Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BARGUNA District: AMTALI Upazila/Thana: Slno Eiin Name Of

Upazila/Thana Wise list of Institutes District: BARGUNA Upazila/Thana: AMTALI Slno Eiin Name of the Institution Vil/Road Mobile 1 134886 SOUTH BENGAL IDEAL SCHOOL AND COLLEGE AMTALI 01734041282 2 100022 MAFIZ UDDIN GIRLS PILOT HIGH SCHOOL UPZILA ROAD 01718101316 3 138056 PURBO CHAWRA GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOL PATAKATA 01714828397 4 100051 UTTAR TIAKHALI JUNIOR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL UTTAR TIAKHALI 01736712503 5 100016 CHARAKGACHIA SECONDARY SCHOOL CHARAKGACHIA 01734083480 6 100046 KHAGDON JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL KHAGDON 01725966348 7 100028 SHAHEED SOHRAWARDI SECONDARY SCHOOL KUKUA 01719765468 8 100044 GHATKHALI HIGH SCHOOL GHATKHALI 01748265596 9 100038 KALAGACHIA YUNUS A K JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL KALAGACHIA 01757959215 10 100042 K H AKOTA JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL KALAGACHHIA 01735437438 11 100039 HALIMA KHATUN G R GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL GULISHAMALI 01721789762 12 100034 KHEKUANI HIGH SCHOOL KHEKUANI 01737227025 13 100023 GOZ-KHALI(MLT) HIGH SCHOOL GOZKHALI 01720485877 14 100037 ATHARAGACHIA SECONDARY SCHOOL ATHARAGACHIA 01712343508 15 100017 EAST CHILA RAHMANIA HIGH SCHOOL PURBA CHILA 01716203073,011 90276935 16 100009 LOCHA JUUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL LOCHA 01553487462 17 100048 MODDHO CHANDRA JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL MODDHO CHANDRA 01748247502 18 100020 CHALAVANGA HIGH SCHOOL PRO CHALAVANGA 01726175459 19 100011 AMTALI A.K. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL 437, A K SCHOOL ROAD, AMTALI 01716296310 20 100026 ARPAN GASHIA HIGH SCHOOL ARPAN GASHIA 01724183205 21 100018 TARIKATA SECONDARY SCHOOL TARIKATA 01714588243 22 100014 SHAKHRIA HIGH SCHOOL SHAKHARIA 01712040882 23 100021 CHUNAKHALI HIGH -

Situation Assessment Report in S-W Coastal Region of Bangladesh

Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Change Project (BGD/01/004/01/99) SITUATION ASSESSMENT REPORT IN S-W COASTAL REGION OF BANGLADESH (JUNE, 2009) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) Acknowledgements The present study on livelihoods adaptation was conducted under the project Livelihood Adaptation to Climate Change, project phase-II (LACC-II), a sub-component of the Comprehensive Disaster Management Programme (CDMP), funded by UNDP, EU and DFID which is being implemented by the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) with technical support of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), UN. The Project Management Unit is especially thankful to Dr Stephan Baas, Lead Technical Advisor (Environment, Climate Change and Bioenergy Division (NRC), FAO, Rome) and Dr Ramasamy Selvaraju, Environment Officer (NRC Division, FAO, Rome) for their overall technical guidance and highly proactive initiatives. The final document and the development of the project outputs are direct results of their valuable insights received on a regular basis. The inputs in the form of valuable information provided by Field Officers (Monitoring) of four coastal Upazilas proved very useful in compiling the report. The reports of the upazilas are very informative and well presented. In the course of the study, the discussions with a number of DAE officials at central and field level were found insightful. In devising the fieldwork the useful contributions from the DAE field offices in four study upazilas and in district offices of Khulna and Pirojpur was significant. The cooperation with the responsible SAAOs in four upazilas was also highly useful. The finalization of the study report has benefited from the valuable inputs, comments and suggestions received from various agencies such as DAE, Climate Change Cell, SRDI (Central and Regional offices), and others. -

