Critical Notices Oracles of Orpheus? the Orphic Gold Tablets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Ritual for the Dead: the Tablets from Pelinna (L 7Ab)

CHAPTER TWO A RITUAL FOR THE DEAD: THE TABLETS FROM PELINNA (L 7AB) Translation of tablets L 7ab from Pelinna The two tablets from Pelinna (L 7a and 7b) were found in Thessaly in 1985, on the site of ancient Pelinna or Pelinnaion. They were placed on the breast of a dead female, in a tomb where a small statue of a maenad was also found (cf. a similar gure in App. II n. 7). Published in 1987, they revolutionized what had been known and said until then about these texts, and contributed new and extremely important view- points.1 They are in the shape of an ivy leaf, as they are represented on vase paintings,2 although it cannot be ruled out that they may represent a heart, in the light of a text by Pausanias that speaks of a “heart of orichalcum” in relation to the mysteries of Lerna.3 Everything in the grave, then, including the very form of the text’s support, suggests a clearly Dionysiac atmosphere, since both the ivy and the heart evoke the presence of the power of Dionysus. The text of one of the tablets is longer than that of the other. It has been suggested4 that the text of the shorter tablet was written rst, and since the entire text did not t, the longer one was written. We present the text of the latter:5 1 These tablets were studied in depth by their \ rst editors Tsantsanoglou-Parássoglou (1987) 3 ff., and then by Luppe (1989), Segal (1990) 411 ff., Graf (1991) 87 ff., (1993) 239 ff., Ricciardelli (1992) 27 ff., and Riedweg (1998). -

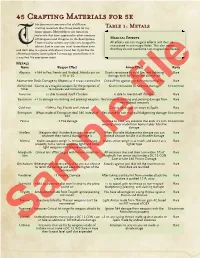

45 Crafting Materials for 5E His Document Contains a List of Different Crafting Materials That I Have Made for My Table 1: Metals Home Games

45 Crafting Materials for 5e his document contains a list of different crafting materials that I have made for my Table 1: Metals home games. Most of these are based on materials that have appeared in other versions of Dungeons and Dragons. In the descriptions, Magical Effects I have tried to remove any reference to specific All effects are non-magical effects and thus are Tplanes. Just in case you want to use them as-is maintained in anti-magic fields. This also means and don't play in a game with planar travel, but if you like the that they do not overcome non-magical resistances effects but not the descriptions I encourage you to flavor it in a way that fits your game most. Metals Name Weapon Effect Armor Effect Rarity Abyssus +1d4 to Fey, Fiends and Undead, Attacks crit on Grants resistance to cold, fire, and lightning Rare a 19 or 20 damage dealt by fiends and elementals Adamantine Deals Damage to Objects as if it was a critical hit Critical Hits against you turn into normal hits Rare Alchemical Counts as a magical weapon for the purposes of Grants resistance to Necrotic damage Uncommon Silver resistances and immunities Aururum Is able to mend itself if broken Is able to mend itself if broken Rare Baatorium +1 to damage on slashing and piercing weapons Resistance to slashing and piercing damage from Rare non-magical weapons Cold Iron +1d4 to Fey, Fiends and Undead Grants advantage on saves vs Spells Rare Entropium Whips made of Entropium deal 1d6 instead of Resistance to non-magical bludgeoning damage Uncommon 1d4 Fevrus +1 Fire damage Immune to Cold, any creature that ends it’s turn Uncommon wearing armor made from Fevrus takes 1d6 Fire damage. -

Decodingthedelugever25.4Vol1free (Pdf) Download

DECODING THE DELUGE AND FINDING THE PATH FOR CIVILIZATION Volume I Of Three Volumes by David Huttner Version 25.4; Release date: March 7, 2020 Copyright 2020, by David Huttner I hereby donate this digital version of this book to the public domain. You may copy and distribute it, provided you don’t do so for profit or make a version using other media (e.g. a printed or cinematic version). For anyone other than me to sell this book at a profit is to commit the tort of wrongful enrichment, to violate my rights and the rights of whomever it is sold to. I also welcome translations of the work into other languages and will authorize the translations of translators who are competent and willing to donate digital versions. Please email your comments, questions and suggestions to me, David Huttner, mailto:[email protected] or mailto:[email protected] . Cover by A. Watson, Chen W. and D. Huttner Other Works by David Huttner, soon to be Available Autographed and in Hardcopy at http://www.DavidHuttnerBooks.com , Include: Decoding the Deluge and finding the path for civilization, Volumes 2 & 3 Irish Mythology passageway to prehistory Stage II of the Nonviolent Rainbow Revolution The First Christmas (a short play) Making the Subjective and Objective Worlds One Just Say No to Latent Homosexual Crusades Social Harmony as Measured by Music (a lecture) The Spy I Loved secrets to the rise of the Peoples Republic of China The Selected Works of David Huttner, Volumes 1 and 2 Heaven Sent Converting the World to English 2 This work is dedicated to Robert Teyema, a Chicago policeman. -

