This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Ton'don GAZETTE, 14 ^MARCH, ±047

THE tON'DON GAZETTE, 14 ^MARCH, ±047 Council Office. Walter Churchill Hale, O.B.E., M.C., T.D., of Laines, Plumpton. TiOth March, i'1947_ | . The following were this .day appointed to be Warwickshire—Robert Grogvenor Perry, Esq., Sheriffs for the year 1947 : —. ' "C.B.E., of Barton House,'Moreton-in-Marsh, Glos. Westmorland—David Riddell, Esq., of Langbank, ENGLAND Bowness on Windermere. (except Cornwall and Lancashire). Wiltshire—Egbert Cecil Barnes, Esq., of Hunger- Bedfordshire—Major Simon Whitbread, of Southill, down, Seagry, Wilts. near Biggleswade, Beds. Worcestershire—Lieut.-Col. Ernest Charles Lister Berkshire—Sir William Malcolm Mount, Bart., of Bearcroft, of Mere Hall, Hanbury, Droitwich. t- Wasing, Aldermastori. Yorkshire—Captain Christopher Hildyard RjLngrose- Buckinghamshire—Colonel Francis William Watson, Wharton, R.N., of Skelton Castle, Skelton-in- M.C., of Glebe House, Dinton, Aylesbury, Bucks. Cleveland, Saltburn. Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire (Huntingdon- shire Names)—Colonel Ghairles William Dell WALES. Itowe, M.B.E., T.D., of Orton Longueville, near North and South. Peterborough. Anglesey—James Chadwick, Esq., of Haulfre, Cheshire—Colonel Benjamin William Heaton, M.C., Llangoed, Beaumaris, Anglesey. of Hawkswood, Little Budworth, near Tarporley, Breconshire—George Ethelbert Sayce, Esq., of Cheshire. Dinsterwood, Pontrilas, Herefordshire. ^Cumberland—Humphrey Patricius Se'nhouse, Esq., Caernarvonshire—Dr. Emyr Wyn Jones, of Llety'r of The Fitz, Cockermouth. Eos Llanfairtalhaearn and of Seibiant, Pontllyfni. ^Derbyshire—Major Arthur Herbert Betterton, of Cardiganshire—Robert Yates Bickerstaff, Esq., of Hoon Ridge, Hilton, near Derby. Crossways, Grove Avenue, Moseley, Birmingham, Devonshire—John Patrick Hepburn, Esq., of Scot- and of Minyfron, North Road, Aberystwyth. leigh, Chudleigh, Devon. Carmarthenshire—Edgar George Rees, Esq., of Dorsetshire—Lieut.-Co}. -

![Selected Writings of Sir Edward Coke, Vol. II [1606]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2472/selected-writings-of-sir-edward-coke-vol-ii-1606-232472.webp)

Selected Writings of Sir Edward Coke, Vol. II [1606]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Sir Edward Coke, Selected Writings of Sir Edward Coke, vol. II [1606] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Chaucer's Official Life

CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE JAMES ROOT HULBERT CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE Table of Contents CHAUCER'S OFFICIAL LIFE..............................................................................................................................1 JAMES ROOT HULBERT............................................................................................................................2 NOTE.............................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................4 THE ESQUIRES OF THE KING'S HOUSEHOLD...................................................................................................7 THEIR FAMILIES........................................................................................................................................8 APPOINTMENT.........................................................................................................................................12 CLASSIFICATION.....................................................................................................................................13 SERVICES...................................................................................................................................................16 REWARDS..................................................................................................................................................18 -

