Community Board 10 Comprehensive Preservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARKS and RECREATION COMMITTEE MINUTES For

PARKS AND RECREATION COMMITTEE MINUTES Wednesday, April 14th, 2021, 6:30 pm Hon. Karen Horry, Chair Meeting began at 6:30 pm and was held via Zoom link. The meeting was chaired by Hon. Karen Horry, Committee Chair. Committee Members in Attendance: Chair, Hon. Karen Horry, Hon. Barbara Nelson, Hon. Marcus Wilson, Hon. Terri Wisdom, Hon. Karen Dixon, Hon. Derek Perkinson, Hon. Tahanie Aboushi and Hon. Nadine Pinkett Committee Members Absent: Hon. Kevin Bitterman and Hon. Deborah Gilliard Board Members Present: - Board Chair Hon. Cecily Harris and Hon. Donna Gill Board Chair: Hon. Cicely Harris District Office: District Manager the the Shatic Mitchell, Jasmin Heatley (Community Assistant) Guests in attendance: Ambassador Sujay, Velma G., Jose’s IPad, Abena Smith (President, 32nd Precinct Community Council), Gregory Baggett (A. Phillip Randolph Neighborhood Alliance), Minah Whyte (Assemblyman Al Taylor), Dara Harris (Honeys and Bears), Zakiyah DeGraffe (Hansborough Recreation Center), Aarian Punter, Allen Black, Amelia A. Montgomery, Carol Martin, Cassandra Polite, Dolina Duzant, Georgia Dawson, Harriet Addamo, Jamie Baez, Jane’s IPad, Jeanne Nedd, Jana LaSorte (NYC Parks Administrator Harlem Historic Parks), John Hession, Joyce Adewumi (NY African Chorus Ensemble/NYC Multicultural Festival), Maleta Apogo (Community Resident), Vernon Ballard (A. Phillip Randolph Neighborhood Alliance), Shena Kaufman (Parks Manager District 10 & 11), Chris Noel (Community Member i-Phone), Shamier Settle (A. Phillip Randolph Neighborhood Alliance), Mary Williams, Richard Cox, Richard Williams, Robert McCullough (Each One Teach One Rucker Pro Legend), Samuel White, Jr., Rajab safi, Moto z3, Tiffany Foster, Walter Gilroy, Veronica Cook, SANAB, Mary Vinson, Yvonne Stanford, Allen Black, Aarian Punter and Ysabel Abreu. -

Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-9-2017 The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 Allyson Compton CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/166 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 by Allyson Compton Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: April 10, 2017 Kellie Carter Jackson Date Signature April 10, 2017 Jonathan Rosenberg Date Signature of Second Reader Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Public Space and the Genesis of Black Harlem ................................................. 7 Defining Public Space ................................................................................................... 7 Defining Race Riot ....................................................................................................... 9 Why Harlem? ............................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2: Setting -

Where Stars Are Born and Legends Are Made™

Where Stars are Born and Legends are Made™ The Apollo Theater Study Guide is published by the Education Program of the Apollo Theater in New York, NY | Volume 2, Issue 1, November 2010 If the Apollo Theater could talk, imagine the stories it could tell. It The has witnessed a lot of history, and seen a century’s worth of excitement. The theater itself has stood proudly on 125th Street since 1914, when it started life as a burlesque house for whites only, Hurtig & Seamon’s New Burlesque Theater. Dancers in skimpy costumes stripped down to flesh-colored leotards, and comics told bawdy jokes – that is, until then New York City Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia made the decision to close down burlesque houses all over the city. When the doors of the burlesque theaters were padlocked, the building was sold. By S ul the time it reopened in 1934, a new name proclaimed itself from the marquee: the 125th Street Apollo Theatre. From the start, the Apollo was beloved by Harlemites, and immediately of became an integral part of Harlem life. When the Apollo first opened, Harlem boasted a lot of theaters and clubs. But many didn’t admit black audiences. Though the musicians who played in the clubs were black, the audiences were often white; the country still had a lot to American learn about integration. But the Apollo didn’t play primarily to whites. As soon as it opened its doors, black residents of Harlem streamed in themselves to enjoy the show. In the early years, the Apollo presented acts in a revue format, with a variety of acts on each bill. -

