Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negroes Are Different in Dixie: the Press, Perception, and Negro League Baseball in the Jim Crow South, 1932 by Thomas Aiello Research Essay ______

NEGROES ARE DIFFERENT IN DIXIE: THE PRESS, PERCEPTION, AND NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH, 1932 BY THOMAS AIELLO RESEARCH ESSAY ______________________________________________ “Only in a Negro newspaper can a complete coverage of ALL news effecting or involving Negroes be found,” argued a Southern Newspaper Syndicate advertisement. “The good that Negroes do is published in addition to the bad, for only by printing everything fit to read can a correct impression of the Negroes in any community be found.”1 Another argued that, “When it comes to Negro newspapers you can’t measure Birmingham or Atlanta or Memphis Negroes by a New York or Chicago Negro yardstick.” In a brief section titled “Negroes Are Different in Dixie,” the Syndicate’s evaluation of the Southern and Northern black newspaper readers was telling: Northern Negroes may ordain it indecent to read a Negro newspaper more than once a week—but the Southern Negro is more consolidated. Necessity has occasioned this condition. Most Southern white newspapers exclude Negro items except where they are infamous or of a marked ridiculous trend… While his northern brother is busily engaged in ‘getting white’ and ruining racial consciousness, the Southerner has become more closely knit.2 The advertisement was designed to announce and justify the Atlanta World’s reformulation as the Atlanta Daily World, making it the first African-American daily. This fact alone probably explains the advertisement’s “indecent” comment, but its “necessity” argument seems far more legitimate.3 For example, the 1932 Monroe Morning World, a white daily from Monroe, Louisiana, provided coverage of the black community related almost entirely to crime and church meetings. -

History of the Development of the ICD

History of the development of the ICD 1. Early history Sir George Knibbs, the eminent Australian statistician, credited François Bossier de Lacroix (1706-1777), better known as Sauvages, with the first attempt to classify diseases systematically (10). Sauvages' comprehensive treatise was published under the title Nosologia methodica. A contemporary of Sauvages was the great methodologist Linnaeus (1707-1778), one of whose treatises was entitled Genera morborum. At the beginning of the 19th century, the classification of disease in most general use was one by William Cullen (1710-1790), of Edinburgh, which was published in 1785 under the title Synopsis nosologiae methodicae. For all practical purposes, however, the statistical study of disease began a century earlier with the work of John Graunt on the London Bills of Mortality. The kind of classification envisaged by this pioneer is exemplified by his attempt to estimate the proportion of liveborn children who died before reaching the age of six years, no records of age at death being available. He took all deaths classed as thrush, convulsions, rickets, teeth and worms, abortives, chrysomes, infants, livergrown, and overlaid and added to them half the deaths classed as smallpox, swinepox, measles, and worms without convulsions. Despite the crudity of this classification his estimate of a 36 % mortality before the age of six years appears from later evidence to have been a good one. While three centuries have contributed something to the scientific accuracy of disease classification, there are many who doubt the usefulness of attempts to compile statistics of disease, or even causes of death, because of the difficulties of classification. -

The Sloat Family

THE SLOAT FAMILY We are indebted to Mr. John Drake Sloat of St. Louis, Missouri, for the Sloat family data. We spent many years searching original unpublished church and court records. Mr. Sloat assembled this material on several large charts, beautifully executed and copies are on file at the New York Public Library. It was from copies of Mr. Sloat's charts that this book of Sloat Mss was assembled. from Charts made by John Drake Sloat [#500 below] Assembled by May Hart Smith {1941}[no date on LA Mss – must be earlier] Ontario, California. [begin transcriber notes: I have used two different copies of the original Mss. to compile this version. The first is a xerographic copy of the book in the Los Angeles Public Library (R929.2 S6338). The second, which is basically the same in the genealogy portion, but having slightly different introductory pages, is a print from the microfilm copy of the book in the Library of Congress. The main text is from the LA Library copy, with differences in the microfilm copy noted in {braces}. Notes in [brackets] are my notes. Note that the comparison is not guaranteed to be complete. As noted on the appropriate page, I have also converted the Roman numerals used for 'unconnected SLOATs' in the original Mss., replacing them with sequential numbers starting with 800 – to follow the format of Mrs. Smith in the rest of her Mss. I have also expanded where the original listed two, or sometimes even three, generations under one entry, instead using the consistent format of one family group per listing. -