Speakers of the House of Commons

Parliamentary Information List BRIEFING PAPER 04637a 21 August 2015 Speakers of the House of Commons Speaker Date Constituency Notes Peter de Montfort 1258 − William Trussell 1327 − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Styled 'Procurator' Henry Beaumont 1332 (Mar) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Sir Geoffrey Le Scrope 1332 (Sep) − Appeared as joint spokesman of Lords and Commons. Probably Chief Justice. William Trussell 1340 − William Trussell 1343 − Appeared for the Commons alone. William de Thorpe 1347-1348 − Probably Chief Justice. Baron of the Exchequer, 1352. William de Shareshull 1351-1352 − Probably Chief Justice. Sir Henry Green 1361-1363¹ − Doubtful if he acted as Speaker. All of the above were Presiding Officers rather than Speakers Sir Peter de la Mare 1376 − Sir Thomas Hungerford 1377 (Jan-Mar) Wiltshire The first to be designated Speaker. Sir Peter de la Mare 1377 (Oct-Nov) Herefordshire Sir James Pickering 1378 (Oct-Nov) Westmorland Sir John Guildesborough 1380 Essex Sir Richard Waldegrave 1381-1382 Suffolk Sir James Pickering 1383-1390 Yorkshire During these years the records are defective and this Speaker's service might not have been unbroken. Sir John Bussy 1394-1398 Lincolnshire Beheaded 1399 Sir John Cheyne 1399 (Oct) Gloucestershire Resigned after only two days in office. John Dorewood 1399 (Oct-Nov) Essex Possibly the first lawyer to become Speaker. Sir Arnold Savage 1401(Jan-Mar) Kent Sir Henry Redford 1402 (Oct-Nov) Lincolnshire Sir Arnold Savage 1404 (Jan-Apr) Kent Sir William Sturmy 1404 (Oct-Nov) Devonshire Or Esturmy Sir John Tiptoft 1406 Huntingdonshire Created Baron Tiptoft, 1426. -

Ocm08458220-1808.Pdf (13.45Mb)

1,1>N\1( AACHtVES ** Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of Massachusetts, Boston http://www.archive.org/details/pocketalmanackfo1808amer ; HUSETTS ttttter UnitedStates Calendar; For the Year of our LORD 13 8, the Thirty-fecond of American Independence* CONTAINING . Civil, Ecclrfaflirol, Juiicial, and Military Lids in MASSACHUSE i'TS ; Associations, and Corporate Institutions, tor literary, agricultural, .nd amritablt Purpofes. 4 Lift of Post-Towns in Majfacjufetts, with the the o s s , Names of P r-M a ters, Catalogues of the Officers of the GENERAL GOVERNMENT, its With feveral Departments and Eftabiifhments ; Tunes of jhc Sittings ol the feveral Courts ; Governors in each State ; Public Duties, &c. USEFUL TABLES And a Variety of other intereftiljg Articles. * boston : Publiflied by JOHN WEtT, and MANNING & LORING. Sold, wholesale and retail, at their Book -Stores, CornhUl- P*S# ^ytu^r.-^ryiyn^gw tfj§ : — ECLIPSES for 1808. will eclipfes .his THERE befiv* year ; three of the Sun, and two of the Moon, as follows : • I. The firit will be a total eclipfe of the Moon, on Tuefday morning, May io, which, if clear weather, will be viiible as follows : H. M. Commencement of the eclipfe 1 8^ The beginning or total darknefs 2 6 | Mean The middle of the eciiple - 2 53 )> iimc Ending of total darkneis - 3 40 | morning. "Ending of the eclipfe 4 ^8 J The duration of this is eclipfe 3 hours and 30 minutes ; the duration of total darkneis, 1 hour 34 minutes ; and the cbfcunty i8| digits, in the fouthern half of the earth's (hatiow. -

