Singaporean Film Industry in Transition:Looking for a Creative Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning Through Collaboration and Co-Production in the Singapore Film Industry : Opportunities for Development

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Wong, Caroline & Matthews, Judith (2009) Learning through collaboration and co-production in the Singapore film in- dustry: opportunities for development. In Rose, E & Fisher, G (Eds.) ANZIBA: The Future of Asia-Pacific Business- Beyond the Crisis. ANZIBA, CD Rom, pp. 1-25. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/27761/ c Copyright 2009 please contact the authors This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.anziba.org/ conf.html QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Wong, Caroline and Matthews, Judy H. -

APPENDIX B Information on the Singapore Booth at the Marché Du

APPENDIX B Information on the Singapore Booth at the Marché du Film, Cannes The Singapore film community is represented at the Marché du Film in Cannes, where the Singapore booth is located within the Film ASEAN Pavilion on the riviera (number 117, Village International). Village International at the Marché du Film is the annual forum for world cinema. Information on part of the Singapore delegation/companies at 69th Cannes Film Festival Company Contact Akanga Film Asia Fran Borgia Akanga is the film company behind the two Singapore films [email protected] (Apprentice, A Yellow Bird), selected for the Cannes Film www.akangafilm.com Festival 2016. Akanga Film Asia is an independent production company created in 2005 in Singapore to produce quality films by the new generation of Asian filmmakers. Our projects aim to create a cultural link between Asia and the rest of the world. Titles produced by Akanga include Ho Tzu Nyen’s Here (Cannes Directors’ Fortnight 2009), Boo Junfeng’s Sandcastle (Cannes Critics’ Week 2010), Vladimir Todorovic’s Disappearing Landscape (Rotterdam 2013), Christine Molloy & Joe Lawlor’s Mister John (Edinburgh 2013), Lav Diaz’s A Lullaby To The Sorrowful Mystery (Berlin Competition 2016 – Silver Bear Alfred Bauer Prize), Boo Junfeng’s Apprentice (Cannes Un Certain Regard 2016) and K. Rajagopal’s A Yellow Bird (Cannes Critics’ Week 2016). Clover Films Lim Teck Clover Films Pte Ltd was established in 2009 and [email protected] specialises in the distribution and production of Asian http://www.cloverfilms.com.sg/ movies, with an emphasis on the Singapore and Malaysia markets. -

Intra and Intersentential Code-Switching Phenomena in Modern Malay Songs

3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 24(3): 184 – 205 http://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2018-2403-14 Intra and Intersentential Code-switching Phenomena in Modern Malay Songs WAN NUR SYAZA SAHIRA WAN RUSLI Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia AZIANURA HANI SHAARI Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia SITI ZAIDAH ZAINUDDIN Department of English Language, Faculty of Languages and Linguistics University Malaya [email protected] NG LAY SHI Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia AIZAN SOFIA AMIN Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia ABSTRACT Code-switching has been used in many languages by many different groups of people or speech communities, but little is known about how and why they are used as communicative strategies in modern song lyrics. This paper aims to explore and describe the recent phenomenon of English code-switching in modern Malay songs. 25 modern Malay songs were selected and analysed using Content Analysis. The analysis was made based on Poplack’ Theory as well as the functions of code-switching proposed by Appel and Musyken. Two types of code- switching commonly used in modern Malay songs were discovered. They were intrasentential and intersentential code-switching. The classification of the functions of code-switching was then made based on the six functions of code-switching, which are referential, directive, expressive, phatic, metalinguistic, and poetic. The findings of this research also indicate other functions of code-switching that demonstrate bilingual creativity among songwriters in Malaysia. In conclusion, the findings of this study indicated that code switching in Modern Malay songs is not just a random switch from one code to another but carries certain social functions that emphasize on the establishment of people’s intimacy, solidarity and local identity. -

