A Novel Three-Axis Cylindrical Hohlraum Designed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1958 Geneva Conference on the Discontinuation of Nuclear Weapons

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Presidential Decisions on Stockpile Stewardship Test-Based Stewardship and the Cold War Transitioning to Stockpile Stewardship Science: Research, Development, and Technology Deterrence and the Life Extension Program Global Nuclear Security Timeline of U.S. Stockpile Stewardship Innovation The Path Forward Today, I am announcing my “decision to negotiate a true zero-yield comprehensive test ban.” U.S. President Bill Clinton, August 11, 1995 The National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 1994 (P.L. 103-160) estab- lished the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) to sustain the nuclear deterrent in the absence of nuclear explosive testing. The SSP supports U.S. national security missions through leading-edge scientific, engineering, and technical tools and expertise – a U.S. response to the end of the Cold War and the need to remake the global nuclear landscape. One year later, on August 11, 1995, Presi- dent Bill Clinton announced that the United States would support a “zero yield” Compre- hensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT): “I am assured by the Secretary of Energy and the Directors of our nu- clear weapons labs that we can meet the challenge of maintaining our nuclear deterrent under a Compre- hensive Test-Ban Treaty through a Science-Based Stockpile Stewardship program without nuclear testing.” This year, the Nation and the Department of Energy (DOE) celebrate the 20th anniver- sary of that announcement and the scientific and technical capabilities that have devel- oped to support this policy direction. The national investment in stockpile stewardship has enabled resolution of many stockpile issues and provided more detailed knowledge than what could have been attained through nuclear explosive testing. -

Memorandum to Participants JASON 1994 Summer Study

Hydronnclear Testing and the Comprehensive Test Ban: Memorandum to Participants JASON 1994 Summer Study Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. 1350 New York Avenue, NW, Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20005 Tel (main): (202) 783-7800 Cochran (direct dial): (202) 624-9329 Paine (direct dial): (202) 624-9350 Fax: (202) 783-5917 INTERNET: [email protected] Although no commonly accepted defInition exists, a "hydronuclear test" may be generally described as a nuclear weapons test, or high-explosive driven criticality experiment, characterized by a nuclear energy release that is insuffIcient to heat the core material to the plasma temperatures that would cause it to explode "like a bomb." In such a test, the TNT equivalent energy release from fission would therefore not exceed the amount released by the chemical high explosive used to compress the fIssile material, and could be considerably ,less. Nuclear-weapon states, and possibly other states, also perform high-explosive driven implosion experiments using fusjon material, although" these' are not nonnally characterized as "hydronuclear tests". Hydronuclear tests can serve a useful role in the development of the full spectrum of unboosted fIssion weapons, including'first generation nuclear weapons of the implosion type with yields in the 5 to 30 kiloton range, more sophisticated designs with yields up to about a megaton, and advanced micro-nuclear weapons with yields of 5 to 500 tons. For pure fIssion weapons hydronuclear tests can be used to:' * optimize the timing of initiation of the -

Dangerous Thermonuclear Quest: the Potential of Explosive Fusion Research for the Development of Pure Fusion Weapons

Dangerous Thermonuclear Quest: The Potential of Explosive Fusion Research for the Development of Pure Fusion Weapons Arjun Makhijani, Ph.D. Hisham Zerriffi July 1998 Minor editing revisions made in 2003. Table of Contents Preface i Summary and Recommendations v Summary of Findings vi Recommendations vii Chapter 1: Varieties of Nuclear Weapons 1 A. Historical Background 1 B. Converting Matter into Energy 4 C. Fission energy 5 D. Fusion energy 8 E. Fission-fusion weapons 16 Chapter 2: Inertial Confinement Fusion Basics 19 A. Deposition of driver energy 24 B. Driver requirements 25 C. Fuel pellet compression 27 D. Thermonuclear ignition 29 Chapter 3: Various ECF Schemes 31 A. Laser Drivers 32 B. Ion Beam Drivers 34 1. Heavy Ion Beams 35 a. Induction Accelerators 36 b. Radio-Frequency Accelerators 36 2. Light Ion Beams 37 C. Z-pinch 39 D. Chemical Explosives 40 E. Advanced materials manufacturing 42 1. Nanotechnology 42 2. Metallic Hydrogen 45 Chapter 4: The Prospects for Pure Fusion Weapons 47 A. Requirements for pure fusion weapons 47 B. Overall assessment of non-fission-triggered nuclear weapons 48 1. Ignition 48 2. Drivers 53 C. Overall technical prognosis for non-fission triggered nuclear weapons 54 D. Fusion power and fusion weapons - comparative requirements 56 Chapter 5: Nuclear Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Issues Related to Explosive Confinement Fusion 59 A. The Science Based Stockpile Stewardship Program 62 1. Reliability 62 a. Reliability definition 63 b. Future reliability problems 64 c. Relevance of NIF to reliability of the current stockpile 65 2. The US laser fusion program as a weapons development program 65 3. -