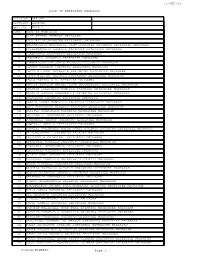

List of Madrsha

List of Madrasha Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100065 WEST CHILA AMINIA FAZIL MADRASAH WEST CHILA 01716835134 2 100067 MOHAMMADPUR MAHMUDIA DAKHIL MADRASAH MOHAMMADPUR 01710322701 3 100069 AMTALI BONDER HOSAINIA FAZIL MADRASHA AMTALI 01714599363 4 100070 GAZIPUR SENIOR FAZIL (B.A) MADRASHA GAZIPUR 01724940868 5 100071 KUTUBPUR FAZIL MADRASHA KRISHNA NAGAR 01715940924 6 100072 UTTAR KALAMPUR HATEMMIA DAKHIL MADRASA KAMALPUR 01719661315 7 100073 ISLAMPUR HASHANIA DAKHIL MADRASHA ISLAMPUR 01745566345 8 100074 MOHISHKATA NESARIA DAKHIL MADRASA MOHISHKATA 01721375780 9 100075 MADHYA TARIKATA DAKHIL MADRASA MADHYA TARIKATA 01726195017 10 100076 DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA RAHMIA DAKHIL MADRASA DAKKHIN TAKTA BUNIA 01718792932 11 100077 GULISHAKHALI DAKHIL MDRASHA GULISHAKHALI 01706231342 12 100078 BALIATALI CHARAKGACHHIA DAKHIL MADRASHA BALIATALI 01711079989 13 100080 UTTAR KATHALIA DAKHIL MADRASAH KATHALIA 01745425702 14 100082 PURBA KEWABUNIA AKBARIA DAKHIL MADRASAH PURBA KEWABUNIA 01736912435 15 100084 TEPURA AHMADIA DAKHIL MADRASA TEPURA 01721431769 16 100085 AMRAGACHIA SHALEHIA DAKHIL AMDRASAH AMRAGACHIA 01724060685 17 100086 RAHMATPUR DAKHIL MADRASAH RAHAMTPUR 01791635674 18 100088 PURBA PATAKATA MEHER ALI SENIOR MADRASHA PATAKATA 01718830888 19 100090 GHOP KHALI AL-AMIN DAKHIL MADRASAH GHOPKHALI 01734040555 20 100091 UTTAR TEPURA ALAHAI DAKHIL MADRASA UTTAR TEPURA 01710020035 21 100094 GHATKHALI AMINUDDIN GIRLS ALIM MADRASHA GHATKHALI 01712982459 22 100095 HARIDRABARIA D.S. DAKHIL MADRASHA HARIDRABARIA -

The Scenario of Seedling Production on Floating Beds in Few Selected Areas of Bangladesh

SAARC J. Agric., 18(1): 239-250 (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.3329/sja.v18i1.48396 Research Article THE SCENARIO OF SEEDLING PRODUCTION ON FLOATING BEDS IN FEW SELECTED AREAS OF BANGLADESH M. Moniruzzaman1*, M.A. Kabir2 and M. Shahjahan3 1Dhaka School of Economics, Eskaton Garden Rd, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh; 2University of Dhaka, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh; 3Bangladesh Livestock Research Institute, Regional Station, Baghabari, Shahjadpur, Sirajganj-6770, Bangladesh ABSTRACT The study was conducted to reveal various seedling production scenario on floating beds including environmental aspects associating seedling production. Data of various seeding production were collected from total 50 households (HHs) of two villages at Nazirpur Upazila in Pirojpur district of Bangladesh by a pre-tested survey questionnaire. The study showed that 68% farmers did seedling production for business purpose, and 30% as both own and business. During floating cultivation on beds about 50% farmers used their own producing seed and 26% from market. The farmers cultivated 21 different types of vegetables and spices seedlings where highest number of seedling was Bottle gourd (19.11%) followed by Papaya (13.82%) and Chili (12.60%). They used urea as a common fertilizer on floating bed which enriched by TSP (46%) and DAP (40%) during cultivation. It was observed that 32% farmers did seedling cultivation solely as own source of money while 26% got the help from NGOs. After end of the cultivation, 25% beds were sold as compost fertilizer for winter cultivation, 5% were used as own field and 17% farmers utilized the fertilizer as both business and own purpose. The study also revealed that, about 64% of respondent farmers were not suffered by any environmental complications. -

Problem Confrontation in Sunflower Cultivation by the Farmers of Nazirpur in Pirojpur A

