Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arcelormittal Is Again Counting on the Strengths of the AUMUND Drag Chain Conveyor Type LOUISE São Paulo, Brazil, April 2017

Press Information ArcelorMittal is again counting on the strengths of the AUMUND Drag Chain Conveyor Type LOUISE São Paulo, Brazil, April 2017 The steel maker ArcelorMittal is building on proven solutions and reliable partners in Brazil. About 20 years ago, a shock-pressure-proof drag chain conveyor was ordered for Brazil from LOUISE Fördertechnik before this company was acquired by AUMUND Fördertechnik GmbH, and now AUMUND has won an order for another drag chain conveyor type LOUISE TKF. The shock-pressure-proof design of its predecessor was no longer required for the new model because of the change in classification of the plant segment. The dispatch of the machine is planned for June 2017. 1998: AUMUND Drag Chain Conveyor, type LOUISE TKF, in ArcelorMittal’s João Monlevade plant in Brazil (photo AUMUND) The earlier model drag chain conveyor was ordered in 1998 by the then Brazilian arm of the Luxemburg steel company Arbed, CSBM, Companhia Siderurgica Belgo Mineira. Arcelor was created by the merger of Aceralia and Usinor and merged with Mittal in 2006 to become ArcelorMittal, the world’s leading steel concern. Press Information Around fifteen years ago, AUMUND Fördertechnik GmbH integrated the products of the LOUISE subsidiary into its own portfolio. This double strand drag chain conveyor with a capacity of 3 kW, a centre distance of 10.4 m and a performance of 25 t/h, will be used for bunker extraction. The previous machine proved its durability in an interesting way. One of the supports of a weighing cell collapsed and caused one side of the silo to subside. -

The Modern Brazilian Steel Industry

THE MODERN BRAZILIAN STEEL INDUSTRY By Professor Celso Lafer* *Minister of Foreign Relations Notwithstanding the importance of pioneer initiatives by the first generation of Brazilian industrialists, the foundation and growth of the modern steel industry in Brazil was made, in great part, by the state. Steel symbolized industrialization which, for many decades, was synonymous with progress. The government realized, correctly, that having vast reserves of iron ore, Brazil could aspire to a significant steel industry. And it acted on this belief, creating the industry during the Getúlio Vargas administration and promoting its growth during the decades of 1960 and 1970. The predominantly state model that was necessary at the industry’s inception had some success cases. Without the government’s action in the 1930s and 1940s, Brazil would probably not have developed a robust steel-producing base. During the following decades Brazil positioned itself among the main producers and exporters of steel in the world. The state model came to an end, as happened in other sectors, when the government management crisis brought to the surface unsustainable inefficiencies and weaknesses of the productive segment. During the 1990s the steel sector experienced a great transformation. In three years, between 1991 and 1993, all of the state steel industry was privatized through public bidding, and massive investment began to modernize it. In 1998 alone more funds were invested than the sum of monies invested during the 5-year period 1989-1994. In total, between 1994 and 2000, the new steel mill owners invested US$ 10.2 billion in modernization, upgrading, cost reduction and environmental protection works. -

Core Strengths, Sustainable Returns

Core strengths, sustainable returns Annual Report 2011 With revenues of $94 billion and crude steel production of 91.9 million tonnes, ArcelorMittal is the world’s leading steel and mining company, with a presence in more than 60 countries. Through our core values of sustainability, quality and leadership, we commit to operating in a responsible way with respect to the health, safety and well-being of our employees, contractors and the communities in which we operate. The theme for this year’s annual report is ‘core strengths, sustainable returns’. We believe consistency is crucial in a fast-changing world. And at the heart of this belief is a consistent strategy that focuses on our five core strengths. By continually focusing on these strengths throughout our operations, ArcelorMittal can deliver sustainable returns. Cover image Port-Cartier, Canada Global presence ArcelorMittal is the world’s leading steel and mining company. With a presence in more than 60 countries, we operate a balanced portfolio of cost competitive steel plants across both the developed and developing world. We are the leader in all the main sectors – automotive, household appliances, packaging and construction. We are also the world’s fourth largest producer of iron ore, with a global portfolio of 16 operating units with mines in operation or development. In 2011, we employed around 261,000 people. Flat Carbon Long Carbon Belgium France Mexico US Algeria Germany Charleroi Basse Indre Lázaro Cárdenas Burns Harbor, IN Annaba Duisburg Ghent Châteauneuf Cleveland, OH -