GIPE-001848-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library III~III~~ mlll~~ I~IIIIIIII~IIIU GlPE-PUNE-OO 1848 CONSTITUTION AL HISTORY OF ENGLAND STUBBS 1Lonbon HENRY FROWDE OXFORD tTNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE AMEN CORNEl!. THE CONSTITUTIONAL mSTORY OF ENGLAND IN ITS ORIGIN AND DEtrLOP~'r BY WILLIAM STUBBS, D.D., BON. LL.D. BISHOP OF CHESTER VOL. III THIRD EDITIOlY @d.orlt AT Tag CLARENDON PRESS J( Deco LXXXIV [ A II rig"'" reserved. ] V'S;LM3 r~ 7. 3 /fyfS CONTENTS. CHAPTER XVIII. LANCASTER AND YORK. 299. Character of the period, p. 3. 300. Plan of the chapter, p. 5. 301. The Revolution of 1399, p. 6. 302. Formal recognition of the new Dynasty, p. 10. 303. Parliament of 1399, p. 15. 304. Conspiracy of the Earls, p. 26. 805. Beginning af difficulties, p. 37. 306. Parliament of 1401, p. 29. 807. Financial and poli tical difficulties, p. 35. 308. Parliament of 1402, 'p. 37. 309. Rebellion of Hotspur, p. 39. 310. Parliament of 14°40 P.42. 311. The Unlearned Parliament, P.47. 312. Rebellion of Northum berland, p. 49. 813. The Long Parliament of 1406, p. 54. 314. Parties fonned at Court, p. 59. 315. Parliament at Gloucester, 14°7, p. 61. 816. Arundel's administration, p. 63. 317. Parlia mont of 1410, p. 65. 318. Administration of Thomae Beaufort, p. 67. 319. Parliament of 14II, p. 68. 820. Death of Henry IV, p. 71. 821. Character of H'!I'l'Y. V, p. 74. 322. Change of ministers, p. 78. 823. Parliament of 1413, p. 79. 324. Sir John Oldcastle, p. 80. 325. -

Tna Prob 11/95/237

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/95/237 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the last will and testament, dated 14 February 1598 and proved 24 April 1600, of Oxford’s half-sister, Katherine de Vere, who died on 17 January 1600, aged about 60. She married Edward Windsor (1532?-1575), 3rd Baron Windsor, sometime between 1553 and 1558. For his will, see TNA PROB 11/57/332. The testatrix’ husband, Edward Windsor, 3rd Baron Windsor, was the nephew of Roger Corbet, a ward of the 13th Earl of Oxford, and uncle of Sir Richard Newport, the owner of a copy of Hall’s Chronicle containing annotations thought to have been made by Shakespeare. The volume was Loan 61 in the British Library until 2007, was subsequently on loan to Lancaster University Library until 2010, and is now in the hands of a trustee, Lady Hesketh. According to the Wikipedia entry for Sir Richard Newport, the annotated Hall’s Chronicle is now at Eton College, Windsor. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Newport_(died_1570) Newport's copy of his chronicle, containing annotations sometimes attributed to William Shakespeare, is now in the Library at Eton College, Windsor. For the annotated Hall’s Chronicle, see also the will of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), TNA PROB 11/53/456; Keen, Alan and Roger Lubbock, The Annotator, (London: Putnam, 1954); and the Annotator page on this website: http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/annotator.html For the will of Roger Corbet, see TNA PROB 11/27/408. -