LEGEND Location of Facilities on NOAA/NYSDOT Mapping

(! Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 2 Page 45 of 50 St. Paul's Episcopal Church and Rectory Downtown Ossining Historic District Highland Cottage (Squire House) Rockland Lake (!304 Old Croton Aqueduct Stevens, H.R., House inholding All Saints Episcopal Church Complex (Church) Jug Tavern All Saints Episcopal Church (Rectory/Old Parish Hall) (!305 Hook Mountain Rockland Lake Scarborough Historic District (!306 LEGEND Nyack Beach Underwater Route Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CP Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CSX Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve (!307 Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve NYS Canal System, Underground (! Rockefeller Park Preserve Milepost Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve )" Sherman Creek Substation Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Methodist Episcopal Church at Nyack *# Yonkers Converter Station Rockefeller Park Preserve Upper Nyack Firehouse ^ Mine Rockefeller Park Preserve Van Houten's Landing Historic District (!308 Park Rockefeller Park Preserve Union Church of Pocantico Hills State Park Hopper, Edward, Birthplace and Boyhood Home Philipse Manor Railroad Station Untouched Wilderness Dutch Reformed Church Rockefeller, John D., Estate Historic Site Tappan Zee Playhouse Philipsburg Manor St. Paul's United Methodist Church US Post Office--Nyack Scenic Area Ross-Hand Mansion McCullers, Carson, House Tarrytown Lighthouse (!309 Harden, Edward, Mansion Patriot's Park Foster Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church Irving, Washington, High School Music Hall North Grove Street Historic District DATA SOURCES: NYS DOT, ESRI, NOAA, TDI, TRC, NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF Christ Episcopal Church Blauvelt Wayside Chapel (Former) First Baptist Church and Rectory ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION (NYDEC), NEW YORK STATE OFFICE OF PARKS RECREATION AND HISTORICAL PRESERVATION (OPRHP) Old Croton Aqueduct Old Croton Aqueduct NOTES: (!310 1. -

SELF-IPIEREST and SOCIAL CONTROL: Uitlandeet Rulx of JOHANNESBURG, 1900-1901

SELF-IPIEREST AND SOCIAL CONTROL: UITLANDEEt RUlX OF JOHANNESBURG, 1900-1901 by Diana R. MacLaren Good government .. [means] equal rights and no privilege .. , a fair field and no favour. (1) A. MacFarlane, Chairman, Fordsburg Branch, South African League. At the end of May 1900 the British axmy moved into Johannesburg and Commandant F. E. T. Krause handed over the reins of government to Col. Colin MacKenzie, the new Military Governor of the Witwatersrand. But MacKenzie could not rule alone, and his superior, Lord Roberts, had previously agreed with High Commissioner Milner that MacKenzie would have access to civilian advisers who, being Randites for the most past, could offer to his administration their knowledge of local affairs. So, up from the coast and the Orange Free State came his advisers: inter alia, W. F. Monypenny, previously editor of the jingoist Johannesburg-; Douglas Forster, past President of the Transvaal Branch of the South African League (SAL); Samuel Evans, an Eckstein & CO employee and informal adviser to Milner; and W. Wybergh, another past President of the SAL and an ex-employee of Consolidated Gold Fields. These men and the others who served MacKenzie as civilian aides had been active in Rand politics previous to the war and had led the agitation for reform - both political and economic - which had resulted in war. Many had links with the minbg industry, either as employees of large firms or as suppliers of machinery, while the rest were in business or were professional men, generally lawyers. It was these men who, along with J. P. Fitzpatrick, had engineered the unrest, who formulated petitions, organized demonstrations and who channelled to Milner the grist for his political mill. -

Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964

Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964 Mandi Isaacs Jackson Housing Access On December 30,1963, photographers patiently awaited the arrival of ten ants from two Harlem tenements scheduled to appear in Manhattan Civil Court on charges of rent non-payment. Since the chilly early morning hours, photog raphers had mulled around outside the civil courthouse on Centre Street, mov ing cameras from one shoulder to the other, lighting and extinguishing ciga rettes. The press had been tipped off by strike leaders that they would smuggle dead rats into the courtroom to serve as both symbol and evidence of what the media liked to call their "sub-human" living conditions. These defendants rep resented thirteen families on 117th Street who had been withholding rent in protest of the their buildings' combined 129 building violations, pointing to "dark and littered" hallways, "crumbly" ceilings, and broken windows, water, and heat. But what photographers waited to capture in black and white were the "rats as big as cats" that plagued the dilapidated buildings. "They so big they can open up your refrigerator without you!" reported one tenant.1 Finally, at 11:30 am, the tenants waded through the river of television and newspaper cameras and removed three dead rodents from a milk container, a paper bag, and a newspaper. Flash bulbs exploded. As he displayed the enor mous dead rat he had brought from home, tenant William D. Anderson told a New York Amsterdam News reporter, "This is the only way to get action from 0026-3079/2006/4701-053S2.50/0 American Studies, 47:1 (Spring 2006): 53-79 53 54 Mandi Isaacs Jackson the property owners who don't care anything about the tenants."2 The grotesque statement made by the rat-brandishing rent strikers was, as William Anderson told the reporters, an eleventh-hour stab at the visibility tenants were consis tently denied. -

