Russian Peasant Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spirit of Discovery

Foundation «Интеркультура» AFS RUSSIA 2019 THE SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY This handbook belongs to ______________________ From ________________________ Contents Welcome letter ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 3 1. General information about Russia ………………………………………………………………… Page 4 - Geography and Climate ……………………………………………………………………………… Page 4 - History ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 5 - Religion ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 6 - Language ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 6 2. AFS Russia ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 7 3. Your life in Russia …………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 11 - Arrival ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 11 - Your host family ……………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 12 - Your host school …………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 13 - Language course …………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 15 - AFS activities ……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 17 * Check yourself, part 1 ………………………………………………………………………………………. Page 18 4. Life in Russia …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 20 - General information about Russian Families ………………………………… Page 20 - General information about the School system……………………………… Page 22 - Extracurricular activities …………………………………………………………………………………… Page 24 - Social life …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Page 25 - Holidays and parties ……………………………………………………………………………………. Page 28 5. Russian peculiarities ………………………………………………………………………………………….. Page 29 6. Organizational matters ……………………………………………………………………………………… -

Politics, Feasts, Festivals SZEGEDI VALLÁSI NÉPRAJZI KÖNYVTÁR BIBLIOTHECA RELIGIONIS POPULARIS SZEGEDIENSIS 36

POLITICS, FEASTS, FESTIVALS SZEGEDI VALLÁSI NÉPRAJZI KÖNYVTÁR BIBLIOTHECA RELIGIONIS POPULARIS SZEGEDIENSIS 36. SZERKESZTI/REDIGIT: BARNA, GÁBOR MTA-SZTE RESEARCH GROUP FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS CULTURE A VALLÁSI KULTÚRAKUTATÁS KÖNYVEI 4. YEARBOOK OF THE SIEF WORKING GROUP ON THE RITUAL YEAR 9. MTA-SZTEMTA-SZTE VALLÁSIRESEARCH GROUP KULTÚRAKUTATÓ FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS CSOPORT CULTURE POLITICS, FEASTS, FESTIVALS YEARBOOK OF THE SIEF WORKING GROUP ON THE RITUAL YEAR Edited by Gábor BARNA and István POVEDÁK Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology Szeged, 2014 Published with the support of the Hungarian National Research Fund (OTKA) Grant Nk 81502 in co-operation with the MTA-SZTE Research Group for the Study of Religious Culture. Cover: Painting by István Demeter All the language proofreading were made by Cozette Griffin-Kremer, Nancy Cassel McEntire and David Stanley ISBN 978-963-306-254-8 ISSN 1419-1288 (Szegedi Vallási Néprajzi Könyvtár) ISSN 2064-4825 (A Vallási Kultúrakutatás Könyvei ) ISSN 2228-1347 (Yearbook of the SIEF Working Group on the Ritual Year) © The Authors © The Editors All rights reserved Printed in Hungary Innovariant Nyomdaipari Kft., Algyő General manager: György Drágán www.innovariant.hu https://www.facebook.com/Innovariant CONTENTS Foreword .......................................................................................................................... 7 POLITICS AND THE REMEMBraNCE OF THE Past Emily Lyle Modifications to the Festival Calendar in 1600 and 1605 during the Reign of James VI and -

The State of the Spruce Stands of the Boreal and Boreal Subboreal

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10(2), 16-22, doi: 10. 15421/2020_57 RESEARCH ARTICLE The State of the Spruce Stands of the Boreal and Boreal- Subboreal Forests of the Eastern European Plain in the Territory of the Udmurt Republic (Russia) 1* 2 1 3 1 I. L. Bukharina , A. Konopkova , K. E. Vedernikov , O. A. Svetlakova , A. S. Pashkova 1FSBEI HE Udmurt State University, Professor, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Russian Federation, Izhevsk, Udmurt Republic 2Technical University Zvolen, Slovak Republic, Zvolen 3FSBEI HE Izhevsk State Agricultural Academy, Russian Federation, Izhevsk, Udmurt Republic Corresponding author E-mail: bukharina. usu@inbox. ru Received: 09.03.2020. Accepted 09.04.2020 This article presents materials evaluating the dynamics of spruce stands in the zone of coniferous-deciduous forests and the southern taiga zone of the European part of the Russian Federation in the territory of the Udmurt Republic. The analysis of the State Forest Register for the Udmurt Republic showed that the largest reduction in the area of spruce stands was observed in the southern part of the republic. The descriptions of the test areas established in various forestry zones revealed that the spruce stands were characterized by a low density of trees, whereby the absolute completeness of the studied stands varied from 2. 95 to 11. 1 m2/ha. A high content of deadwood was noted, which in volume exceeded the stock of raw-growing forest. The analysis of forest litter on the trial plots showed that most of them were completely decomposed residues or litter, ranging from 44% to 77%; a prevalence of the upper undecomposed layer over the semi-decomposed middle layer was noted. -

