When Worlds Collide: Federal Construction of State Institutional Competence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attractions Management Issue 2 2015 Photo: Ennead Architects

www.attractionsmanagement.com @attractionsmag VOL20 Q2 2015 www.simworx.co.uk www.attractionsmanagement.com @attractionsmag VOL20 Q2 2015 For full functionality please view in Adobe Reader WARNER BROS STUDIO TOUR EXPANSION BRINGS PLATFORM 9¾ TO LIFE On the cover: Harry Potter star Warwick Davis at the Platform 9¾ launch WORLDS COLLIDE STEPPING UP DISNEY DNA Frank Gehry's Zoos increase Lifelong Imagineer Biomuseo raises the efforts to help Marty Sklar reveals game in Panama animals in the wild Walt's secrets Click here to subscribe to the print edition www.attractionsmanagement.com/subs NWAVE PICTURES DISTRIBUTION PRESENTS WATCH TRAILER AT /nWavePictures GET READY FOR THE DARKEST RIDE NEW WEST COAST USA OFFICE EAST COAST USA OFFICE INTERNATIONAL M 3D I L Janine Baker Jennifer Lee Hackett Goedele Gillis RIDE F +1 818-565-1101 +1 386-256-5151 +32 2 347-63-19 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] DragonMineRide.nWave.com [email protected] | nWave.com | /nWavePicturesDistribution | /nWave nWave® is a registered trademark of nWave Pictures SA/NV - ©2015 nWave Pictures SA/NV - All Rights Reserved presents... NEW nWave.com | /nWavePicturesDistribution | /nWave | /nWave nWave® is a registered trademark of nWave Pictures SA/NV - ©2015 nWave Pictures SA/NV - All Rights Reserved NEW WEST COAST USA OFFICE EAST COAST USA OFFICE INTERNATIONAL Janine Baker Jennifer Lee Hackett Goedele Gillis +1 818-565-1101 +1 386-256-5151 +32 2 347-63-19 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] blog.attractionsmanagement.com PRESERVATION The technology now exists to enable us to scan and preserve the most complex monuments, artefacts and buildings, so they can be reproduced now or in the future. -

Schedule Report

New Releases - 1 October 2021 SAY SOMETHING RECORDS • Available on stunning Red and Black Splatter vinyl (SSR027LP)! A collector's must!! • Featuring: Vocalist Colin Doran of Hundred Reasons, drummer Jason Bowld from Bullet For My Valentine and formerly Pitchshifter, Killing Joke • Full servicing to all relevant media • Extensive print & internet advertising • Print reviews confirmed in KERRANG! and METAL HAMMER • Featured interviews with ‘The Sappenin’ Podcast’ and ‘DJ Force X’ https://open.spotify.com/episode/0ZUhmTBIuFYlgBamhRbPHW?si=9O4x5SWmT2WbhSC0lR3P3g • For fans of: Hundred Reason, Jamie Lenman, Hell is for heroes, The Xcerts, Bullet For My Valentine, Biffy Clyro • Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheyFellFromTheSky Twitter: https://twitter.com/tfftsband Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/tfftsband/ • Soundsphere Magazine: https://www.soundspheremag.com/news/culture/colin-doran-jason-bowld-hundred-reasons-bfmv- pitchshifter-form-rock-studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky/ GigSoup: https://gigsoupmusic.com/pr/colin-doran-jason-bowld-form-rock-studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky-and- release-debut-single-dry/ The AltClub: https://thealtclub.com/they-fell-from-the-sky-release-new-single-dry/ Volatile Weekly: https://volatileweekly.com/2021/03/colin-doran-jason-bowld-hundred-reasons-bfmv-pitchshifter-form-rock- studio-project-they-fell-from-the-sky-and-release-debut-single-dry/ The Punksite: https://thepunksite.com/news/they-fell-from-the-sky-announce-debut-single-and-album/ Tinnitist: https://tinnitist.com/2021/03/22/indie-roundup-23-songs-to-make-monday-far-more-enjoyable/ -

