The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Munich Olympics Gene Eisen Terrorists Strike the 1972 Summer Olympics Held in Munich, West Germany, Were Breezing Along Successfully for the First Ten Days

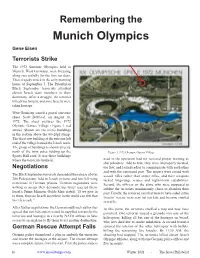

Remembering the Munich Olympics Gene Eisen Terrorists Strike The 1972 Summer Olympics held in Munich, West Germany, were breezing along successfully for the first ten days. Then, tragedy struck in the early morning hours of September 5. The Palestinian Black September terrorists attacked eleven Israeli team members in their dormitory. After a struggle, the terrorist killed two Israelis, and nine Israelis were taken hostage. West Germany issued a postal souvenir sheet, Scott B489a-d, on August 18, 1972. The sheet pictures the 1972 Olympic Games Village (Figure 1 red arrow). Shown are the men’s buildings in the section above the 40+20pf stamp. The third-row building at the extreme left end of the village housed the Israeli team. The group of buildings is shown directly north of the twin poles holding up the Figure 1 1972 Olympic Games Village Sports Hall roof. It was these buildings where the terrorists broke in. used in the operation had not received proper training as sharpshooters. Add to that, they were improperly located, Negotiations too few, and lacked radios to communicate with each other and with the command post. The snipers were armed with The Black September terrorists demanded the release of over assault rifles rather than sniper rifles, and their weapons 200 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons and two left-wing lacked long-range scopes and night-vision capabilities. extremists in German prisons. German negotiators were Second, the officers on the plane who were supposed to willing to accept their demands, but Israel rejected them. subdue the terrorists unanimously chose to abandon their Israel’s Prime Minister Golda Meir stated, “If we give in post. -

The Blue State: UNRWA's Transition from Relief to Development in Providing Education to Palestinian Refugees in Jordan

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-1-2021 The Blue State: UNRWA's Transition from Relief to Development in Providing Education to Palestinian Refugees in Jordan Alana Mitias University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Arabic Studies Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Mitias, Alana, "The Blue State: UNRWA's Transition from Relief to Development in Providing Education to Palestinian Refugees in Jordan" (2021). Honors Theses. 1699. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1699 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BLUE STATE: UNRWA’S TRANSITION FROM RELIEF TO DEVELOPMENT IN PROVIDING EDUCATION TO PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN JORDAN by Alana Michelle Mitias A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, Mississippi April 2021 Approved by ____________________________ Advisor: Dr. Lauren Ferry ____________________________ Reader: Dr. Emily Fransee ____________________________ Reader: Professor Ashleen Williams © 2021 Alana Michelle Mitias ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………..…………..1 CHAPTER II: INTERNATIONAL DIMENSION & LEGAL FRAMEWORK………....8 CHAPTER III: JORDAN’S EVOLUTION AS A HOST STATE………………...…….20 CHAPTER IV: UNRWA’S TRANSITION FROM RELIEF TO DEVELOPMENT…...38 CHAPTER V: ANALYSIS……………………………………………………………...50 CHAPTER VI: CONCLUSION………………………………………………………...56 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………….61 iii “An expenditure for education by UNRWA should not be regarded as relief any more than is a similar expenditure by any Government or by UNESCO. -

The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on US Textile and Apparel

Office of Industries Working Paper ID-053 September 2018 The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on U.S. Textile and Apparel Trade Mahnaz Khan Abstract Certain U.S. bilateral or multilateral free trade agreements contain tariff preference levels (TPLs) that permit a limited quantity of specified finished textile and/or apparel goods to enter the U.S. market at preferential duty rates despite not meeting the agreement’s required tariff shift rules. This article seeks to examine the effect of TPL provisions that have expired, or will expire in 2018, on U.S. textile and apparel imports and exports from certain FTA partners, including Bahrain, Nicaragua and Costa Rica (under CAFTA-DR), Morocco, Oman, and Singapore. It will discuss import and export trends after TPL implementation and in some cases, TPL expiration, in the context of an FTA partners’ industry structure and competitiveness as a U.S. textile and apparel supplier. Such trends vary widely across countries, and analysis of the factors influencing these trade flows suggests that the effectiveness of TPLs is dependent upon myriad factors, including the structure of the partner country’s textile and apparel sector, the country’s competitiveness as a U.S. supplier, and existence or absence of relationships with U.S. textile firms. Disclaimer: Office of Industries working papers are the result of the ongoing professional research of USITC staff and solely represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. These papers do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. The Impact of Tariff Preference Levels on U.S. -