Case No COMP/M.3334 ΠARCELOR/ THYSSENKRUPP/ STEEL24-7

Case No COMP/M.3334 – ARCELOR/ THYSSENKRUPP/ STEEL24-7 Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 16/02/2004 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 304M3334 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 16.02.2004 SG-Greffe(2004) D/200619/200620 In the published version of this decision, PUBLIC VERSION some information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and MERGER PROCEDURE other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where ARTICLE 6(1)(b) DECISION possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. To the notifying parties : Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.3334 Arcelor/Thyssenkrupp/Steel 24-7 Notification of 14 January 2004 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No 4064/89 1. On January 14, 2004, the Commission received a notification pursuant to Article 4 of Regulation (EEC) No 4064/891 as last amended by Regulation (EC) No 1310/972 (“the Merger Regulation”) of a proposed concentration by which ThyssenKrupp AG (“ThyssenKrupp”) acquires an additional 25% of the share capital in the existing Joint Venture Steel 24-7. After completion of the transaction, ThyssenKrupp and Arcelor SA (“Arcelor”) will each own 50% of the shares in Steel 24-7. The companies will have joint control over Steel 24-7 within the meaning of Article 3(1) (b) of the Merger Regulation. -

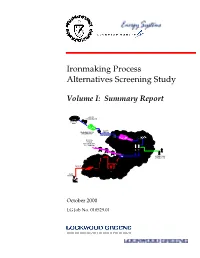

Ironmaking Process Alternatives Screening Study, Volume I

Ironmaking Process Alternatives Screening Study Volume I: Summary Report ORE TO CONCENTRATOR IRON ORE MINE SLURRY ORE BENEFICIATION PIPELINE CONCENTRATOR CONCENTRATE SLURRY ELECTRIC PELLET RECEIVING, PELLET POWER STOCKPILE DEWATERING PLANT (50% FROM COAL, 50% FROM N.G.) DIRECT REDUCTION PLANTS NATURAL GAS EAF MELTING NATURAL GAS DRI PRODUCTION STEEL TO PORT SLABS SLAB LMFs CASTER SLAB VACUUM SHIPPING DEGASSING October 2000 LG Job No. 010529.01 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. Contents Volume I: Ironmaking Alternative Study Executive Summary...............................................................................1 Study Scope and Methodology............................................................2 -

“Social Aspects and Financing of Industrial Restructuring”

INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANIZATION UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE REGIONAL FORUM “Social Aspects and Financing of Industrial Restructuring” 26 and 27 November 2003, Moscow, Russian Federation Topic 2. Social costs of restructuring and their financing: a closer view Restructuring in the Industry of Luxembourg. Major Issues, Actors and Lessons to Learn By Mr. Albert ZENNER – Director Human Resources, Arbed – Arcelor Group Luxembourg (This paper is being circulated by the secretariat as received from the author) UNITED NATIONS Page 1 sur 13 Restructuring in the Industry of Luxembourg Major issues, Actors and Lessons to learn By Albert ZENNER, Director Human Resources, Arbed – Arcelor Group. Luxembourg might be known by many of You as a banking centre or a country hosting European institutions, and some of You will even know that it is the Headquarters of ARCELOR, the world’s largest steel producer, created by the merger of three companies: the French USINOR, the Spanish ACERALIA, and ARBED, the steel company of LUXEMBOURG. All this is true, but LUXEMBOURG is also an independent country, which has undergone deep changes during the last three decades. These changes result from the restructuring of the steel industry, which for more than a century has been the pillar of the Luxembourg economy. During my presentation I will speak about the major issues of this restructuring, the key players, and the lessons to learn from our point of view. I will also try to show how some of the lessons are applied now within the new group ARCELOR. GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND POPULATION. For locating Luxembourg geographically we have to zoom the map of Western Europe. -

Studies in Global Social History

Fabricating Modern Societies <UN> Studies in Global Social History Series Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, AZ, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, NY, usa) volume 37 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> Fabricating Modern Societies Education, Bodies, and Minds in the Age of Steel Edited by Karin Priem and Frederik Herman leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Apprentices with a telescope at the seaside in Belgium. Undated. Digital positive from glass plate negative. © Institut Emile Metz. cna Collection (HISACS000048V01). The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov lc record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2019023135 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1874-6705 isbn 978-90-04-34423-5 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-41051-0 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by the Authors. Published by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. -

