'Silent Arrival': the Second Wave of the Great Migration and Its Affects on Black New York, 1940-1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Hill Ymca Winter/Spring 2020 We Are Y

NEW! CUSTOMIZE YOUR MEMBERSHIP! See Inside for Details WE ARE Y PROGRAM & CLASS GUIDE CASTLE HILL YMCA WINTER/SPRING 2020 2 Castle Hill Avenue Bronx, NY 10473 212-912-2490 ymcanyc.org/castlehill WHY THE Y NO HIDDEN FEES • NO ANNUAL FEES • NO PROCESSING FEES • NO CONTRACTS ADULT/SENIOR FAMILY AMENITIES, PROGRAMS, AND CLASSES MEMBERSHIP MEMBERSHIP Member discounts and priority registration l l State-of-the-art fitness center l l Over 60 FREE weekly group exercise classes l l FREE YMCA Weight Loss Program l l Y Fit Start (FREE 12-week fitness program) l l One Indoor & Two Outdoor Swimming Pools l l Sauna l l Basketball court l l FREE Parking Lot l l FREE WiFi l l Customizable Family & Household Memberships l FREE family classes l FREE teen orientation to the fitness center l FREE teen programs l Convenient family locker room l FREE Child Watch l 212-912-2490 ymcanyc.org/castlehill @bronxymca facebook.com/bronxymca @bronxymca TABLE OF CONTENTS ADULTS ................................ 4 KIDS & FAMILY (AGES 0-4) .... 8 YOUTH (AGES 5-12) ............ 10 TEENS (AGES 12-17) ........... 14 SWIM .................................. 16 SUMMER CAMP .................. 22 EVENTS/RENTALS .............. 26 JOIN THE Y .......................... 30 Dear Castle Hill YMCA Member, LOCATIONS ........................ 35 Welcome to another exciting year at the YMCA of Greater New York! We look forward to serving you and your family with a variety of wonderful programs in 2020! HOURS OF OPERATION OPEN 364 DAYS A YEAR The New Year is my favorite time of year. It’s an opportunity to reflect, refresh, and reset. If you want to try something new in Monday - Friday: 5:30 AM - 10:00 PM 2020, we have a world of options. -

Globalization & Crime

Franko-3604-Prelims.qxd 9/19/2007 12:19 PM Page i Globalization & Crime Franko-3604-Prelims.qxd 9/19/2007 12:19 PM Page ii Key Approaches to Criminology The Key Approaches to Criminology series celebrates the removal of traditional barriers between disciplines and brings together some of the leading scholars working at the intersections of different but related fields. Each book in the series aids readers in making intellectual connections across subjects, and highlights the importance of studying crime, criminalization, justice, and punishment within a broad context. The intention, then, is that books published under the Key Approaches banner will be viewed as dynamic and energizing contributions to criminological debates. Globalization & Crime – the second book in the series – is no exception in this regard. In addressing topics ranging from human trafficking and the global sex trade to the protection of identity in cyberspace and post 9/11 anxieties, Katja Franko Aas has cap- tured some of the most controversial and pressing issues of our times. Not only does she provide a comprehensive overview of existing debates about these subjects but she moves these debates forward, offering innovative and challenging ways of thinking about familiar contemporary concerns. I believe that Globalization & Crime is the most important book published in this area to date and it is to the author’s great credit that she explores the complexities of transnational crime and responses to it in a manner that combines sophistication of analysis with eloquence of expression. As one of the leading academics in the field – and someone who is genuinely engaged in dialogue about global ‘crime’ issues at an international level, Katja Franko Aas is ideally placed to write this book, and I have no doubt that it will be read and appreciated by academics around the world. -

Negroes Are Different in Dixie: the Press, Perception, and Negro League Baseball in the Jim Crow South, 1932 by Thomas Aiello Research Essay ______