Nuclear Weapons Journal PO Box 1663 Mail Stop A142 Los Alamos, NM 87545 WEAPONS Issue 2 • 2009 Journal

Presorted Standard U.S. Postage Paid Albuquerque, NM nuclear Permit No. 532 Nuclear Weapons Journal PO Box 1663 Mail Stop A142 Los Alamos, NM 87545 WEAPONS Issue 2 • 2009 journal Issue 2 2009 LALP-10-001 Nuclear Weapons Journal highlights ongoing work in the nuclear weapons programs at Los Alamos National Laboratory. NWJ is an unclassified publication funded by the Weapons Programs Directorate. Managing Editor-Science Writer Editorial Advisor Send inquiries, comments, subscription requests, Margaret Burgess Jonathan Ventura or address changes to [email protected] or to the Designer-Illustrator Technical Advisor Nuclear Weapons Journal Jean Butterworth Sieg Shalles Los Alamos National Laboratory Mail Stop A142 Science Writers Printing Coordinator Los Alamos, NM 87545 Brian Fishbine Lupe Archuleta Octavio Ramos Los Alamos National Laboratory, an affirmative action/equal opportunity employer, is operated by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of the US Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-06NA25396. This publication was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the US Government. Neither Los Alamos National Security, LLC, the US Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees make any warranty, express or implied, or assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed or represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, the US Government, or any agency thereof. -

Progress of Indirect Drive Inertial Confinement Fusion in the Us

Kline DOI:10.1088/1741-4326/ab1ecf OV/2-5 Progress of Indirect Drive Inertial Confinement Fusion in the USA J. L. Kline1, S. H. Batha1, L. R. Benedetti2, D. Bennett2, S. Bhandarkar2, L. F. Berzak-Hopkines2, J. Biener2, M. M. Biener2, R. Bionta2, E. Bond2, D. Bradley2, P. A. Bradley1, T. Braun2, D. A. Callahan2, J. Caggiano2, T. Cardenas2, C. Cerjjan2, B. Cagadas2, D. Clark2, C. Castro2, W. S. Daughton1, E. L. Dewald2, T. Döppner2, L. Divol2, E. S. Dodd1, R. Dylla-Spears2, M. Eckart2, D. Edgell3, M. Farrell4, J. Field2, F. Fierro1, D. N. Fittinghoff2, M. Gatu-Johnson5, S. Johnson2, G. Grim2, N. Guler1, S. Haan2, B. M. Haines1, C. E. Hamilton1, A. V. Hamza2, E. P. Hartouni2, R. Hatarik2, K. Hernderson1, H. W. Herrmann1, D. Hinkel2, D. D. Ho2, M. Hohenburger2, D. Hoover4, H. Huang4, M. L. Hoppe4, O. A. Hurricane2, N. Izumi2, O. S. Jones2, S. Khan2, B. J. Kozioziemski2, C. Kong2, J. Kroll2, G. A. Kyrala2, R. J. Leeper2, S. LePape2, E. Loomis1, T. Ma2, A. J. Mackinnon2, A. G. MacPhee2, S. MacLaren2, L. Masse2, J. McNaney2, N. B. Meezan2, J. F. Merrill1, E. C. Merritt1, J. L. Milovich2, D. S. Montgomery1, J. Moody2, A. Nikroo2, J. Oertel1, R. E. Olson1, A. Pak2, S. Palaniyappan1, P. Patel2, B. M. Patterson1, T. S. Perry1, R. R. Peterson1, E. Piceno2, J. E. Ralph2, R. B. Randolph1, N. Rice4, H. F. Robey2, J. S. Ross2, J. R. Rygg3, M. R. Sacks1, J. Sauppe1, J. Salmonson2, D. Sayre2, J. D. Sater2, M. Schneider2, M. Schoff4, D. W. Schmidt1, S. -