Dec. 2012 $10.95

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

Case Studies in E-Learning Project Management

Plan to Learn: case studies in elearning project management Edited by: Beverly Pasian, M.A. Gary Woodill, Ed.D. © 2006, Canadian eLearning Enterprise Alliance, Beverly Pasian and Gary Woodill, and chapter authors ISBN: 0-9781456-0-7 For additional copies of this publication, please go to: http://www.celea-aceel.ca Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction 1 Beverly Pasian and Gary Woodill Chapter 2 - Literature Review 4 Gary Woodill and Beverly Pasian Developing ePM Skills Chapter 3 - Managing the creation of an online math tutorial 11 for nurses A. Hopkins Chapter 4 - Flexmasters: a unique elearning initiative 17 A. Applebee, D. Veness Chapter 5 - Creating the instructor toolbelt: managing 23 elearning faculty development at a technical community college A. Williams Chapter 6 - Insights from managing a multi-faceted college 32 elearning project K. Siedlaczek, K. Pitts Importance of leadership Chapter 7 - An online food security certificate at the local and 38 international levels R. Malinski, R. McRae Chapter 8 - Going the distance: how an education faculty 47 initiated online professional learning S. Rich, K. Hibbert Chapter 9 - Managing large-scale customized elearning content 51 development B. Soong, W. Chua, N. Kim Hai Chapter 10 - Leading the charge for elearning in British 60 Columbia's high schools R. Labonte Change management Chapter 11 - Communications challenge: migrating "f2f" to 64 elearning C. Kawalilak, R. Corbett Chapter 12 - The Virtual Vermont Residency project 73 L. Williams Chapter 13 - An instructional design model for program 79 management: a case study of the implementation of an online post-degree certificate in special education D. -

2012 Publication

Editor’s Note Dear Artists and Authors, Works of literature, whether whimsical or profound, arise from inspiration, consideration, observation and craft. At times the words flow effortlessly from the pen; occasionally the grip becomes worn and the ink nearly dries before producing works of merit. We call this creative writing. It is a highly coveted skill that makes this journal possible. Clearly, as one can see from perusing page-to-page, the end justifies the means. However, it has occurred to me in a powerful epiphany as I began reading and editing that the true art does not come to completion with publication or press release. No, the true art comes to fruition perennially via you, the reader. We call the process creative writing but the purpose is realized through a creative understanding, a creative interpretation formed from experience and phenomenology. In many ways, much like a piece of paper is a canvas for the writer, the literature itself is a canvas for the readers, on which they plant their own perception and unearth a work of art no other reader can harvest. On each page, a multiplicity of stories thrive, far more than the pages of this journal are capable of containing. Your distinct reading will find something different, an exclusive reflection of yourself both fertilized by and budding from the words in a circular and mutual appreciation. This is the very essence of creative understanding. Now turn the page and begin— reap what you will, experience each story in every way you know how and sow a parcel of yourself in our journal. -

Downloading the Video to Their Device (See Figure 3-63)

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Compositional Possibilities of New Interactive and Immersive Digital Formats A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Program of Composition By Daniel R. Dehaan EVANSTON, IL (June 2019) 2 Abstract From 2008 to 2019, a range of new interactive and immersive digital formats that present new possibilities for musical and artistic expression have become available. In order to begin the work of uncovering what new compositional and experiential possibilities are now possible, this document will examine each format’s core concepts and tools, cataloging the current state of related technologies. It also provides a survey of each format’s representative works, including a discussion of my original and evolving work for virtual reality, Infinite Void. The ultimate goal of this dissertation is to serve as a point of departure for composers interested in working with and influencing the direction that musical and creative expression will take in these immersive and interactive digital environments. 3 Acknowledgments This document would not have been possible without countless individuals to whom I owe more than just the acknowledgements of this page. To my committee members, Chris Mercer, Hans Thomalla, and Stephan Moore, who made themselves available from all corners of the globe and encouraged me to keep going even when it seemed like no end was in sight. To Donna Su, who kept me on track and moving forward throughout my entire time at Northwestern. To my readers, Nick Heinzmann and Caleb Cuzner, without whom I don’t think I would have ever been able to finish. -

