Importance of Pocket Estuaries in Skagit Bay May 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island County Whatcom County Skagit County Snohomish County

F ir C re ek Lake Samish k Governors Point e re C k es e n e Lawrence Point O r Ba r y Reed Lake C s t e n Fragrance Lake r a i C n Whiskey Rock r n e F a m e r W h a t c o m r W k i Eliza Island d B a y Cain Lake C r e B e Squires Lake t y k k n e North Pea u y pod o n t C u e Doe Bay C o Carter Poin a t r e Doe Bay C r r e C e k r e v South Peapod l Doe Island i S Sinclair Island Urban Towhead Island Vendovi Island Rosario Strait ek Cre Deer Point ll ha Eagle Cliff ite Pelican Beach h W k e Colony Creek e Samish Bay r Obstruction Pass ler C But D Blanchard r y P C a r H r e Clark Point a k s r e r e o William Point i k s k e n Tide Point o e r n e r C C C s r e e Cyp Jack Island d e ress Island l Cypress Lake i k Colony W C ree k Fish Point Blakely Island Samish Island Indian Village Cypress Head Scotts Point Strawberry Island Deepwater Bay n Slough Strawberry Island Guemes Island Padilla Bay Edison SloEudgihso Edison Swede C r Cypress Island e ek Blakely Island Guemes Island Black Rock Cypress Island Reef Point Guemes Island Armitage Island Huckleber ry SIsaladnddlebag Island Dot Island Southeast Point reek Guemes s C a Kellys Point m o h T Fauntleroy Point Hat Island W ish Ri i ll Sam ver ard Creek Cap Sante Decatur Hea Jamdes Island k Shannon Point Anacortes Cree Cannery Lake rd ya ck ri Sunset Beach B Green P oint Jo White Cliff e Le ar y Belle Rock Slo Fidalgo Head Crandall Spit ugh Anaco Beach Weaverling Spit Bay View March Point Burrows Island Fidalgo Young Island Alexander Beach Heart Lake Allan Island Whitmarsh Junction Rosario -

Anacortes Museum Research Files

Last Revision: 10/02/2019 1 Anacortes Museum Research Files Key to Research Categories Category . Codes* Agriculture Ag Animals (See Fn Fauna) Arts, Crafts, Music (Monuments, Murals, Paintings, ACM Needlework, etc.) Artifacts/Archeology (Historic Things) Ar Boats (See Transportation - Boats TB) Boat Building (See Business/Industry-Boat Building BIB) Buildings: Historic (Businesses, Institutions, Properties, etc.) BH Buildings: Historic Homes BHH Buildings: Post 1950 (Recommend adding to BHH) BPH Buildings: 1950-Present BP Buildings: Structures (Bridges, Highways, etc.) BS Buildings, Structures: Skagit Valley BSV Businesses Industry (Fidalgo and Guemes Island Area) Anacortes area, general BI Boat building/repair BIB Canneries/codfish curing, seafood processors BIC Fishing industry, fishing BIF Logging industry BIL Mills BIM Businesses Industry (Skagit Valley) BIS Calendars Cl Census/Population/Demographics Cn Communication Cm Documents (Records, notes, files, forms, papers, lists) Dc Education Ed Engines En Entertainment (See: Ev Events, SR Sports, Recreation) Environment Env Events Ev Exhibits (Events, Displays: Anacortes Museum) Ex Fauna Fn Amphibians FnA Birds FnB Crustaceans FnC Echinoderms FnE Fish (Scaled) FnF Insects, Arachnids, Worms FnI Mammals FnM Mollusks FnMlk Various FnV Flora Fl INTERIM VERSION - PENDING COMPLETION OF PN, PS, AND PFG SUBJECT FILE REVIEW Last Revision: 10/02/2019 2 Category . Codes* Genealogy Gn Geology/Paleontology Glg Government/Public services Gv Health Hl Home Making Hm Legal (Decisions/Laws/Lawsuits) Lgl -

