Hamas and Yahya Sinwar's Tough Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamas's Fight Against COVID-19 in the Gaza Strip (Updated to April 5, 2020)

רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר רמה כ ז מל ו תשר מה ו ד י ע י ן ( למ מ" ) כרמ ז מה י עד מל ו ד י ע י ן ול רט ו ר Hamas’s fight against COVID-19 in the Gaza Strip (updated to April 5, 2020) April 5, 2020 Morbidity On March 31, 2020, two new COVID-19 cases were identified among people returning from Egypt to the Gaza Strip through the Rafah crossing. They were quarantined. This brings the number of patients in the Gaza Strip to 12. According to the spokesman for the Health Ministry in the Gaza Strip, five patients have already recovered and the condition of the rest is “stable and encouraging” (Al-Ra’i News Agency, April 4, 2020). According to the spokesman for the Health Ministry in the Gaza Strip, Dr. Ashraf al-Qidra, there are now 1,897 people in 27 quarantine centers. They are all in good health and are soon to be released. The schools serving as quarantine centers will be disinfected 24 hours after they are discharged, so that the facilities can be reused (Al-Ra’i News Agency, April 4, 2020). -

The Virus of Hate: Delegitimization and Antisemitism Converge Around

Ministry of Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy The Virus of Hate Delegitimization and Antisemitism Converge Around the Coronavirus May 2020 Main Findings In September 2019, the Ministry of Strategic Affairs published a report, "Behind the Mask," which demonstrated the connection between antisemitism and the Boycott Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement and its delegitimacy campaign against the State of Israel. The report included over 80 examples of leading BDS activists disseminating antisemitic content, consistent with the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism. Following the report, and in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, the Ministry has been monitoring antisemitism and efforts to delegitimize Israel with the linking of the State of Israel and Jews to the coronavirus. The Ministry and other organizations focused on combatting hate speech found multiple cases of BDS-supporting organizations and senior government and quasi-governmental officials propagating antisemitic conspiracies and libels. The increased antisemitic rhetoric around the coronavirus has also been accompanied by threats of violence against Jews and Israelis. In the US, the FBI warned that right wing extremists may try to infect Jews with the coronavirus; in Gaza, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar warned that if Gaza were to lack ventilators, "six million Israelis will not breathe." Such threats may materialize into acts of violence, especially as stay home orders are lifted and right wing extremists then may vent their anger -

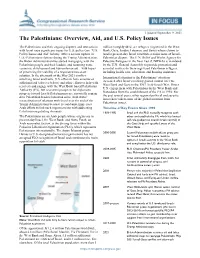

The Palestinians: Overview, 2021 Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues

Updated September 9, 2021 The Palestinians: Overview, Aid, and U.S. Policy Issues The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions million (roughly 44%) are refugees (registered in the West with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “U.S. Bank, Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria) whose claims to Policy Issues and Aid” below). After a serious rupture in land in present-day Israel constitute a major issue of Israeli- U.S.-Palestinian relations during the Trump Administration, Palestinian dispute. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for the Biden Administration has started reengaging with the Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is mandated Palestinian people and their leaders, and resuming some by the U.N. General Assembly to provide protection and economic development and humanitarian aid—with hopes essential services to these registered Palestinian refugees, of preserving the viability of a negotiated two-state including health care, education, and housing assistance. solution. In the aftermath of the May 2021 conflict International attention to the Palestinians’ situation involving Israel and Gaza, U.S. officials have announced additional aid (also see below) and other efforts to help with increased after Israel’s military gained control over the West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct recovery and engage with the West Bank-based Palestinian U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and Authority (PA), but near-term prospects for diplomatic progress toward Israeli-Palestinian peace reportedly remain Gaza dates from the establishment of the PA in 1994. For the past several years, other regional political and security dim. -

INSS Insight No. 1309, April 27, 2020 Israel and Hamas: from Corona to Prisoners and a Possible Arrangement

INSS Insight No. 1309, April 27, 2020 Israel and Hamas: From Corona to Prisoners and a Possible Arrangement Yohanan Tzoreff and Kobi Michael Out of fears of a COVID-19 outbreak in Gaza as well as a desire to strengthen public trust in the organization and demonstrate its control over the situation, Yahya Sinwar, the leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip, has proposed an initiative to release prisoners. The initiative led to indirect talks between Israel and Hamas, which may foster a wider arrangement. Israel should not make concessions solely for information on its citizens and the bodies of its soldiers being held in Gaza, but strive to bring them back while also working to bring about a better security reality for after the coronavirus crisis. On April 2, 2020, Yahya Sinwar, the head of the Hamas political bureau in the Gaza Strip, was interviewed on the Hamas-controlled al-Aqsa TV channel. During the interview Sinwar sought to dispel public fears about COVID-19, make it clear that Hamas is managing the situation effectively, and strengthen public trust in the organization's leadership. Sinwar also directed a message at Israel regarding a possible deal for releasing prisoners. He insisted that there has been no change in the official Hamas stance demanding the release from Israeli prisons of its operatives who were freed as part of the Shalit deal and rearrested during Operations Brother's Keeper and Protective Edge of 2014. He also stated that the leadership vacuum in Israel over the last year has prevented progress on this issue. -

Submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence And

Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council Submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security on its Review of the re-listing of al-Shabaab, Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas Brigades), the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT) and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code. Introduction This document forms the submission by the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council (AIJAC) to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security (PJCIS) on its review into the relisting of al-Shabaab, Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades (Hamas Brigades), the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), Lashkar-e-Tayyiba (LeT) and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code 1995. This submission will focus on the relisting of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, though AIJAC also strongly supports the relisting of Palestinian Islamic Jihad: It recommends that the PJCIS not disallow the listing of the Hamas Brigades. It also recommends that the PJCIS advise the Minister for Home Affairs to extend the listing of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades to Hamas in its entirety. There are three reasons why AIJAC makes these recommendations: 1. There is compelling and publicly available evidence to suggest all of Hamas, not just the Hamas Brigades, is engaged in activity that meets ASIO’s criteria for selecting an organisation to be listed under the Criminal Code 1995. 2. Last year, Yahya Sinwar, a long-time leader of the Hamas Brigades, was nominated Hamas leader in Gaza. This nomination provides recent and compelling evidence that there is no separation between Hamas and the Hamas Brigades. -

Palestinian Reconciliation and the Potential of Transitional Justice

Brookings Doha Center Analysis Paper Number 25, March 2019 Palestinian Reconciliation and the Potential of Transitional Justice Mia Swart PALESTINIAN RECONCILIATION AND THE POTENTIAL OF TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE Mia Swart The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2019 Brookings Institution THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 III. Background on the Rift Between Fatah and Hamas ...............................................7 IV. The Concept -

Zionist Federation of Australia Submission to the Parliamentary Joint

306 Hawthorn Road 3/146 Darlinghurst Road Caulfield South, VIC 3162 Darlinghurst, NSW 2010 +613 9272 5644 +612 9360 9938 [email protected] [email protected] www.zfa.com.au www.zfa.com.au Zionist Federation of Australia submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security review of five organisations as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code Jeremy Leibler, President, Zionist Federation of Australia Dr Bren Carlill, Director of Public Affairs, Zionist Federation of Australia Contents • Recommendations • Hamas’s Brigades continue to meet the definition of a terrorist organisation • Internal inconsistencies in the Australian Government’s proscription of the Brigades • Parallels with Islamic State • Hamas political leadership preparing, planning, assisting, fostering and advocating the doing of terrorist acts • Statements by members of Hamas politburo o Advocating terrorist acts o Indicating that the politburo directs the Brigades’ activities o Indicating that Hamas has no intention of changing its tactics • Cultivating children • Hamas-owned media advocate terrorism Recommendations Recommendation 1 The ZFA recommends that the PJCIS not disallow Criminal Code (Terrorist Organisation—Hamas’ Izz al‑Din al‑Qassam Brigades) Regulations 2021. Recommendation 2 The ZFA recommends that the PJCIS urge the Minister to proscribe the entire organisation of Hamas. REPRESENTATION. ADVOCACY. CONNECTION. President Jeremy Leibler Chief Executive Officer Ginette Searle Constituent Organisations State Zionist Councils of: ACT -

The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S

Updated April 14, 2020 The Palestinians: Overview and Key Issues for U.S. Policy The Palestinians and their ongoing disputes and interactions health care, education, and housing assistance to Palestinian with Israel raise significant issues for U.S. policy (see “Key refugees. U.S. Policy Issues” below). U.S.-Palestinian tensions have risen in connection with Trump Administration actions International attention to the Palestinians’ situation increased after Israel’s military gained control over the generally seen as favoring Israel, including the release of a U.S. peace plan in January 2020. Within a complicated West Bank and Gaza in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. Direct legal and political context, the United States suspended U.S. engagement with Palestinians in the West Bank and bilateral aid to the Palestinians in 2019. The resumption of Gaza dates from the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in 1994. For the past several years, other aid may depend on various factors mentioned below, including the public health and economic effects of the regional political and security issues have taken some of the global COVID-19 pandemic. The virus’s potential impact global attention from Palestinian issues. on the Gaza Strip—given its infrastructure problems and Timeline of Key Events Since 1993 high population density—may be of particular concern, 1993-1995 Israel and the PLO mutually recognize each with possible ripple effects for Israel. other and establish the PA, which has limited The Palestinians are an Arab people whose origins are in self-rule (subject to overall Israeli control) in present-day Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Updated March 18, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL34074 SUMMARY RL34074 The Palestinians: March 18, 2021 Background and U.S. Relations Jim Zanotti The Palestinians are an Arab people whose origins are in present-day Israel, the West Specialist in Middle Bank, and the Gaza Strip. Congress pays close attention—through legislation and Eastern Affairs oversight—to the ongoing conflict between the Palestinians and Israel. The current structure of Palestinian governing entities dates to 1994. In that year, Israel agreed with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) to permit a Palestinian Authority (PA) to exercise limited rule over Gaza and specified areas of the West Bank, subject to overarching Israeli military administration that dates back to the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. After the PA’s establishment, U.S. policy toward the Palestinians focused on encouraging a peaceful resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, countering Palestinian terrorist groups, and aiding Palestinian goals on governance and economic development. Since then, Congress has appropriated more than $5 billion in bilateral aid to the Palestinians, who rely heavily on external donor assistance. Conducting relations with the Palestinians has presented challenges for several Administrations and Congresses. The United States has historically sought to bolster PLO Chairman and PA President Mahmoud Abbas vis-à-vis Hamas (a U.S.-designated terrorist organization supported in part by Iran). Since 2007, Hamas has had de facto control within Gaza, making the security, political, and humanitarian situation there particularly fraught. The Abbas-led PA still exercises limited self-rule over specified areas of the West Bank. -

