Paleoradiology Imaging Mummies and Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPR 2013 Postgraduate Course May 14-15, 2013 SAM Questionnaire Tuesday, May 14, 2013 CHEST Digital Radiography Robert Macdougal

SPR 2013 Postgraduate Course May 14-15, 2013 SAM Questionnaire Tuesday, May 14, 2013 CHEST Digital Radiography Robert MacDougall, MSc 1. Which of the following is unaffected by the selection of Value of Interest Look Up Table (VOI-LUT): A. Diagnostic information in the processed image B. Target Exposure (ET) C. Exposure Index (EI) D. Deviation Index (DI) E. Brightness and contrast of the displayed image Correct Answer: B 2. Exposure Index (EI) represents: A. The exposure at the entrance to the patient B. The exposure at the detector plane measured with an ion chamber C. The brightness of the displayed image D. The exposure at the detector calculated from the mean signal response of the detector within the Values of Interest E. The deviation from a target exposure Correct Answer: D References 1. An Exposure Indicator for Digital Radiography: Report of AAPM Task Group 116. American Association of Physicists in Medicine. Accessed April 10, 2013. https://www.aapm.org/pubs/reports/RPT_116.pdf 2. Internation Electrotechnical Commission. Medical Electrical Equipment. Exposure Index of Digital X-ray Imaging Systems - Part 1: Definitions and Requirements for General Radiography. IEC Publication No. 62494-1. Geneva, Switzerland: International Electrotechnical Commission, 2002. Functional Chest MR Imaging Hyun Woo Goo, MD, PhD 3. Which one of the followings is the LEAST likely limitation of thoracic MR imaging? A. Low signal-to-noise ratio due to the low proton density of the lung B. Potential hazards from ionizing radiation C. Motion artifacts from respiratory motion and cardiac pulsation D. Relatively long examination time E. Susceptibility artifacts from multiple air-tissue interfaces Correct Answer: B References 1. -

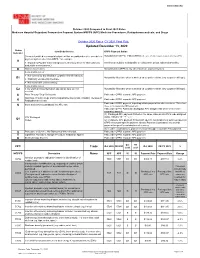

Updated December 13, 2020

WWW.SNMMI.ORG October 2020 Compared to Final 2021 Rates Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System HOPPS (APC) Medicine Procedures, Radiopharmaceuticals, and Drugs October 2020 Rates CY 2021 Final Rule Updated December 13, 2020 Status Item/Code/Service OPPS Payment Status Indicator Services furnished to a hospital outpatient that are paid under a fee schedule or Not paid under OPPS. Paid by MACs under a fee schedule or payment system other than OPPS. payment system other than OPPS,* for example: A ● Separately Payable Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory Services (Not subject to Services are subject to deductible or coinsurance unless indicated otherwise. deductible or coinsurance.) D Discontinued Codes Not paid under OPPS or any other Medicare payment system. Items and Services: ● Not covered by any Medicare outpatient benefit category Not paid by Medicare when submitted on outpatient claims (any outpatient bill type). E1 ● Statutorily excluded by Medicare ● Not reasonable and necessary Items and Services: E2 ● for which pricing information and claims data are not Not paid by Medicare when submitted on outpatient claims (any outpatient bill type). available G Pass-Through Drug/ Biologicals Paid under OPPS; separate APC payment NonPass-Through Drugs and nonimplantable Biologicals, including Therapeutic Paid under OPPS; separate APC payment K Radiopharmaceuticals Paid under OPPS; payment is packaged into payment for other services. Therefore, Items and Services packaged into APC rate N there is no separate APC payment. Paid under OPPS; Addendum B displays APC assignments when services are separately payable. (1) Packaged APC payment if billed on the same claim as a HCPCS code assigned STV-Packaged status indicator “S,” “T,” or “V.” Q1 Codes (2) Composite APC payment if billed with specific combinations of services based on OPPS composite-specific payment criteria. -