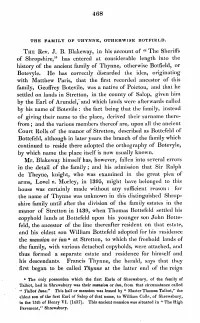

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

Genealogy of the Pepys Family, 1273-1887

liiiiiiiw^^^^^^ UGHAM YOUM; university PROVO, UTAH ^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/genealogyofpepysOOpepy ^P?!pPP^^^ GENEALOGY OF THE PEPYS FAMILY. r GENEALOGY OF THE PEPYS FAMILY 1273— 1887 COMPILED BY WALTER COURTENAY PEPYS LATE LIEUTENANT 60TH ROYAL RIFLES BARRISTER-AT-LAW, LINCOLN'S INN LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS, YORK STREET COVENT GARDEN I 1887 CHISWICK PRESS :—C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT CHANCERY LANE. 90^w^ M ^^1^^^^K^^k&i PREFACE. N offering the present compilation of family data to those interested, I wish it to be clearly understood that I claim to no originality. It is intended—as can readily be seen by those who . read it—to be merely a gathering together of fragments of family history, which has cost me many hours of research, and which I hope may prove useful to any future member of the family who may feel curious to know who his forefathers were. I believe the pedigrees of the family I have compiled from various sources to be the most complete and accurate that ever have been published. Walter Courtenay Pepys. 6l, PORCHESTER TeRRACE, London, W., /uly, 1887. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS. PAGE 1. Arms of the Family, &c. 9 2. First Mention of the Name 1 3. Spelling and Pronunciation of the Name . .12 4. Foreign Form of the Name . 14 5. Sketch of the Family Histoiy 16 6. Distinguished Members of the Family 33 7. Present Members of the Family 49 8. Extracts from a Private Chartulary $2 9. -

Etafforbshite Parish Iregisters Mociety

Bn ( osall. e , B o o k Gen esha l GNOSALL writt n in Domesday e , remains as ) e ( regards its prefix a complete puzzl for philologists . I t s is po sible that the Dome sday scribes blunde red in the ir 1 t h spelling , the early forms of the word ( 2 c e n t ur v ) be ing s Gn o wesh a le t almo t invariably , which la er took on t h esimilar s Gn o usha le t h e pelling of and like , with practically no change k e throughout the c nturies . Th e P AR I S H l t h e inc uded Manors of Gnosall , Walton K i e , n h t le B e fc o t e e [Grang ] , Moreton g y , and Cowl y , Wil h e , t brighton and small estate of Burgh [or Brough] Hall . Domes day Book records close upon 1 0 0 familie s within the se t h e ma nors . Until the close of 1 2 t h century Blymhill was a lso i n e e cluded within Gnosall parish , and until r c nt times th e eastern boundaries by Rul e and Alston seem to have Th e i bee n i ndecisive . mention of Mr . Wh t gr e e v e s Rule s t 1 61 in the Regi ter (Sep , 4) is presumably intended to dis ti n g ui sh the part which lay within the parish . Gnosall township in 1 0 86 only had about half the p o p u lation and o n e quart e r of t h e value of the neighbouring manor s e (and pari h) of Norbury , and compared still l ss favourably ’ with the King s manors of Cowley and B e fc o t e where the t h e bulk of the population live d . -

Download William Jenyns' Ordinary, Pdf, 1341 KB

William Jenyns’ Ordinary An ordinary of arms collated during the reign of Edward III Preliminary edition by Steen Clemmensen from (a) London, College of Arms Jenyn’s Ordinary (b) London, Society of Antiquaries Ms.664/9 roll 26 Foreword 2 Introduction 2 The manuscripts 3 Families with many items 5 Figure 7 William Jenyns’ Ordinary, with comments 8 References 172 Index of names 180 Ordinary of arms 187 © 2008, Steen Clemmensen, Farum, Denmark FOREWORD The various reasons, not least the several german armorials which were suddenly available, the present work on the William Jenyns Ordinary had to be suspended. As the german armorials turned out to demand more time than expected, I felt that my preliminary efforts on this english armorial should be made available, though much of the analysis is still incomplete. Dr. Paul A. Fox, who kindly made his transcription of the Society of Antiquaries manuscript available, is currently working on a series of articles on this armorial, the first of which appeared in 2008. His transcription and the notices in the DBA was the basis of the current draft, which was supplemented and revised by comparison with the manuscripts in College of Arms and the Society of Antiquaries. The the assistance and hospitality of the College of Arms, their archivist Mr. Robert Yorke, and the Society of Antiquaries is gratefully acknowledged. The date of this armorial is uncertain, and avaits further analysis, including an estimation of the extent to which older armorials supplemented contemporary observations. The reader ought not to be surprised of differences in details between Dr.