The Use of Central Nervous System Active Drugs During Pregnancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness Et Al

USOO6264,917B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,264,917 B1 Klaveness et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 24, 2001 (54) TARGETED ULTRASOUND CONTRAST 5,733,572 3/1998 Unger et al.. AGENTS 5,780,010 7/1998 Lanza et al. 5,846,517 12/1998 Unger .................................. 424/9.52 (75) Inventors: Jo Klaveness; Pál Rongved; Dagfinn 5,849,727 12/1998 Porter et al. ......................... 514/156 Lovhaug, all of Oslo (NO) 5,910,300 6/1999 Tournier et al. .................... 424/9.34 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (73) Assignee: Nycomed Imaging AS, Oslo (NO) 2 145 SOS 4/1994 (CA). (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 19 626 530 1/1998 (DE). patent is extended or adjusted under 35 O 727 225 8/1996 (EP). U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. WO91/15244 10/1991 (WO). WO 93/20802 10/1993 (WO). WO 94/07539 4/1994 (WO). (21) Appl. No.: 08/958,993 WO 94/28873 12/1994 (WO). WO 94/28874 12/1994 (WO). (22) Filed: Oct. 28, 1997 WO95/03356 2/1995 (WO). WO95/03357 2/1995 (WO). Related U.S. Application Data WO95/07072 3/1995 (WO). (60) Provisional application No. 60/049.264, filed on Jun. 7, WO95/15118 6/1995 (WO). 1997, provisional application No. 60/049,265, filed on Jun. WO 96/39149 12/1996 (WO). 7, 1997, and provisional application No. 60/049.268, filed WO 96/40277 12/1996 (WO). on Jun. 7, 1997. WO 96/40285 12/1996 (WO). (30) Foreign Application Priority Data WO 96/41647 12/1996 (WO). -

Profile Profile Profile Profile Uses and Administration Adverse Effects And

640 Antihistamines Propiomazine Hydrochloride {BANM, r!NNMJ P..r�p�rc:Jti()n.� ............................ m (details are given in Volume B) propiorf,azina; to o azine; Chiorhydrate ProprietaryPreparations HidrodoruroPropi<;>rn deazini HydrochloridP pium; f1ponvtot,la3Y!Ha China: Qi Qi Hung. : de; Single-ingredient Preparafions. Loderixt. CIH'f); rMAPOX!10p!'\A. C;cJcl1_,--N_,QS,HCI�3.76_91 Rupatadine is an antihistamine with platelet-activating CAS 240) 5-9. factor (PAF) antagonist activity that is used for the Terfenadine (BAN, USAN, r!NN) treatment of allergic rhinitis (p. 612.1) and chronic 1 idiopathic urticaria (p. 612.3). It is given as the fumarate although doses are expressed in terms of the base; rupatadine fumarate 12.8 mg is equivalent to about 10 mg of rupatadine. The usual oral dose is the equivalent of 10 mg once daily of rupatadine. Izquierdo I. et a!. Rupatadine: a new selective histamine HI receptor and platelet-activating factor (PAF) antagonist: a review of pharmacological profile and clinical management of allergic rhinitis. Drugs Today 2003; 39: 451-68. 2. Kearn SJ,Plosker GL. Rupatadine: a review of its use in the management of allergic disorders. Drugs 2007; 67: 457-74. 3. Fantin et at. International Rupatadine study group. A 12-week 5, 8: (Terfenadine). A white or almost white, placebo-controlled study of rupatadine 10 mg once daily compared with Ph. Bur. cetirizine IO mg once daily, in the treatment of persistent allergic crystalline powder. It shows polymorphism. Very slightly rhinitis. Allergy 2008; 63: 924-3 1. soluble in water and in dilute hydrochloric acid; freely 4. -