J. Patuakhali Sci. and Tech. Univ. 2015, 6 (1): 73-83 ISSN 1996-4501 Problem Confrontation in Sunflower Cultivation by the Farmers of Nazirpur in Pirojpur A. Mandal1, A. T. M. S. Haque2, M. G. R. Akanda3 and M. K. Hasan4 Abstract The main focus of the study was to explore the problems confronted by the farmers in sunflower cultivation. Further attempts were made to reveal the determinants of their problem confrontation. Following a multi-stage random sampling method, a total of 92 farmers who have been cultivating sunflower were selected from Nazirpur upazila in Pirojpur in Bangladesh. Firstly, problems were identified through discussions with the farmers and literature reviews. Secondly, interviews with the sunflower cultivators were administered to quantify the problems along with their potential determinants that are stemmed from their socio-economic attributes. The farmers were found to have a moderate level of problems in sunflower cultivation with a small variation (M = 23.62 and SD = 4.55 against a possible score range between 0 to 45). Unweighted ranking of the problems shows that the top three problems out of fifteen were high price of seed, unavailability of improved seed and costly irrigation. Multiple linear regression without addressing the endogeneity problems has confirmed the age, training exposure, cosmopoliteness, knowledge and risk orientation of the farmers as the determinants of their problem confrontation. In order to minimize the extent of the problems, relatively older farmers need to be trained on sunflower cultivation. They need to be prepared to take to some extent of potential challenge of sunflower cultivation through providing input and marketing support by public and private initiatives. -

NATION WIDE PUBLIC WATER POINT MAPPING | a Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE)

NATION WIDE PUBLIC WATER POINT MAPPING | a Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) DPHE Bhaban, 14, Shaheed Captain Monsur Ali Sarani Kakrail, Dhaka-1000, Bangladesh Telephone: + 88-02-9343358 Fax: + 88-02-9343375 www.dphe.gov.bd ISBN: Graphic Design: Expressions ltd. FOREWORD DPHE has been working for supplying safe drinking water and provision of sanitation facilities to the people of Bangladesh since 1926. Since then DPHE has been striving hard to ensure safe potable drinking water for all with the assistance of other development partners of the sector. After detection of Arsenic in ground water in 1993, new challenge emerged in drinking water supply sector. DPHE is still working hard to mitigate arsenic problems from ground water through providing safe water to the people of Bangladesh. During implementation of GOB-UNICEF project, DPHE initiated unique coding system for water points installed under the project to introduce better water point management in the sector. As a follow up of the said initiative, with the financial support from UNICEF, DPHE conducted a survey to gather information on water quality and status of water points installed during 2006 to 2012 under different DPHE projects. The data collected under the survey, thereby analyzed and a report prepared with the technical assistance of the Department of Geology, University of Dhaka. The output based on the present status of water points presented in district wise maps. These will help DPHE and other sector partners to understand the performance and status of functioning of different water supply options and for effective project planning & monitoring. It is highly appreciated for timely initiatives taken from DPHE Planning Circle, Ground Water Circle, Feasibility Study & Design Circle and MIS Unit of DPHE for their mutual cooperation and successfully completion of the program. -

List of Upazilas of Bangladesh

List Of Upazilas of Bangladesh : Division District Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Akkelpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Joypurhat Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Kalai Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Khetlal Upazila Rajshahi Division Joypurhat District Panchbibi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Adamdighi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Bogra Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhunat Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Dhupchanchia Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Gabtali Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Kahaloo Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Nandigram Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sariakandi Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shajahanpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sherpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Shibganj Upazila Rajshahi Division Bogra District Sonatola Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Atrai Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Badalgachhi Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Manda Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Dhamoirhat Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Mohadevpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Naogaon Sadar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Niamatpur Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Patnitala Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Porsha Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Raninagar Upazila Rajshahi Division Naogaon District Sapahar Upazila Rajshahi Division Natore District Bagatipara -