Poseidon's Paradise

" BANCROFT IA. LIBRARY 0- THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY ir OF CALIFORNIA V 5^;-< f . ,JS^ , . yfe%T>^ AjLj^r : ^^|: ^^^p^^fe^ %^f)|>^^y^^ V>J? r ^ / -Vr T^^^S?^^ yiivV(^ " " i^V^ ^^- r s V V v '4- ^ ^r^--^r^ %^<^(.|^^ - i!lSSsSS I^^^P^P, ^tmws-^- : Adapted from Ignatius Donnelly's map of Atlantis, page 47 of the "Atlantis," by per- lission of Harper & Brothers. Cleit, Chimo, and Luith are names fictitious. POSEIDON'S PARADISE The Romance of Atlantis BY ELIZABETH G. BIRKMAIER 415 MONTGOMERY STREET 1892. \7 of COPYRIGHT, 1892, BY ELIZABETH G. BIRKMAIER. All Rights Reserved. T Uf: CONTENTS. PAGE. I. A DECLARATION OF WAR . 5 II. QUEEN ATLANA 20 III. ATLANTIS VERSUS PELASGIA 29 IV. THE PELASGIAN CAPTIVES 38 V. THE ABDUCTION 55 VI. THE VOICE 67 VII. THE TEMPLE 79 VIII. POSEIDON'S FESTIVAL DAY 98 IX. THE 'SILENT PRIEST' ;.. in X. LIGHT ON THE PATH. 127 XI. THE HAPPENING OF THE UNEXPECTED 142 XII. THE EARTHQUAKE CONFOUNDS 153 XIII. IN THE 'DEEPS' 162 XIV. A TIMELY TORRENT 176 XV. THE ALTAR FIRES Go OUT 198 XVI. THE SILENT ONE SPEAKS 217 XVII. THE SINKING OF THE ISLAND 237 ' XVIII . PYRRHA 253 XIX. THE BEGINNING OF PEACE 269 XX. HAPPY PAIRS 275 XXI. IN PELASGIA 291 "Time dissipates to shining ether the solid angularity offacts.. No anchor, no cable, nofences avail to keep a fact a fact. Babylon, and Troy, and Tyre, and even early Rome are passing into fiction. The Garden of Eden, the sun standing still in Gibeon, is poetry thenceforward to all nations' ' EMERSON. -

Episode 10 - Culture Fit

Fun City Ventures - Episode 10 - Culture Fit [ Transcription by Matthew Wang Downing ] [ 00:00:00 ] [ Intro Theme begins ] > Molly Templeton / "Artemis": [ IC ] In the early 21st century, magic reawakened on Earth, and alongside it, a new human race, with orcs, elves, trolls, dwarves, and others. Humanity became metahumanity. As technology proliferated and greatly advanced in the awakened world, global megacorporations seized ever more power, becoming de facto states with their own laws, courts, and armed forces. The corporations attempt to control all aspects of modern life. This has led to a vast and complex criminal underground which works for and against corporate interests. The independent career criminals who do what others can't or won't are called Shadowrunners. The year is 2101. Welcome to Fun City. [ Intro Theme ends ] [ Main Theme begins ] > Mike Rugnetta / G.M.: Previously on Fun City, the team is hired by Mo Ashina of Combinatorial Limited to disgrace police union bureaucrat Verne Sollix, and end his architecting a strike of the NYPD Incorporated Police Force. Upon confrontation at the Police Expo, Verne claims that triple-A biotechnology megacorporation, Evo, is experimenting on police, who are contractually obligated to see the company for medical care. A strike is the only way to get leverage and stop them. He offers to hire the team, but a riot breaks out. Viv melts Cairn Holbrook, an NYPD reserve detection mage, and Luxe takes a call from Yuri, who has another job for them. Frazzled - but free - the team heads to The Ball Pit to regroup. There, they meet a many-armed man, who shows them an illusion of a horrifically dismembered Gabe. -

First Discovery of Orichalcum Ingots from the Remains of a 6Th Century Bc Shipwreck Near Gela (Sicily) Seabed