Marine Shoreline Protection Assessment for Skagit County

Marine Shoreline Protection Assessment for Skagit County Shoreline property on Samish Island with Skagit Land Trust Conservation Easement. SLT files. Prepared for and with funding from: Skagit County Marine Resources Committee Prepared by: Kari Odden, Skagit Land Trust This project has been funded wholly or in part by the United States Environmental Protection Agency. The contents of this document do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Table of Contents Tables, Figures and Maps…………………………………………………………………………………..3 Introduction and Background…………………………………………………………………………….4 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Results……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………24 Tidelands Analysis…………………………………………………………………………………………….25 Data limitations………………………………………………………………………………………………..31 References…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…32 Appendix A: Protection Assessment Data Index……………………………………………..………..33 Appendix B: Priority Reach Metrics…………………………………………………………..……………..38 Marine Shoreline Protection Assessment for Skagit Co Page 2 Tables Table 1: Samish Bay Management Unit Priority Reaches………………………………………..……...13 Table 2: Padilla Bay Management Unit Priority Reaches……………………………………………..….15 Table 3: Swinomish Management Unit Priority Reaches……………………………………………..….17 Table 4: Islands Management Unit Priority Reaches…………………………………………………….…19 -

Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area Whatcom County, WA Wings Over

Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area Blaine Middle Whatcom County, WA School / PAC l, ul G ant, G rmor Wings Over Water 2020 C o n Nest s ero Birch Bay Field Trip Eagles! H March 21, 2020 Eagle "Trees" Beach Erosion Dakota Creek Eagle Nest , ics l at w G rr rfo la cial E te Ab a u ant W Eagle Nest n d California Heron Rookery Creek Wave Cut Terraces Kingfisher G Nests Roger's Slough, Log Jam Birch Bay Eagle Nest G Beach Erosion Sea Links Ponds Periglacial G Field Trip Stops G Features Birch Bay Route Birch Bay Berm Ice Thickness, 2,200 M G Surficial Geology Alluvium Beach deposits Owl Nest Glacial outwash, Fraser-age in Barn k Glaciomarine drift, Fraser-age e e Marine glacial outwash, Fraser-age r Heron Center ll C re Peat deposits G Ter Artificial fill Terrell Marsh Water T G err Trailhead ell M a r k sh Terrell Cr ee 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 ± Miles 2200 M Blaine Middle Glacial outwash, School / PAC Geology of Blaine-Birch Bay Area marine, Everson ll, G Gu Glaciomarine Interstade Whatcom County, WA morant, C or t s drift, Everson ron Nes Wings Over Water 2020 Semiahmoo He Interstade Resort G Blaine Semiahmoo Field Trip March 21, 2020 Eagle "Trees" Semiahmoo Park G Glaciomarine drift, Everson Beach Erosion Interstade Dakota Creek Eagle Nest Glac ial Abun E da rra s, Blaine nt ti c l W ow Eagle Nest a terf California Creek Heron Glacial outwash, Rookery Glaciomarine drift, G Field Trip Stops marine, Everson Everson Interstade Semiahmoo Route Interstade Ice Thickness, 2,200 M Kingfisher Surficial GNeeoslotsgy Wave Cut Alluvium Glacial Terraces Beach deposits outwash, Roger's Glacial outwash, Fraser-age Slough, SuGmlaacsio mSataridnee drift, Fraser-age Log Jam Marine glacial outwash, Fraser-age Peat deposits Beach Eagle Nest Artificial fill deposits Water Beach Erosion 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 Miles ± Chronology of Puget Sound Glacial Events Sources: Vashon Glaciation Animation; Ralph Haugerud; Milepost Thirty-One, Washington State Dept. -

Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits

PNNL-17161 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Development of a Hydrodynamic Model of Puget Sound and Northwest Straits Z Yang TP Khangaonkar December 2007 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062; ph: (865) 576-8401 fax: (865) 576-5728 email: [email protected] Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, VA 22161 ph: (800) 553-6847 fax: (703) 605-6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm This document was printed on recycled paper. -

Skagit SMP Public Comments Includes All Comments from Public Comment Period (April 22 – June 22, 2021) Including the May 11, 2021 Public Hearing