NEGROES ARE DIFFERENT IN DIXIE: THE PRESS, PERCEPTION, AND NEGRO LEAGUE BASEBALL IN THE JIM CROW SOUTH, 1932 BY THOMAS AIELLO RESEARCH ESSAY ______________________________________________ “Only in a Negro newspaper can a complete coverage of ALL news effecting or involving Negroes be found,” argued a Southern Newspaper Syndicate advertisement. “The good that Negroes do is published in addition to the bad, for only by printing everything fit to read can a correct impression of the Negroes in any community be found.”1 Another argued that, “When it comes to Negro newspapers you can’t measure Birmingham or Atlanta or Memphis Negroes by a New York or Chicago Negro yardstick.” In a brief section titled “Negroes Are Different in Dixie,” the Syndicate’s evaluation of the Southern and Northern black newspaper readers was telling: Northern Negroes may ordain it indecent to read a Negro newspaper more than once a week—but the Southern Negro is more consolidated. Necessity has occasioned this condition. Most Southern white newspapers exclude Negro items except where they are infamous or of a marked ridiculous trend… While his northern brother is busily engaged in ‘getting white’ and ruining racial consciousness, the Southerner has become more closely knit.2 The advertisement was designed to announce and justify the Atlanta World’s reformulation as the Atlanta Daily World, making it the first African-American daily. This fact alone probably explains the advertisement’s “indecent” comment, but its “necessity” argument seems far more legitimate.3 For example, the 1932 Monroe Morning World, a white daily from Monroe, Louisiana, provided coverage of the black community related almost entirely to crime and church meetings. -

Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-9-2017 The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 Allyson Compton CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/166 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Breath Seekers: Race, Riots, and Public Space in Harlem, 1900-1935 by Allyson Compton Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: April 10, 2017 Kellie Carter Jackson Date Signature April 10, 2017 Jonathan Rosenberg Date Signature of Second Reader Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Public Space and the Genesis of Black Harlem ................................................. 7 Defining Public Space ................................................................................................... 7 Defining Race Riot ....................................................................................................... 9 Why Harlem? ............................................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2: Setting -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964

Harlem's Rent Strike and Rat War: Representation, Housing Access and Tenant Resistance in New York, 1958-1964 Mandi Isaacs Jackson Housing Access On December 30,1963, photographers patiently awaited the arrival of ten ants from two Harlem tenements scheduled to appear in Manhattan Civil Court on charges of rent non-payment. Since the chilly early morning hours, photog raphers had mulled around outside the civil courthouse on Centre Street, mov ing cameras from one shoulder to the other, lighting and extinguishing ciga rettes. The press had been tipped off by strike leaders that they would smuggle dead rats into the courtroom to serve as both symbol and evidence of what the media liked to call their "sub-human" living conditions. These defendants rep resented thirteen families on 117th Street who had been withholding rent in protest of the their buildings' combined 129 building violations, pointing to "dark and littered" hallways, "crumbly" ceilings, and broken windows, water, and heat. But what photographers waited to capture in black and white were the "rats as big as cats" that plagued the dilapidated buildings. "They so big they can open up your refrigerator without you!" reported one tenant.1 Finally, at 11:30 am, the tenants waded through the river of television and newspaper cameras and removed three dead rodents from a milk container, a paper bag, and a newspaper. Flash bulbs exploded. As he displayed the enor mous dead rat he had brought from home, tenant William D. Anderson told a New York Amsterdam News reporter, "This is the only way to get action from 0026-3079/2006/4701-053S2.50/0 American Studies, 47:1 (Spring 2006): 53-79 53 54 Mandi Isaacs Jackson the property owners who don't care anything about the tenants."2 The grotesque statement made by the rat-brandishing rent strikers was, as William Anderson told the reporters, an eleventh-hour stab at the visibility tenants were consis tently denied. -