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 17, No 2, (2017), pp. 11-18 Copyright © 2017 MAA Open Access. Printed in Greece. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.581716 FIRST DISCOVERY OF ORICHALCUM INGOTS FROM THE REMAINS OF A 6TH CENTURY BC SHIPWRECK NEAR GELA (SICILY) SEABED Eugenio Caponetti*1,2,3, Armetta Francesco1, Delia Chillura Martino1,2, Maria Luisa Saladino1, Stefano Ridolfi3, Gabriella Chirco3, Mario Berrettoni*4, Paolo Conti5, Nicolò Bruno6 and Sebastiano Tusa6 1Dipartimento Scienze e Tecnologie Biologiche, Chimiche e Farmaceutiche – STEBICEF, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Parco d’Orleans II, Viale delle Scienze pad. 17, I-90128, Palermo, Italy 2Centro Grandi Apparecchiature-ATeN Center, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Via F.Marini 14, I-90128, Palermo, Italy 3Labor Artis CR Diagnostica, Viale delle Scienze pad. 16, I-90128, Palermo, Italy 4Dipartimento di Chimica Industriale "Toso Montanari", UoS campus di Rimini, Università di Bologna, Viale dei Mille 39, I-40196, Rimini, Italy 5Scuola di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università di Camerino, Piazza dei Costanti, 62032 Camerino, Italy 6Soprintendenza del mare della Regione Siciliana, Palazzetto Mirto Via Lungarini 9, I-90133 Palermo, Italy Received: 23/03/2017 Corresponding authors: Eugenio Caponetti ([email protected]), Mario Berrettoni ([email protected]) Accepted: 20/04/2017 ABSTRACT Ingots recently recovered from the seabed near Gela, a major harbour of Sicily, reveal an unexpected side of ancient metallurgy. The ingots were found near remains of a ship and earthenware dated around the end of the VI century BC and probably coming from the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean sea. The ingots were analysed by means of X-Ray Fluorescence spectroscopy via a portable spectrometer. -

Themes of Polemical Theology Across Early Modern Literary Genres

Themes of Polemical Theology Across Early Modern Literary Genres Themes of Polemical Theology Across Early Modern Literary Genres Edited by Svorad Zavarský, Lucy R Nicholas and Andrea Riedl Themes of Polemical Theology Across Early Modern Literary Genres Edited by Svorad Zavarský, Lucy R Nicholas and Andrea Riedl This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Svorad Zavarský, Lucy R Nicholas, Andrea Riedl and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8735-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8735-9 This collection of essays forms part of the research project “Polemical Theology and Its Contexts in Early Modern Slovakia” (VEGA 2/0170/12) carried out at the Ján Stanislav Institute of Slavonic Studies of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, in the years 2012–2015. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... xi Preface ...................................................................................................... xiii Prolusio by Way of Introduction .............................................................. -

GREEK and ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek

GREEK AND ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek coins were struck from blank pieces of metal first prepared by heating and casting in molds of suitable size. At the same time, the weight was adjusted. Next, the blanks were stamped with devices which had been prepared on the dies. The lower die, for the obverse, was fixed in the anvil; the reverse was attached to a punch. The metal blank, heated to soften it, was placed on the anvil and struck with the punch, thus producing a design on both sides of the blank. Weights and Values The values of Greek coins were strictly related to the weights of the coins, since the coins were struck in intrinsically valuable metals. All Greek coins were issued according to the particular weight system adopted by the issuing city-state. Each system was based on the weight of the principal coin; the weights of all other coins of that system were multiples or sub-divisions of this major denomination. There were a number of weight standards in use in the Greek world, but the basic unit of weight was the drachm (handful) which was divided into six obols (spits). The drachm, however, varied in weight. At Aigina it weighed over six grammes, at Corinth less than three. In the 6th century B.C. many cities used the standard of the island of Aegina. In the 5th century, however, the Attic standard, based on the Athenian tetradrachm of 17 grammes, prevailed in many areas of Greece, and this was the system adopted in the 4th century by Alexander the Great. -

Ebook Download the Atlantis World

THE ATLANTIS WORLD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK A. G. Riddle | 368 pages | 13 Aug 2015 | Head of Zeus | 9781784970130 | English | London, United Kingdom The Atlantis World PDF Book The Longest Rivers Of Asia. A similar theory had previously been put forward by a German researcher, Rainer W. Kate Warner and MacGyver wannabee David Vale, as they fought an unseen organization while running for their lives. Aside from Plato's original account, modern interpretations regarding Atlantis are an amalgamation of diverse, speculative movements that began in the sixteenth century, [50] when scholars began to identify Atlantis with the New World. For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot. Similar Products. In the dialogue, Critias says, referring to Socrates' hypothetical society:. I especially liked the technology. The choices you make here will apply to your interaction with this service on this device. The orders are seek and destroy, and Dorian has been promised that his own answers and salvation lie on the other side. The scenes he had he totally stole. The usurping poisoner is poisoned in his turn, following which the continent is swallowed in the waves. Like its predecessors, The Atlantis World w In the final book of the series, The Atlantis World attempts to explore the popular myth of the origins of the human race. My only interest was to see how it ended and to finally get it out of the way so I can start something else that won't make me go bald. -

