A Feminist Reading of an Unfinished Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Woman and Nature: an Ecofeminist Study of Indira Goswami's

Volume: II, Issue: II ISSN: 2581-5857 An International Peer-Reviewed GAP BODHI TARU - Open Access Journal of Humanities WOMAN AND NATURE: AN ECOFEMINIST STUDY OF INDIRA GOSWAMI’S Dr. Sadaf Shah Sr. Assistant Professor Department of English University of Jammu The Blue-necked God In 1970s, Ecofeminism emerged as a social and political movement with the increasing consciousness of the connections between women and nature. Ecofeminists believe that there is a close relationship between the domination of nature and exploitation of woman. French feminist Françoise d’Eaubonne who first coined the term “Ecofeminism” in her book Feminism or Death (1974) urges the women to lead ecological revolution to save the planet Earth and form new relationships between humanity and nature as well as man and woman. The development of ecofeminism is greatly affected by both ecological movements and feminism. Indira Goswami is a well known writer from one of the north east states of India namely Assam. In her fictional writings, she has shown strong ecofeminist concerns. In the novel The Blue- necked God, Goswami depicts the exploitation and poverty of widows, who have been left behind in the holy city of lord Krishna, Vrindavan by their families after the death of their husbands. Both widows and nature are exploited by men. Man is shown as cruel and greedy who can go to any extent in exploiting woman and degrading environment for his own progress. It is the woman only who shares a close bond with nature and contributes to its protection and preservation. Key words: Ecofeminism, Widows, Women, Nature, Men, Exploitation, Oppression, Preservation, Protection, Degradation, Solace. -

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications MONOGRAPHS (MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE) Amrita Pritam (Punjabi writer) By Sutinder Singh Noor Pp. 96, Rs. 40 First Edition: 2010 ISBN 978-81-260-2757-6 Amritlal Nagar (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Narinder Bhullar Pp. 116, First Edition: 1996 ISBN 81-260-0088-0 Rs. 15 Baba Farid (Punjabi saint-poet) By Balwant Singh Anand Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 88, Reprint: 1995 Rs. 15 Balwant Gargi (Punjabi Playright) By Rawail Singh Pp. 88, Rs. 50 First Edition: 2013 ISBN: 978-81-260-4170-1 Bankim Chandra Chatterji (Bengali novelist) By S.C. Sengupta Translated by S. Soze Pp. 80, First Edition: 1985 Rs. 15 Banabhatta (Sanskrit poet) By K. Krishnamoorthy Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 96, First Edition: 1987 Rs. 15 Bhagwaticharan Verma (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Baldev Singh ‘Baddan’ Pp. 96, First Edition: 1992 ISBN 81-7201-379-5 Rs. 15 Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (Punjabi scholar and lexicographer) By Paramjeet Verma Pp. 136, Rs. 50.00 First Edition: 2017 ISBN: 978-93-86771-56-8 Bhai Vir Singh (Punjabi poet) By Harbans Singh Translated by S.S. Narula Pp. 112, Rs. 15 Second Edition: 1995 Bharatendu Harishchandra (Hindi writer) By Madan Gopal Translated by Kuldeep Singh Pp. 56, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1984 Bharati (Tamil writer) By Prema Nand kumar Translated by Pravesh Sharma Pp. 103, Rs.50 First Edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-81-260-4291-3 Bhavabhuti (Sanskrit poet) By G.K. Bhat Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 80, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1983 Chandidas (Bengali poet) By Sukumar Sen Translated by Nirupama Kaur Pp. -

TDC-Hindi (Regular)

