AMPleForTh College headmaster’s exhibition Speech 127 into the Woods 131 ST MArTin’S AMPleForTh Prizegiving Speech 133 The School 140 CONTENTS 5 eDiToriAl Fr riChArD FFielD oSb eDiTor oF The AMPleForTh JournAl The recent publicity surrounding the publishing of the iiCSA report in August may have awakened unwelcome memories among those who have suffered at the hands of some of our brethren. We still want to reach out to them and the means for this are still on the Ampleforth Abbey website under the safeguarding tab. it has been encouraging to us to receive so many messages of support and to know that no parents saw fit to remove their children from our schools. And there is increasing interest from all sorts of people in the retreats run here throughout the year by different monks, together with requests for monks to go and speak or preach at different venues and events. -

The Museum of Modern Art Celebrates Vienna's Rich

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART CELEBRATES VIENNA’S RICH CINEMATIC HISTORY WITH MAJOR COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema Is Held in Conjunction with Carnegie Hall’s Citywide Festival Vienna: City of Dreams, and Features Guest Appearances by VALIE EXPORT and Jem Cohen Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema February 27–April 20, 2014 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 29, 2014—In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, The Museum of Modern Art presents a major collaborative exhibition exploring Vienna as a city both real and mythic throughout the history of cinema. With additional contributions from the Filmarchiv Austria, the exhibition focuses on Austrian and German Jewish émigrés—including Max Ophuls, Erich von Stroheim, and Billy Wilder—as they look back on the city they left behind, as well as an international array of contemporary filmmakers and artists, such as Jem Cohen, VALIE EXPORT, Michael Haneke, Kurt Kren, Stanley Kubrick, Richard Linklater, Nicholas Roeg, and Ulrich Seidl, whose visions of Vienna reveal the powerful hold the city continues to exert over our collective unconscious. Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema is organized by Alexander Horwath, Director, Austrian Film Museum, Vienna, and Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, MoMA, with special thanks to the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. The exhibition is also held in conjunction with Vienna: City of Dreams, a citywide festival organized by Carnegie Hall. Spanning the late 19th to the early 21st centuries, from historical and romanticized images of the Austro-Hungarian empire to noir-tinged Cold War narratives, and from a breeding ground of anti- Semitism and European Fascism to a present-day center of artistic experimentation and socioeconomic stability, the exhibition features some 70 films. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES with ALPINE ZITHER MUSIC Gertrud Maria Huber University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna

MÜZİK VE KİMLİK GÜZ 2015 / SAYI 12 “EXCUSE ME, I’D LIKE ANOTHER VELTLINER, PLEASE!“1 - PERFORMED IDENTITIES WITH ALPINE ZITHER MUSIC Gertrud Maria Huber University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna Abstract The Alpine zither has a special status and signifi cance among the music instruments as very ‘German’ or ‘Alpine’. This young stringed musical instrument, which has emerged in its present form and style of playing in the last two centuries, is still today mainly present in the amateur music and zither club scene. The plucked zither was originally used in Alpine folk music. With common symbols individuals share common identity, musicians are identifi ed by the instrument and the music they play. What is stereotypical about the image of the Alpine zither and do zither players see their instrument symbolic in the same way? How does zither music differ inside the common group? In my paper I would like to use this instrument as a focus for understanding the processes of social change, the dealing with inclusion and exclusion and the shifting in concepts of identity among the Alpine zither players. Little about the zither has been published. Most books have been written by amateur researchers. In addition, the Zither music has hardly been the focus of researchers. Because relevant research fi ndings are so scarce, emphasis rests on those ethnomusicological methods involving audio-visual recorded fi eld research. The Alpine zither is often simply referred to as the typical musical instrument of cultural importance within the German speaking Alpine area. What is stereotypical about this image? Do zither players see their instrument symbolic in the same way? Quite naturally and not thinking much about it I recently packed the zither in the instrument case and slipped into my Alpine Dirndl costume, when I left for a Musikantenstammtisch 2 in a Viennese Heuriger3 wine tavern in Hernals.