Finding and Using African American Newspapers

Finding and Using African American Newspapers Timothy N. Pinnick [email protected] http://blackcoalminerheritage.net/ INTRODUCTION African American researchers will find black newspapers an extremely valuable part of their search strategy. Although mainstream newspapers should always be consulted, African American newspapers will provide nuggets of information that can be found nowhere else. Although the first African American newspaper was established in 1827, it is in the post Civil War period that the black press experienced tremendous growth. Hundreds of newspapers appeared to quench the thirst for knowledge in the newly freed slaves, and to provide an accurate and positive image of the race. Clint C. Wilson took the incomplete manuscript of the foremost historian of the African American press, Armistead Pride and produced A History of the Black Press in 1997. It is a great source of information on black newspapers. Another worthwhile source can be found online at the public television website of PBS. They produced the documentary film, “The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords” in 1999, and their website is rich in reference material. http://www.pbs.org/blackpress/index.html VALUE OF BLACK NEWSPAPERS Aside from the most obvious benefit of locating obituaries, researchers can discover: an exact or nearly exact event date (birth, death, or marriage) of an ancestor, therefore enhancing the odds of a successful outcome when the eventual request for the vital record is made. Remember, some places will only search a short span of years in their index, and charge you whether they find the record or not. additional information on the event that will not be found on the vital record. -

The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933

© Copyright 2015 Alexander James Morrow i Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: James N. Gregory, Chair Moon-Ho Jung Ileana Rodriguez Silva Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of History ii University of Washington Abstract Laboring for the Day: The Pacific Coast and the Casual Labor Economy, 1919-1933 Alexander James Morrow Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James Gregory Department of History This dissertation explores the economic and cultural (re)definition of labor and laborers. It traces the growing reliance upon contingent work as the foundation for industrial capitalism along the Pacific Coast; the shaping of urban space according to the demands of workers and capital; the formation of a working class subject through the discourse and social practices of both laborers and intellectuals; and workers’ struggles to improve their circumstances in the face of coercive and onerous conditions. Woven together, these strands reveal the consequences of a regional economy built upon contingent and migratory forms of labor. This workforce was hardly new to the American West, but the Pacific Coast’s reliance upon contingent labor reached its apogee after World War I, drawing hundreds of thousands of young men through far flung circuits of migration that stretched across the Pacific and into Latin America, transforming its largest urban centers and working class demography in the process. The presence of this substantial workforce (itinerant, unattached, and racially heterogeneous) was out step with the expectations of the modern American worker (stable, married, and white), and became the warrant for social investigators, employers, the state, and other workers to sharpen the lines of solidarity and exclusion. -

Harlem Y Summer/Fall 2018

DISCOVER 180 West 135th Street YOUR Y New York, NY 10030 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem HARLEM Y facebook.com/harlemy SUMMER/FALL 2018 180 West 135th Street New York, NY 10030 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem GET INVOLVED JOIN US TO HELP NEW YORKERS SUCCEED GIVE YOUR FELLOW NEW YORKERS A CHANCE TO THRIVE Visit www.ymcanyc.org/give to support OUR VISION our nonprofit mission. Active, engaged New Yorkers VOLUNTEER TO STRENGTHEN YOUR COMMUNITY building stronger communities. Email [email protected] to learn more. WATCH US GROW IN THE BRONX OUR MISSION Visit www.ymcanyc.org/bronx2020 to monitor progress on our new We’re here for all New Yorkers — Bronx branches. to empower youth, improve health, FOLLOW US and strengthen community. Check Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for the latest updates on everything happening at New York City’s YMCA. HARLEM INFORMATION STAFF LISTING HOURS OF OPERATION 2018 SUMMER/FALL SESSION & REGISTRATION DATES Steve Lawrence – Executive Director ADULTS 212-912-2111, [email protected] Monday - Friday: 5:30 AM - 11:00 PM SUMMER REGISTRATION DATES Saturday 6:00 AM - 8:00 PM Member: June 16, 2017 Latoya Jackson - Associate Executive Director Sunday: 8:00 AM - 8:00 PM Community: June 23, 2017 212-912-2162, [email protected] Jamal Williams - Fund Development & TEENS SESSION DATES: Communications Director (School holidays & summer hours vary; refer to July 2, 2018 - August 26, 2018 212-912-2164, [email protected] website for a current schedule.) Monday - Friday: 2:30 - 8:00 PM FALL I REGISTRATION DATES Saturday -