20 B.A. REGULAR Sl No. Paper Code Paper Title CORE COURSE 1 HIN-RC-1016 Hindi Sahitya Ka Itihas 2 HIN-RC-2016 Madhyakalin Hindi Kavita 3 HIN-RC-3016 Adhunik Hindi Kavita 4 HIN-RC-4016 Hindi Gadya Sahitya Skill Enhancement Course 1 HIN-SE-3014 Karyalayin Anuvad 2 HIN-SE-4014 Anuvad Vijnan 3 HIN-SE-5014 Rang Aalekh aur Rangmanch 4 HIN-SE-6014 Bhasha-Shikshan Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) 1 HIN-RE-5016 Lok-Sahitya/Kabir 2 HIN-RE-6016 Hindi ki Rashtriya Kavyadhara/ Rekhachitra tatha Sansmaran GenerIC Elective (GE) (any two) 1 HIN-RG-5016 Kala aur Sahitya/ Sangit evam Sahitya 2 HIN-RG-6016 Adhunik Asamiya Kahani/ Sarjanatmak Lekhan ke vividh Rup B.A. General Programme(MIL) 1 HIN-CC-3016 Hindi Kavya-Dhara 2 HIN-CC-4016 Hindi Katha-Sahitya 21 Programme Template: B.A. Regular Sem TY CORE AECC SEC DSE GEN este PE r CR 12X6=72 2X4=8 4X4=!6 4X6=24 2X6=12 ED IT I ENG-CC-1016 ENG-AE- HIN-RC-1016 1014/ ZZZ-RC-1016 ASM-AE-1014 II ENG-CC-2016 ENV-AE-2014 HIN-RC-2016 ZZZ-RC-2016 III HIN/ HIN-SE-3014 ALT-CC-3016 HIN-RC-3016 ZZZ-RC-3016 IV HIN/ HIN-SE-4014 ALT-CC-4016 HIN-RC-4016 ZZZ-RC-4016 V HIN-SE-5014 HIN-RE-5016 HIN-RG- ZZZ-RE-5016 5016 VI HIN-SE-6014 HIN-RE-6016 HIN-RG- ZZZ-RE-6016 6016 22 B.A. (PROGRAMME) HINDI (reg) (CORE COURSE) HIN-RC-1016 Hindi Sahitya Ka Itihas Full Marks: 100 External: 80 Internal: 20 Credits: 6 (L : 4 + T : 2) UNIT 1 Adikal Simankan, Namkaran, Paristhitiyan, Siddha Sahitya, Nath Sahitya, Jain Sahitya, Raso Kavya UNIT 2 Bhaktikal Simankan, Namkaran,Paristhitiyan,Sant Kavya, Sufi Kavya, Ram Kavya, Krishna Kavya UNIT 3 Ritikal C. -

Translation Today

Translation Today Editors Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair Volume 8, Number 2, 2014 Editors Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair Assistant Editors Geethakumary V. Abdul Halim Editorial Board Avadhesh Kumar Singh School of Translation Studies, IGNOU K.C. Baral EFLU, Shilong Campus Giridhar Rathi New Delhi Subodh Kumar Jha Magadh University Sushant Kumar Mishra School of Languages, IGNOU A.S. Dasan University of Mysore Ch.Yashawanta Singh Manipuri University Mazhar Asif Gauhati University K.S. Rao Sahitya Akademi iii Translation Today Volume 8 No.2, 2014 Editors: Awadesh Kumar Mishra V. Saratchandran Nair © Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, 2014. This material may not be reproduced or transmitted, either in part or in full, in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from : Prof. Awadesh Kumar Mishra Director Central Institute of Indian Languages, Manasagangotri, Hunsur Road, Mysore – 570 006, INDIA Phone: 0091/ 0821 -2515820 (Director) Pabx: 0091/ 0821 -2345052 Grams: BHARATI Fax: 0091/ 0821 -2345218 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ciil.org (Director) www.ntm.org.in To contact Head, Publications ISSN-0972-8740 Single Issue: INR 200; US $ 6: EURO 5; POUND 4 including postage (air-mail) Published by Prof. Awadesh Kumar Mishra, Director Designed By : Nandakumar L, NTM, CIIL, Mysore Printed by M.N. Chandrashekar CIIL Printing Press, Manasagangotri, Hunsur Road Mysore – 570 006, India iv In This Issue EDITORIAL 1 ARTICLES Translation Theories and Translating Assamese Texts 5 Manjeet Baruah Translation: An Inter-Cultural Textual Transference 31 Shamala Ratnakar Role of Translation in Comparative Literature 40 Surjeet Singh Warwal The Ghost of the Author and the Afterlife of Translation 61 Farheena Danta and Bijay K Danta Translation as Handloom: Acknowledging Family as (Re-) Source 76 Akshaya Kumar Discerning the Intimacies of Intertextuality: A. -

