Lychnos 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yngve Brilioth Svensk Medeltidsforskare Och Internationell Kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV

SIM SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF MISSION RESEARCH PUBLISHER OF THE SERIES STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA & MISSIO PUBLISHER OF THE PERIODICAL SWEDISH MISSIOLOGICAL THEMES (SMT) This publication is made available online by Swedish Institute of Mission Research at Uppsala University. Uppsala University Library produces hundreds of publications yearly. They are all published online and many books are also in stock. Please, visit the web site at www.ub.uu.se/actashop Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV Carl F. Hallencreutz Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare UTGIVENAV Katharina Hallencreutz UPPSALA 2002 Utgiven med forord av Katharina Hallencreutz Forsedd med engelsk sammanfattning av Bjorn Ryman Tryckt med bidrag fran Vilhelm Ekmans universitetsfond Kungl.Vitterhets Historie och Antivkvitetsakademien Samfundet Pro Fide et Christianismo "Yngve Brilioth i Uppsala domkyrkà', olja pa duk (245 x 171), utford 1952 av Eléna Michéew. Malningen ags av Stiftelsen for Âbo Akademi, placerad i Auditorium Teologicum. Foto: Ulrika Gragg ©Katharina Hallencreutz och Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 91-85424-68-4 Cover design: Ord & Vetande, Uppsala Typesetting: Uppsala University, Editorial Office Printed in Sweden by Elanders Gotab, Stockholm 2002 Distributor: Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning P.O. Box 1526,751 45 Uppsala Innehall Forkortningar . 9 Forord . 11 lnledning . 13 Tidigare Briliothforskning och min uppgift . 14 Mina forutsattningar . 17 Yngve Brilioths adressater . 18 Tillkommande material . 24 KAPITEL 1: Barndom och skolgang . 27 1 hjartat av Tjust. 27 Yngve Brilioths foraldrar. 28 Yngve Brilioths barndom och forsta skolar . 32 Fortsatt skolgang i Visby. 34 Den sextonarige Yngve Brilioths studentexamen. 36 KAPITEL 2: Student i Uppsala . -

Jacob Van Ruisdael Gratis Epub, Ebook

JACOB VAN RUISDAEL GRATIS Auteur: P. Biesboer Aantal pagina's: 168 pagina's Verschijningsdatum: 2002-04-13 Uitgever: Waanders EAN: 9789040096044 Taal: nl Link: Download hier Dutch Painting April 8 - 14 works 95 0. January 20 - 7 works 60 0. Accept No, rather not. Add to my sets. Share it on Facebook. Share on Twitter. Pin it on Pinterest. Back to top. Similarly at this early stage of his career he absorbed some influence of contemporary landscape painters in Haarlem such as Jan van Goyen, Allart van Everdingen, Cornelis Vroom and Jacob van Mosscher. We intend to illustrate this with a selection of eight earlier works by these artists. However, there are already some remarkable differences to be found. Ruisdael developed a more dramatic effect in the rendering of the different textures of the trees, bushes and plants and the bold presentation of one large clump of oak trees leaning over with its gnarled and twisted trunks and branches highlighted against the dark cloudy sky. Strong lighting hits a sandy patch or a sandy road creating dramatic colour contrasts. These elements characterize his early works from till It is our intention to focus on the revolutionary development of Ruisdael as an artist inventing new heroic-dramatic schemes in composition, colour contrast and light effects. Our aim is to follow this deveopment with a selection of early signed and dated paintings which are key works and and show these different aspects in a a series of most splendid examples, f. Petersburg, Leipzig, München and Paris. Rubens en J. Brueghel I. Ruisdael painted once the landscape for a group portrait of De Keyser Giltaij in: Sutton et al. -

Making Amusement the Vehicle of Instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900

1 ‘Making amusement the vehicle of instruction’: Key Developments in the Nursery Reading Market 1783-1900 PhD Thesis submitted by Lesley Jane Delaney UCL Department of English Literature and Language 2012 SIGNED DECLARATION 2 I, Lesley Jane Delaney confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ABSTRACT 3 ABSTRACT During the course of the nineteenth century children’s early reading experience was radically transformed; late eighteenth-century children were expected to cut their teeth on morally improving texts, while Victorian children learned to read more playfully through colourful picturebooks. This thesis explores the reasons for this paradigm change through a study of the key developments in children’s publishing from 1783 to 1900. Successively examining an amateur author, a commercial publisher, an innovative editor, and a brilliant illustrator with a strong interest in progressive theories of education, the thesis is alive to the multiplicity of influences on children’s reading over the century. Chapter One outlines the scope of the study. Chapter Two focuses on Ellenor Fenn’s graded dialogues, Cobwebs to catch flies (1783), initially marketed as part of a reading scheme, which remained in print for more than 120 years. Fenn’s highly original method of teaching reading through real stories, with its emphasis on simple words, large type, and high-quality pictures, laid the foundations for modern nursery books. Chapter Three examines John Harris, who issued a ground- breaking series of colour-illustrated rhyming stories and educational books in the 1810s, marketed as ‘Harris’s Cabinet of Amusement and Instruction’. -

