PENNZOIL V. TEXACO 77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halronmicreditapplication.Pdf

CONTINUING GUARANTY FOR VALUE RECEIVED, and to induce HALRON LUBRICANTS INC. of Green Bay, Wisconsin (“Halron”) to extend credit to (“Debtor”), the Insert Company Name Here undersigned (“Guarantor”, whether one or more) jointly and severally guarantee payment to Halron when due or, to the extent not prohibited by law, at the time Debtor becomes the subject of bankruptcy or other insolvency proceedings, all debts, obligations and liabilities of every kind and description, arising out of the credit granted by Halron to Debtor (the “Obligations”), and to the extent not prohibited by law, all costs, expenses and fees at any time paid or incurred in endeavoring to collect all or part of the Obligations or to realize upon this Guaranty. This includes, but is not limited to any collection fee, legal proceeding and/or reasonable attorney’s fees. No claim which Guarantor may have against a co-guarantor of any of the Obligations or against Debtor shall be enforced nor any payment accepted until the Obligations are finally paid in full. To the extent not prohibited by law, this Guaranty is valid and enforceable against Guarantor even though any Obligation is invalid and unenforceable against Debtor. To the extent not prohibited by law, Guarantor expressly waives notice of the acceptance, the creation of any present or future Obligation, default under any Obligation, proceedings to collect from Debtor or anyone else, and all diligence of collection and presentment, demand, notice and protest. This is a continuing Guaranty and shall remain in full force and effect until Halron receives written notice of its revocation signed by Guarantor or actual notice of the death of Guarantor. -

Rouseville Refinery Plant 1

Environmental Covenant When recorded, return to: GOC Property Holdings, LLC, 175 Main Street, Oil City, PA 16301 GRANTOR: GOC Property Holdings, LLC PROPERTY ADDRESS: 55 Main Street, Rouseville, PA 16344 ENVIRONMENTAL COVENANT This Environmental Covenant is executed pursuant to the Pennsylvania Uniform Environmental Covenants Act, Act No. 68 of2007, 27 Pa. C.S. §§ 6501-6517 (UECA). This Environmental Covenant subjects the Property identified in Paragraph 1 to the activity and/or use limitations in this document. As indicated later in this document, this Environmental Covenant has been approved by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (Department). 1. Property affected. The property affected (Property) by this Environmental Covenant is located in the Borough ofRouseville, Venango County. The postal street address of the Property is: 55 Main Street, Rouseville, PA. The County Parcel Identification No. of the Property is: 25-03-01 C and 25-03-01D. The latitude and longitude of the center of the Property affected by this Environmental Covenant is: 41 degrees - 28 minutes - 0.69 seconds (north) and 79 degrees - 41 minutes - 31.45 seconds (west). The property has been known by the following name: Rouseville Refinery Plant 1. The Primary Facility (PF) No. of the Rouseville Refinery Plant 1 is: 612975. The Tank Facility ID No. ofthe Rouseville Refinery Plant 1 is: 61-91604. A complete description of the Property is attached to this Environmental Covenant as Exhibit. A. A map of the Property is attached to this Environmental Covenant as Exhibit B. 2. Property Owner I GRANTOR. GOC Property Holdings, LLC, ("GOC") is the Owner of the Property and "GRANTOR" of this Environmental Covenant. -