Tumkur University 2017-18

TUMKURTUMKUR UNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY TUMKUR UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2017-18 EXTRACT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE ACADEMIC COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 27.10.2018 SUB NO: 2018-19: 3ꃇ ಸಾ.풿.ಪ:01:ಸಾ.ಅ:04,颿ನಕ:27.10.2018 Approval of University Annual Report 2017-18 DECISION: Academic Council has approved the draft Annual Report for the year 2017-18 and recommended to submit it to the approval of the Syndicate and to the Government at the earliest. EXTRACT OF THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE SYNDICATE MEETING HELD ON 29.10.2018 SUB NO: 2018-19: 4ꃇ ಸಾ.ಸ: 04: ಸಾ/ಅ:01, 颿ನಕ:29.10.2018 Approval of University Annual Report 2017-18 DECISION: The Syndicate has approved the draft Annual Report for the year 2017-18 which was approved by the Academic Council. The Syndicate recommended submitting the report to the Government at the earliest. CONTENTS Sl. No Particulars Page No. 1 Statutory Authorities of University : 1 2 Statutory Officers : 1 3 Human Resource Development Section : 10 4 Academic Section : 16 5 General and Development Section : 28 6 Finance Section : 36 7 Examination Section : 51 8 Engineering Section : 68 9 University Library : 72 10 Physical Education and Sports : 83 11 National Service Scheme : 86 12 Prasaranga : 89 DEPARTMENTS OF STUDIES AND RESEARCH 13 Dr. D. V. Gundappa Kannada Adhyana Kendra : 90 14 Department of Studies and Research in English : 101 15 Department of Studies and Research in History and Archaeology : 108 16 Department of Studies and Research in Economics : 115 17 Department of Studies and Research in Political Science : 132 18 Department -

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels

Postmodern Traces and Recent Hindi Novels Veronica Ghirardi University of Turin, Italy Series in Literary Studies Copyright © 2021 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, Suite 1200 C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Wilmington, Delaware, 19801 Malaga, 29006 United States Spain Series in Literary Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020952110 ISBN: 978-1-62273-880-9 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press using elements designed by pch.vector / Freepik. To Alessandro & Gabriele If you can't explain it simply, you don't understand it well enough Albert Einstein Table of contents Foreword by Richard Delacy ix Language, Literature and the Global Marketplace: The Hindi Novel and Its Reception ix Acknowledgements xxvii Notes on Hindi terms and transliteration xxix Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1. -

Indira Goswami - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Indira Goswami - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Indira Goswami(14 November 1942 – 29 November 2011) Indira Goswami (Assamese: ??????? ????????, Hindi: ??????? ????????, Tamil: ??????? ????????), known by her pen name Mamoni Raisom Goswami and popularly as Mamoni Baideo, was an Assamese editor, poet, professor, scholar and writer. She was the winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award (1983), the Jnanpith Award (2001) and Principal Prince Claus Laureate (2008). A celebrated writer of contemporary Indian literature, many of her works have been translated into English from her native Assamese which include The Moth Eaten Howdah of the Tusker, Pages Stained With Blood and The Man from Chinnamasta. She was also well known for her attempts to structure social change, both through her writings and through her role as mediator between the armed militant group United Liberation Front of Asom and the Government of India. Her involvement led to the formation of the People's Consultative Group, a peace committee. She referred to herself as an "observer" of the peace process rather than as a mediator or initiator. Her work has been performed on stage and in film. The film Adajya is based on her novel won international awards. Words from the Mist is a film made on her life directed by Jahnu Barua. <b> Early Life and Dducation </b> Indira Goswami was born in Guwahati to Umakanta Goswami and Ambika Devi, a family that was deeply associated with Sattra life of the Ekasarana Dharma. She studied at Latashil Primary School, Guwahati; Pine Mount School, Shillong; and Tarini Charan Girls' School, Guwahati and completed Intermediate Arts from Handique Girls' College, Guwahati. -