Don Brothwell 1933-2016: a Tribute to a Polymath

Don Brothwell 1933-2016: A tribute to a polymath Don Brothwell, Professor and then Emeritus Professor of Human Palaeoecology at York, with members of the BioArCh team in the Department of Archaeology, University of York (courtesy of Malin Holst) As a person and as a scholar, Don Brothwell had an incredible influence on so many people around the world for so many years, and his legacy continues to do so. However, it is a very daunting task to write a short celebration of his life in archaeological science, and particularly in bioarchaeology, because he did so much for us! He himself had just written and published his memoirs (2016), the Archaeopress website describing it as ‘the first memoir by an internationally known archaeological scientist, and one who has been particularly research active for over fifty years in the broad field of bioarchaeology’. Beyond the references I have cited for this piece, I would highly recommend this as a fascinating read for all (see contents list below); just look at what he has done and where he has travelled as a starting point! What a role model for being an academic. Some of what I will say here is already on York University’s website for Don as a personal tribute to him (http://www.york.ac.uk/archaeology/staff/academic-staff/in- memoriam-don-brothwell/), but here I am describing some of his remarkable achievements through what he published. First, though, we should celebrate his contributions, in general, to archaeological science. How did that all start? Well, he did “science” A levels in biology, chemistry and geology and then studied for a BSc in Archaeology and Anthropology from 1952 at the Institute of Archaeology, University College, London. -

Criteria for Acceptability of Medical Radiological Equipment Used in Diagnostic Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Radiotherapy

EUROPEAN COMMISSION RADIATION PROTECTION N° 162 Criteria for Acceptability of Medical Radiological Equipment used in Diagnostic Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Radiotherapy Directorate-General for Energy Directorate D — Nuclear Safety & Fuel Cycle Unit D4 — Radiation Protection 2012 This report was prepared by Quality Assurance Reference Centre for the European Commission under contract N°. ENER/10/NUCL/SI2.581655 and represents those organisations’ views on the subject matter. The views and opinions expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission’s views. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012 ISBN 978-92-79-27747-4 doi: 10.2768/22561 © European Union, 2012 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Luxembourg 2 FOREWORD Luxembourg, October 2012 The work of the European Commission in the field of radiation protection is governed by the Euratom Treaty and the secondary legislation adopted under it. Council Directive 97/43/Euratom (the Medical Exposure Directive, MED) is the legal act defining the Euratom requirements on radiation protection of patients and of other individuals submitted to medical exposure. -

Diagnostic Radiology Physics Diagnostic This Publication Provides a Comprehensive Review of Topics Relevant to Diagnostic Radiology Physics

A Handbook for Teachers and Students A Handbook for Teachers Diagnostic Diagnostic This publication provides a comprehensive review of topics relevant to diagnostic radiology physics. It is intended to provide the basis for the education of medical physicists in the field of diagnostic radiology. Bringing together the work of 41 authors and reviewers from 12 countries, the handbook covers a broad range of topics including radiation physics, dosimetry and Radiology instrumentation, image quality and image perception, imaging modality specific topics, recent advances in digital techniques, and radiation biology and protection. It is not designed to replace the large number of textbooks available on many aspects of diagnostic radiology physics, but is expected Radiology Physics Physics to fill a gap in the teaching material for medical radiation physics in imaging, providing in a single manageable volume the broadest coverage of topics currently available. The handbook has been endorsed by several international professional bodies and will be of value to those preparing for their certification A Handbook for as medical physicists, radiologists and diagnostic radiographers. Teachers and Students D.R. Dance S. Christofides A.D.A. Maidment I.D. McLean K.H. Ng Technical Editors International Atomic Energy Agency Vienna ISBN 978–92–0–131010–1 1 @ DIAGNOSTIC RADIOLOGY PHYSICS: A HANDBOOK FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GHANA OMAN ALBANIA GREECE PAKISTAN ALGERIA GUATEMALA -