The Sloat Family

THE SLOAT FAMILY We are indebted to Mr. John Drake Sloat of St. Louis, Missouri, for the Sloat family data. We spent many years searching original unpublished church and court records. Mr. Sloat assembled this material on several large charts, beautifully executed and copies are on file at the New York Public Library. It was from copies of Mr. Sloat's charts that this book of Sloat Mss was assembled. from Charts made by John Drake Sloat [#500 below] Assembled by May Hart Smith {1941}[no date on LA Mss – must be earlier] Ontario, California. [begin transcriber notes: I have used two different copies of the original Mss. to compile this version. The first is a xerographic copy of the book in the Los Angeles Public Library (R929.2 S6338). The second, which is basically the same in the genealogy portion, but having slightly different introductory pages, is a print from the microfilm copy of the book in the Library of Congress. The main text is from the LA Library copy, with differences in the microfilm copy noted in {braces}. Notes in [brackets] are my notes. Note that the comparison is not guaranteed to be complete. As noted on the appropriate page, I have also converted the Roman numerals used for 'unconnected SLOATs' in the original Mss., replacing them with sequential numbers starting with 800 – to follow the format of Mrs. Smith in the rest of her Mss. I have also expanded where the original listed two, or sometimes even three, generations under one entry, instead using the consistent format of one family group per listing. -

Morningside Heights Upper West Side Central Park

Neighborhood Map ¯ Manhattanville Salem United 601 Junior High School 499 431 429 401 305 299 Methodist Church 199 101 99 1 555 W 129 Street W 129 Street W 129 Street W 129 Street Harlem Village Manhattanville National Jazz Museum Green 556 Health Center St. Nicholas in Harlem Edward P. Bowman 2168 3219 Sheltering Arms 30 29 25 Park 368 369 Broadway 601 2401 2406 Amsterdam Bus Depot 2094 3200 Playground Park Rev. Linnette C. Williamson Metropolitan Church of Memorial Park St. Nicholas Baptist Church Jesus Christ of Collyer Brothers 401 Unity Park 12 439 399 301 Playground South 101 Latter-day Saints Park W 126 Street 567 11 St. Nicholas Houses Amsterdam Avenue Amsterdam W 128 Street W 128 Street W 128 Street Convent Avenue St. Nicholas Avenue Old Broadway Blvd Douglass Frederick 559 M2 1361 14 LTD M2 3181 M3 499 M10 LTD 5 6 Maysles 2066 M3 M10 348 M2 Documentary 2160 M2 St. Andrew’s 1 Center 125 St Bx15 Episcopal Church M104 M101 299 201 W 125 StreetBx15 LTD 401 399 363 357 349 301 199 101 99 1 LTD Terrace Nicholas St. M101 W 127 Street W 127 Street W 127 Street M11 LTD Bx15 M100 M104 Bx15 M101 439 LTD M11 04 1 501 M100 M M101 M7 M104 M104 M102 M7 167 166 327 332 2130 2133 2358 2359 Clayton M102 2050 George Bruce 499 3170 William B. Williams 8 Avenue 8 Library Avenue 5 Washington Community Avenue Lenox 401 399 349 Garden Garden 299 201 199 101 99 1 Malcolm X Boulevard W 126 Street W 126 Street W 126 Street Broadway General Grant Houses Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. -

LEGEND Location of Facilities on NOAA/NYSDOT Mapping

(! Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 2 Page 45 of 50 St. Paul's Episcopal Church and Rectory Downtown Ossining Historic District Highland Cottage (Squire House) Rockland Lake (!304 Old Croton Aqueduct Stevens, H.R., House inholding All Saints Episcopal Church Complex (Church) Jug Tavern All Saints Episcopal Church (Rectory/Old Parish Hall) (!305 Hook Mountain Rockland Lake Scarborough Historic District (!306 LEGEND Nyack Beach Underwater Route Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CP Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CSX Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve (!307 Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve NYS Canal System, Underground (! Rockefeller Park Preserve Milepost Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve )" Sherman Creek Substation Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Methodist Episcopal Church at Nyack *# Yonkers Converter Station Rockefeller Park Preserve Upper Nyack Firehouse ^ Mine Rockefeller Park Preserve Van Houten's Landing Historic District (!308 Park Rockefeller Park Preserve Union Church of Pocantico Hills State Park Hopper, Edward, Birthplace and Boyhood Home Philipse Manor Railroad Station Untouched Wilderness Dutch Reformed Church Rockefeller, John D., Estate Historic Site Tappan Zee Playhouse Philipsburg Manor St. Paul's United Methodist Church US Post Office--Nyack Scenic Area Ross-Hand Mansion McCullers, Carson, House Tarrytown Lighthouse (!309 Harden, Edward, Mansion Patriot's Park Foster Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church Irving, Washington, High School Music Hall North Grove Street Historic District DATA SOURCES: NYS DOT, ESRI, NOAA, TDI, TRC, NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF Christ Episcopal Church Blauvelt Wayside Chapel (Former) First Baptist Church and Rectory ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION (NYDEC), NEW YORK STATE OFFICE OF PARKS RECREATION AND HISTORICAL PRESERVATION (OPRHP) Old Croton Aqueduct Old Croton Aqueduct NOTES: (!310 1. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