10 Ecosy Congress

10 TH ECOSY CONGRESS Bucharest, 31 March – 3 April 2011 th Reports of the 9 Mandate ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” CONTENTS Petroula Nteledimou ECOSY President p. 3 Janna Besamusca ECOSY Secretary General p. 10 Brando Benifei Vice President p. 50 Christophe Schiltz Vice President p. 55 Kaisa Penny Vice President p. 57 Nils Hindersmann Vice President p. 60 Pedro Delgado Alves Vice President p. 62 Joan Conca Coordinator Migration and Integration network p. 65 Marianne Muona Coordinator YFJ network p. 66 Michael Heiling Coordinator Pool of Trainers p. 68 Miki Dam Larsen Coordinator Queer Network p. 70 Sandra Breiteneder Coordinator Feminist Network p. 71 Thomas Maes Coordinator Students Network p. 72 10 th ECOSY Congress 2 Held thanks to hospitality of TSD Bucharest, Romania 31 st March - 3 rd April 2011 9th Mandate reports ECOSY – Young European Socialists “Talking about my generation” Petroula Nteledimou, ECOSY President Report of activities, 16/04/2009 – 01/04/2011 - 16-19/04/2009 : ECOSY Congress , Brussels (Belgium). - 24/04/2009 : PES Leaders’ Meeting , Toulouse (France). Launch of the PES European Elections Campaign. - 25/04/2009 : SONK European Elections event , Helsinki (Finland). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 03/05/2009 : PASOK Youth European Elections event , Drama (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 04/05/2009 : Greek Women’s Union European Elections debate , Kavala (Greece). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. - 07-08/05/2009 : European Youth Forum General Assembly , Brussels (Belgium). - 08/05/2009 : PES Presidency meeting , Brussels (Belgium). - 09-10/05/2009 : JS Portugal European Election debate , Lisbon (Portugal). Speaker on behalf of ECOSY. -

QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY of the STATE of QATAR ______TABLE of CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1

CASE CONCERNING MARITIME DELIMITATION AND TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS BETWEEN QATAR AND BAHRAIN (QATAR V. BAHRAIN) REPLY OF THE STATE OF QATAR _____________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION CHAPTER I - GENERAL 1 Section 1. Qatar's Case and Structure of Qatar's Reply Section 2. Deficiencies in Bahrain's Written Pleadings Section 3. Bahrain's Continuing Violations of the Status Quo PART II - THE GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND CHAPTER II - THE TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY OF QATAR Section 1. The Overall Geographical Context Section 2. The Emergence of the Al-Thani as a Political Force in Qatar Section 3. Relations between the Al-Thani and Nasir bin Mubarak Section 4. The 1913 and 1914 Conventions Section 5. The 1916 Treaty Section 6. Al-Thani Authority throughout the Peninsula of Qatar was consolidated long before the 1930s Section 7. The Map Evidence CHAPTER III - THE EXTENT OF THE TERRITORY OF BAHRAIN Section 1. Bahrain from 1783 to 1868 Section 2. Bahrain after 1868 PART III - THE HAWAR ISLANDS AND OTHER TERRITORIAL QUESTIONS CHAPTER IV - THE HAWAR ISLANDS Section 1. Introduction: The Territorial Integrity of Qatar and Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 2. Proximity and Qatar's Title to the Hawar Islands Section 3. The Extensive Map Evidence supporting Qatar's Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands Section 4. The Lack of Evidence for Bahrain's Claim to have exercised Sovereignty over the Hawar Islands from the 18th Century to the Present Day Section 5. The Bahrain and Qatar Oil Concession Negotiations between 1925 and 1939 and the Events Leading to the Reversal of British Recognition of Hawar as part of Qatar Section 6. -

A Realpolitik Reassessment

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 178 From Camp David to Oslo: A Realpolitik Reassessment Sep 17, 1998 Brief Analysis he peace process has, in practice, meant Israel's acceptance by the Arab world. This process, however, is not T irreversible. It is mainly a function of Israel's military, economic, and strategic strength and the Arab recognition of structural weakness. Only as long as current conditions hold, the peace process will continue. The American role in the peace process is important yet should not be overstated. Much has occurred without the involvement of the United States. The Oslo Accord, which occurred without American knowledge of the negotiations, is a primary example. The peace treaty between Jordan and Israel also did not have much input from the United States. To be sure, a change in U.S. policy toward increased isolationism could significantly threaten the peace process. Realpolitik Reasons for the Peace Process. The root cause for the peace process has been several realist considerations: Reaction to past conflict. Failed attempts to eliminate Israel by military means have forced the Arab world, however reluctantly, to accept Israel. The use of force has proven too difficult and too costly in dealing with Israel. In addition, Arab recognition of Israel's nuclear capabilities has reinforced the notion that Israel is militarily strong and cannot be easily removed from the map. Weariness toward war has also forced the countries of the region to redefine their national goals. Populations have grown tired of protracted conflict. This has led to a willingness to discuss the possibility of peace by all nations in the region. -