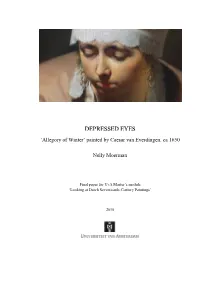

Depressed Eyes

D E P R E S S E D E Y E S ‘ Allegory of Winter’ painted by Caesar van Everdingen, c a 1 6 5 0 Nelly Moerman Final paper for UvA Master’s module ‘Looking at Dutch Seventeenth - Century Paintings’ 2010 D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 2 CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 3 2. ‘Allegory o f Winter’ by Caesar van Everdingen, c. 1650 3 3. ‘Principael’ or copy 5 4. Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17 - 1678), his life and work 7 5. Allegorical representations of winter 10 6. What is the meaning of the painting? 11 7. ‘Covering’ in a psychological se nse 12 8. Look - alike of Lady Winter 12 9. Arguments for the grief and sorrow theory 14 10. The Venus and Adonis paintings 15 11. Chronological order 16 12. Conclusion 17 13. Summary 17 Appendix I Bibliography 18 Appendix II List of illustrations 20 A ppen dix III Illustrations 22 Note: With thanks to the photographic services of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam for supplying a digital reproduction. Professional translation assistance was given by Janey Tucker (Diesse, CH). ISBN/EAN: 978 - 90 - 805290 - 6 - 9 © Copyright N. Moerman 2010 Information: Nelly Moerman Doude van Troostwijkstraat 54 1391 ET Abcoude The Netherlands E - mail: [email protected] D EPRESSED EYES || Nelly Moerman - 3 1. Introduction When visiting the Rijksmuseum, it seems that all that tourists w ant to see is Rembrandt’s ‘ Night W atch ’. However, before arriving at the right spot, they pass a painting which makes nearly everybody stop and look. What attracts their attention is a beautiful but mysterious lady with her eyes cast down. -

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033

Sotheby's Old Master & British Paintings Evening Sale London | 08 Jul 2015, 07:00 PM | L15033 LOT 14 THE PROPERTY OF A LADY JACOB ISAACKSZ. VAN RUISDAEL HAARLEM 1628/9 - 1682 AMSTERDAM HILLY WOODED LANDSCAPE WITH A FALCONER AND A HORSEMAN signed in monogram lower right: JvR oil on canvas 101 by 127.5 cm.; 39 3/4 by 50 1/4 in. ESTIMATE 500,000-700,000 GBP PROVENANCE Lady Elisabeth Pringle, London, 1877; With Galerie Charles Sedelmeyer, Paris, 1898; Mrs. P. C. Handford, Chicago; Her sale, New York, American Art Association, 30 January 1902, lot 59; William B. Leeds, New York; His sale, London, Sotheby’s, 30 June 1965, lot 25; L. Greenwell; Anonymous sale ('The Property of a Private Collector'), New York, Sotheby’s, 7 June 1984, lot 76, for $517,000; Gerald and Linda Guterman, New York; Their sale, New York, Sotheby’s, 14 January 1988, lot 32; Anonymous sale New York, Sotheby’s, 2 June 1989, lot 16, for $297,000; With Verner Amell, London 1991; Acquired from the above by Hans P. Wertitsch, Vienna; Thence by family descent. EXHIBITED London, Royal Academy, Winter Exhibition, 1877, no. 25; New York, Minkskoff Cultural Centre, The Golden Ambience: Dutch Landscape Painting in the 17th Century, 1985, no. 10; Hamburg, Kunsthalle, Jacob van Ruisdael – Die Revolution der Landschaft, 18 January – 1 April 2002, and Haarlem, Frans Hals Museum, 27 April – 29 July 2002, no. 31; Vienna, Akademie der Bildenden Künste, on loan since 2010. LITERATURE C. Sedelmeyer, Catalogue of 300 paintings, Paris 1898, pp. 1967–68, no. 175, reproduced; C. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before

FRANS JANSZ. POST (c. 1612 – Haarlem - 1680) A Landscape in Brazil Signed, lower left: F. POST On panel, 8 x 10½ ins. (20.3 x 26.6 cm) Provenance: European private collection By descent within the family since the eighteenth century Literature: Q. Buvelot, ‘Review of P. and B. Correa do Lago, Frans Post, 1612- 1680; ‘catalogue raisonné, in The Burlington Magazine, vol. CL, no. 1259, February 2008, p. 117, n. 2 VP4713 The Haarlem painter Frans Post occupies a unique position in Dutch seventeenth-century art. The first professionally trained European artist to paint the landscape of the New World, as far as we know, he devoted his entire production to views of Brazil. In 1630, the Dutch seized control of the Portuguese settlement in north-eastern Brazil. The young Prince Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679) was appointed Governor General of the new territory and charged with establishing a secure footing for the Dutch West India Company. On 25 October 1636, he set sail for South America accompanied by a team of artists and scientists, including the landscapist Frans Post and the figure painter Albert Eckhout (c. 1610-1665). The expedition arrived at Recife in January the following year. Post remained there for seven years, during which time he made a visual record of the flora and fauna, as well as the topography of the region, before returning to the Netherlands in 1644. Yet of the many paintings and drawings made during his South American sojourn, only seven paintings and a sketchbook, preserved in the Scheepvaart Museum, in Amsterdam, survive today. -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Print Format