Inventory of LGED Road Network, March 2005, Bangladesh

The Chief Engineer Local Government Engineering Department PREFACE It is a matter of satisfaction that LGED Road Database has been published through compilation of data that represent all relevant information of rural road network of the country in a structured manner. The Rural Infrastructure Maintenance Management Unit of LGED (former Rural Infrastructure Maintenance Cell) took up the initiative to create a road inventory database in mid nineties to register all of its road assets country-wide with the help of customized software called, Road and Structure Database Management System. The said database was designed to accommodate all relevant information on the road network sequentially and the system was upgraded from time to time to cater the growing needs. In general, the purpose of this database is to use it in planning and management of LGED's rural road network by providing detailed information on roads and structures. In particular, from maintenance point of view this helps to draw up comprehensive maintenance program including rational allocation of fund based on various parameters and physical condition of the road network. According to recent road re-classification, LGED is responsible for construction, development and maintenance of three classes of roads, which has been named as Upazila Road, Union Road and Village Road (category A & B) in association with Local Government Institution. The basic information about these roads like, road name, road type, length, surface type, condition, structure number with span, existing gaps with length, etc. has been made available in the road inventory. Side by side, corresponding spatial data are also provided in the road map comprising this document. -

List of School

List of School Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Thana AMTALI Sl Eiin Name Village/Road Mobile 1 100003 DAKSHIN KATHALIA TAZEM ALI SECONDARY SCHOOL KATHALIA 01720343613 2 100009 LOCHA JUUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL LOCHA 01553487462 3 100011 AMTALI A.K. PILOT HIGH SCHOOL 437, A K SCHOOL ROAD, 01716296310 AMTALI 4 100012 CHOTONILGONG HIGH SCHOOL CHOTONILGONG 01718925197 5 100014 SHAKHRIA HIGH SCHOOL SHAKHARIA 01712040882 6 100015 GULSHA KHALIISHAQUE HIGH SCHOOL GULISHAKHALI 01716080742 7 100016 CHARAKGACHIA SECONDARY SCHOOL CHARAKGACHIA 01734083480 8 100017 EAST CHILA RAHMANIA HIGH SCHOOL PURBA CHILA 01716203073,0119027693 5 9 100018 TARIKATA SECONDARY SCHOOL TARIKATA 01714588243 10 100019 CHILA HASHEM BISWAS HIGH SCHOOL CHILA 01715952046 11 100020 CHALAVANGA HIGH SCHOOL PRO CHALAVANGA 01726175459 12 100021 CHUNAKHALI HIGH SCHOOL CHUNAKHALI 01716030833 13 100022 MAFIZ UDDIN GIRLS PILOT HIGH SCHOOL UPZILA ROAD 01718101316 14 100023 GOZ-KHALI(MLT) HIGH SCHOOL GOZKHALI 01720485877 15 100024 KAUNIA IBRAHIM ACADEMY KAUNIA 01721810903 16 100026 ARPAN GASHIA HIGH SCHOOL ARPAN GASHIA 01724183205 17 100028 SHAHEED SOHRAWARDI SECONDARY SCHOOL KUKUA 01719765468 18 100029 KALIBARI JR GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KALIBARI 0172784950 19 100030 HALDIA GRUDAL BANGO BANDU HIGH SCHOOL HALDIA 01715886917 20 100031 KUKUA ADARSHA HIGH SCHOOL KUKUA 01713647486 21 100032 GAZIPUR BANDAIR HIGH SCHOOL GAZIPUR BANDAIR 01712659808 22 100033 SOUTH RAOGHA NUR AL AMIN Secondary SCHOOL SOUTH RAOGHA 01719938577 23 100034 KHEKUANI HIGH SCHOOL KHEKUANI 01737227025 24 100035 KEWABUNIA SECONDARY -

Phone No. Upazila Health Center

District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Bagerhat Chitalmari Chitalmari Upazila Health Complex 01730324570 Bagerhat Fakirhat Fakirhat Upazila Health Complex 01730324571 Bagerhat Kachua Kachua Upazila Health Complex 01730324572 Bagerhat Mollarhat Mollarhat Upazila Health Complex 01730324573 Bagerhat Mongla Mongla Upazila Health Complex 01730324574 Bagerhat Morelganj Morelganj Upazila Health Complex 01730324575 Bagerhat Rampal Rampal Upazila Health Complex 01730324576 Bagerhat Sarankhola Sarankhola Upazila Health Complex 01730324577 Bagerhat District Sadar District Hospital 01730324793 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Bandarban Alikadam Alikadam Upazila Health Complex 01730324824 Bandarban Lama Lama Upazila Health Complex 01730324825 Bandarban Nykongchari Nykongchari Upazila Health Complex 01730324826 Bandarban Rowangchari Rowangchari Upazila Health Complex 01811444605 Bandarban Ruma Ruma Upazila Health Complex 01730324828 Bandarban Thanchi Thanchi Upazila Health Complex 01552140401 Bandarban District Sadar District Hospital, Bandarban 01730324765 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Barguna Bamna Bamna Upazila Health Complex 01730324405 Barguna Betagi Betagi Upazila Health Complex 01730324406 Barguna Pathargatha Pathargatha Upazila Health Complex 01730324407 Barguna Amtali Amtali Upazila Health Complex 01730324759 Barguna District Sadar District Hospital 01730324884 District Upazila Name of Hospitals Mobile No. Barisal Agailjhara Agailjhara Upazila Health Complex 01730324408 Barisal Babuganj Babuganj Upazila Health -