Udmurtia. Horizons of Cooperation.Pdf

UDMURTIA Horizons of Cooperation The whole world is familiar fiber, 8th – in production of pork; or hammer out a nail for a house with the gun maker Mikhail Ka- it is among 5 major regions - fur- with your own hands to have a tra- lashnikov, motor cycles «Izh», the niture producers in Russia and ditional Udmurt wedding, to re- composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky and among 10 major regions of Russia cover physical health with help of the skier Galina Kulakova but as producing dairy and meat prod- unique mud, mineral waters and long as 20 years ago there were ucts. health-giving honey (apiotherapy) few people who were able to as- Acquaintance with future part- and spiritual health – in cathe- sociate them with Udmurtia. Now ners from Udmurtia is related to drals and at sacred springs, to re- it is just a fact in history explained business tourism. Citizens of oth- lieve stresses of the metropolitan by strategic significance of the er countries and regions of Russia city in the patriarchal tranquility Republic in the defense complex when selecting a holiday destina- of villages, to choose an educa- of Russia and its remoteness from tion will not consider our region tional institution for studying. the state borders. as a health resort or touristic cen- Udmurtia is the region of hospi- Business partner highly appre- ter along with London or Paris in table and purposeful people open ciate products manufactured in the first place. for dialogue and cooperation. the Republic and extend relations However, Udmurtia is attrac- with its manufacturers. tive not only as the industrial-in- Udmurtia produces equipment novative or educational center. -

Booklet Elecond.Pdf

ОАО "Элеконд" является одним из основных производителей и поставщиков на российский рынок и в страны СНГ алюминиевых, ниобиевых и танталовых конденсаторов. Предприятие находится в городе Сарапуле Удмуртской республики, в одном из промышленно развитых районов Западного Урала, Имеет удобное транспортное сообщение. Через г. Сарапул проходит Горьковская железная дорога, есть речной порт. Город связан сетью автомобильных дорог с соседними областными центрами, республиками, аэропортом города Ижевска, Open Joint-Stock Company «ELECOND», a leading Russian manufacturer of aluminum, tantalum and niobium capacitors, supplies its products to RF and CIS markets. The company is situated in Sarapul, Udmurt Republic - an industrially developed region of Western Ural. Sarapul has favorable transport communications: it has a railway station (Gorky railway) and a river port and is connected to neighboring regional centers, republics and airport of Izhevsk via roads, Удмуртская Республика расположена в западной части Среднего Урала между реками Кама и Вятка. На западе и севере она граничит с Кировской областью, на востоке - с Пермской областью, на юге - с Башкортостаном и Татарстаном. Территория Удмуртии занимает площадь 42,1 тыс.кв.км. Столица - город Ижевск. Наиболее древние археологические памятники свидетельствуют о том, что люди на территории Удмуртии появились в эпоху мезолита (8-5 тыс. лет до н.э.). Первые русские поселения появились на р. Вятке в XII-XIII веках. Север Удмуртии стал частью формирующегося Русского государства. К 1557 году после взятия Иваном Грозным Казани завершился процесс присоединения удмуртов к Русскому государству. До Октябрьской революции территория Удмуртии входила в состав Казанской и Вятской губерний. Благодаря своему выгодному геополитическому положению Удмуртия в XX веке превратилась в крупный промышленный центр страны. \VS Сегодня Удмуртская Республика является неотъемлемой составной частью Российской Федерации. -

