Protected Area Assessment and Establishment in Vanuatu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agathis Macrophylla Araucariaceae (Lindley) Masters

Agathis macrophylla (Lindley) Masters Araucariaceae LOCAL NAMES English (pacific kauri); Fijian (da‘ua,dakua dina,makadri,makadre,takua makadre,dakua,dakua makadre) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Agathis macrophylla is a tall tree typically to about 30–40 m tall, 3 m in bole diameter, with a broad canopy of up to 36 m diameter. Branches may be erect to horizontal and massive. Mature specimens have wide, spreading root systems whereas seedlings and young specimens have a vigorous taproot with one or more whorls of lateral roots. Leaves simple, entire, elliptic to lanceolate, leathery, and dark green, and shiny above and often glaucous below; about 7–15 cm long and 2–3.5 cm wide, with many close inconspicuous parallel veins. The leaves taper to a more or less pointed tip, rounded at the base, with the margins curved down at the edge. Petioles short, from almost sessile up to 5 mm long. Cones egg-shaped at the end of the first year, about 5 cm long, and 3 cm in diameter, more or less round at the end of the second year, 8–10 cm in diameter. Female cones much larger than males, globular, on thick woody stalks, green, slightly glaucous, turning brownish during ripening. Seeds brown, small, ovoid to globose, flattened, winged, and attached to a triangular cone scale about 2.5 cm across. BIOLOGY Pacific kauri is monoecious and produces cones instead of flowers. The first female cones begin to be produced at about 10 years old and take up to 2 years to mature (more often in 12-15 months). -

A Study in Ecological Economics

The Process of Forest Conservation in Vanuatu: A Study in Ecological Economics Luca Tacconi December 1995 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of New South Wales I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my . knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher ·learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Luca Tacconi School of Economics and Management University College The University of New South Wales 22 December 1995 With love to my parents Alfi.o and Leda (Con affetto dedico questa tesi ai miei genitori Alfio e Leda) IV Abstract The objective of this thesis is to develop an ecological economic framework for the assessment and establishment of protected areas (PAs) that are aimed at conserving forests and biodiversity. The framework is intended to be both rigorous and relevant to the decision-making process. Constructivism is adopted as the paradigm guiding the research process of the thesis, after firstly examining also positivist philosophy and 'post-normal' scientific methodology. The tenets of both ecological and environmental economics are then discussed. An expanded model of human behaviour, which includes facets derived from institutional economics and socioeconomics as well as aspects of neoclassical economics, is outlined. The framework is further developed by considering, from a contractarian view point, the implications of intergenerational equity for biodiversity conservation policies. -

TORBA Provincial Disaster & Climate Response Plan

PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT COUNCIL PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT OFFICE NATIONAL TORBA ADVISORY BOARD Provincial Disaster & Climate ON CC & DRR Response Plan 2016 Province of TORBA – 2016 PLAN AUTHORIZATION This Plan has been prepared by TORBA Provincial Government Councils in pursuance of Section 11(1) of the National Disaster Act of 2000 and the National Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction Policy. ENDORSED BY: _______________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. Judas Silas Chairperson Provincial Disaster & Climate Change Committee This Plan is approved in accordance with Section 11(2) of the National Disaster Act 2000 and is in-line with the National Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction Policy 2015-2030. APPROVED BY: ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. Shadrack Welegtabit Director National Disaster Management Office Ministry Of Climate Change and Disasters ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Mr. David Gibson Director VMGD Office Ministry Of Climate Change and Disasters ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Ms Anna Bule Secretariat National Advisory Board on Climate Change & Disaster Risk Reduction ___________________ Date: / / 2016 Ms Ketty Napwatt Secretary General TORBA Provincial Government i | Province of TORBA – 2016 PREFACE Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Provincial level is a dynamic process. In order to adequately respond to disasters, there must be a comprehensive and coordinated approach between national, provincial and community levels. This plan has been developed to provide guidelines on how to manage different risks in the province, taking into account the effects of the climate change that increase the strength of the hazard and potential impacts of future disasters. This Provincial Disaster & Climate Response Plan provides directive to all agencies on the conduct of Disaster Preparedness and Emergency operations. -