Singaporean Cinema in the 21St Century: Screening Nostalgia

SINGAPOREAN CINEMA IN THE 21ST CENTURY: SCREENING NOSTALGIA LEE WEI YING (B.A.(Hons.), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF CHINESE STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2013 Declaration i Acknowledgement First and utmost, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Nicolai Volland for his guidance, patience and support throughout my period of study. My heartfelt appreciation goes also to Associate Professor Yung Sai Shing who not only inspired and led me to learn more about myself and my own country with his most enlightening advice and guidance but also shared his invaluable resources with me so readily. Thanks also to Dr. Xu Lanjun, Associate Professor Ong Chang Woei, Associate Professor Wong Sin Kiong and many other teachers from the NUS Chinese Studies Department for all the encouragement and suggestions given in relation to the writing of this thesis. To Professor Paul Pickowicz, Professor Wendy Larson, Professor Meaghan Morris and Professor Wang Ban for offering their professional opinions during my course of research. And, of course, Su Zhangkai who shared with me generously his impressive collection of films and magazines. Not forgetting Ms Quek Geok Hong, Mdm Fong Yoke Chan and Mdm Kwong Ai Wah for always being there to lend me a helping hand. I am also much indebted to National University of Singapore, for providing me with a wonderful environment to learn and grow and also awarding me the research scholarship and conference funding during the two years of study. In NUS, I also got to know many great friends whom I like to express my sincere thanks to for making this endeavor of mine less treacherous with their kind help, moral support, care and company. -

Download Film I Not Stupid Too 2

Download film i not stupid too 2 click here to download Nonton I Not Stupid Too Subtitle Indonesia, Download Gratis Film Drama Subtitle download film i not stupid too ∞ download i not stupid too 2 subtitle. CD 1 www.doorway.ru?v=JsdKL9lK4eM. Nonton Film I Not Stupid Too () Subtitle Indonesia. Nonton Movie dengan pas dan bagus. Watch movies streaming download film online. I Not Stupid Too (). A comedy about the difficult relationships parents have with their children today. Set in Singapore's fast-paced society, eight year old. Sebuah Film Singapura dan sekuel film , saya tidak bodoh. Sebuah komedi satir, I Not Stupid Too menggambarkan kehidupan, perjuangan dan. Download Subtitle Indonesia I Not Stupid Too. Sebuah Film Singapura dan sekuel film , saya tidak bodoh. Sebuah komedi satir, I Not Stupid Too. I am Not Stupid too + Sub Indonesia () p WebDL Link download Via Google Drive. Movie 1: Movie 2: www.doorway.ru sub 1. File Film. I Not Stupid Too – CD 1. I Not Stupid Too – CD 2. Subtitle Indonesia. I Not Stupid Too – CD 1. I Not Stupid Too – CD2. semoga. Nonton I Not Stupid () Film Subtitle Indonesia Streaming Movie Download. Nonton I Not Terry, a spoilt brat is just too lazy a student. Download Film I'm Not Stupid Too. Posted by cinemax Posted on with No comments. I'm Not Stupid Too. Data Rilis: 26 january Quality: CDRIP. Watch online and download I Not Stupid Too drama in high quality. Various formats from p to p I Not Stupid Too. Other name: Children are not stupid 2. -