A Necktie for Lawyer Shumkov

A Necktie for Lawyer Shumkov By Vladimir Voronov Translated by Arch Tait January 2016 This article is published in English by The Henry Jackson Society by arrangement with Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. The article refects the views of the author and not necessarily those of The Henry Jackson Socity or its staf. A NECKTIE FOR LAWYER SHUMKOV 1 On the evening of Friday, 4 December 2015 the body of 43-yeAr old Dmitry Shumkov wAs discovered in an office in the Federation Tower of the Moscow City business centre. Shumkov’s name became known to the general public only from reports of his deAth. These reports, summArizing the dynamic business life of the deceAsed, reveAled that Mr Shumkov wAs A dollAr billionaire; co-owner of the Olympic Sports Complex in Moscow; co-owner of the Norilsk-1 mines; co-owner of A complex of buildings AdjAcent to the Kremlin on VArvarka Street And Kitai- Gorod Drive; owner of a “Centre for Network Impact Technology”, which is one of the top five Internet traffic regulators; And, owner of A mAjority holding in the Moscow Internet eXchange” (MSK-IX) hub, which serves 60% of Russian Internet trAffic, And of NGENIX, the mArket leAder in services providing content. The successes of the deceAsed were not confined to business. He wAs one of the top ten Russian lawyers, A Doctor of Laws, Professor of Public Administration And Legal Support of State And Municipal Services of the Russian Presidential AcAdemy of NAtionAl Economy and Public Service, Academic Director of the Institute of Energy Law At the Kutafin Moscow State Law University, A member of the Presidium of the Russian Law Society And ChairmAn of the BoArd of the Russian NAtionAl Centre for Legal InitiAtives. -

Classification of Urban Habitats of Towns of the Udmurt Republic (Russia)

Plants in Urban Areas and Landscape Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering DOI 10.15414/2014.9788055212623.105–107 CLASSIFICATION OF URBAN HABITATS OF TOWNS OF THE UDMURT REPUBLIC (RUSSIA) Ekaterina N. ZYANKINA, Olga G. BARANOVA* Udmurt State University, Russia The purpose of this study is to discover the species composition of urban floras through studying and comparing certain partial floras. The object of our research is flora of small towns in Udmurtia. We have developed methodological approaches for analysis of different urban habitats. These approaches are significant for identifying of plants species composition in cities. This study is based on the method of partial floras. The term “partial flora” is understood in the interpretation of Boris A. Yurtsev. This method is widely used in Russia (Yurtsev, 1982). We’ve created the classification of habitats groups based on examination of cartographic material, aerial and satellite photography, primary analysis of the flora habitats. We have distinguished two types, 16 classes and 43 habitats kinds. The Type of natural and semi-natural habitats with little disturbance of vegetation is divided into 7 classes of habitats: meadow, forest, forest-steppe, swamp, water, coastal, naturally bare habitats. The type of anthropogenically – transformed habitats includes 9 classes: communicationly-tape, erosion, slotted, agricultural, water, artificial tree plantation, landfills, landscape gardenings, cemeteries Preliminary lists of kinds of partial flora habitats are made. Both native and alien species of plants are allocated there. Alien flora fraction was divided into groups according to the degree of danger for biodiversity. Typical species were pointed out for all habitats. -

Agrarian Technologies in Russia in the Late XIX - Early XX Centuries: Traditions and Innovations (Basing on the Materials of Vyatka Province)