Informe Del Servicio De Defensa De La Competencia

SECRETARÍA DE ESTADO DE ECONOMÍA MINISTERIO DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE DEFENSA DE ECONOMÍA DE LA COMPETENCIA INFORME DEL SERVICIO DE DEFENSA DE LA COMPETENCIA N-03019 ARCELOR / DUFERDOFIN Con fecha 9 de mayo de 2003 ha tenido entrada en este Servicio de Defensa de la Competencia notificación relativa a la adquisición por parte de la empresa ARCELOR del control exclusivo sobre la empresa de nueva creación PALLANZENO NEWCO perteneciente a la empresa DUFERDOFIN SpA, del Grupo DUFERCO. Dicha notificación ha sido realizada por ARCELOR según lo establecido en el artículo 15.1 de la Ley 16/1989, de 17 de julio, de Defensa de la Competencia por superar el umbral establecido en el artículo 14.1 a). A esta operación le es de aplicación lo previsto en el Real Decreto 1443/2001, de 21 de diciembre, por el que se desarrolla la Ley 16/1989, en lo referente al control de las concentraciones económicas. El artículo 15 bis de la Ley 16/1989 establece que: "El Ministro de Economía, a propuesta del Servicio de Defensa de la Competencia, remitirá al Tribunal de Defensa de la Competencia los expedientes de aquellos proyectos u operaciones de concentración notificados por los interesados que considere pueden obstaculizar el mantenimiento de una competencia efectiva en el mercado, para que aquél, previa audiencia, en su caso, de los interesados dictamine al respecto". Asimismo, se añade: "Se entenderá que la Administración no se opone a la operación si transcurrido un mes desde la notificación al Servicio, no se hubiera remitido la misma al Tribunal". De acuerdo con lo estipulado en el artículo 15.2 de la Ley 16/1989, la notificante solicita que, en el caso de que el Ministro de Economía resuelva remitir el expediente al Tribunal de Defensa de la Competencia, se levante la suspensión de la ejecución de la operación. -

SA in Kraków, Poland—Basic Oxygen Furnace Steel Production

Int J Life Cycle Assess (2012) 17:463–470 DOI 10.1007/s11367-011-0370-y LCI METHODOLOGY AND DATABASES Life cycle inventory processes of the ArcelorMittal Poland (AMP) S.A. in Kraków, Poland—basic oxygen furnace steel production A case study Boguslaw Bieda Received: 8 September 2011 /Accepted: 12 December 2011 /Published online: 11 January 2012 # The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract parameters as well as air emissions associated with the BOF Purpose The goal of this paper is to describe the life cycle steelmaking process were presented. The production data inventory (LCI) approach to steel produced by ArcelorMit- (steel) was given. The emissions of SO2,NO2, CO, CH4, ’ tal s Basic Oxygen Furnace (AMBOF) in Kraków, Poland. CO2, dust, heavy metals (Cr, Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni and Mn) and The present LCI is representative for the reference year waste (slag and gas cleaning sludge) are the most important 2005 by application of PN-EN ISO 14040:2009 (PN-EN outcomes of the steel process. ISO 2009). The system boundaries were labeled as gate-to- Results With regard to 1,677,987 Mg of steel produced by gate (covering a full chain process of steel production). The AMBOF, the consumption of natural gas, blast furnace gas background input and output data from the basic oxygen and coke oven gas amounted to 10,671,997, 755,094 and furnace (BOF) steelmaking process has been inventoried as 13,222,537.6 m3/year, respectively. Electric energy, steam, follows: pig iron, scrap, slag forming materials (CaO), fer- air, oxygen and heat input amounts were in the order of roalloys, Al, carbon and graphite carburizer (material for 45,003,611.3 kWh, 21,646.03 Mg, 107,592,526 m3, carburization of steel), isolating powder, consumption of 90,611,298 m3 and 16,779.87 GJ, respectively. -