Pennzoil-Quaker State Co. V. Miller Oil & Gas Operations

Case: 13-20558 Document: 00512945125 Page: 1 Date Filed: 02/23/2015 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT United States Court of Appeals Fifth Circuit No. 13-20558 FILED February 23, 2015 Lyle W. Cayce PENNZOIL-QUAKER STATE COMPANY Clerk Plaintiff - Appellant v. MILLER OIL AND GAS OPERATIONS; WILLIAM J. MILLER; MILLER OIL & GAS OPERATIONS, LIMITED; METRON MANAGEMENT COMPANY, L.L.C.; WILLIAM CYLVESTOR WILLIAMS, JR.; BILL LINCOLN, Defendants - Appellees Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas Before JOLLY, HIGGINBOTHAM, and OWEN, Circuit Judges. PATRICK E. HIGGINBOTHAM, Circuit Judge: The holder of a trademark has certain rights, among them the power to prohibit another entity from using its mark without its consent. Those rights are subject to equitable defenses, including acquiescence, where the markholder affirmatively represents to another that it may use its mark, who then relies on that representation to its prejudice. This case requires us to clarify the role that undue prejudice plays in the analysis of acquiescence. Concluding that the defendant here failed to demonstrate that it was unduly prejudiced by any representations made by the markholder, we reverse. Case: 13-20558 Document: 00512945125 Page: 2 Date Filed: 02/23/2015 No. 13-20558 I. This is a dispute about a commercial relationship, one largely defined by the use of another’s intellectual property, gone bad. Pennzoil-Quaker State Company (“Pennzoil”), makes and sells automotive lubricants, including motor oil. As part of its business, Pennzoil owns several federally recognized trademarks and trade dress,1 notably the name “Pennzoil,” the “Pennzoil Across the Bell” logo, and a color scheme involving the use of yellow with black accents. -

Win at Daytona Page 3

ALUMNIPUBLISHED FOR SHELL ALUMNI IN THE AMERICAS | WWW.SHELL.US/ALUMNINEWSJUNE 2015 UNLOCKING SHELL MAKES HISTORY SHELL IN THE ARCTIC ENERGY ON NEW YORK STOCK IN ULTRA- EXCHANGE Answers to commonly DEEPWATER asked questions. Shell Midstream Partners 3D printing saves goes public. months of work. WIN AT DAYTONA PAGE 3 20154305 ComPgs.indd 1 5/13/15 5:20 AM 2 SHELL NEWS ALUMNINEWS AlumniNews is published for Shell US and Canada. Editors: Design: Natalie Mazey and Jackie Panera Production Centre of Excellence Shell Communications The Hague Writer/copy editor: Shell Human Resources: Susan Diemont-Conwell Annette Chavez Torma Communications and Alicia Gomez A WORD FROM OUR EDITORS We know that many of you as former Shell GO GREEN employees field questions from time to time Sign up to receive the newsletter electronically by on Shell projects and the direction of the visiting www.shell.us/alumni. While you’re there, read industry. While our goal is to provide you the latest news and information about Shell. Thank you to those who have already chosen to go green! with news about the business, some alumni expressed a need for messaging documents that would help explain Shell’s stance on CONTENTS particular hot-button issues. This issue, we’ve sought to answer commonly asked questions about our role in the Arctic. We hope this information will prove helpful when HIGHLIGHTS discussing the project with friends and family. Shell technology under the hood 03 Joey Logano wins his first-ever Daytona 500. Also in this issue, we’ve shared a major success at the Daytona 500—a big win for Unlocking energy in ultra-deepwater driver Joey Logano and for Shell as 04 3D printing saves months of work. -

D:\Documents and Settings\Ghales\My Documents

ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED CONSENT ORDER TO AID PUBLIC COMMENT In the Matter of Shell Oil Company and Pennzoil-Quaker State Company File No. 021 0123, Docket No. C-4059 I. Introduction The Federal Trade Commission (“Commission” or “FTC”) has issued a complaint (“Complaint”) alleging that the proposed merger of Shell Oil Company (“Shell”) and Pennzoil- Quaker State Company (“Pennzoil”) (collectively “Respondents”) would violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, as amended, 15 U.S.C. § 45, and has entered into an agreement containing consent orders (“Agreement Containing Consent Orders”) pursuant to which Respondents agree to be bound by a proposed consent order that requires divestiture of certain assets (“Proposed Consent Order”) and a hold separate order that requires Respondents to hold separate and maintain certain assets pending divestiture (“Hold Separate Order”). The Proposed Consent Order remedies the likely anticompetitive effects arising from Respondents’ proposed merger, as alleged in the Complaint, and the Hold Separate Order preserves competition pending divestiture. II. Description of the Parties and the Transaction Shell Oil Company, headquartered in Houston, Texas, is the United States operating entity for the Royal Dutch/Shell Group of Companies (collectively referred to as “Shell”). Shell is engaged in virtually all aspects of the energy business, including exploration, production, refining, transportation, distribution, and marketing. As part of the relief ordered by the Commission in Chevron/Texaco, Docket C-4023 (Jan. 2, 2002), Texaco divested its interest in Equilon Enterprises LLC to Shell and its interest in Motiva Enterprises LLC to Shell and Saudi Refining Company. -