The Use of Central Nervous System Active Drugs During Pregnancy

Pharmaceuticals 2013, 6, 1221-1286; doi:10.3390/ph6101221 OPEN ACCESS pharmaceuticals ISSN 1424-8247 www.mdpi.com/journal/pharmaceuticals Review The Use of Central Nervous System Active Drugs During Pregnancy Bengt Källén 1,*, Natalia Borg 2 and Margareta Reis 3 1 Tornblad Institute, Lund University, Biskopsgatan 7, Lund SE-223 62, Sweden 2 Department of Statistics, Monitoring and Analyses, National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm SE-106 30, Sweden; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Clinical Pharmacology, Linköping University, Linköping SE-581 85, Sweden; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-46-222-7536, Fax: +46-46-222-4226. Received: 1 July 2013; in revised form: 10 September 2013 / Accepted: 25 September 2013 / Published: 10 October 2013 Abstract: CNS-active drugs are used relatively often during pregnancy. Use during early pregnancy may increase the risk of a congenital malformation; use during the later part of pregnancy may be associated with preterm birth, intrauterine growth disturbances and neonatal morbidity. There is also a possibility that drug exposure can affect brain development with long-term neuropsychological harm as a result. This paper summarizes the literature on such drugs used during pregnancy: opioids, anticonvulsants, drugs used for Parkinson’s disease, neuroleptics, sedatives and hypnotics, antidepressants, psychostimulants, and some other CNS-active drugs. In addition to an overview of the literature, data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register (1996–2011) are presented. The exposure data are either based on midwife interviews towards the end of the first trimester or on linkage with a prescribed drug register. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

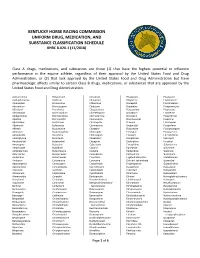

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Drugs and Medication Guidelines Brochure

Equine Medication Monitoring Program Drugs and Medication Guidelines January 2021 1 Introduction The California Equine Medication Monitoring Program (EMMP) is an industry funded program to ensure the integrity of public equine events and sales in California through the control of performance and disposition enhancing drugs and permitting limited therapeutic use of drugs and medications. The EMMP and the industry is dedicated and committed to promote the health, welfare and safety of the equine athlete. Owners, trainers, exhibitors, veterinarians and consignors of equines to public sales have a responsibility to be familiar with the California EMMP and the California Equine Medication Rule. California law (Food and Agricultural Code Sections 24000-24018) outlines the equine medication rule for public equine events in California. The owner, trainer and consignor have responsibility to ensure full compliance with all elements of the California Equine Medication Rule. Owners, trainers, exhibitors, veterinarians and consignors of equines to public sales must comply with both the California Equine Medication Rule and any sponsoring organization drug and medication rule for an event. The more stringent medication rule applies for the event. The California Equine Medication Rule is posted on the website: http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/ahfss/Animal_Health/emmp/ The information contained in this document provides advice regarding the California Equine Medication Rule and application of the rule to practical situations. The EMMP recognizes that situations arise where there is an indication for legitimate therapeutic treatment near the time of competition at equine events. The EMMP regulations permit the use of therapeutic medication in certain circumstances to accommodate legitimate therapy in compliance with the requirements of the rule. -

Sedative and Hypnotic Drugs-Fatal and Non-Fatal Reference Blood Concentrations, 2014, Forensic Science International, (236), 138-145

Sedative and hypnotic drugs-Fatal and non- fatal reference blood concentrations Anna K Jönsson, Carl Soderberg, Ketil Arne Espnes, Johan Ahlner, Anders Eriksson, Margareta Reis and Henrik Druid Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Anna K Jönsson, Carl Soderberg, Ketil Arne Espnes, Johan Ahlner, Anders Eriksson, Margareta Reis and Henrik Druid, Sedative and hypnotic drugs-Fatal and non-fatal reference blood concentrations, 2014, Forensic Science International, (236), 138-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.01.005 Copyright: Elsevier http://www.elsevier.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-105408 Our reference: FSI 7480 P-authorquery-v9 AUTHOR QUERY FORM Journal: FSI Please e-mail or fax your responses and any corrections to: E-mail: [email protected] Article Number: 7480 Fax: +353 6170 9272 Dear Author, Please check your proof carefully and mark all corrections at the appropriate place in the proof (e.g., by using on-screen annotation in the PDF file) or compile them in a separate list. Note: if you opt to annotate the file with software other than Adobe Reader then please also highlight the appropriate place in the PDF file. To ensure fast publication of your paper please return your corrections within 48 hours. For correction or revision of any artwork, please consult http://www.elsevier.com/artworkinstructions. Any queries or remarks that have arisen during the processing of your manuscript are listed below and highlighted by flags in the proof. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DIX to the HTSUS—Continued