15-JUL-20 Page 1 Source:BANBEIS BARISAL Division BARGUNA

15-JUL-20 LIST OF EBTEDYAEE MADRASAH Division BARISAL District BARGUNA Upazila AMTALI Slno Name of Madrasah 1 ALDE AZEZEA EBTEDAY MADRASAH 2 ALGI AZIZA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 3 AMRAGACHHIA MADINATUL ULUM HOSAINIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 4 ATHARAGACHHIA BASERIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 5 CHALAVANGA SHATANTRO EBTADAYEE MADRASHA 6 CHARKHALI SATANTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 7 CHAWRA CHALITA BUNIA ADORSHO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 8 CHAWRA HASANIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 9 CHOTO NILGANJ NECHARIA SWATANTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 10 CHOTO NILGONG NESARIA SHATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 11 CHURA BATMOR A.K. EBTADIAY MADRASHA 12 DAKHIN PASCHIM AMTALI LOSA INDEPENDENT EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 13 DAKSHIN DALACHARA HAMIDIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 14 DAKSHIN RAOKHA MOHAMMADIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 15 DALACHARA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 16 DASHIN RAUGA MAGFURIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 17 EAST SHAKHARIA MESERIA SATONTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 18 GAZIPUR DUARIPARA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 19 GHOTKHALI SHATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 20 GOGKAHALI TASAUF SATANTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 21 GOGKHALI AMENIA EBTEDEAYEE MADRASHA 22 GOSKALI SOLIMABAD MAZAR SORIF SOLIMIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 23 HAT-CHUNAKHALI SATANTRO EBTADAI MADRASHA 24 KARIBOUNIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 25 KEWABUNIA AYNALIA SWATANTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 26 KHAKUANAI SHAWTANTRA EBTADAYEE MADRASHA 27 KHEKUANIA SATANTRO EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 28 KULAIR CHAR SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 29 KUTUBPUR ESRAILIA SATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASAH 30 MADDA GOJKHALI SHATANTRA EBTEDAYEE MADRASHA 31 MADDHYA -

জেলা পরিসংখ্যান ২০১১ District Statistics 2011 Pirojpur

জেলা পরিসংখ্যান ২০১১ District Statistics 2011 Pirojpur December 2013 BANGLADESH BUREAU OF STATISTICS (BBS) STATISTICS AND INFORMATICS DIVISION (SID) MINISTRY OF PLANNING GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF BANGLADESH District Statistics 2011 Pirojpur District District Statistics 2011 Published in December, 2013 Published by : Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Printed at : Reproduction, Documentation and Publication (RDP) Section, FA & MIS, BBS Cover Design: Chitta Ranjon Ghosh, RDP, BBS ISBN: For further information, please contact: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) Statistics and Informatics Division (SID) Ministry of Planning Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Parishankhan Bhaban E-27/A, Agargaon, Dhaka-1207. www.bbs.gov.bd COMPLIMENTARY This book or any portion thereof cannot be copied, microfilmed or reproduced for any commercial purpose. Data therein can, however, be used and published with acknowledgement of the sources. ii District Statistics 2011 Pirojpur District Foreword I am delighted to learn that Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) has successfully completed the ‘District Statistics 2011’ under Medium-Term Budget Framework (MTBF). The initiative of publishing ‘District Statistics 2011’ has been undertaken considering the importance of district and upazila level data in the process of determining policy, strategy and decision-making. The basic aim of the activity is to publish the various priority statistical information and data relating to all the districts of Bangladesh. The data are collected from various upazilas belonging to a particular district. The Government has been preparing and implementing various short, medium and long term plans and programs of development in all sectors of the country in order to realize the goals of Vision 2021.