European Meeting of the Paleopathology Association

. 14TH EUROPEAN MEETING OF THE PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION PROGRAM - ABSTRACTS 14TH EMPPA 2002 COIMBRA, 28 – 31 AUGUST, 2002 http://emppa2002.uc.pt [email protected] EDITOR DEPARTAMENTO DE ANTROPOLOGIA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA PORTUGAL ISBN 972 - 9006 - 42 - 3 Copyright © 2002, Departamento de Antropologia da Universidade de Coimbra . 14TH EUROPEAN MEETING OF THE PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION HONORARY COMMITTEE Minister of Science and High Education, Prof. Dr. Pedro Lynce Rector of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Fernando Rebelo President of the Direction Board of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Lélio Quaresma Mayor of Coimbra, Dr. Carlos Encarnação President of the Paleopathology Association, Prof. Dr. Michael Schultz Emerita President of the Paleopathology Association, Ms. Eve Cockburn Professor Decano in Anthropology, Prof. Dr. Manuel Laranjeira Rodrigues de Areia President of the Department of Anthropology of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Cristina Padez Coordinator of the Anthropological Museum, University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Paulo Gama SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Don Brothwell (UK) Alejandro Pérez-Pérez (Spain) Domingo Campillo (Spain) Mary Lucas Powell (USA) Luigi Capasso (Italy) Charlotte Roberts (United Kingdom) Éric Crubézy (France) Conrado Rodriguez-Martín (Spain) Eugénia Cunha (Portugal) Michael Schultz (Germany) Olivier Dutour (France) Sheila Mendonça de Souza (Brazil) Francisco Etxeberria (Spain) Eugen -

Diffraction-Enhanced X-Ray Imaging of in Vitro Breast Tumours

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI REPORT SERIES IN PHYSICS HU-P-D113 DIFFRACTION-ENHANCED X-RAY IMAGING OF IN VITRO BREAST TUMOURS Jani Keyriläinen Division of X-ray Physics Department of Physical Sciences Faculty of Science University of Helsinki Helsinki, Finland Department of Oncology Helsinki University Central Hospital Helsinki, Finland ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki, for public criticism in Auditorium D101 of the Department of Physical Sciences (Physicum), Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2, on October 29th, 2004, at 12 o’clock noon. Helsinki 2004 ISSN 0356-0961 ISBN 952-10-1655-8 ISBN 952-10-1656-6 (pdf-version) http://ethesis.helsinki.fi/ Helsinki 2004 Yliopistopaino PREFACE This thesis is based on research done at the Division of X-ray Physics, Department of Physical Sciences, University of Helsinki (HU, Finland), at the Medical Beamline ID17, European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France), and at the departments of Oncology, Pathology and Radiology, Helsinki University Central Hospital (HUCH, Finland), all of which are acknowledged. I wish to express my gratitude to Professor Juhani Keinonen, Ph.D., Head of the Department of Physical Sciences, and to Professor Seppo Manninen, Ph.D., former Head of the Division of X-ray Physics, for the opportunity to work at the Department. I also wish to thank Professor Heikki Joensuu, M.D., Ph.D., Head of the Department of Oncology, and William Thomlinson, Ph.D., former Beamline Responsible, ID17, for allowing me to use the outstanding working facilities of their institutions. I am most grateful to my supervisors, Professor Pekka Suortti, Ph.D., Department of Physical Sciences, and Docent Mikko Tenhunen, Ph.D., Chief Physicist of the Department of Oncology, for proposing to me the topic of this study and guiding me throughout this research work. -