20558 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 80 / Wednesday, April 26, 1995 / Notices DEPARMENT OF THE TREASURY Services, U.S. Customs Service, 1301 TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL APPEN- Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DIX TO THE HTSUSÐContinued Customs Service D.C. 20229 at (202) 927±1060. CAS No. Pharmaceutical [T.D. 95±33] Dated: April 14, 1995. 52±78±8 ..................... NORETHANDROLONE. A. W. Tennant, 52±86±8 ..................... HALOPERIDOL. Pharmaceutical Tables 1 and 3 of the Director, Office of Laboratories and Scientific 52±88±0 ..................... ATROPINE METHONITRATE. HTSUS 52±90±4 ..................... CYSTEINE. Services. 53±03±2 ..................... PREDNISONE. 53±06±5 ..................... CORTISONE. AGENCY: Customs Service, Department TABLE 1.ÐPHARMACEUTICAL 53±10±1 ..................... HYDROXYDIONE SODIUM SUCCI- of the Treasury. NATE. APPENDIX TO THE HTSUS 53±16±7 ..................... ESTRONE. ACTION: Listing of the products found in 53±18±9 ..................... BIETASERPINE. Table 1 and Table 3 of the CAS No. Pharmaceutical 53±19±0 ..................... MITOTANE. 53±31±6 ..................... MEDIBAZINE. Pharmaceutical Appendix to the N/A ............................. ACTAGARDIN. 53±33±8 ..................... PARAMETHASONE. Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the N/A ............................. ARDACIN. 53±34±9 ..................... FLUPREDNISOLONE. N/A ............................. BICIROMAB. 53±39±4 ..................... OXANDROLONE. United States of America in Chemical N/A ............................. CELUCLORAL. 53±43±0 -

Psychopharmacologic Therapy 2828 Valerie Levi, Pharm D Deborah Antai-Otong, MS, RN, CNS, PMHNP, CS, FAAN Duane F

Psychopharmacologic Therapy 2828 Valerie Levi, Pharm D Deborah Antai-Otong, MS, RN, CNS, PMHNP, CS, FAAN Duane F. Pennebaker, PhD, FNAP, FRCNA Joy Riley, DNSc, RN, CS CHAPTER OUTLINE The Human Genome and Pharmacology Protein Binding The Brain and Behavior Active Metabolites Neuroanatomical Structures Relevant Cultural Considerations to Behavior Psychopharmacologic Therapeutic Agents Cortical Structures Medication Administration The Cerebral Cortex Antidepressants The Four Lobes and Their Functions Mood Stabilizers The Association Cortices Anticonvulsants The Basal Ganglia Antipsychotics The Hippocampus and the Amygdala Sedatives and Hypnotic Agents Subcortical Structures Psychopharmacologic Therapy across The Brainstem the Life Span The Cerebellum Sedative and Antianxiety Agents The Diencephalon Antipsychotics Neurophysiology and Behavior Children and Adolescents Neurons Antipsychotics Synaptic Transmission Antidepressants Neurotransmitters Mood Stabilizers Biogenic Amines Sedative and Antianxiety Agents Acetylcholine Older Adults Amino Acids Antidepressants Peptides Mood Stabilizers Neurotransmitter Action Sedative and Antianxiety Agents Pharmacokinetic Concepts Antipsychotics Pharmacology The Role of the Nurse Factors That Include Drug Intensity and The Generalist Nurse Duration The Advanced-Practice Psychiatric Absorption Registered Nurse Distribution Treatment Adherence Metabolism Legal and Ethical Issues Elimination Client Advocacy Steady State, Half-Life, and Clearance Steady State Right to Refuse Half-Life Psychoeducation Clearance Medication Monitoring 767 768 UNIT THREE Therapeutic Interventions Competencies Upon completion of this chapter, the learner should be able to: 1. Describe current knowledge about the brain and 4. Explain the nurse’s role in the administration behavior as it relates to the clinical and pharmaco- and prescription of psychopharmacologic agents kinetics of the major psychopharmacologic agents. within the treatment regime. 2. Describe the clinical and pharmacologic proper- 5. -