Republic of Fiji: the State of the World's Forest Genetic Resources

REPUBLIC OF FIJI This country report is prepared as a contribution to the FAO publication, The Report on the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources. The content and the structure are in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines given by FAO in the document Guidelines for Preparation of Country Reports for the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources (2010). These guidelines set out recommendations for the objective, scope and structure of the country reports. Countries were requested to consider the current state of knowledge of forest genetic diversity, including: Between and within species diversity List of priority species; their roles and values and importance List of threatened/endangered species Threats, opportunities and challenges for the conservation, use and development of forest genetic resources These reports were submitted to FAO as official government documents. The report is presented on www. fao.org/documents as supportive and contextual information to be used in conjunction with other documentation on world forest genetic resources. The content and the views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the entity submitting the report to FAO. FAO may not be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this report. STATE OF THE FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES IN FIJI Department of Forests Ministry of Fisheries and Forests for The Republic of Fiji Islands and the Secreatriat of Pacific Communities (SPC) State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executve Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 5 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 6 Chapter 1: The Current State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji ………………………………………………………………….……. -

The Mosquitoes of the Banks and Torres Island Groups of the South Pacific (Diptera: Culicidae)

Vol. 17, no. 4: 511-522 28 October 1977 THE MOSQUITOES OF THE BANKS AND TORRES ISLAND GROUPS OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC (DIPTERA: CULICIDAE) By Mario Maffi1 and Brian Taylor2 Abstract: In August 1971 a total of 1003 specimens of Culicidae were collected from 2 little known island groups ofthe New Hebrides, the Banks and the Torres, 637 (39 $$, 12 S$, 148 P, 13 p, 419 L, 6 1) and 366 (46 $$, 3 $<$, 73 P, 13 p, 231 L), respectively. Of 9 species of Culicidae previously recorded, 6 are confirmed. 3 species are added: Culex (Cux.) banksensis, Culex {Cux,) sitiens, Culex (Eum.) Jemineus. The distribution (considerably wider than previously recorded) and the bionomics of the species are presented. Located at the northern end of the territory of the New Hebrides Condominium, and administratively part of it, 2 island groups, the Banks and the Torres, rise from the New- Hebrides submarine ridge and are dispersed over a wide area of the Southwest Pacific: 13°04' to 14°28' S, and 166°30' to 168°04' E. The Banks, the southern ofthe 2 groups, are more scattered and consist of 2 major islands (Gaua, Vanua Lava) and 6 minor islands (Merelava, Merig, Mo ta, Motalava, Parapara, Ro wa) with a total land area of approx imately 750 km2. The Torres group is more compact and consists of 5 small islands (Toga, Loh, Tegua, Metoma, Hiu) with less than 100km2 ofland area. There are a few off-shore islets. Except for the reef island of Rowa, the islands are of volcanic origin; however, on some of the smaller islands, particularly in the Torres, there are terraces of coral limestone. -

Summary Report on Forests of the Mataqali Nadicake Kilaka, Kubulau District, Bua, Vanua Levu

SUMMARY REPORT ON FORESTS OF THE MATAQALI NADICAKE KILAKA, KUBULAU DISTRICT, BUA, VANUA LEVU By Gunnar Keppel (Biology Department, University of the South Pacific) INTRODUCTION I was approached by Dr. David Olson of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) to assess the type, status and quality of the forest in Kubulau District, Bua, Vanua Levu. I initially spent 2 days, Friday (28/10/2005) afternoon and the whole of Saturday (29/10/2005), in Kubulau district. This invitation was the result of interest by some landowning family clans (mataqali) to protect part of their land and the offer by WCS to assist in reserving part of their land for conservation purposes. On Friday I visited two forest patches (one logged about 40 years ago and another old-growth) near the coast and Saturday walking through the forests in the center of the district. Because of the scarcity of data obtained (and because the forest appeared suitable for my PhD research), I decided to return to the district for a more detailed survey of the northernmost forests of Kubulau district from Saturday (12/11/2005) to Tuesday (22/11/2005). Upon returning, I found out that the mataqali Nadicake Nadi had abandoned plans to set up a reserve and initiated steps to log their forests. Therefore, I decided to focus my research on the land of the mataqali Nadicake Kilaka only. My objectives were the following: 1) to determine the types of vegetation present 2) to produce a checklist of the flora and, through this list, identify rare and threatened species in the reserve 3) to undertake a quantitative survey of the northernmost forests (lowland tropical rain forest) by setting up 4 permanent 50 ×50m plots 4) to assess the status of the forests 5) to determine the state and suitability of the proposed reserve 6) to assess possible threats to the proposed reserve. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2012-2013)