Skagit SMP Public Comments Includes all comments from Public Comment Period (April 22 – June 22, 2021) including the May 11, 2021 Public Hearing Index of All Textual Comments (#1-87) Comment Submitted Name Organization 21 05/14/2021 Rick Anderson Number On 22 5/19/2021 Dale Malmberg 1 04/22/2021 Julia Gates 23 05/22/2021 GARY HAGLAND Citizens Alliance for Property 2 04/25/2021 Albert Lindstrom Rights, Skagit Chapter 3 04/25/2021 Ronald Haworth 24 05/31/2021 Donna Mason 4 04/25/2021 Lisa Lewis 25 05/31/2021 Joe Geivett Emerald Bay Equity 5 04/26/2021 John Stewart 26 6/11/2021 DENNIS KATTE Lake Cavanaugh Improvement 6 04/27/2021 Glen Johnson Association 27 6/13/2021 Larita Humble Lake Cavanaugh Improvement 7 04/28/21 Peter H. Grimlund Association 8 04/28/2021 David Lynch 28 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring Evergreen Islands, Washington 9 04/29/2021 Tammy Force 29 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring Environmental Council, RE Sources, and Guemes Island 05/02/2021 William Daniel 10 30 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring Planning Advisory Committee 11 05/04/2021 Mark Johnson 31 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 12 05/04/2021 George Sidhu 32 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 13 05/06/2021 john martin 33 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 14 05/07/2021 DENNIS KATTE Lake Cavanaugh Improvement 34 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring Association 35 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 15 05/08/2021 Rich Wagner 36 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 16 05/10/2021 DENNIS KATTE Lake Cavanaugh Improvement Association 37 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 17 05/10/2021 Sandy Wolff 38 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring 18 05/13/2021 Rein Attemann Washington Environmental 39 6/16/2021 Kyle Loring -

Bookletchart™ Anacortes to Skagit Bay NOAA Chart 18427

BookletChart™ Anacortes to Skagit Bay NOAA Chart 18427 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the it at all stages of the tide. The pass is also used by log tows from the N bound to Everett or Seattle, which prefer this route to avoid the rough National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration weather W of Whidbey Island. National Ocean Service Currents in the narrows of Deception Pass attain velocities in excess of Office of Coast Survey 8 knots at times and cause strong eddies along the shores. With W weather, heavy swells and tide rips form and make passage dangerous www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov to all small craft. (See the Tidal Current Tables for daily predictions.) 888-990-NOAA Canoe Pass, N of Pass Island, is not recommended except for small craft with local knowledge. What are Nautical Charts? Deception Island, 1 mile W of Pass Island, is 0.4 mile NW of West Point, the NW end of Whidbey Island. A shoal which bares at low water Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show extends 175 yards (160 meters) S of Deception Island. Foul ground water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much extends 262 yards (240 meters) NW of West Point. The passage more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and between these two hazards is 200 yards (183 meters) wide with a least efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial depth of 2.5 fathoms and great care should be taken when navigating in ships that carry America’s commerce. -

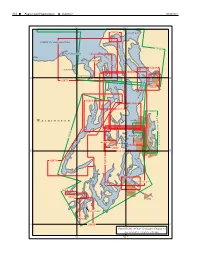

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

Sediment Transport Into the Swinomish Navigation Channel, Puget Sound—Habitat Restoration Versus Navigation Maintenance Needs

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Sediment Transport into the Swinomish Navigation Channel, Puget Sound—Habitat Restoration versus Navigation Maintenance Needs Tarang Khangaonkar 1,*, Adi Nugraha 1, Steve Hinton 2, David Michalsen 3 and Scott Brown 3 1 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] 2 Skagit River System Cooperative, La Conner, WA 98257, USA; [email protected] 3 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, P.O. Box 3755, Seattle, WA 98124, USA; [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (S.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-528-3053 Academic Editor: Zeki Demirbilek Received: 26 February 2017; Accepted: 12 April 2017; Published: 21 April 2017 Abstract: The 11 mile (1.6 km) Swinomish Federal Navigation Channel provides a safe and short passage to fishing and recreational craft in and out of Northern Puget Sound by connecting Skagit and Padilla Bays, US State abbrev., USA. A network of dikes and jetties were constructed through the Swinomish corridor between 1893 and 1936 to improve navigation functionality. Over the years, these river training dikes and jetties designed to minimize sedimentation in the channel have deteriorated, resulting in reduced protection of the channel. The need to repair or modify dikes/jetties for channel maintenance, however, may conflict with salmon habitat restoration goals aimed at improving access, connectivity and brackish water habitat. Several restoration projects have been proposed in the Skagit delta involving breaching, lowering, or removal of dikes. To assess relative merits of the available alternatives, a hydrodynamic model of the Skagit River estuary was developed using the Finite Volume Community Ocean Model (FVCOM). -