ISSN 0798 1015 HOME Revista ESPACIOS ! ÍNDICES ! A LOS AUTORES ! Vol. 38 (Nº 52) Year 2017. Page 32 Agrarian technologies in Russia in the late XIX - early XX centuries: traditions and innovations (basing on the materials of Vyatka province) Tecnologías agrarias en Rusia a finales del siglo XIX-principios del XX: tradiciones e innovaciones (basándose en los materiales de la provincia de Vyatka) Alexey IVANOV 1; Anany IVANOV 2; Alexey OSHAYEV 3; Anatoly SOLOVIEV 4; Aleksander FILONOV 5 Received: 09/10/2017 • Approved: 21/10/2017 Content 1. Introduction 2. Methodology 3. Results 4. Conclusions Bibliographic references ABSTRACT: RESUMEN: Basing on a wide range of published and unpublished Basándose en una amplia gama de fuentes publicadas e sources the article examines the historical experience of inéditas, el artículo examina la experiencia histórica de introducing and disseminating new technologies of la introducción y difusión de nuevas tecnologías de agricultural production in the peasant economy of producción agrícola en la economía campesina de la Vyatka province in the late 19th and early 20th provincia de Vyatka a fines del siglo XIX y principios del centuries when the most important changes took place XX, cuando se produjeron los cambios más importantes in the agriculture of Russia. The most notable en la agricultura de Rusia. El fenómeno más notable phenomenon for the agricultural province was the para la provincia agrícola fue la introducción de una introduction of a multi-field (grass-field) crop rotation in rotación de cultivos -

IZHEVSK ELECTROMECHANICAL PLANT) ━━ Two-Component Solutions for Peritoneal Dialysis

INVESTMENT AUDIT OF THE UDMURT REPUBLIC. VERSION 1.0 UDMURTIA ON THE MAP OF RUSSIA 1 Moscow MADE IN UDMURTIA Kirov 42,100 SQ KM Perm Nizhny Novgorod Area Izhevsk (56th/85*) Kazan Yekaterinburg Ufa Samara 1.5M Population (30th/85*) UDMURTIA’S LARGEST CITIES RUB 556BN 970 КМ GRP IZHEVSK 650,000 Distance from Izhevsk (33rd/85*) to Moscow: SARAPUL 98,000 2 hours VOTKINSK 98,000 18 hours — 1200 km GLAZOV 93,000 RUB 356,043 GRP per capita (42nd/85) KEY TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE: Trans-Siberian Railway (Balezino Station, Glazov Station) The P320 Elabuga-Izhevsk regional highway, connection to M7 Volga. Udmurt Republic * ranking among Russian regions Volga Federal District (VFD) IGOR SHUVALOV MAKSIM ORESHKIN DENIS MANTUROV DMITRY PATRUSHEV 3 Chairman of VEB.RF Minister of Economic Development Minister of Industry and Trade Minister of Agriculture THE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION HAS INITIATED AN INVESTMENT AUDIT TO SUPPORT UDMURTIA’S LONG-TERM ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT MADE IN UDMURTIA 2014 2017 2019 2020 “VEB.RF, the Russian Export “Udmurtia’s focus on driving non- “Udmurtia is a region with “Udmurtia’s climate and Centre, DOM.RF and the SME resource-based exports, training enormous investment potential environment provide an excellent Investment strategy Map of investment Investment audit Udmurt Republic’s 2027 opportunities Social and Economic Corporation are providing people entrepreneurs and promoting and ambitious goals to develop foundation for the further Udmurtia’s 2025 The investment audit of Strategy of Udmurtia with essential support entrepreneurship, enhancing the manufacturing sector. There development of the agribusiness, Investment Strategy In 2017, Udmurtia the Udmurt Republic will tools to attract investors, open productivity and adopting best is intense demand for investment food, raw materials and consumer is aimed at enhancing undertook a massive highlight the following: The strategy will be based on new manufacturing sites, create practices from other regions, among companies in Udmurtia goods sectors. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Paul Kulikovsky №89 August 2015 A procession in memory of Tsarevich Alexei was made for the twelfth time A two-day procession in honor of the birth of the last heir to the Russian throne - St. Tsarevich Alexei, was made for the twelfth time on August 11-12 from Tsarskoye Selo to Peterhof. The tradition of the procession was born in 2004 - says the coordinator of the procession Vladimir Znahur - The icon painter Igor Kalugin gave the church an icon of St. Tsarevich. We decided that this icon should visit the Lower dacha, where the Tsarevich was born. We learned that in "Peterhof" in 1994 was a festival dedicated to the last heir to the imperial throne. We decided to go in procession from the place where they lived in the winter - from Tsarskoye Selo. Procession begins with Divine Liturgy at the Tsar's Feodorovsky Cathedral and then prayer at the beginning of the procession. The cross procession makes stops at churches and other significant sites. We called the route of our procession "From Sadness to Joy." They lived in the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo, loved it, there was born the Grand Duchess Olga. But this palace became a prison for the last of the Romanovs, where they then went on their way of the cross. It was in this palace the Tsarevich celebrated his last birthday", - says Vladimir. The next morning, after the Liturgy, we go to the birthplace of the Tsarevich - "Peterhof". Part of the procession was led by the clergy of the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul in Peterhof, Archpriest Mikhail Teryushov and Vladimir Chornobay. -