Allaert van Everdingen (Alkmaar 1621 - Amsterdam 1675) Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest brush and grey and brown wash 11.1 x 12.8 cm (4⅜ x 5 in) The Month of August (Virgo): The Harvest has an extended and fascinating provenance. Sold as part of a complete set of the twelve months in 1694 to the famed Amsterdam writer and translator Sybrand I Feitama (1620-1701), it was passed down through the literary Feitama family who were avid collectors of seventeenth-century Dutch works on paper.¹ The present work was separated from the other months after their 1758 sale and most likely stayed in private collections until 1936 when it appeared in Christie’s London saleroom as part of the Henry Oppenheimer sale. Allaert van Everdingen was an exceptional draughtsman who was particularly skilled at making sets of drawings depicting, with appropriate images and activities, the twelve months of the year.² This tradition was rooted in medieval manuscript illumination, but became increasingly popular in the context of paintings, drawings and prints in the sixteenth century.³ In the seventeenth century, the popularity of such themed sets of images began to wane, and van Everdingen’s devotion to the concept was strikingly unusual. He seems to have made at least eleven sets of drawings of the months, not as one might have imagined, as designs for prints, but as artistic creations in their own right. Six of these sets remain intact, while Davies (see lit.) has reconstructed the others, on the basis of their stylistic and physical characteristics, and clues from the early provenance of the drawings. -

Waterfall in a Wooded Landscape Oil on Canvas 21 X 17½ In

Jacob van Ruisdael (1628 - 1682) Waterfall in a Wooded Landscape oil on canvas 21 x 17½ in. (53.3 x 44.5 cm) signed ca. 1670 Literature: S. Slive, Jacob van Ruisdael. A Complete Catalogue of his Paintings, Drawings and Etchings, (2001), p.161, no.149 Provenance: A. Tischer, Basel; L. Koetser, London, Spring Exhibition, 1968, no.25, repr.; sale, anon. London, Christie’s, 28 June 1974, no. 66 (25,000 gns.); dealer M. Koetser, Zurich; sale, anon. Koln, Lempertz, 12 May 2012, no. 1294, (€195,200) John Mitchell Fine Paintings, London; Asbjorn R. Lunde Collection, New York, 2013. Looking through and beyond a waterfall, a herdsman can be seen fording a river with his sheep in tow. Behind him and to the right is a mature oak within a bosky landscape which gives way to an archetypical Ruisdael sky with receding clouds of varying height and thickness. Flashes of silver and pink suffuse the canopy of clouds as they become darker and more brooding towards the top. To the front and right hand of the picture composition two silver birches rise up over the riverbank. One is a sapling and the other a dying tree which has lost a branch. A flash of sunlight is rippling across the river below as it begins to funnel into the torrent. All round the bank of the river there are clusters of young oak trees clinging on to life. The imaginary mountain in the far left background balances the groups of trees on the right and creates a sense of depth back and beyond the river. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

Swedish Genealogical Societies Have Developed During the Last One Hundred Years

Swedish American Genealogist Volume 5 | Number 4 Article 1 12-1-1985 Full Issue Vol. 5 No. 4 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1985) "Full Issue Vol. 5 No. 4," Swedish American Genealogist: Vol. 5 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/swensonsag/vol5/iss4/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swedish American Genealogist by an authorized editor of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (ISSN 0275-9314) Swedish American Genealo ist A journal devoted to Swedish American biography, genealogy and personal history CONTENTS Genealogical Societies in Sweden Today 141 Two Early Swedes in New York 153 Long Generations 155 "A Second Cousin in Every Corner" 156 Genealogical Queries 167 Literature 169 Index of Personal Names 172 Index of Ships' Names 185 Index of Place Names 186 Vol. V December 1985 No. 4 Swedish America~ eGenealogist Copyright © 1985 Swedish me,rican Genea/og{s1 P.O. Box 2186 Winter Park. FL 32790 (ISS'\ 0275-9.1 l~J Edi1or and Publisher Nil s William Olsson. Ph.D .. F.A.S.G. Con1 rib u1i ng Edilors Glen E. Bro lander, Augustana Coll ege. Rock Island. IL; Sten Carlsson. Ph.D .. Uppsala Uni ve rsit y. Uppsala. Sweden; Henrie Soll be. Norrkopin g. Sweden; Frik Wikcn. Ph .D .. Stockholm. Sweden Contributions are welcomed but the q ua rterly a nd its ed itors assume no res ponsibili ty for errors of fact or views expressed.