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activ

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activities, and Websites A to G Environmental and Ocean Literacy Environmental literacy is key to preserving the nation's natural resources for current and future use and enjoyment. An environmentally literate public results in increased stewardship of the natural environment. Many organizations are working to increase the understanding of students, teachers, and the general public about the environment in general, and the oceans and coasts in particular. The following are just some of the large-scale and regional initiatives which seek to provide standards and guidance for our educational efforts and form partnerships to reach broader audiences. (In the interest of brevity, please forgive the abbreviations, the abbreviated lists of collaborators, and the lack of mention of funding institutions). The lists are far from inclusive. Please send additional entries for inclusion in future newsletters. Background Documents Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy NAAEE has released Developing a Framework for Assessing Environmental Literacy, developed by researchers, educators, and assessment specialists in social studies, science, environmental education, and others. A presentation about the framework and accompanying documents are available on this website. http://www.naaee.net/framework Executive Order for the Stewardship of Our Oceans, Coasts, and Great Lakes President Barak Obama signed an Executive Order establishing the National Ocean Council. The Executive Order established for the first time a comprehensive, integrated national policy for the stewardship of the ocean, our coasts, and Great Lakes, which sets our nation on a path toward comprehensive planning for the preservation and sustainable uses of these bodies of water. -

To View Proposal

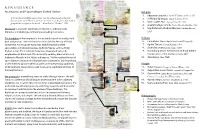

R E N A I S S A N C E Architecture and Placemaking in Central Harlem Religion 1. Abyssinian Baptist: Charles W. Bolton & Son, 1923 It is true the formidable centers of our race life, educational, industrial, 2. St Philip's Episcopal: Tandy & Foster, 1911 financial, are not in Harlem, yet here, nevertheless are the forces that make a 3. Mother AME Zion: George Foster Jr, 1925 group known and felt in the world. —Alain Locke, “Harlem” 1925 4. Greater Refuge Temple: Costas Machlouzarides, 1968 We intend to study the landmarks in Harlem to understand the 5. Majid Malcolm Shabazz Mosque: Sabbath Brown, triumphs and challenges of Black placemaking in America. 1965 The backdrop to this proposal is the national story of inequality, both Culture past and present. Harlem’s transformation into the Mecca of Black 6. Paris Blues: Owned by the late Samuel Hargress Jr. culture that we recognize today was enabled by failed white 7. Apollo Theater: George Keister, 1914 speculation and shrewd business by Black figures such as Philip 8. Studio Museum: David Adjaye, 2021 Payton Junior. The Harlem Renaissance blossomed out of the 9. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: neighborhood’s Black and African identity, enabling Black artists and Charles McKim, 1905; Marble Fairbanks, 2017 thinkers to flourish in the 1920s and beyond. Yet, the cyclical forces of 10. Showman’s Jazz Club speculation, rezoning and rising land values undermine this flourishing and threaten to uproot Harlem’s poorer and mostly Black population, People while landmark designations seek to preserve significant portions of 11. -

Harlem YMCA Winter | Spring 2013

LEARN GROW THRIVE harleM YMCA Winter | SPring 2013 HARLEM YMCA 180 West 135th Street New York, NY 10030 P 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem WHY WE’re Here FOR Nurturing the potential of every child and teen YOUTH We believe that all kids deserve the opportunity to discover who they are and what DEVELOPMENT they can achieve. That’s why, through the YMCA, millions of youth today are cultivating the values, skills and relationships that lead to positive behaviors, better health and educational achievement. FOR Improving our community’s health and well-being HEALTHY In neighborhoods across the five boroughs, the YMCA is a leading voice on health LIVING and well-being. The Y brings families closer together, encourages good health and fosters connections through fitness, sports, fun and shared interests. As a result, nearly 400,000 youth, adults and families are receiving the support, guidance and resources needed to achieve greater health and well-being for their spirit, mind and body. FOR Giving back and providing support to our neighbors SOCIAL The YMCA has been listening and responding to New York City’s most critical social RESPONSIBILITY needs for 160 years. Whether developing skills or emotional well-being through education and training, welcoming and connecting diverse demographic populations through global services, or preventing chronic disease and building healthier communities through collaborations with policymakers, the Y fosters the care and respect all people need and deserve. We’re Here for Good. It’s been the signature phrase of New York City’s YMCA since early 2008, and it describes the Y’s commitment to building the foundations of—and strengthening—our communities, through nurturing the potential of every child and teen, improving community health and well-being and providing opportunities to give back and support neighbors.