Whole Body MR

Whole Body MR: Techniques and Staging in Oncology ‐ How To • Extent of disease and staging • Response to treatment – Early assessment of response to treatment may allow more individualized therapy • Surveillance • Complications – Osteonecrosis – Infection • Cancer predisposition syndromes screening Condition Associated neoplasms Surveillance NF type I Optic nerve glioma, neurofibromas, leukemia (especially juvenile Annual physical examination; annual ophthalmologic examination in early childhood (to age 5 y); regular myelomonocytic leukemia developmental assessment and blood pressure monitoring; appropriate monitoring by a specialist and myelodysplastic syndromes, MPNST (lifetime risk of 8%–13%), GIST according to CNS, skeletal, or cardiovascular abnormalities (lifetime risk of 6%), pheochromocytoma (1%), rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma Beckwith- Wilms tu (40%–43%), hepatoblastoma (12-20%), adrenocortical ca, Abdominal US every 3 mo to age 7 y; measurement of serum AFP level every 3 mo to age 4 y; daily Wiedemann neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma abdominal examination by the caretaker at the discretion of the caretaker or parent; abdominal syndrome examination by a physician every 6 mo MEN 1 Parathyroid gland adenomas (65%–90%), pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors Screening starting at age 5–10 y, including measurement of fasting glucose, calcium, PTH, insulin, (50%–70%), and anterior pituitary gland adenomas (25%–65%) prolactin, and IGF1 levels; annual pancreatic US; pancreatic and pituitary MR imaging every 3–5 y; yearly abdominal CT or MR -

Whole Body Low Dose Computed Tomography (WBLDCT) Can Be Comparable to Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging (WBMRI) in the Assessment of Multiple Myeloma

diagnostics Article Whole Body Low Dose Computed Tomography (WBLDCT) Can Be Comparable to Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging (WBMRI) in the Assessment of Multiple Myeloma Davide Ippolito 1,2,* , Teresa Giandola 1,2, Cesare Maino 1,2 , Davide Gandola 1,2 , Maria Ragusi 1,2, Pietro Andrea Bonaffini 2,3 and Sandro Sironi 2,3 1 Department of Diagnostic Radiology, “San Gerardo” Hospital, via Pergolesi 33, 20900 Monza, MB, Italy; [email protected] (T.G.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (M.R.) 2 School of Medicine, University of Milano-Bicocca, via Cadore 48, 20900 Monza, MB, Italy; pa.bonaffi[email protected] (P.A.B.); [email protected] (S.S.) 3 Department of Diagnostic Radiology, H Papa Giovanni XXIII, Piazza OMS 1, 24127 Bergamo, BG, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Aim of the study is to compare the agreement between whole-body low-dose computed tomography (WBLDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) in the evaluation of bone marrow involvement in patients with multiple myeloma (MM). Patients with biopsy-proven MM, who underwent both WBLDCT and WBMRI were retrospectively enrolled. After identifying the presence of focal bone involvement (focal infiltration pattern), the whole skeleton was divided into five Citation: Ippolito, D.; Giandola, T.; anatomic districts (skull, spine, sternum and ribs, pelvis, and limbs). Patients were grouped according Maino, C.; Gandola, D.; Ragusi, M.; to the number and location of the lytic lesions (<5, 5–20, and >20) and Durie and Salmon staging Bonaffini, P.A.; Sironi, S. Whole Body system. The agreement between CT and MRI regarding focal pattern, staging, lesion number, and Low Dose Computed Tomography distribution was assessed using the Cohen Kappa statistics. -

Meeting Program

. 14TH EUROPEAN MEETING OF THE PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION PROGRAM - ABSTRACTS 14TH EMPPA 2002 COIMBRA, 28 – 31 AUGUST, 2002 http://emppa2002.uc.pt [email protected] EDITOR DEPARTAMENTO DE ANTROPOLOGIA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA PORTUGAL ISBN 972 - 9006 - 42 - 3 Copyright © 2002, Departamento de Antropologia da Universidade de Coimbra . 14TH EUROPEAN MEETING OF THE PALEOPATHOLOGY ASSOCIATION HONORARY COMMITTEE Minister of Science and High Education, Prof. Dr. Pedro Lynce Rector of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Fernando Rebelo President of the Direction Board of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Lélio Quaresma Mayor of Coimbra, Dr. Carlos Encarnação President of the Paleopathology Association, Prof. Dr. Michael Schultz Emerita President of the Paleopathology Association, Ms. Eve Cockburn Professor Decano in Anthropology, Prof. Dr. Manuel Laranjeira Rodrigues de Areia President of the Department of Anthropology of the Faculty of Sciences and Technology of the University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Cristina Padez Coordinator of the Anthropological Museum, University of Coimbra, Prof. Dr. Paulo Gama SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Don Brothwell (UK) Alejandro Pérez-Pérez (Spain) Domingo Campillo (Spain) Mary Lucas Powell (USA) Luigi Capasso (Italy) Charlotte Roberts (United Kingdom) Éric Crubézy (France) Conrado Rodriguez-Martín (Spain) Eugénia Cunha (Portugal) Michael Schultz (Germany) Olivier Dutour (France) Sheila Mendonça de Souza (Brazil) Francisco Etxeberria (Spain) Eugen -