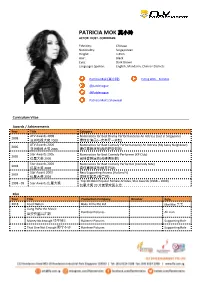

Patricia Mok 莫小玲 Actor

PATRICIA MOK 莫小玲 ACTOR. HOST. COMEDIAN. Ethnicity: Chinese Nationality: Singaporean Height: 1.65m Hair: Black Eyes: Dark Brown Languages Spoken: English, Mandarin, Chinese Dialects Patricia Mok (莫小玲) FLYing With... Pat Mok @patdevogue @Patdevogue Patricia Mok’s Showreel Curriculum Vitae Awards / Achievements Year Title Category ATV Awards 2008 Nomination for Best Drama Performance by An Actress (Just in Singapore) 2008 亚洲电视大奖 2008 最佳女演员(一房半厅一水缸) ATV Awards 2006 Nomination for Best Comedy Performance by An Actress (My Sassy Neighbour) 2006 亚洲电视大奖 2006 最佳喜剧演员(我的野蛮邻居) Star Awards 2005 Nomination for Best Comedy Performer (KP Club) 2005 红星大奖 2005 最佳喜剧演员(鸡婆俱乐部) Star Awards 2004 Nomination for Best Comedy Performer (Comedy Nite) 2004 红星大奖 2004 最佳喜剧演员(搞笑行动) Star Award 2003 Best Supporting Actress (Holland V) 2003 红星大奖 2003 最佳女配角 (荷兰村) Top 20 Most Popular Female Artistes, Star Awards (1998 – 2009) 1998 - 09 Star Awards 红星大奖 红星大奖 20 大最受欢迎女艺 Film Year Title Production Company Director Role 2018 Food Nation Boku Films Pte Ltd Mei Mei 美美 Liang PoPo the Movie Raintree Pictures Ah Lian 梁婆婆重出江湖 Money No Enough 钱不够用 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role That One Not Enough 那个不够 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role I Not Stupid 小孩不苯 Raintree Pictures Discipline Master HomeRun 跑吧孩子! Raintree Pictures Supporting Role We Are Family 2006 Hong Kong Supporting Role 左麟右李之我爱医家人 I Not Stupid Too 小孩不苯 2 Raintree Pictures Discipline Master Lead Role Happy Go Lucky 福星到 Chua Movie Pte Ltd (Donna) Dance Dance Dragon 籠眾舞 Raintree Pictures Supporting Role As pregnant Taxi Taxi -

Cinema and Television in Singapore Social Sciences in Asia

Cinema and Television in Singapore Social Sciences in Asia Edited by Vineeta Sinha Syed Farid Alatas Chan Kwok-bun VOLUME 16 Cinema and Television in Singapore Resistance in One Dimension By Kenneth Paul Tan LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 Front cover photograph © Kenneth Paul Tan This book is printed on acid-free paper. A C.I.P. record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISSN 1567-2794 ISBN 978 90 04 16643 1 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands table of contents v TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations . vii Acknowledgments . ix Introduction . xi Chapter One One-Dimensional Singapore . 1 Chapter Two The Culture Industry in Renaissance-City Singapore . 37 Chapter Three Singapore Idol: Consuming Nation and Democracy . 77 Chapter Four Under One Ideological Roof: TV Sitcoms and Drama Series . 107 Chapter Five Imagining the Chinese Community through the Films of Jack Neo . 145 Chapter Six The Tragedy of the Heartlands in the Films of Eric Khoo . -