Chapter Introduction

Chapter 1: New World Beginnings Chapter Introduction ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning Chapter Introduction I have come to believe that this is a mighty continent which was hitherto unknown. Your Highnesses have an Other World here. Chritopher Columu , 1498 Several billion years ago, that whirling speck of cosmic dust known as the earth, fifth in size among the planets, came into being. About six thousand years ago—only a minute in geological time—recorded history of the Western world began. Certain peoples of the Middle East, developing a written culture, gradually emerged from the haze of the past. Five hundred years ago—only a few seconds figuratively speaking—European explorers stumbled on the Americas. This dramatic accident forever altered the future of both the Old World and the New, and of Africa and Asia as well (see Figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 The Arc of Time © 2016 Cengage Learning Chapter 1: New World Beginnings Chapter Introduction ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning © 2016 Cengage Learning Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may by reproduced or used in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, or in any other manner - without the written permission of the copyright holder. Chapter 1: New World Beginnings: 1.1 The Shaping of North America ® Book Title: The American Pageant: A History of the American People AP Edition Printed By: Valerie Nimeskern ([email protected]) © 2016 Cengage Learning, Cengage Learning 1.1 The Shaping of North America Planet earth took on its present form slowly. -

Kent1258151570.Pdf (651.73

When Two Worlds Collide: The Allied Downgrading Of General Dragoljub “Draža” Mihailović and Their Subsequent Full Support for Josip Broz “Tito” A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Jason Alan Shambach Csehi December, 2009 Thesis written by Jason Alan Shambach Csehi B.A., Kent State University, 2005 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by Solon Victor Papacosma , Advisor Ken Bindas , Chair, Department of History John R. D. Stalvey , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….iv Prelude…………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1…………….………………………………………………………………....11 A Brief Overview of the Existing Literature and an Explanation of Balkan Aspirations Chapter 2.........................................................................................................................32 Churchill’s Yugoslav Policy and British Military Involvement Chapter 3….……………………………………………………………………………70 Roosevelt’s Knowledge and American Military Involvement Chapter 4………………….………………………………………………...………...101 Fallout from the War Postlude….……………………………………………………………….…...…….…131 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………….….142 iii Acknowledgements The completion of this thesis could not have been attained without the help of several key individuals. In particular, my knowledgeable thesis advisor, S. Victor Papacosma, was kind enough to take on this task while looking to be on vacation on a beach somewhere in Greece. Gratitude is also due to my other committee members, Mary Ann Heiss, whose invaluable feedback during a research seminar laid an important cornerstone of this thesis, and Kevin Adams for his participation and valuable input. A rather minor thank you must be rendered to Miss Tanja Petrović, for had I not at one time been well-acquainted with her, the questions of what had happened in the former Yugoslavia during World War II as topics for research seminars would not have arisen. -

When Two Worlds Collide When Two Worlds Collide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Leeds Beckett Repository RUNNING HEAD: When two worlds collide When two worlds collide: A story about collaboration, witnessing and life story research with soldiers returning from war David Carless, PhD and Kitrina Douglas, PhD Leeds Beckett University Forthcoming in Qualitative Inquiry David Carless is a professor of narrative psychology in the Institute of Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure at Leeds Beckett University. Through a range of arts-based, narrative and performative methods, his research explores how identity and mental health are developed, threatened, or recovered in sport and physical activity contexts. Kitrina Douglas is an ambassador for the National Coordinating Centre for Public Engagement (NCCPE), a member of the National Anti-Doping Panel for sport and director of the Boomerang- project.org.uk. Her research at Leeds Beckett University explores identity development, physical activity, and mental health through narrative and arts-informed methodologies. Correspondence: Professor David Carless Institute of Sport, Physical Activity & Leisure Leeds Beckett University Fairfax Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QS, UK [email protected] When two worlds collide 1 Abstract The story we share here stems from our research with British military personnel who are adapting to life with a physical and/or psychological disability after serving in the Iraq or Afghanistan wars. Throughout our research, we have struggled to answer -

