The New Aural Actuality: an Exploration of Music, Sound And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Autoethnography of Scottish Hip-Hop: Identity, Locality, Outsiderdom and Social Commentary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Napier An autoethnography of Scottish hip-hop: identity, locality, outsiderdom and social commentary Dave Hook A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Declaration This critical appraisal is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It has not been previously submitted, in part or whole, to any university or institution for any degree, diploma, or other qualification. Signed:_________________________________________________________ Date:______5th June 2018 ________________________________________ Dave Hook BA PGCert FHEA Edinburgh i Abstract The published works that form the basis of this PhD are a selection of hip-hop songs written over a period of six years between 2010 and 2015. The lyrics for these pieces are all written by the author and performed with hip-hop group Stanley Odd. The songs have been recorded and commercially released by a number of independent record labels (Circular Records, Handsome Tramp Records and A Modern Way Recordings) with worldwide digital distribution licensed to Fine Tunes, and physical sales through Proper Music Distribution. Considering the poetics of Scottish hip-hop, the accompanying critical reflection is an autoethnographic study, focused on rap lyricism, identity and performance. The significance of the writing lies in how the pieces collectively explore notions of identity, ‘outsiderdom’, politics and society in a Scottish context. Further to this, the pieces are noteworthy in their interpretation of US hip-hop frameworks and structures, adapted and reworked through Scottish culture, dialect and perspective. -

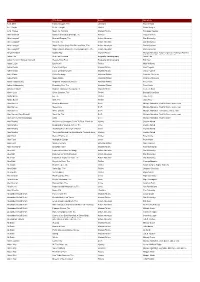

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

TAL Distribution Press Release

This American Life Moves to Self-Distribute Program Partners with PRX to Deliver Episodes to Public Radio Stations May 28, 2014 – Chicago. Starting July 1, 2014, Chicago Public Media and Ira Glass will start independently distributing the public radio show This American Life to over 500 public radio stations. Episodes will be delivered to radio stations by PRX, The Public Radio Exchange. Since 1997, the show has been distributed by Public Radio International. “We’re excited and proud to be partners now with PRX,” said Glass. “They’ve been a huge innovative force in public radio, inventing technologies and projects to get people on the air who’d have a much harder time without them. They’re mission- driven, they’re super-capable and apparently they’re pretty good with computers.” “We are huge fans of This American Life and are thrilled to support their move to self-distribution on our platform,” said Jake Shapiro, CEO of PRX. “We’ve had the privilege of working closely with Ira and team to develop This American Life’s successful mobile apps, and are honored to expand our partnership to the flagship broadcast.” This American Life will take over other operations that were previously handled by PRI, including selling underwriting and marketing the show to stations. The marketing and station relations work will return to Marge Ostroushko, who did the job back before This American Life began distribution with PRI. This American Life, produced by Chicago Public Media and hosted by Ira Glass, is heard weekly by 2.2 million people over the radio. -

A – Z Internet Resources for Education A

A – Z Internet Resources for Education A o Acapela.tv is a fun site to create text-to-speech animations. o Alice is a 3D programming environment that makes it easy to create an animation for telling a story, playing an interactive game, or a video to share on the web. Alice is a teaching tool for introductory computing. It uses 3D graphics and a drag-and-drop interface to facilitate a more engaging, less frustrating first programming experience. o Animoto.com is a web application that produces professional quality videos from your pictures and music. o Audacity is a programme that allows you to record sounds straight to your computer (you do need a microphone) and edit them afterwards. Very popular with languages teachers and podcasters. o Audioboo is an audio-blogging site, you can send in updates through the web, phone or its own iPhone app. Perfect for blogging on the move, like on a school-trip, or sharing your class’s opinion about a topic. o authorSTREAM allows you to publish and share your PowerPoint presentations. It also allows you to download published presentations as videos. o Aviary is a suite of web applications which allow you to create, edit and manipulate images. They have also recently launched an audio editing tool called Myna (see below). B o BeFunky is a website that allows you to apply a variety of fun effects to your own photos or from photo sharing sites. o Big Huge Labs is a collection of utilities and toys that allow you to edit and alter digital pictures. -