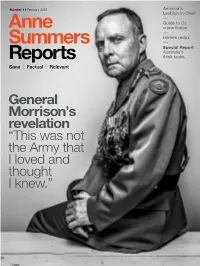

2015 Anne Summers Issue 11 2015

Number 11 February 2015 America’s Lesbian-in-Chief Guide to Oz crime fiction Harlem redux Special Report Australia’s think tanks Sane Factual Relevant General Morrison’s revelation “This was not the Army that I loved and thought I knew.” #11 February 2015 I HOPE YOU ENJOY our first issue for 2015, and our eleventh since we started our digital voyage just over two years ago. We introduce Explore, a new section dealing with ideas, science, social issues and movements, and travel, a topic many of you said, via our readers’ survey late last year, you wanted us to cover. (Read the full results of the survey on page 85.) I am so pleased to be able to welcome to our pages the exceptional mrandmrsamos, the husband-and-wife team of writer Lee Tulloch and photographer Tony Amos, whose piece on the Harlem revival is just a taste of the treats that lie ahead. No ordinary travel writing, I can assure you. Anne Summers We are very proud to publish our first investigative special EDITOR & PUBLISHER report on Australia’s think tanks. Who are they? Who runs them? Who funds them? How accountable are they and how Stephen Clark much influence do they really have? In this landmark piece ART DIRECTOR of reporting, Robert Milliken uncovers how thinks tanks are Foong Ling Kong increasingly setting the agenda for the government. MANAGING EDITOR In other reports, you will meet Merryn Johns, the Australian woman making a splash as a magazine editor Wendy Farley in New York and who happens to be known as America’s Get Anne Summers DESIGNER Lesbian-in-Chief. -

Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report

Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report September 2015 Cover Photograph: 133 to 143 West 122nd Street Christopher D. Brazee, September 2015 Mount Morris Park Historic District Extension Designation Report Essay Researched and Written by Theresa C. Noonan and Tara Harrison Building Profiles Prepared by Tara Harrison, Theresa C. Noonan, and Donald G. Presa Architects’ Appendix Researched and Written by Donald G. Presa Edited by Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research Photographs by Christopher D. Brazee Map by Daniel Heinz Watts Commissioners Meenakshi Srinivasan, Chair Frederick Bland John Gustafsson Diana Chapin Adi Shamir-Baron Wellington Chen Kim Vauss Michael Devonshire Roberta Washington Michael Goldblum Sarah Carroll, Executive Director Mark Silberman, Counsel Jared Knowles, Director of Preservation Lisa Kersavage, Director of Special Projects and Strategic Planning TABLE OF CONTENTS MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION MAP .................... AFTER CONTENTS TESTIMONY AT THE PUBLIC HEARING .............................................................................................. 1 MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION BOUNDARIES .................................... 1 SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 3 THE HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE MOUNT MORRIS PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT EXTENSION Early History and Development of the Area ................................................................................ -

Youth Theater

15_144398 bindex.qxp 7/25/07 7:39 PM Page 390 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX African Paradise, 314 Anthropologie, 325 A Hospitality Company, 112 Antiques and collectibles, AIDSinfo, 29 318–319 AARP, 52 AirAmbulanceCard.com, 51 Triple Pier Antiques Show, ABC Carpet & Home, 309–310, Airfares, 38–39 31, 36 313–314 Airlines, 37–38 Apartment rentals, 112–113 Above and Beyond Tours, 52 Airports, 37 Apollo Theater, 355–356 Abyssinian Baptist Church, getting into town from, 39 Apple Core Hotels, 111 265–266 security measures, 41 The Apple Store, 330 Academy Records & CDs, 338 Air-Ride, 39 Architecture, 15–26 Access-Able Travel Source, 51 Air Tickets Direct, 38 Art Deco, 24–25 Access America, 48 Air tours, 280 Art Moderne, 25 Accessible Journeys, 51 AirTrain, 42–43 Beaux Arts, 23 Accommodations, 109–154. AirTran, 37 best structures, 7 See also Accommodations Alexander and Bonin, 255 early skyscraper, 21–22 Index Alice in Wonderland (Central Federal, 16, 18 bedbugs, 116 Park), 270 Georgian, 15–16 best, 9–11 Allan & Suzi, 327 Gothic Revival, 19–20 chains, 111 Allen Room, 358 Greek Revival, 18 Chelsea, 122–123 All State Cafe, 384 highlights, 260–265 family-friendly, 139 Allstate limousines, 41 International Style, 23–24 Greenwich Village and the Alphabet City, 82 Italianate, 20–21 Meat-Packing District, Alphaville, 318 late 19th century, 20 119–122 Amato Opera Theatre, 352 Postmodern, 26 Midtown East and Murray American Airlines, 37 Second Renaissance Revival, Hill, 140–148 American Airlines Vacations, 57 -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

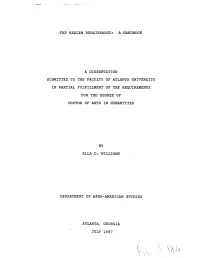

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study.