Whole-Body Imaging of the Musculoskeletal System: the Value of MR Imaging

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by PubMed Central Skeletal Radiol (2007) 36:1109–1119 DOI 10.1007/s00256-007-0323-5 REVIEW ARTICLE Whole-body imaging of the musculoskeletal system: the value of MR imaging Gerwin P. Schmidt & Maximilian F. Reiser & Andrea Baur-Melnyk Received: 17 December 2006 /Revised: 25 March 2007 /Accepted: 9 April 2007 / Published online: 7 June 2007 # ISS 2007 Abstract In clinical practice various modalities are used Keywords Whole-body . Imaging . Musculoskeletal . for whole-body imaging of the musculoskeletal system, Magnetic resonance imaging including radiography, bone scintigraphy, computed tomog- raphy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). Introduction Multislice CT is far more sensitive than radiographs in the assessment of trabecular and cortical bone destruction and The skeletal system is a frequent target of metastatic spread allows for evaluation of fracture risk. The introduction of from various primary tumors like carcinoma of the breast, combined PET-CT scanners has markedly increased diag- lung and prostate cancer. Moreover, primary malignancies nostic accuracy for the detection of skeletal metastases may also originate from the bone marrow, such as lymphoma compared with PET alone. The unique soft-tissue contrast and multiple myeloma [1]. Therefore, it is highly important of MRI enables for precise assessment of bone marrow to accurately assess manifestations of malignant diseases infiltration and adjacent soft tissue structures so that within the bone marrow in order to facilitate adequate alterations within the bone marrow may be detected before therapy and predict prognosis. osseous destruction becomes apparent in CT or metabolic Only pronounced destruction of bone with loss of bone changes occur on bone scintigraphy or PET scan. -

PET Coding Review and Resources

Volume 3, Issue 3 SUMMER 2006 pet center of excellence newsletter SNM Members Appointed to National Academy of Sciences PET Coding Review Committee to Review State of Nuclear Medicine and Resources By Denise A. Merlino, MBA, CNMT, CPC, FSNMTS Peter S. Conti, immediate past president of ET is a technology that continues to evolve, and coding, coverage, and payment both SNM and the PET Center of Excellence, Psystems have been evolving along with it. In March of 2005, PET providers and a number of other SNM members were transitioned from using complicated “G” series Healthcare Common Procedure Cod- recently named to the National Academy of ing System (HCPCS) codes to the American Medical Association (AMA) Current Sciences (NAS) ad hoc committee of experts Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for Medicare-covered indications. Last January, to review the “state of the science” for nuclear PET radiopharmaceutical HCPCS codes were changed for FDG and rubidium. Finally, medicine. in May, the National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR) went into operation providing “The 13-month $700,000 study will pro- Medicare coverage of FDG PET studies for all cancer indications that did not fall under vide the opportunity to validate the importance the current national coverage determination (NCD) policy. of basic nuclear medicine research,” said Every change brings with it the need to train staff, update billing software, and make Conti, a professor of radiology, pharmacy and certain that all billing procedures are in compliance with the new regulations. The list biomedical engineering at the University of below summarizes the top 10 things you need to know about coding PET today.