Stratification on the Skagit Bay Tidal Flats by Vera L

Stratification on the Skagit Bay Tidal Flats by Vera L. Pavel B.S., California Institute of Technology, 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the AASSACHUSETTS INST ffE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 0"T 2 2 2012 and the WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION September 2012 © 2012 Vera Pavel. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT and WHOI permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. J, Signature of Author Joint Program in Applied Ocean Science and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution June 26, 2011 Certified by Britt Raubenheimer Associate Scientist, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution =" Thesis supervisor Approved by David E. Hardt Chairman, Department of Mechanical Engineering Committee oqGr iduib Theses Massaggus l iof -Technology Approved by - -enrik Schmidt Chairman, Joint Committee for Applied Ocean ce and Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology/ Woods Hole ceanographic Institution 2 Stratification on the Skagit Bay tidal flats by Vera Pavel Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT and the Joint Committee for Applied Ocean Science and Engineering at MIT and WHOI on June 26, 2012 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanographic Engineering. Abstract Estuarine density stratification may be controlled primarily by cross-shore processes (analogous to longitudinal control in narrow estuaries), or by both cross- and alongshore processes (typical of coastal plumes). Here field observations and numerical modeling are used to investigate stratification on the low-sloped, periodically inundated Skagit Bay tidal flats. -

Draft Whidbey Basin Characterization Page 1 June 16, 2008

Preliminary Draft Whidbey Basin Characterization June 16, 2008 Instructions for Reviewers: Developing a characterization of a region as large and diverse as the Whidbey Basin is not an easy task, and one that cannot be done in a vacuum. Input from the people who live and work in this Basin, who study and deal with these issues often on a daily basis, is vital to making this a meaningful document. The document before you is a beginning framework with some of the pieces filled in. It is very much a preliminary draft and there are many gaps. Your engagement and contributions are needed to help identify and fill those gaps, and refine the information presented. As you read and critique this document please try to answer the following questions: 1) What information and associated documents are missing? If possible, please provide the information and source. 2) Is the information provided accurate to the best of your knowledge? Can you provide documented information to clarify? 3) Do you see this process as a useful effort? If not, how could it be improved? During the development process, there will be two opportunities to provide written comments and one opportunity to meet and discuss this paper with your peers. • June 20th Initial written comments due to [email protected]. These comments will contribute to the work session discussion. • June 24th Technical work session at Padilla Bay, 9-4. • RSVP to [email protected] • Come prepared to discuss at least one topic area in detail. • Bring questions you would like answered and insights you would like to share. -

South Fork Skagit Restoration Monitoring to Develop and Test Restoration Design Tools

South Fork Skagit Restoration Monitoring to Develop and Test Restoration Design Tools Nearshore Database Project Number: 07-1107 Proponent Contact Info: Steve Hinton Skagit River System Cooperative Director of Restoration [email protected] (360) 466-7243 Site Access Contact Info: W. Gregory Hood Skagit River System Cooperative Senior Restoration Ecologist [email protected] (360) 466-7282 Site Location: South Fork Skagit River Delta, including Deepwater Slough restoration site Milltown Island restoration site Wiley Slough restoration site Fisher Slough restoration site Reference tidal marshes All sites are located on the Skagit River, downstream from Conway, WA. Latitude 48.315˚ Longitude -122.365˚ Start Date: January 2008 End Date: December 2009 Key Personnel: W. Gregory Hood, Phd, Senior Restoration Ecologist Project manager and Scientist Will plan and implement the monitoring program, direct fieldwork, analyze data, and report and disseminate results. Problem Statement Restoration monitoring is sometimes perceived as not having delivered value to management agencies. Consequently, agencies are reluctant to fund monitoring, preferring instead to fund only restoration. The criticism of monitoring is valid and the causes of its failure are multiple, among them: [a] funding for monitoring is often inconsistent or unreliable (which leads to inconsistent and unreliable monitoring, and a catch-22 situation); [b] monitoring is often mere comparison of reference and restoration sites rather than hypothesis testing, [c] monitoring often requires long-term observation (patience) incompatible with short-term performance requirements of many agencies; and [d] monitoring often does not deliver useful information on which agencies can act. In support of Chinook salmon recovery, we propose to deliver value through a monitoring project that develops and tests restoration design and planning tools that could be used throughout Puget Sound.