Finding and Using African American Newspapers

Finding and Using African American Newspapers Timothy N. Pinnick [email protected] http://blackcoalminerheritage.net/ INTRODUCTION African American researchers will find black newspapers an extremely valuable part of their search strategy. Although mainstream newspapers should always be consulted, African American newspapers will provide nuggets of information that can be found nowhere else. Although the first African American newspaper was established in 1827, it is in the post Civil War period that the black press experienced tremendous growth. Hundreds of newspapers appeared to quench the thirst for knowledge in the newly freed slaves, and to provide an accurate and positive image of the race. Clint C. Wilson took the incomplete manuscript of the foremost historian of the African American press, Armistead Pride and produced A History of the Black Press in 1997. It is a great source of information on black newspapers. Another worthwhile source can be found online at the public television website of PBS. They produced the documentary film, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords” in 1999, and their website is rich in reference material. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/index.html VALUE OF BLACK NEWSPAPERS Aside from the most obvious benefit of locating obituaries, researchers can discover: an exact or nearly exact event date (birth, death, or marriage) of an ancestor, therefore enhancing the odds of a successful outcome when the eventual request for the vital record is made. Remember, some places will only search a short span of years in their index, and charge you whether they find the record or not. additional information on the event that will not be found on the vital record. -

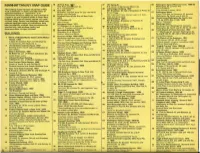

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900

07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 1 11/19/08 12:53:03 PM 07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 2 11/19/08 12:53:04 PM The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900 prepared by LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory This essay reflects the views of the author alone and does not necessarily imply concurrence by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) or any other organization or agency, public or private. About the Author LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D., is on the Principal Professional Staff of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the Strategic Assessments Office of the National Security Analysis Department. He retired from a 24-year career in the Army after serving as an infantry officer and war planner and is a veteran of Operation Desert Storm. Dr. Leonhard is the author of The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle (1991), Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (1994), The Principles of War for the Informa- tion Age (1998), and The Evolution of Strategy in the Global War on Terrorism (2005), as well as numerous articles and essays on national security issues. Foreign Concessions and Spheres of Influence China, 1900 Introduction The summer of 1900 saw the formation of a perfect storm of conflict over the northern provinces of China. Atop an anachronistic and arrogant national government sat an aged and devious woman—the Empress Dowager Tsu Hsi. -

Bloomingdale: Colonial Times and After the Revolutionary War by Pam Tice, Member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group Planning Committee

===================================================================== RNA House History Club May 2021 ===================================================================== [The following post is the first of three documenting life in the Bloomingdale neighborhood in the colonial and revolutionary times. It can be seen on the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group blog site at: https://www.upperwestsidehistory.org/blog/march-30th-2021] Part 1: Bloomingdale: Colonial Times and after the Revolutionary War by Pam Tice, Member of the Bloomingdale Neighborhood History Group planning committee Introduction A few months ago, a new website developed by John Jay College caught my attention. Like many institutions of higher education, the College was exploring the link between slavery and the famous man whose name adorns it. One of the resources used was the 1790 federal Census. I looked up Charles Ward Apthorp, whom I had written about previously, one of the colonial property owners in our Bloomingdale neighborhood. He owned eight slaves. That got me thinking: who were the other people in this census? How was the Bloomingdale neighborhood settled in the era before the Revolution? What was Bloomingdale like after the Revolution and in the early 1800s? I started to dig a bit deeper into the Bloomingdale history, beyond the work of numerous local historians who write about a particular property owner and the history of a mansion house, as I myself had done in writing about Apthorp’s mansion that became Elm Park. The Bloomingdale Road, authorized in 1703, and laid out in 1707, was key to the area’s development; Bloomingdale became more like a suburb of the city than what we call a neighborhood today. -

DUNBAR APARTMENTS, I 49Th Street to I 50Th Street, Beh.Rcon 7Th Avenue and 8Th Avenue, Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission July 14, 1970, Number 4 LP-0708 DUNBAR APARTMENTS, I 49th Street to I 50th Street, beh.rcon 7th Avenue and 8th Avenue, Borough of Manhattan. Begun 1926, completed 1928.; architect Andrew J. Thomas. Landmark Site: Borough of ~~anhattan Tax t~ap Block 2035, Lot I. On May 26, 1970, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Dunbar Apartments and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. (Item No. 28). The hearing had been duly advertised In accordance with the provisions of law. One witness spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. The City's Landmarks Preservation program has been discussed with the owners of the Dunbar Apartments, and they have indicated that they have no objection to the proposed designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Dunbar Apartments, named after the famous Black poet of the turn of the century, Paul Lawrence Dunbar (1872-1906), occupies the entire block bounded by 149th and !50th Streets and Seventh and Eighth Avenues. It was the first large cooperative built for Blacks and was Manhattan's earliest large garden apartment complex. Financed by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and designed by the architect Andrew J. Thomas, the building was completed in 1928 and was destined, from the planning and sociological points of view, to occupy a pivotal place in the history of the Harlem community. The complex consists of six independent U-shaped bui !dings, containing 51 I apartments, and is clustered around a large interior garden court.