Fuentes V. Royal Dutch Shell PLC Et

Case 2:18-cv-05174-AB Document 1 Filed 11/29/18 Page 1 of 32 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA VICTOR FUENTES, individually Civil Action No.: ( %- S- J7 'f and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Complaint -- Class Action Plaintiff, Jury Trial Demanded v. / ROY AL DUTCH SHELL PLC, SHELL OIL COMPANY, PENNZOIL-QUAKER STATE COMP ANY and JIFFY LUBE INTERNATIONAL, INC., Defendants. INTRODUCTION I. Average hourly pay at Jiffy Lube shops in the United States ranges from approximately $8.14 per hour for an Entry Level Technician to $16. 88 per hour for an lnspector. 1 In contrast, the United States' "living wage"-the ··approximate income needed to meet a family's basic needs"-is $15.12. ~ 2. Likely contributing to this wage gap, according to a study by two Princeton economists, are no-poach provisions in franchise agreements which 1 https://www .indeed.com/cmp/Jiffy-Lube/salaries 2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), http://bit.ly/20P0QvY. -1- Case 2:18-cv-05174-AB Document 1 Filed 11/29/18 Page 2 of 32 prohibit one shop owner from offering work to employees of another shop owner. 3 Jiffy Lube-which has more than 2,000 shops across the country imposed such a no-poach clause in both of its standard franchise agreements. 4 Owners of a Jiffy Lube franchise, for example, cannot hire anyone who works or has worked at another Jiffy Lube within the previous six months. One of the Princeton study' s authors explains that these no-poach provisions can "significantly influence pay" by obviating the need for franchise owners to compete for the best workers. -

October 1990 HOUSTON GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY BULLETIN Vol

October, 1990 BULLETIN 1 HOUSTON GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY t 7 dume 33 rmber 2 CHECK OUT THE CARBONATE FIELD TRIP! Seepage12 GCAGS CONVENTION See pages 8 & 40 HGS SHRIMP PEEL See page 32 IN THIS ISSUEoo. - Deep Oil Prospects in Trinidad .................................. Page 16 - RCRA: A Historical Perspective ................................. Page 22 - Re-evaluating the Potential of Old Plays ........................ Page 25 - Energy and Destiny: We Must Control Both ..................... Page 29 - Chainsaws and Computers ..................................... Page 42 PL US MORE! (For October Events, see page 1 and Geoevents section, page 33) E rom mne-wem to Atlas Wireline Services I Founded in 1932 as Lane-Wells Co., Atlas 0 Wlreline conveyance servioes - br extended- Wiline Services is now a division of Western reach, horizontal, and difficult-to-service Atlas International, offuing comprehensive wells wireline services worldwide. We've continually tl Global services - a single service from one enhanced our capabilities to offer the latest in location in 1932 to over 100 services from digital data acquisition, analysis, and compietion 80 worldwide locations services for every stage in the life of a well: -. -. Openhole senices - pipe recovery to CBILm 7 ATLAB (Circumferential Borehole Imaging Log) WIREUNE Westam Atlam 0 Cased hde services - perforating to pulsed b'iteirnational P.O. Box 1407 neutron logging Houston. Texas 77251-1407 Produdion 0 bgg@ scnices-injection Open Hole Sewices (713) 972-5739 operations to geothermal services Cased Hole Services (7 13) 972-5766 7he Atlas Advmtage HGS OCTOBER EVENTS MEETINGS OCTOBER 8,1990 (Dinner Meeting) "Evaluation of Untested Stratigraphic Traps in a Pleistocene Canyon-Fill Complex, Offshore Louisiana" Jim Geitgey (see page 10) Westin Oaks Hotel, 5011 Westheimer Social Period 5:30 p.m., Dinner and Meeting 6:30 p.m. -