North Gaza Industrial Zone – Concept Note

North Gaza Industrial Zone – Concept Note A Private Sector-Led, Growth and Employment Promoting Solution December 19, 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction: Purpose and Structure of the Concept Note 5 Chapter One: Current Realities of the Gaza Economy and Private Sector 6 The Macro Economic Anomaly of Gaza: the Role of External Aid, and the Impact of Political Conditions and Restrictions 6 Role of External Aid 6 The Effect of Political Developments and Restrictions 8 The Impact of Gaza on Palestine's Macro Economic Indicators 9 Trade Activity 9 Current Situation of the Private Sector in Gaza 12 Chapter Two: The proposed Solution - North Gaza Industrial Zone (NGIZ) 13 A New Vision for Private- Sector-Led Economic Revival of Gaza 13 The NGIZ – Concept and Modules 13 Security, Administration and Management of the NGIZ 14 The Economic Regime of the NGIZ and its Development through Public Private Partnership 16 The NGIZ - Main Economic Features and Benefits 18 Trade and Investment Enablers 19 Industrial Compounds 20 Agricultural Compounds 22 Logistical Compounds 24 Trade and Business Compounds 24 Energy, Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Compounds 26 The Erez Land Transportation Compound 27 The Gaza Off-Shore Port Compound 27 Chapter Three: Macro-Economic Effects in comparison to relevant case studies 29 Effect on Employment 29 Effect on Exports and GDP 30 Are Such Changes Realistic? Evidence and Case Studies 33 Evidence from Palestinian and Gazan Economic History 35 List of References 36 Annex A: Private Sector Led Economic Revival of Gaza – An Overview 38 Introduction: The Economic Potential of Gaza 38 Weaknesses and strengths of the Private Sector in Gaza 38 Development Strategy Based on Leveraging Strengths 40 Political Envelope and Economic Policy Enabling Measures 41 Trade Policy Enablers 42 Export and Investment Promotion Measures 44 Solutions for the Medium and Longer Terms 45 2 Executive Summary The purpose of this concept note is to propose a politically and economically feasible solution that can start the economic revival of Gaza. -

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: F Political Science Volume 14 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue: An Experimental Study of University Students in Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates By Muhammad Asim Government Postgraduate College Asghar Mall, Pakistan Abstract- This study aimed to measure public opinion in the Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates regarding peaceful solution of Palestine issue Data (N=276) was collected from two universities, one postgraduate college and one degree college in Pakistan, two universities in Iran and two universities in United Arab Emirates. Although, Pakistan and Iran have theocratic environment and we got anti-Israel replies but there were 77 Pakistani and 41 Emirati students who presented their rational views about peaceful solution of this conflict. There is a brief debate on One-State Solution, Two-States Solution, Three-States Solution and the status of Jerusalem. The plan of forming union among the territories of Israel and Palestine, single currency and Rail-Road plan for secular transportation from one region to another is also discussed in this study. During comparing such public opinion with other previous international proposals for resolving this issue, recommendations from the author are presented in the last. Keywords: uae, i-p union, religiosity, eu, state of judea. -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

THE PLO and the PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London

THE PLO AND THE PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London The emergence of a durable Palestinian nationalism was one of the more remarkable developments in the history of the modern Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. This was largely due to a generation of young activists who proved particularly adept at capturing the public imagination, and at seizing opportunities to develop autonomous political institutions and to promote their cause regionally and internationally. Their principal vehicle was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while armed struggle, both as practice and as doctrine, was their primary means of mobilizing their constituency and asserting a distinct national identity. By the end of the 1970s a majority of countries – starting with Arab countries, then extending through the Third World and the Soviet bloc and other socialist countries, and ending with a growing number of West European countries – had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The United Nations General Assembly meanwhile confirmed the right of the stateless Palestinians to national self- determination, a position adopted subsequently by the European Union and eventually echoed, in the form of support for Palestinian statehood, by the United States and Israel from 2001 onwards. None of this was a foregone conclusion, however. Britain had promised to establish a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine when it seized the country from the Ottoman Empire in 1917, without making a similar commitment to the indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants. In 1929 it offered them the opportunity to establish a self-governing agency and to participate in an elected assembly, but their community leaders refused the offer because it was conditional on accepting continued British rule and the establishment of the Jewish ‘national home’ in what they considered their own homeland. -

Imagining the Border: Option for Resolution the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1.