Tv Highlights for Central

MediaCorp Pte Ltd Daily Programme Listing okto WEDNESDAY 1 AUGUST 2012 9.00AM Pororo The Little Penguin (Sr 3 / Eps 25 - 28 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 9.30 Dive Olly Dive (Sr 2 / Eps 31 - 32 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 10.00 oktOriginal: Zoom, Zim, Zam (Ep 13 / Local / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) "Zoom Zim Zam” is a, phonics based educational pre-school series. The series features Zoomba, Zimba and Zamba literacy superheroes. Who together with their friends learn about the world around them and the sounds that alphabets make. The series will feature original songs and Dance as part of the programme. Theme for today is about Different Mood Looks and the sounds of the letter M. 10.30 Bo On The Go (Sr 1 / Ep 1 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 11.00 Milly, Molly (Sr 2 / Eps 19 - 20 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 11.30 Bob The Builder (Sr 17 & 18 / Eps 29 - 30 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 12.00NN ABC Monsters (Ep 14 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 12.30PM Noddy In Toyland (Eps 3 - 4 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 1.00 oktOriginal: Zoom, Zim, Zam (Ep 13 / Local / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 1.30 Bo On The Go (Sr 1 / Ep 1 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 2.00 Milly, Molly (Sr 2 / Eps 19 - 20 / Preschool) (幼儿乐园) 2.30 Bob The Builder (Sr 17 & 18 / Eps 29 - 30 / Preschool / R) (幼儿乐园) 3.00 oktOriginal: The Big Q (Sr 3 / Ep 11 / Local Info-ed / R) (益智节目) 3.30 oktOriginal: Kids United (Sr 1 / Ep 4 / Local Drama / Schoolkids / R) (电视剧) 4.00 oktOriginal: Champs Challenge: Wise Up To Money (Ep 5 / Local Info-ed / Schoolkids / R) (益智节目) 4.30 oktOriginal: Bring Your Toothbrush (Sr 2 / Ep 13 / Local Info-ed / Schoolkids / R) (益智节目) 5.00 Watership Down (Ep 23 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) 5.30 The Adventures Of Paddington Bear (Ep 23 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) okto WEDNESDAY 1 AUGUST 2012 6.00PM Edebits (Eps 17 - 18 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) There is a big storm outside and Lou and Morgan are rescued by Nil and Mandi who take them to their base. -

Proceedings of China's First International Symposium on Ethnic

Proceedings of China’s First International Symposium on Ethnic Languages and Culture under “The Belt and Road Initiatives” July 18-21, 2016, Beijing, China The American Scholars Press Editors: Jia Hongwei, Lisa Hale, and Jin Zhang Cover Designer: Wang Jun Published by The American Scholars Press, Inc. The Proceedings of China’s First International Symposium on Ethnic Languages and Culture under “The Belt and Road Initiatives” is published by the American Scholars Press, Inc., Marietta, Georgia, USA. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 2016 by the American Scholars Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9721479-3-4 Printed in the United States of America 2 Foreword I am very privileged to be invited to attend the China’s 1st International Symposium on Ethnic Languages and Culture under “The Belt and Road Initiatives” held in mid-July 2016 at the Fragrance Hill Hotel in the western suburban area of Beijing, China. The beautiful hotel is surrounded by flourishing trees, various kinds of flowers, and a grander academic extravaganza with internationally known experts’ visits. This symposium attracted more than 150 scholars from all parts of China, and some scholars from abroad. The discussions on Chinese (ethnic) and foreign languages and culture, literature, language teaching, translation, and academic methods were the magnet for their coming together. As an academic platform established by the Beijing Teachers Training Center for Higher Education, and based in Beijing, the capital of China, it serves as an important means to create close ties and a network among scholars in China and abroad. -

CITED FILMS by JACK NEO, ERIC KHOO, and ROYSTON TAN Jack

appendix b 271 APPENDIX B: CITED FILMS BY JACK NEO, ERIC KHOO, AND ROYSTON TAN Jack Neo Homerun. 2003. Jack Neo (director, writer, and actor), Daniel Yun (executive produc- er), Titus Ho (producer), and Chan Pui Yin (producer). DVD, distributed by Vid- eoVan Entertainment Industries Pte Ltd. I Do, I Do. 2005. Jack Neo (director, executive producer, producer, writer, and actor), Lim Boon Hwee (director), Daniel Yun (executive producer), Asun Mawardi (ex- ecutive producer and producer), Jareuk Kaljareuk (executive producer), Titus Ho (producer), Chan Pui Yin (producer), Seah Saw Yam (producer), and Boris Boo (writer). DVD, distributed by Scorpio East Entertainment Pte Ltd. I Not Stupid. 2002. Jack Neo (director, writer, and actor), Daniel Yun (executive pro- ducer), Chan Pui Yin (producer), and David Leong (producer). DVD, distributed by VideoVan Entertainment Industries Pte Ltd. I Not Stupid Too. 2006. Jack Neo (director, writer, and actor), Daniel Yun (Executive producer), Chan Pui Yin (producer), Seah Saw Yam (producer), and Rebecca Leow (writer). DVD, distributed by Scorpio East Entertainment Pte Ltd. Just Follow Law. 2007. Jack Neo (director, producer, and writer), Irene Kng (Executive producer), Teck Lim (executive producer), Sok Mien Koo (producer), Simon Le- ong (producer), Hazel Wong (producer), Sek Yieng Bon (writer), Boris Boo (writ- er), Wei Lyn Tan (writer), and Michael Woo (writer). DVD, distributed by InnoForm Media Pte Ltd. Liang Po Po: The Movie. 1999. Jack Neo (writer and actor), Bee Lian Teng (director), Eric Khoo (executive producer), Daniel Yun (executive producer), and David Le- ong (producer). VCD, distributed by VideoVan Entertainment Industries Pte Ltd. Money No Enough. -