Report Is Available on the UCS Website At

Making Smart Security Choices The Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex Making Smart SecurityChoices The Future of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex Lisbeth Gronlund Eryn MacDonald Stephen Young Philip E. Coyle III Steve Fetter OCTOBER 2013 Revised March 2014 ii UNION OF CONCERNED SCIENTISTS © 2013 Union of Concerned Scientists All rights reserved Lisbeth Gronlund is a senior scientist and co-director of the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) Global Security Program. Eryn MacDonald is an analyst in the UCS Global Security Program. Stephen Young is a senior analyst in the UCS Global Security Program. Philip E. Coyle III is a senior science fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Steve Fetter is a professor in the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. The Union of Concerned Scientists puts rigorous, independent science to work to solve our planet’s most pressing problems. Joining with citizens across the country, we combine technical analysis and effective advocacy to create innovative, practical solutions for a healthy, safe, and sustainable future. More information about UCS and the Global Security Program is available on the UCS website at www.ucsusa.org/nuclear_weapons_and_global_security. The full text of this report is available on the UCS website at www.ucsusa.org/smartnuclearchoices. DESIGN & PROductiON DG Communications/www.NonprofitDesign.com COVER image Department of Defense/Wikimedia Commons Four B61 nuclear gravity bombs on a bomb cart at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. Printed on recycled paper. MAKING SMART SECURITY CHOICES iii CONTENTS iv Figures iv Tables v Acknowledgments 1 Executive Summary 4 Chapter 1. -

UNRESOLVED ISSUES Related to the NATIONAL IGNITION FACILITY

UNRESOLVED ISSUES Related to the NATIONAL IGNITION FACILITY Thomas B. Cochran Christopher E. Paine Nuclear Program Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc 1350 New York Avenue, NW, Suite 300 Washington, D.C. 20005 Tel: 202-783-7800 FAX: 202-783-5917 INTERNET: [email protected] A commitment to the National Ignition Facility (NIF) beyond limited design work is premature and should not go forward unless further research and evaluation leads to favorable resolution of a number of outstanding issues. The most critical questions are: 3. Can Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (llNL) construct NIF for $1.1 billion as advertised? 4. Is NIF the best facility for exploring the feasibility of inertial confinement fusion (ICF)for civil energy applications? 5. Will NIF contribute significantly to the resolution of technical issues that may arise in the future concerning the reliability or safety of the existing U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile? 6. Can the U.S. conduct a large national ICF program, with a specific emphasis on maintaining computer modeling skills relevant to the design of nuclear weapons, without continuing to generate and release data and computer codes that will enhance thermonuclear weapons research and design capabilities in threshold and non-weapons states? None of these questions can be answered "yes" with high confidence. Rather, as indicated below, "no" or "probably not" now appears to be the more appropriate answer to each of the above questions. The principal design objective of NIF is to achieve ignition and moderate gain (1-10) in hohlraum targets. The design criteria, and in particular the driver energy of 1.8 MJ, were developed by extrapolating from two sources: upwards from the data provided by NOVA experiments, and downwards from the large high-gain hohlraum capsules successfully ignited in the formerly classified series of Halite-Centurion experiments using abundant X- radiation from underground nuclear testsasthe "driver." However, in both cases,the target designswere significantly different from those proposed for use in NIF. -