IUCN Red List version 2013.2: Table 7 Last Updated: 25 November 2013 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2012-2013) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2012 (IUCN Red List version 2012.2) and 2013 (IUCN Red List version 2013.2) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.) IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2012) List (2013) change version Category Category MAMMALS Nycticebus javanicus Javan Slow Loris EN CR N 2013.2 Okapia johnstoni Okapi NT EN N 2013.2 Pteropus niger Greater Mascarene Flying -

Types of Vegetation Occuring on Santo

in BOUCHET P., LE GUYADER H. & PASCAL O. (Eds), The Natural History of Santo. MNHN, Paris; IRD, Marseille; PNI, Paris. 572 p. (Patrimoines naturels; 70). Types of Vegetation Occurring on Santo Jérôme Munzinger, Porter P. Lowry II & Jean-Noël Labat The Santo 2006 expedition was Table 5: Vegetation types in Vanuatu proposed by Mueller- designed to carry out detailed explo- Dombois and Fosberg. ration of the botanical diversity 1. Lowland rain forest present on the island. A wide diver- sity of vegetation types were there- a. High-stature forests on old volcanic ash fore studied, covering the full range b. Medium-stature forest heavily covered with lianas extending from what can be regarded c. Complex forest scrub densely covered with lianas as "extremes" on a scale from natu- d. Alluvial and floodplain forests ral, nearly undisturbed areas to those e. Agathis-Calophyllum forest that have been profoundly modified f. Mixed-species forests without gymnosperms and by man. Large areas have been trans- Calophyllum formed by humans — partially or completely — through clearing, fire, 2. Montane cloud forest and related vegetation Principal and other means, in an effort to meet basic needs for food, shelter, fiber, 3. Seasonal forest, scrub and grassland grazing land for livestock, etc., although such a. Semi-deciduous transitions forests habitats exist only because they are created and b. Acacia spirorbis forest maintained by man or by domesticated animals. c. Leucaena thicket, savanna and grassland At the other extreme, Santo’s vegetation includes nearly pristine formations that result from the 4. Vegetation on new volcanic surfaces natural processes of evolution and succession and are self-maintaining, provided they are not subject 5. -

CEPF Final Project Completion Report

CEPF Final Project Completion Report Instructions to grantees: please complete all fields, and respond to all questions, below. Organization Legal Name Live & Learn Vanuatu Education for Action: Empowering Local Communities for Project Title Biodiversity Conservation at CEPF Priority Sites in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu CEPF GEM No. 64252 Date of Report December 2015 Report Author Anjali Nelson & Jessie Kampai [email protected], [email protected] Author Contact Information +678 27455 CEPF Region: Eastern Melanesian Islands Strategic Direction: Strategic direction 1: Empower local communities to protect and manage globally significant biodiversity at priority Key Biodiversity Areas under-served by current conservation efforts. Grant Amount: USD 99,990 Project Dates: 01/05/2014 – 30/04/2015 (given 6 month extension due to cyclone to 31/10/2015) 1. Implementation Partners for this Project (list each partner and explain how they were involved in the project) Live & Learn Solomon Islands (a local partner). The partner has an affiliate agreement with the other Live & Learn offices and will work closely with Live & Learn Vanuatu (LLV) as part of the project team. Live & Learn Solomon Islands implemented educational activities in East Rennell as an initial phase of the project. Live & Learn International was a second project partner. The inception workshop, printing and disbursement of resources was supported through the Australian office. Conservation Impacts 2. Describe how your project has contributed to the implementation of the CEPF ecosystem profile This project served to support Strategic Direction 1 by empowering local communities to undertake conservation actions through education and participatory planning. Site locations for the project fell within the priority sites identified by the Ecosystem Profile and focused on communities within these sites that were underserved by other conservation efforts in the broader geographic area. -