2004 Guide to Psychiatric Drug Interactions Sheldon H

Av Referencein Pocketailable Format —pg. 59 Educational Review Primary Psychiatry. 2004;11(2):39-60 2004 Guide to Psychiatric Drug Interactions Sheldon H. Preskorn, MD, and David Flockhart, MD, PhD drug alone but is either more than or Focus Points less than what would normally be • In a drug-drug interaction (DDI), the presence of a second drug alters the expected for the specific dose ingested. nature, magnitude, or duration of the effect of a given dose of a first drug. “Altered duration” means that the These interactions can be therapeutic or adverse, planned or unintended, nature of the effect is reasonably the but are always determined by the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinet- same as can be expected from the victim ics of the drugs involved rather than their therapeutic indication. drug alone, but the effect either is short- • The risk of unintended and untoward DDIs is increasing in concert with er or longer lived than would normally both the increasing number of pharmaceuticals available and the number of be expected for the dose given. patients on multiple medications. The goal of this guide is to provide a quick reference for prescribers about • To avoid adverse DDIs, the prescriber must keep in mind fundamental prin- some of the major psychiatric DDIs. ciples of pharmacology and good clinical management. Furthermore, it presents general con- • The prescriber must know all of the medications that the patient is taking cepts which can aid prescribers in and be able to use available knowledge about their pharmacodynamic and avoiding untoward DDIs when possible pharmacokinetic mechanisms to minimize the risk of untoward DDIs. -

Efficacy, Acceptability, and Tolerability of All Available Treatments for Insomnia in the Elderly: a Systematic Review and Netwo

Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020: 142: 6–17 © 2020 The Authors. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd All rights reserved ACTA PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA DOI: 10.1111/acps.13201 Systematic Review Or Meta-Analysis Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of all available treatments for insomnia in the elderly: a systematic review and network meta-analysis Samara MT, Huhn M, Chiocchia V, Schneider-Thoma J, Wiegand M, M. T. Samara1,2 , M. Huhn1,3, Salanti G, Leucht S. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of all V. Chiocchia4, J. Schneider- available treatments for insomnia in the elderly: a systematic review and Thoma1, M. Wiegand1, network meta-analysis. G. Salanti4, S. Leucht 1 Objectives: Symptoms of insomnia are highly prevalent in the elderly. A 1 significant number of pharmacological and non-pharmacological Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, School of Medicine, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technical University interventions exist, but, up-to-date, their comparative efficacy and of Munich, Munich, Germany, 23rd Department of safety has not been sufficiently assessed. Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Aristotle University of Methods: We integrated the randomized evidence from every available Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 3Department of treatment for insomnia in the elderly (>65 years) by performing a Psychiatry, Psychosomatic Medicine and Psychotherapy, network meta-analysis. Several electronic databases were searched up to Social Foundation Bamberg, Teaching Hospital of the May 25, 2019. The two primary outcomes were total sleep time and University of Erlangen, Erlangen, Germany and 4Institute sleep quality. Data for other 6 efficacy and 8 safety outcomes were also of Social and Preventive Medicine (ISPM), University of analyzed. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Material Article Title: Patient Characteristics Associated With Use of Lurasidone Versus Other Atypical Antipsychotics in Patients With Bipolar Disorder: Analysis From a Claims Database in the United States Author(s): Mauricio Tohen, MD, DrPH, MBA; Daisy Ng-Mak, PhD; Krithika Rajagopalan, PhD; Rachel Halpern, PhD; Chien-Chia Chuang, PhD; and Antony Loebel, MD DOI Number: https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.16m02066 List of Supplementary Material for the article 1. Table 1 2. Table 2 Disclaimer This Supplementary Material has been provided by the author(s) as an enhancement to the published article. It has been approved by peer review; however, it has undergone neither editing nor formatting by in-house editorial staff. The material is presented in the manner supplied by the author. It is illegal to post this copyrighted PDF on any website. ♦ © 2017 Copyright Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. © Copyright 2017 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc. ICD‐9‐CM Table 1. Diagnosis Codes to Identify Psychological Comorbidities, Substance Abuse, or ConditionAlcohol Abuse ICD‐9‐CM Description Diagnosis Code Adjustment 309.XX Adjustment reaction disorder Anxiety 293.84 Anxiety disorder in conditions classified elsewhere disorder 300.0X Anxiety states 300.10 Hysteria, unspecified 300.3 Obsessive‐compulsive disorders Attention deficit 314.XX Attention deficit disorder disorder Substance abuse 292.0 Drug withdrawal 292.85 Drug‐induced sleep disorders 292.89‐292.9 Drug‐induced mental disorders 304.0X‐304.2X, Drug dependence (excluding cannabis) 304.4X‐304.9X 305.3X‐305.9X Nondependent abuse of drugs Alcohol abuse 291.0, 291.81 Alcohol withdrawal 291.1‐291.3, 291.5 Alcohol‐induced psychotic disorders 291.82 Alcohol induced sleep disorders 291.89, 291.9 Alcohol‐induced mental disorders 303.XX Alcohol dependence syndrome 305.0X Nondependent alcohol abuse It is illegal to post this copyrighted PDF on any website.