September 2016 Newsline

September 2016 IT’S GAME DAY! Time to Kick Off United Way Campaign Members of the NMC United Way Committee are pictured with celebrity judges at the site’s annual campaign kickoff. The Pot Lickers Kast Iron Krooks Cast Iron Kings n south Louisiana there is only one way to enjoy Game The all-time leading Saints rusher, who Day and that’s with a spicy dish of jambalaya and a serves as WWL 870 AM Radio’s Saints Iside of gumbo. Norco Manufacturing Complex employees color analyst, joined WWL 870 AM kicked off the site’s annual United Way of St. Charles Radio sports reporters Kristian Garic campaign with a Game Day theme including a cooking and T-Bob Hebert, and St. Charles competition and fund-raising rally. A special appearance Parish Chief Administrative Officer by New Orleans Saints Hall of Famer Deuce “#26” Billy Raymond as judges for a jambalaya McAllister was the highlight of the football-themed event. and gumbo cookoff. Eighteen employee The Gumbeaux Du-eaux teams prepared jambalaya or gumbo McAllister discussed the importance of giving back to entries in the Battle for the Paddle. The the community as he spoke with employees, emphasizing first and second place teams in each the need to give back every day, not just during times category will represent NMC at the of extraordinary need such as recent flooding in south United Way of St. Charles Battle for the Louisiana. Paddle on October 6th. Continued on Page 2 Continued From Page 1 “NORCO MANUFACTURING COMPLEX has a reputation for UNITED WAY, sponsoring the best cookoff and best kickoff to a United Way campaign,” Every Day said General Manager Brett Woltjen, urging employees to continue that How do you define a disaster? reputation by meeting the site goal of In Louisiana, the answers raising one million dollars. -

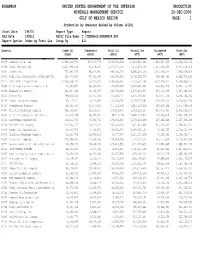

Ranking Operator by Gas 1947

PDRANKOP UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PRODUCTION MINERALS MANAGEMENT SERVICE 22-DEC-2000 GULF OF MEXICO REGION PAGE: 1 Production by Operator Ranked by Volume (4120) Start Date : 194701 Report Type : Report End Date : 199512 ASCII File Name: C:\TIMSWork\PDRANKOP.DAT Report Option: Order by Total Gas Group By : All Operator Crude Oil Condensate Total Oil Natural Gas Casinghead Total Gas (BBLS) (BBLS) (BBLS) (MCF) (MCF) (MCF) 00078 Chevron U.S.A. Inc. 1,926,333,769 137,016,779 2,063,350,548 11,063,925,241 2,504,607,294 13,568,532,535 00689 Shell Offshore Inc. 1,417,893,524 85,274,236 1,503,167,760 7,372,318,798 2,025,230,206 9,397,549,004 00001 Conoco Inc. 797,691,267 90,614,940 888,306,207 6,665,540,300 1,270,468,340 7,936,008,640 00540 MOBIL OIL EXPLORATION & PRODUCING SOUT 323,970,684 67,931,345 391,902,029 6,452,624,776 498,954,383 6,951,579,159 00276 Exxon Mobil Corporation 1,093,558,792 56,026,660 1,149,585,452 5,223,562,198 1,323,290,927 6,546,853,125 00985 Union Exploration Partners, Ltd. 172,994,887 68,962,600 241,957,487 5,693,340,954 248,803,779 5,942,144,733 00081 Tenneco Oil Company 213,224,062 48,335,567 261,559,629 5,587,612,854 279,449,349 5,867,062,203 00040 Texaco Inc. 189,506,674 33,936,036 223,442,710 4,576,194,031 442,571,025 5,018,765,056 00114 Amoco Production Company 97,147,101 34,421,651 131,568,752 3,175,779,982 235,024,436 3,410,804,418 00167 PennzEnergy Company 191,565,059 26,157,422 217,722,481 2,812,024,858 262,674,308 3,074,699,166 00967 Atlantic Richfield Company 242,193,417 18,221,055 260,414,472 -

PENNZOIL-QUAKER STATE REFINERY (A/K/A ATLAS PROCESSING COMPANY)