BAT Guide for Electric Arc Furnace Iron & Steel Installations

Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı BAT Guide for electric arc furnace iron & steel installations Project TR-2008-IB-EN-03 Mission no: 2.1.4.c.3 Prepared by: Jesús Ángel Ocio Hipólito Bilbao José Luis Gayo Nikolás García Cesar Seoánez Iron & Steel Producers Association Serhat Karadayı (Asil Çelik Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş.) Muzaffer Demir Mehmet Yayla Yavuz Yücekutlu Dinçer Karadavut Betül Keskin Çatal Zerrin Leblebici Ece Tok Şaziye Savaş Özlem Gülay Önder Gürpınar October 2012 1 Eşleştirme Projesi TR 08 IB EN 03 IPPC – Entegre Kirlilik Önleme ve Kontrol T.C. Çevre ve Şehircilik Bakanlığı Contents 0 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................ 12 1 INTRODUCTION. ..................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE DIRECTIVE ON INDUSTRIAL EMISSIONS IN THE SECTOR OF STEEL PRODUCTION IN ELECTRIC ARC FURNACE ................................................................................. 14 1.2 OVERVIEW OF THE SITUATION OF THE SECTOR IN TURKEY ...................................................... 14 1.2.1 Current Situation ............................................................................................................ 14 1.2.2 Iron and Steel Production Processes............................................................................... 17 1.2.3 The Role Of Steel Sector in -

Trend of Ironmaking Technology in Japan After 2000

NIPPON STEEL TECHNICAL REPORT No. 123 MARCH 2020 Technical Review UDC 669 . 162 : 622 . 785 /. 788 Trend of Ironmaking Technology in Japan after 2000 Seiji NOMURA* Abstract The first two decades of the 21st century were turbulent for the steel industry. The reor- ganization of the steel industry across borders has progressed and the increased demand for steel products has caused a rise in the price of raw materials such as iron ore and metal- lurgical coal. Furthermore, more emphasis has been placed on global environmental pro- tection and carbon dioxide emission control than ever before. The ironmaking technology division in Japan has struggled to cope with these changes both at home and abroad. This report describes the trend of the development and commercial application of the ironmaking technology of Japan in the first two decades of the 21st century. 1. Introduction—Situation of Japan’s Ironmaking ply of high-quality iron ore and coking coal was suddenly consid- after 2000 ered as a bottleneck, and their market prices became highly volatile Soon after the rapid valuation of the Japanese yen brought about over the last few years depending on the supply-demand balance by the Plaza Accord in 1985, the blast furnace operators of Japan (see Fig. 1). 1) took business streamlining measures and eliminated their blast fur- In contrast, the production amounts of pig iron and crude steel of naces one after another. Then in the 1990s, the Japanese steel indus- Japan have remained substantially unchanged over the last 20 years try was forced into tough times facing sluggish demand resulting except for a temporary and significant slump in the aftermath of from the breakdown of the bubble economy and further valuation of Lehman’s fall, and owing to stagnant domestic steel consumption, the currency. -

City Promenade

CITY PROMENADE LUXEMBOURG-CENTRE, OLD TOWN, FORTRESS WALLS AND BEST VIEWS 19 HISTORIC SURVEY In 963, the Count Siegfried of the Ardennes built his forti- fied castle on the Bock promontory, and it became the cradle of the city of Luxembourg. The first markets were held in front of Saint Michael’s Church, surrounded by a simple fortification. Across the centuries, a second and then a third wall were erected on the Western side, while the rocks of the Alzette and Pétrusse valleys served as a natural defence. Never- theless, these strong fortified structures did not prevent Burgundians from taking over the city in 1443, a city which beyond any doubt was to own a major strategic position on the European chessboard. For over four centuries, the best military engineers from Burgundy, Spain, France, Austria and the German Con- federation ended up turning it into one of the most forti- fied places on earth, the so-called “Gibraltar of the North”. The strength of its defence stemmed from its three forti- fied belts, the first of which was composed of bastions, the second of 15 forts and the third, being the outside wall, was composed of 9 forts, all of which were carved into the rock. An extraordinary 14.2 mile-network of underground galleries – the famous Casemates – and more than 1 2 3 4 5 7 40,000 square meters of bomb-shelters were lodged in the city’s rocks. They could shelter not only thousands of defenders, including their horses and equipment, but also artillery and weapon workshops, kitchens, bakeries, slaughterhouses, and so forth.