I–V Century Middle Kama Tarasovo Burial Ground – a Unique Monument of Ancient Udmurts

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2017, 21, 2, 186–215 https://doi.org/10.3176/arch.2017.2.05 Rimma Goldina I–V CENTURY MIDDLE KAMA TARASOVO BURIAL GROUND – A UNIQUE MONUMENT OF ANCIENT UDMURTS The Tarasovo burial ground (Russia, Udmurtia) is the largest among researched Finno- Ugric monuments of the I–V c. in Eurasia. It was excavated in 1980–1997 by the Kama- Vyatka archaeological expedition of the Udmurt State University (Izhevsk) under the guidance of Professor R. D. Goldina. 1,880 graves containing 2,096 burials and over 37,000 artifects were excavated on the area of more than 16,000 sq. m. The cemetery is dated to the end of the Early Iron Age and the Great Migration period (in the Middle Kama Region – the Cheganda archaeological culture of the Pyanoborye culture-historical community – ancient Udmurts). The monument is located on the territory of the IV–III c. BC sanctuary the remains of which were also studied. Materials of the monument are under study of the group of archaeologists at the Udmurt State University. The paper gives a brief review of the following studies: burial ritual, chronological account of the materials from the I to V centuries, numerous categories of goods such as metal decorations, belt set, fibulas, earthenware, weapons: bladed weapons, helmets, armour, heads of spears and arrows, fighting scythes, axes, scabbard, horse tack, etc. Rimma Goldina, Department of History, Archaeology and Ethnology of Udmurtia of the Institute of History and Sociology at the Udmurt State University, 1 Universitetskaya St., 426034 Izhevsk, Russia; [email protected] Introduction At present, the Tarasovo burial ground is the largest among all known and researched Finno-Ugric burial monuments in Eurasia. -

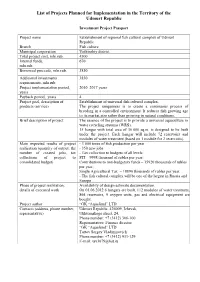

List of Projects Planned for Implementation in the Territory of the Udmurt Republic

List of Projects Planned for Implementation in the Territory of the Udmurt Republic Investment Project Passport Project name Establishment of regional fish cultural complex of Udmurt Republic Branch Fish culture Municipal corporation Votkinskiy district Total project cost, mln.rub. 4500 Internal funds, 670 mln.rub. Borrowed proceeds, mln.rub. 3830 Additional investments 3830 requirements, mln.rub. Project implementation period, 2010–2017 years years Payback period, years 4 Project goal, description of Establishment of universal fish cultural complex. products (service) The project uniqueness is to create a continuous process of breeding in a controlled environment. It reduces fish growing age to its market size rather than growing in natural conditions. Brief description of project The essence of the project is to provide a universal aquaculture in water recycling systems (WRS). 15 hangar with total area of 36 000 sq.m. is designed to be built under the project. Each hangar will include 72 reservoirs and modules of water treatment (based on 1 module for 2 reservoirs). Main expected results of project - 3 000 tones of fish production per year realization (quantity of output, the - 350 new jobs number of created jobs, tax - Tax collection to budgets of all levels: collections of project to PIT – 9998 thousand of rubles per year; consolidated budget) Contributions to non-budgetary funds – 15920 thousands of rubles per year; Single Agricultural Tax – 18890 thousands of rubles per year. - The fish cultural complex will be one of the largest in Russia and Europe Phase of project realization, Availability of design estimate documentation. details of executed work On 01.06.2012 6 hangars are built, 112 modules of water treatment, 864 reservoirs, 9 oxygen units, gas and electrical equipment are bought.