The Usage of Multiple Languages and Dialects in Films

THE USAGE OF MULTIPLE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN FILMS Tan Su Peng Bachelor of Applied Arts with Honours (Cinematography) 2013 THE USAGE OF MULTIPLE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN FILMS TAN SU PENG This project is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Applied Arts with Honours (Cinematography) Faculty of Applied and Creative Arts UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAWAK 2013 UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SARAWAK Please tick Final Year Project Report (√) Masters PhD DECLARATION OF ORIGINAL WORK This declaration is made on the ……………..day of……………..2013. Student’s Declaration: I, TAN SU PENG (Matric No. 28474), Faculty of Applied and Creative Arts), hereby declare that the work entitled THE USAGE OF MULTIPLE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN FILMS is my original work. I have not copied from any other students’ work or from any other sources except where due reference or acknowledgement is made explicitly in the text, nor has any part been written for me by another person. ____________________ ________________________ Date submitted Tan Su Peng (28474) Supervisor’s Declaration: I, YOW CHONG LEE, hereby certifies that the work entitled THE USAGE OF MULTIPLE LANGUAGES AND DIALECT IN FILMS was prepared by the above named student, and was submitted to the “FACULTY OF APPLIED AND CREATIVE ARTS” as a partial fulfillment for the conferment of BACHELOR OF APPLIED ARTS WITH HONOURS, and the aforementioned work, to the best of my knowledge, is the said student’s work. Received for examination by: _____________________ Date: ____________________ -

The Revival of Singaporean Cinema 1995–2014

BIBLIOASIA APR–JUN 2015 Vol. 11 / Issue 01 / Feature The Rise of Auteur Cinema industry. The feat is all the more amazing when one considers the fact that Mee Pok The first glimmer of hope for the revival Man was able to blaze a trail of its own, Is 2015 going to be a watershed year for of local cinema appeared that same year with none of the baggage connected with Singaporean cinema? Two highly symbolic when Eric Khoo’s August bagged the award the golden age of Singaporean cinema as events have paved the way for it, and, when for Best Singapore Short Film at the newly embodied by the Shaw and Cathay studios taken together, encapsulate the larger picture inaugurated awards. Encouraged by the of yesteryear. Endowed with all the traits of Singaporean film history, from its origins award, Khoo successively directed a few of an indie production, the film is clearly at the turn of the 20th century until today. more short films: Carcass (1992), which the work of an auteur. i Firstly, Run Run Shaw, co-founder in draws parallels between the life of a busi- Mee Pok Man was the first Singa- 1926 of the oldest Singaporean film empire, nessman and that of a butcher, and was the porean feature film to be entered for the passed away in March 2014. His death – at first local film to be given an R(A) rating; SIFF’s Silver Screen Awards, and it was age 106 – brought to full closure the first and Pain (1994), which recounts the story subsequently invited to over 30 interna- great cycle of Singaporean film history of a sado-masochistic young man, and tional film festivals, including the Berlin (largely predating the country’s Independ- won Khoo the Best Director and Special and Venice festivals.