Tanna Island - Wikipedia

Tanna Island - Wikipedia Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Tanna Island From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 19°30′S 169°20′E Tanna (also spelled Tana) is an island in Tafea Main page Tanna Contents Province of Vanuatu. Current events Random article Contents [hide] About Wikipedia 1 Geography Contact us 2 History Donate 3 Culture and economy 3.1 Population Contribute 3.2 John Frum movement Help 3.3 Language Learn to edit 3.4 Economy Community portal 4 Cultural references Recent changes Upload file 5 Transportation 6 References Tools 7 Filmography Tanna and the nearby island of Aniwa What links here 8 External links Related changes Special pages Permanent link Geography [ edit ] Page information It is 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 19 Cite this page Wikidata item kilometres (12 miles) wide, with a total area of 550 square kilometres (212 square miles). Its Print/export highest point is the 1,084-metre (3,556-foot) Download as PDF summit of Mount Tukosmera in the south of the Geography Printable version island. Location South Pacific Ocean Coordinates 19°30′S 169°20′E In other projects Siwi Lake was located in the east, northeast of Archipelago Vanuatu Wikimedia Commons the peak, close to the coast until mid-April 2000 2 Wikivoyage when following unusually heavy rain, the lake Area 550 km (210 sq mi) burst down the valley into Sulphur Bay, Length 40 km (25 mi) Languages destroying the village with no loss of life. Mount Width 19 km (11.8 mi) Bislama Yasur is an accessible active volcano which is Highest elevation 1,084 m (3,556 ft) Български located on the southeast coast. -

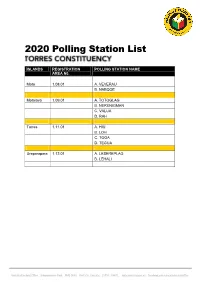

2020 Polling Station List

2020 Polling Station List ISLANDS REGISTRATION POLLING STATION NAME AREA N0. Mota 1.08.01 A. VEVERAU B. NABQOE Motalava 1.09.01 A. TOTOGLAG B. NERENIGMAN C. VALUA D. RAH Torres 1.11.01 A. HIU B. LOH C. TOGA D. TEGUA Ureparapara 1.12.01 A. LESEREPLAG B. LEHALI Vanuatu Electoral Office. Independence Park. PMB 9033. Port Vila, Vanuatu. 23914 / 33470. www.electoral.gov.vu facebook.com/vanuatuelectoraloffice ISLANDS REGISTRATION POLLING STATION AREA N0. Merelava 1.07.01 A. LEKWEL B. TASMAT C. AOTA Santa 1.10.01 A. NAMASARI Maria Merig B. LEMANMAN C. MERIG D. KORO Gaua 1.10.02 A. ONTAR B. LEMBAL C. MAKEON Vanualava 1.13.02 A. SOLA B. MOSINA C. MERELAEN D. VATOP E. LION BAY Vanualava 1.13.02 A. VATRATA B. VETIMBOSO C. WOSAGA Vanuatu Electoral Office. Independence Park. PMB 9033. Port Vila, Vanuatu. 23914 / 33470. www.electoral.gov.vu facebook.com/vanuatuelectoraloffice REGISTRATION AREA NO. LETTER/POLLING STATIONS 1.03.01 A. PORT OLRY 1.03.02 A. HOGHABOUR B. SHARKBAY C. LORETIAKARKAR D. LOREVULKO 1.03.03 A. MATANTAS B. MALAU C. JEREVIU D. PIALUPLUP E. PIAMATSINA F. PESENA G. MALOVUKO H. TOLOMAKO I. PIAVOT J. PELVUS K. MALJEA 1.03.04 A. WUNPOKO B. BETHANY C. NOKUGU D. VUNAVAE E. TASMAT F. WUSI G. SULEMAURI H. RAVLEPA I. OLPOI 1.03.05 A. TASSIRIKI B. IPAYATO C. PELMOLI D. KEREVALIS 1.03.06 A. ARAKI B. TASMALUM Vanuatu Electoral Office. Independence Park. PMB 9033. Port Vila, Vanuatu. 23914 / 33470. www.electoral.gov.vu facebook.com/vanuatuelectoraloffice C. -

Roosting Ecology of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox: Spatial Dispersion in a Summer Camp

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2002 Roosting Ecology of the Grey-headed Flying Fox: Spatial Dispersion in a Summer Camp Jennifer L. Holmes University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Holmes, Jennifer L., "Roosting Ecology of the Grey-headed Flying Fox: Spatial Dispersion in a Summer Camp. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2002. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2067 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Jennifer L. Holmes entitled "Roosting Ecology of the Grey-headed Flying Fox: Spatial Dispersion in a Summer Camp." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Gary F. McCracken, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Gordon M. Burghardt, Dewey Bunting Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: We are submitting herewith a thesis written by Jennifer Holmes entitled “Roosting Ecology of the Grey-headed Flying Fox: Spatial Dispersion in a Summer Camp.” We have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.