Review of the Re-Listing of Five Organisations As Terrorist Organisations Under the Criminal Code

SUBMISSION: FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security Review of the re-listing of five organisations as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code JONATHAN SCHANZER Senior Vice President for Research Foundation for Defense of Democracies Washington, DC August 20, 2021 www.fdd.org Submission to the Review of the re-listing of five organisations as terrorist organisations under the Criminal Code Dr. Jonathan Schanzer Senior Vice President for Research, Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) Contents Recommendations Introduction Re-listing Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades The Case for an Expanded Listing Recommendations Recommendation 1: I strongly recommend that the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security support the re-listing of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades under the Criminal Code and not disallow the legislative instrument. Recommendation 2: I strongly recommend that the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security urge the Minister for Home Affairs to list the entirety of Hamas as a terrorist organization. Introduction I thank the committee for the opportunity to contribute to its review of the re-listing of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, the so-called “armed wing” of Hamas. I serve as senior vice president for research at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), a Washington, DC-based nonpartisan, non-profit research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy. FDD conducts actionable research intended for consumption by governments, intelligence agencies, the military, the private sector, academia, and journalists. Our work draws upon our skills and experience in foreign languages, economics, law, technology, the military, and more. -

News of Terrorism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

News of Terrorism and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict (February 8 – 14, 2017) Four rockets were fired at the southern Israeli city of Eilat from the Sinai Peninsula this past week. Three were intercepted by the Iron Dome aerial defense system. Left: Claim of responsibility issued by ISIS's Sinai Province (al-Haq, February 9, 2017). Right: The fourth rocket, which fell in an open area near Eilat (Twitter account of Palinfo, February 8, 2017). Overview n Popular terrorism attacks continue in Judea and Samaria and trickle into Israel. Prominent this past week was a combined shooting and stabbing attack at the entrance to a market in Petah Tikva, in the center of the country. Seven people were wounded. The Palestinian terrorist who carried out the attack came from a village south of Nablus. He apparently acted independently. Hamas welcomed the attack; the PA did not condemn it. n Four rockets were fired at Eilat, Israel's southernmost city, from the Sinai Peninsula. They were launched by operatives of ISIS's Sinai Province. Three of the rockets were intercepted by the Iron Dome aerial defense system; the fourth fell in an open area near Eilat. ISIS's Sinai Province claimed responsibility for the attack and threatened "the future will be even worse and more bitter" for the Jews. n In the Gaza Strip Yahya Sinwar, a senior operative in Hamas' Izz al-Din Qassam Brigades, its military-terrorist wing, was elected as the organization's leader in the Gaza Strip (replacing Ismail Haniyeh, a candidate for the position currently held by Khaled Mashaal). -

The Crisis of the Gaza Strip: a Way out Anat Kurz, Udi Dekel, and Benedetta Berti, Editors

The Crisis of the Gaza Strip: A Way Out Anat Kurz, Udi Dekel, and Benedetta Berti, Editors COVER The Crisis of the Gaza Strip: A Way Out Anat Kurz, Udi Dekel, and Benedetta Berti, Editors Institute for National Security Studies The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), incorporating the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies, was founded in 2006. The purpose of the Institute for National Security Studies is first, to conduct basic research that meets the highest academic standards on matters related to Israel’s national security as well as Middle East regional and international security affairs. Second, the Institute aims to contribute to the public debate and governmental deliberation of issues that are – or should be – at the top of Israel’s national security agenda. INSS seeks to address Israeli decision makers and policymakers, the defense establishment, public opinion makers, the academic community in Israel and abroad, and the general public. INSS publishes research that it deems worthy of public attention, while it maintains a strict policy of non-partisanship. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute, its trustees, boards, research staff, or the organizations and individuals that support its research. The Crisis of the Gaza Strip: A Way Out Anat Kurz, Udi Dekel, and Benedetta Berti, Editors משבר רצועת עזה — מענה לאתגר עורכים: ענת קורץ, אודי דקל, בנדטה ברטי Graphic design: Michal Semo-Kovetz, Yael Bieber Cover design: Michal Semo-Kovetz Cover photo: Trucks entering Gaza from Israel at the Kerem Shalom crossing, August 28, 2014.