The Empire Strikes: the Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C

The Empire Strikes: The Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C. – A.D. 68 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by David Schwei M.A., University of Cincinnati, December 2012 B.A., Emory University, May 2009 Committee Chairs: Peter van Minnen, Ph.D Barbara Burrell, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Coins permeated the Roman Empire, and they offer a unique perspective into the ability of the Roman state to implement its decisions in Italy and the provinces. This dissertation examines how this ability changed and grew over time, between 60 B.C. and A.D. 68, as seen through coin production. Earlier scholars assumed that the mint at Rome always produced coinage for the entire empire, or they have focused on a sudden change under Augustus. Recent advances in catalogs, documentation of coin hoards, and metallurgical analyses allow a fuller picture to be painted. This dissertation integrates the previously overlooked coinages of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt with the denarius of the Latin West. In order to measure the development of the Roman state’s infrastructural power, this dissertation combines the anthropological ideal types of hegemonic and territorial empires with the numismatic method of detecting coordinated activity at multiple mints. The Roman state exercised its power over various regions to different extents, and it used its power differently over time. During the Republic, the Roman state had low infrastructural minting capacity. -

Hierophant's Staff (Orichalcum Wrackstaff with Integrated

Hierophant’s Staff (Orichalcum wrackstaff with Vestment of Holy Vigilance (Artifact ● or ●●) integrated Metasorcerous Phylactery, Artifact ●●) Artifact ●: Staff: Allows reflexively hearing prayers directed to the Heavy weapon (+2 damage, -1 Initiative). Size 1. wearer: either all, the loudest, or none, as the No penalty for its Size (1). Attunement (+1). wearer desires at the moment (3). Metasorcerous Phylactery: Artifact ●●: +3 Alternative possible Gift allocations (1x3) In addition, allows the wearer to telepathically Apply one to the spell you use (3 each): compose and send a response immediately after +2 to the Shaping Roll receiving the prayer; it costs 1m to be able to do +2 to the spell’s Effect if it is a dice pool that for a scene. The supplicant receives a vision +2 Reaching to the spell’s range or the of the Exalt’s iconic anima speaking the Chosen’s point of origin for the area spells. words in thunderous proclamation. As this power +2 Paced to the spell’s duration in the is reliant not on the wearer, but on the Creation’s tactical time, or +2 Intervals of its natural metaphysical principles to function, and is Paced in Narrative time. independent of the wearer’s own powers; it does not require much, but it is treated as a normal Requires a Heartstone ●, ●●, or ●●● (+2 averaged) prayer link. Useable (Heartstone’s Rating) times per scene (+1) Requires Attunement (+1) Some uses of the Phylactery are very complex Can only be attuned by the wearer appropriate and require time to master. This is represented by for the material (+1) the following learnable Evocations. -

Reconsidering the Interpretation and Dating of Ancient Coins: the Case of Bronze Coins from Dodona in the Name of Menedemos Argeades

GEPHYRA 13, 2016, 127-148 Reconsidering the Interpretation and Dating of Ancient Coins: The Case of Bronze Coins from Dodona in the Name of Menedemos Argeades Atalante BETSIOU Numismatic studies on the coin production of ancient Epirus and Corinthian colonies in Illyria have made visible progress over recent years. A contribution to the chronology of the bronze coin- age of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium is due to the scholars S. Gjongecaj and O. Picard1, while G. Petrányi has undertaken the study of silver denominations2. Despite this progress, however, the monograph of P. R. Franke, ‘Die antiken Münzen von Epirus’ (1961), still remains a fundamental reference guide. In his monograph, Franke succeeded, without stratigraphic data, in presenting a comprehensive publication about large quantities of numismatic material from different parts of Epirus and especially from the sanctuary of Dodona. From the late 5th c. BC the sanctuary of Dodona became the political center of the local tribes in Epirus, and under its authority a mint was established. This mint was productive during five peri- ods, described by Franke: a) from the early 4th c. BC until 330 BC, minting silver and bronze issues in the name of the Molossian tribe;3 b) 330-234 BC, for a wider political league, the Epirote Alli- ance; c) 234-168 BC, for the members of the Epirote League; d) 168-148 BC, when a series of heavy bronze issues was minted under the supervision of the priest Menedemos Argeades; and e) after 148 BC for the last emissions of the Epirote League.4 The present paper focuses exclusively on the heavy bronze issues of Dodona, which according to Frankeʼs dating proposal, were minted after the battle of Pydna (168 BC) and before the formation of the Roman province of Macedonia (148 BC).