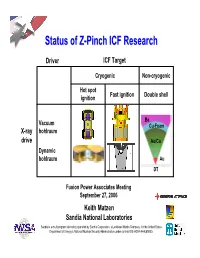

Status of Z-Pinch ICF Research

StatusStatus ofof Z-PinchZ-Pinch ICFICF ResearchResearch Driver ICF Target Cryogenic Non-cryogenic Hot spot Fast ignition Double shell ignition Be Vacuum Cu-Foam X-ray hohlraum drive Au/Cu Dynamic hohlraum Au DT Fusion Power Associates Meeting September 27, 2006 Keith Matzen Sandia National Laboratories Sandia is a multiprogram laboratory operated by Sandia Corporation, a Lockheed Martin Company, for the United States Department of Energys National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-AC04-94AL85000. The goal of the Pulsed Power ICF program is to validate a High Yield target design Advanced concepts (Fast Ignitor) Dynamic hohlraum Double-ended hohlraum Efficiency Risk We are presently studying 3 High Yield target concepts 2 Pulsed-power provides compact, efficient, power amplification 17 m radius Z 200 150 x ray output vacuum ~1.6 MJ 100 ~200 TW water Marx Electrical to x-ray energy Power (TW) 50 Conversion efficiency ~ 15% 11.4 MJ 0 00.511.5Efficiency Low Cost Time (µs) 3 Indirect drive ICF: a spherical capsule is imploded by z-pinch-produced x-rays contained in a hohlraum JxB Target heating Compression Ignition Burn 4 The double-ended hohlraum high yield concept separates capsule, hohlraum, and z-pinch physics issues z-pinch energetics pinch simultaneity pinch balance hohlraum energetics radiation symmetry hohlraum coupling pulse shaping capsule physics 5 A focused effort began in Sept 2005 to create a modern reference design for the double-ended hohlraum (DEH) ~35 mm Key results of initial scoping study: 25 mm • 400 MJ yield capsule • 16 MJ total x-ray energy output from 2 pinches • 2 x 62 MA currents required with 100 ns rise time • Pulse shaping via multi-shell z-pinch load design • Spoke x-ray transmission of > 60% required • Pinch power balance of 7% required Integrated 2D simulations with capsule implosion/ignition/burn were not achieved in the 1999 study, mainly due to symmetry issues 6 2D Lasnex simulations of hohlraum energetics and symmetry have been validated in DEH experiments on Z • Consistency of z-pinch and hohlraum M. -

Super Laser at the NIF Educator Guide

Super Laser at the NIF Educator Guide A resource for using QUEST video and audio in the classroom Watch it online http://www.kqed.org/quest/television/view/842 | 11:00 minutes Listen to it online http://www.kqed.org/quest/radio/view/726 | 5:45 minutes QUEST SUBJECTS PROGRAM NOTES It's the largest laser beam in the world and it's being built in the Bay Area. The National Life Biology Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory will shoot tremendous bursts Science Health Environment of energy at an area the size of a pencil eraser. The goal? To recreate fusion, which powers the sun and some nuclear bombs, perhaps harnessing a new source of clean Earth Geology energy for the 21st Century. Science Weather Astronomy In this segment you’ll find… .an explanation of nuclear fission and fusion ۞ Physical Physics .Science Chemistry ۞ how lasers work Engineering why some scientists think nuclear fusion may be the ۞ answer to clean energy. CA SCIENCE STANDARDS Grades 9-12 Chemistry TOPIC BACKGROUND Conservation of Matter and Stoichiometry Nuclear fusion is the process that powers the sun and stars. In a fusion reaction, two 3. (a) writing balanced lighter hydrogen nuclei combine together, or fuse, to form an atom of helium with a equations somewhat larger nucleus. The easiest fusion reaction to replicate is to combine two Chemical isotopes of hydrogen – deuterium, which has a nucleus composed of one neutron and Thermodynamics one proton, and tritium which has two neutrons and one proton in its nucleus. The 7. (a,b) motion of resulting products are one atom of helium (with two protons and two neutrons), one 2 molecules; exothermic neutron, and the release of energy as described by Einstein’s famous equation E=mc . -