Name Dr. Purabi Goswami Photographs Department English

Name Dr. Purabi Goswami Photographs Department English Designation Assistant Professor E-mail ID [email protected] Mobile Number 9613283796 Specialisation Women and Literature & Translation Studies Area of Interest Translation Studies Awards and Achievements Awarded M. Phil. by EFLU, Hyderabad in the year 2008. Teaching Experience More than 10 years Orientation & Refresher Course attended 1. Participated in a Refresher Course on Art and Craft of North-East India at HRDC, Gauhati University from 18th December 2017 to 7th January, 2018. 2. Participated in a Refresher Course in English, HRDC, Gauhati University from 8th to 28th November, in the year 2010. 3. Participated in an Orientation Course, HRDC, Gauhati University From 2nd to 29th November, in the year 2009. Research Project Carried out & Guidance Doing a teacher led students’ project entitled Representation of Insurgency: A Study of Select Novels in English from the State of Assam. Academic Association 1. Life Member of Forum on Contemporary Theory, Vadodara. 2. Life Member of North East India Network for Academic Discourse (NEINAD), Gauhati University. Research Paper 1. Title - Women and Translation: Reading Mamoni Raisam Goswami’s “The Empty Chest” Journal – The Criterion, December, 2015 2. Title - Translation as Interpretation: Reading Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s An Unfinished Autobiography. Journal - edhvani, an e- journal of the Dept. of Comparative Literature, Hyderabad University, July, 2013. 3. Title – Translation and Culture: Translating Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s Theng Fhakhri Tahsildarar Tamar Tarowal Journal – Transcript, Dept. of English, Bodoland University, in 2013 4. Title -Story Telling in Githa Hariharan’s When Dreams Travel. Journal - The Marginal Voice, a journal published by the Dept of MIL, Gauhati University, May, 2011. -

Jnanpith Award * *

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * The Jnanpith Award (also spelled as Gyanpeeth Award ) is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa Kannada 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali 1972 Ramdhari Singh Dinkar Hindi Dattatreya Ramachandra Bendre Kannada 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Oriya 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi 1975 P. V. Akilan Tamil 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali 1977 K. Shivaram Karanth Kannada 1978 Sachchidananda Vatsyayan Hindi 1979 Birendra Kumar Bhattacharya Assamese 1980 S. K. Pottekkatt Malayalam 1981 Amrita Pritam Punjabi 1982 Mahadevi Varma Hindi 1983 Masti Venkatesha Iyengar Kannada 1984 Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai Malayalam 1985 Pannalal Patel Gujarati www.sirssolutions.in 91+9830842272 Email: [email protected] Please Post Your Comment at Our Website PAGE And our Sirs Solutions Face book Page Page 1 of 2 TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Jnanpith Award * * Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1986 Sachidananda Routray Oriya 1987 Vishnu Vaman Shirwadkar (Kusumagraj) Marathi 1988 C. Narayanareddy Telugu 1989 Qurratulain Hyder Urdu 1990 V. K. Gokak Kannada 1991 Subhas Mukhopadhyay Bengali 1992 Naresh Mehta Hindi 1993 Sitakant Mahapatra Oriya 1994 U. -

Reflection on Humanity in Mamoni Raisom Goswami's Novel “TEZ

Reflection on Humanity in Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s Novel “TEZ ARU DHULIRE DHUKHARITA PRISTHA”: A Study PJAEE, 17 (7) (2020) Reflection on Humanity in Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s Novel “TEZ ARU DHULIRE DHUKHARITA PRISTHA”: A Study Purbalee Gohain Cotton University, Assam, India Email: [email protected] Purbalee Gohain. Reflection on Humanity in Mamoni Raisom Goswami’s Novel “TEZ ARU DHULIRE DHUKHARITA PRISTHA”: A Study--Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 17(7), 14387-14390. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Enriching, Discrimination, Exploitation, Humanity, Anxious. Abstract Mamoni Raisom Goswami was one of the renowned and memorable names in the history of world literature. She was widely known for enriching the culture ofAssamese novel. The main objective of her literary work revolves around the welfare of mankind. She dedicated herself to literature with the motive of reviving people from all kinds of injustice, discrimination and exploitation. Humanity was always her main source of inspiration. The basis of the novel “TezAruDhulireb DhukhoritoPristha” displays the principles of humanity, although its pages are full of bloodshed and dust. Dr. Goswami has based the novel on the mass killings in Delhi which occurred due to political reasons. One part of the novel depicts inhumane, barbaric, greedy, cowardliness, thirst and impulsive nature of human beings. On the other hand, the novel takes the novelist Dr Goswami to roam around the civilized and the dark streets of Delhi and Lucknow with a desire to know people as they are and to feel the compassion of one human towards the other. The humane novelist is also anxious to know the comfort and sufferings of the prostitutes residing in those brothel. -