Health Consultation PENNZOIL-QUAKER STATE REFINERY (a/k/a ATLAS PROCESSING COMPANY) SHREVEPORT, CADDO PARISH, LOUISIANA EPA FACILITY ID: LAD008052334 JUNE 1, 2004 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Health Assessment and Consultation Atlanta, Georgia 30333 Health Consultation: A Note of Explanation An ATSDR health consultation is a verbal or written response from ATSDR to a specific request for information about health risks related to a specific site, a chemical release, or the presence of hazardous material. In order to prevent or mitigate exposures, a consultation may lead to specific actions, such as restricting use of or replacing water supplies; intensifying environmental sampling; restricting site access; or removing the contaminated material. In addition, consultations may recommend additional public health actions, such as conducting health surveillance activities to evaluate exposure or trends in adverse health outcomes; conducting biological indicators of exposure studies to assess exposure; and providing health education for health care providers and community members. This document has previously been released for a 30 day public comment period. Subsequent to the public comment period, ATSDR addressed all public comments and revised or appended the document as appropriate. The health consultation has now been reissued. This concludes the health consultation process for this site, unless additional information is obtained by ATSDR which, -

2008 Annual Report and Form 20-F for the Year Ended December 31, 2008 Contact Information

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC ANNUAL REPORT AND FORM 20-F FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2008 DELIVERY & GROWTH REPORT ANNUAL REPORT AND FORM 20-F FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2008 OUR BUSINESS With around 102,000 employees in more than 100 countries and DOWNSTREAM territories, Shell helps to meet the world’s growing demand for Our Oil Sands business, the Athabasca Oil Sands Project, extracts energy in economically, environmentally and socially bitumen – an especially thick, heavy oil – from oil sands in responsible ways. Alberta, western Canada, and converts it to synthetic crude oils that can be turned into a range of products. UPSTREAM Our Exploration & Production business searches for and recovers Our Oil Products business makes, moves and sells a range of oil and natural gas around the world. Many of these activities petroleum-based products around the world for domestic, are carried out as joint venture partnerships, often with national industrial and transport use. Its Future Fuels and CO2 business oil companies. unit develops biofuels and hydrogen and markets the synthetic fuel and products made from the GTL process. It also leads Our Gas & Power business liquefies natural gas and transports company-wide activities in CO2 management. With around it to customers across the world. Its gas to liquids (GTL) process 45,000 service stations, ours is the world’s largest single-branded turns natural gas into cleaner-burning synthetic fuel and other fuel retail network. products. It develops wind power to generate electricity and is involved in solar power technology. It also licenses our coal Our Chemicals business produces petrochemicals for industrial gasification technology, enabling coal to be used as a chemical customers. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Michigan

5:08-cv-10669-JCO-SDP Doc # 16 Filed 10/14/08 Pg 1 of 12 Pg ID 238 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN PENNZOIL-QUAKER STATE COMPANY, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § Civil Action No. 5:08-cv-10669 § Hon. John Corbett O”Meara LUBEMART ASSOCIATES, INC., § ROBERT HEYL, and JOANN GROSS-HEYL, § § Defendants. § AMENDED CONSENT JUDGMENT The parties have reached agreement on terms of settlement and mutually consent to the following findings of fact, conclusions of law and relief. This Court has considered these findings, conclusions and relief granted and concludes that they are appropriate and should be entered as a final judgment in this action. Based upon all the records herein, the Court makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law: PARTIES AND JURISDICTION 1. Pennzoil-Quaker State Company is a Delaware corporation having its principal place of business at 700 Milam Street, Houston, Texas 77002. 2. Defendant LubeMart Associates, Inc. (“LubeMart”) is a Michigan corporation having a registered office at 32960 Michigan, Wayne, Michigan 48184 and doing business as “LubeMart Associates” at 28915 Telegraph Road, Flat Rock, Michigan 48134 and 32960 West Michigan Ave., Wayne, Michigan 48184. 3. Defendants Robert Heyl and JoAnn Gross-Heyl are individuals who reside in this district and who actively participate in the operation of Defendant LubeMart Associates, Inc. Redline consent2.DOC 5:08-cv-10669-JCO-SDP Doc # 16 Filed 10/14/08 Pg 2 of 12 Pg ID 239 4. This Court has jurisdiction over this action under Section 39 of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C.