The Question of Pure Fusion Explosions Under the CTBT

~, ,:' ., Science & Global Security. 1998. Volume 7. pp.129-150 @ 1998 OPA (OverseasPublishernAssociation) N.V. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under Photocopying pennitted by license only the Gordon and Breach Publishernimprint. Printed in India The Question of Pure Fusion Explosions Under the CTBT Suzanne L. Joneso and Frank N. von Hippelb Fusion research involving implosions of deuterium-tritium targets driven by laser or particle beams appears to be widely acceptedas not prohibited under the Comprehen- sive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). Researchon fusion involving implosions driven by other means is underway in civilian and military laboratories in the US and other countries and could result in small (up to perhaps a few tons TNT equivalent) explosive fusion energy releases. However, the status of such experiments under the CTBT has not been clearly defined. Until the potential for this research to lead to the development of pure fusion weaponshas been openly reviewed and an appropriate policy governing its conduct is established in the context of the CTBT, such experiments should be subject to two interim limits: (1) a maximum of -1014neutrons produced; and (2) a ban on the use of tritium. INTRODUCTION The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) bans "any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion." However, neither the Treaty text nor the public negotiating record provide a technically precise understanding of the boundary between prohibited nuclear explosions and not-prohibited activities. There are gray areas that states will need to address in the context of ratification deliberations and for internal planning purposes. In the case of fission explosions,the United States has imposed criticality as.its own dividing line between a "nuclear explosion" and something less than that.! A policy regarding permitted fusion experiments is also needed.Were it possible to create compact, pure-fusion nuclear explosives, their detonation would obviously be prohibited by the Treaty. -

Analysis of Heavy Ion Fusion Targets

Particle Accelerators, 1992, Vols. 37-38, pp. 519-530 © 1992 Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, S.A. Reprints available directly from the publisher Printed in the United Kingdom Photocopying permitted by license only ANALYSIS OF HEAVY ION FUSION TARGETS J. MEYER-TER-VEHN and M. MURAKAMI Max-Planck-Institut fur Quantenoptik, D-8046 Garching, FRG. (Received 7 January 1990) Indirectly driven targets for heavy ion fusion are discussed. In particular, results concerning the beam/x-ray conversion efficiency and target gain are given; r1.5R scaling is derived analytically. 1 INDIRECT DRIVE FOR HEAVY ION FUSION For future progress in heavy ion fusion, it is indispensible to discuss the physics and the design of indirectly driven targets. Indirect drive may well be the superior option for imploding fusion capsules with heavy ion beams at the required level of spherical symmetry. Direct illumination of a capsule with not more than 1-2% rms asymmetry is already very difficult to achieve with lasers, but it is almost impractical with stiff heavy ion beams that deposit their energy deeply inside solid material. Since the concept of indirect drive is to convert the beam energy first into thermal x-rays in converter elements which are separated from the fusion capsule, the geometry of beam/target interaction and also the requirements on deposition power are quite different from direct drive. Details of target design therefore matter for both heavy ion driver development and relevant beam/target interaction experiments1. In this paper we start with a general discussion ofdifferent target designs in Section 2. A tutorial introduction to inertial confinement fusion (ICF) was given recently in Ref. -

Fourth Generation Nuclear Weapons: Military Effectiveness and Collateral Effects

Fourth Generation Nuclear Weapons: Military effectiveness and collateral effects Andre Gsponer Independent Scientific Research Institute Box 30, CH-1211 Geneva-12, Switzerland Version ISRI-05-03.17 February 2, 2008 Abstract The paper begins with a general introduction and update to Fourth Gen- eration Nuclear Weapons (FGNW), and then addresses some particularly important military aspects on which there has been only limited public discussion so far. These aspects concern the unique military character- istics of FGNWs which make them radically different from both nuclear weapons based on previous-generation nuclear-explosives and from conven- tional weapons based on chemical-explosives: yields in the 1 to 100 tons range, greatly enhanced coupling to targets, possibility to drive powerful shaped-charge jets and forged fragments, enhanced prompt radiation effects, reduced collateral damage and residual radioactivity, etc. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Second and third generation nuclear weapons arXiv:physics/0510071v5 [physics.soc-ph] 26 Feb 2006 2.1. Boosting 2.2. Two-stage thermonuclear weapons 2.3. Third generation nuclear weapons 2.4. The “Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator” debate 1 3. Fourth generation nuclear weapons 3.1. Inertial confinement fusion experiments and FGNW 3.2. Microexplosions and high energy-density 3.3. Petawatt-class lasers (superlasers) 3.4. Nuclear isomers 3.5. Antimatter 3.6. Micro/nano-technology and nuclear bullets 3.7. Pure antimatter bombs? 4. Target coupling 4.1. Initial energy from conventional or nuclear weapons 4.2. Initial work from conventional or nuclear weapons 4.3. Coupling to homogeneous and heterogeneous targets 4.4. FGNW coupling 5. Thermonuclear-driven jets and projectiles 5.1.