Download 2018–2019 Catalogue of New Plays

Catalogue of New Plays 2018–2019 © 2018 Dramatists Play Service, Inc. Dramatists Play Service, Inc. A Letter from the President Dear Subscriber: Take a look at the “New Plays” section of this year’s catalogue. You’ll find plays by former Pulitzer and Tony winners: JUNK, Ayad Akhtar’s fiercely intelligent look at Wall Street shenanigans; Bruce Norris’s 18th century satire THE LOW ROAD; John Patrick Shanley’s hilarious and profane comedy THE PORTUGUESE KID. You’ll find plays by veteran DPS playwrights: Eve Ensler’s devastating monologue about her real-life cancer diagnosis, IN THE BODY OF THE WORLD; Jeffrey Sweet’s KUNSTLER, his look at the radical ’60s lawyer William Kunstler; Beau Willimon’s contemporary Washington comedy THE PARISIAN WOMAN; UNTIL THE FLOOD, Dael Orlandersmith’s clear-eyed examination of the events in Ferguson, Missouri; RELATIVITY, Mark St. Germain’s play about a little-known event in the life of Einstein. But you’ll also find plays by very new playwrights, some of whom have never been published before: Jiréh Breon Holder’s TOO HEAVY FOR YOUR POCKET, set during the early years of the civil rights movement, shows the complexity of choosing to fight for one’s beliefs or protect one’s family; Chisa Hutchinson’s SOMEBODY’S DAUGHTER deals with the gendered differences and difficulties in coming of age as an Asian-American girl; Melinda Lopez’s MALA, a wry dramatic monologue from a woman with an aging parent; Caroline V. McGraw’s ULTIMATE BEAUTY BIBLE, about young women trying to navigate the urban jungle and their own self-worth while working in a billion-dollar industry founded on picking appearances apart. -

Dragon Magazine #238

The Halls of Amusement ack in the distant days of middle school, Greg was one of treasure was so good that we didn’t complain. Until we my first players to take a turn behind the DM’s screen. We reached the central chamber. were all eager to see what he’d do, and I couldn’t wait to play The place was huge, with a raised platform in the center. my own characters, a min-maxed high elf fighter/magic-user The walls were covered in black flock, and the floor was tiled named Windrhymer the White and an even more min-maxed with some weird glowing material that changed patterns. fighter/magic-user/thief half-drow named Ralph the Rogue. When Greg pointed out the spinning mirror-balls on the ceiling (Yes, I’m still embarrassed about it all.) All we knew for sure we became nervous. When he described the huge black was that Greg had drawn all over a ream and a half of graph dragon wearing the white leisure suit, dancing upon the high paper. He called the dungeon “The Halls of Amusement.” platform; we realized he had gone way too far. My elves had pals, naturally. Tom played a pair of fighters “The Disco Dragon!” someone cried. We fell over each other named Harry and Burt, or something equally English. Someone to kill the beast, not so much for fear of our lives, but because else was stuck with the cleric and another character. While the even at that age we realized that a reptilian John Travolta was PCs didn’t find a lasting place in my memory, certain moments an abomination that must be destroyed. -

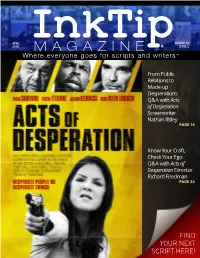

M a G a Z I N

APRIL VOLUME 19 2019 MAGAZINE ® ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers™ From Public Relations to Made-up Desperations: Q&A with Acts of Desperation Screenwriter Nathan Illsley PAGE 16 Know Your Craft, Check Your Ego: Q&A with Acts of Desperation Director Richard Friedman PAGE 30 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! CONTENTS Contest/Festival Winners 4 FIND YOUR Feature Scripts – SCRIPTS FAST Grouped by Genre ON INKTIP! 5 From Public Relations to Made-up Desperations: Q&A with Acts of Desperation Screenwriter Nathan Illsley INKTIP OFFERS: 16 • Listings of Scripts and Writers Updated Daily • Mandates Catered to Your Needs • Newsletters of the Latest Scripts and Writers Know Your Craft, Check Your Ego: Q&A with • Personalized Customer Service Acts of Desperation Director • Comprehensive Film Commissions Directory Richard Friedman 30 Scripts Represented by Agents/Managers 43 Teleplays You will find what you need on InkTip Sign up at InkTip.com! 44 Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they place their scripts on our site. 3 WHAT PEOPLE SAY ABOUT INKTIP WRITERS “[InkTip] was the resource that connected “Without InkTip, I wouldn’t be a produced a director/producer with my screenplay screenwriter. I’d like to think I’d have – and quite quickly. I HAVE BEEN gotten there eventually, but INKTIP ABSOLUTELY DELIGHTED CERTAINLY MADE IT HAPPEN WITH THE SUPPORT AND FASTER … InkTip puts screenwriters into OPPORTUNITIES I’ve gotten through contact with working producers.” being associated with InkTip.” – ANN KIMBROUGH, GOOD KID/BAD KID – DENNIS BUSH, LOVE OR WHATEVER “InkTip gave me the access that I needed “There is nobody out there doing more to directors that I BELIEVE ARE for writers than InkTip – nobody.