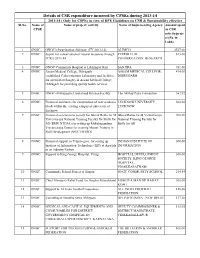

Details of CSR Expenditure Incurred by Cpses During 2013-14 2013-14 ( Only for Cspes in View of DPE Guidelines on CSR & Sustainability Effective Sl.No

Details of CSR expenditure incurred by CPSEs during 2013-14 2013-14 ( Only for CSPEs in view of DPE Guidelines on CSR & Sustainability effective Sl.No. Name of Name of project/ activity Name of Implementing Agency Amount spent CPSE on CSR activity/proje ct (Rs. in Lakh) 1 ONGC ONGC's Swavlamban Abhiyan: (FY 2013-14) ALIMCO 2527.00 2 ONGC Suport for conservation of natural resources through PETROLEUM 613.00 PCRA 2013-14 CONSERVATION RESEARCH 3 ONGC ONGC Community Hospital at Lakhimpur Keri SANJIDA 451.00 4 ONGC Assam Medical College, Dibrugarh: ASSAM MEDICAL COLLEGE , 414.00 established Catheterization Laboratory and facilities DIBRUGARH for open Heart Surgery in Assam Medical College, Dibrugarh for providing quality health services 5 ONGC ONGC-Akshaypatra Centralised Kitchen Facility The Akshay Patra Foundation 363.92 6 ONGC Financial assistance for construction of new academic LUCKNOW UNIVERSITY , 300.00 block within the existing campus of university of LUCKNOW Lucknow 7 ONGC Financial assistance to society for Bharat Ratna Sir M Bharat Ratna Sir M Visvesvaraya 300.00 Visvesvaraya National Training Facility for Skills for National Training Facility for All (BMV NTFSA) for setting up Mokshagundam Skills for All Visvesvaraya Centre for training Master Trainers in Skill Development (MVCTMTSD) 8 ONGC Financial support to Tripura govt. for setting up INDIAN INSTITUTE OF 300.00 Institute of Information Technology (IIIT) at Agartala INFORMATION as an industry Partner 9 ONGC Support to King George Hospital, Vizag HOSPITAL DEVELOPMENT 300.00 -

Jnanpith Award

Jnanpith Award JNANPITH AWARD The Jnanpith Award is an Indian literary award presented annually by the Bharatiya Jnanpith to an author for their "outstanding contribution towards literature". Instituted in 1961, the award is bestowed only on Indian writers writing in Indian languages included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and English, with no posthumous conferral. The Bharatiya Jnanpith, a research and cultural institute founded in 1944 by industrialist Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain, conceived an idea in May 1961 to start a scheme "commanding national prestige and of international standard" to "select the best book out of the publications in Indian languages". The first recipient of the award was the Malayalam writer G. Sankara Kurup who received the award in 1965 for his collection of poems, Odakkuzhal (The Bamboo Flute), published in 1950. In 1976, Bengali novelist Ashapoorna Devi became the first woman to win the award and was honoured for the 1965 novel Pratham Pratisruti (The First Promise), the first in a trilogy. Year Recipient(s) Language(s) 1965 G. Sankara Kurup Malayalam (1st) 1966 Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay Bengali (2nd) 1967 Umashankar Joshi Gujarati (3rd) 1967 Kuppali Venkatappa Puttappa 'Kuvempu' Kannada (3rd) 1 Download Study Materials on www.examsdaily.in Follow us on FB for exam Updates: ExamsDaily Jnanpith Award 1968 Sumitranandan Pant Hindi (4th) 1969 Firaq Gorakhpuri Urdu (5th) 1970 Viswanatha Satyanarayana Telugu (6th) 1971 Bishnu Dey Bengali (7th) 1972 Ramdhari Singh 'Dinkar' Hindi (8th) 1973 D. R. Bendre Kannada (9th) 1973 Gopinath Mohanty Odia (9th) 1974 Vishnu Sakharam Khandekar Marathi (10th) 1975 Akilan Tamil (11th) 1976 Ashapoorna Devi Bengali (12th) 1977 K.