Episode 58: the Whole Shabang Air Date: May 12, 2021

Episode 58: The Whole Shabang Air Date: May 12, 2021 [in the field – at Lancaster State Prison, outdoors, voices chattering in the background] Mike Oog: My name is Mike Oog and I've been incarcerated twenty-nine years. Nigel Poor: OK, “The following episode of Ear Hustle…” Mike: [repeating after Nigel] The following episode of Ear Hustle… Nigel: “Contains language that may not be appropriate for all listeners.” Mike: Contains language that may not be appropriate for all listeners. Nigel: “Discretion is advised.” Mike: Discretion is advised. Nigel: And can you say where you're standing right now? 1 Mike: I'm standing in front of the program office at LAC, Lancaster State Prison. [strong wind picks up] Nigel: Oooh! Speaker 1: Watch your eyes! Oh yeah, [theme music comes in] that's a dust storm. [voices chattering in the background, reacting to dust and wind] We just got dusted. This is the Mojave Desert and we just got dusted. Nigel: Wow. That hurt. [as narrator, to Earlonne] Nigel: Oof, Earlonne, that was not like being at San Quentin. Earlonne Woods: Nah… I haven't been in heat like that in so long to where I forgot my hat. [Nigel laughs] Nigel: I know. But, OK, you didn’t have your hat, but you were dressed up that day. Earlonne: Oh! Any time I step back in a penal system, [Nigel laughs] I'm gonna be suited and booted. You know what I'm saying? I gotta inspire cats. Nigel: Right! Success walks back in, right? [Nigel laughs] Earlonne: Indeed. -

The Sirens Call Ezine Throughout the Years

1 Table of Contents pg. 04 - The Cave| H.B. Diaz pg. 110 - Mud Baby | Lori R. Lopez pg. 07 - Honeysuckle | T.S. Woolard pg. 112 - On Eternity’s Brink | Lori R. Lopez pg. 08 - Return to Chaos | B. T. Petro pg. 115 - Sins for the Father | Marcus Cook pg. 08 - Deathwatch | B. T. Petro pg. 118 - The Island | Brian Rosenberger pg. 09 - A Cup of Holiday Cheer | KC Grifant pg. 120 - Old John | Jeffrey Durkin pg. 12 - Getting Ahead | Kevin Gooden pg. 123 - Case File | Pete FourWinds pg. 14 - Soup for Mother | Sharon Hajj pg. 124 - Filling in a Hole | Radar DeBoard pg. 15 - A Dying Moment | Gavin Gardiner pg. 126 - Butterfly | Lee Greenaway pg. 17 - Snake | Natasha Sinclair pg. 130 - Death’s Gift | Naching T. Kassa pg. 19 - The Cold Death | Nicole Henning pg. 132 - Waste Not | Evan Baughfman pg. 21 - The Burning Bush | O. D. Hegre pg. 132 - Rainbows and Unicorns | Evan Baughfman pg. 24 - The Wishbone | Eileen Taylor pg. 133 - Salty Air | Sonora Taylor pg. 27 - Down by the River Walk | Matt Scott pg. 134 - Death is Interesting | Radar DeBoard pg. 30 - The Reverend I Milkana N. Mingels pg. 134 - It Wasn’t Time | Radar DeBoard pg. 31 - Until Death Do Us Part | Candace Meredith pg. 136 - Future Fuck | Matt Martinek pg. 33 - A Grand Estate | Zack Kullis pg. 139 - The Little Church | Eduard Schmidt-Zorner pg. 36 - The Chase | Siren Knight pg. 140 - Sweet Partings | O. D. Hegre pg. 38 - Darla | Miracle Austin pg. 142 - Christmas Eve on the Rudolph Express | Sheri White pg. 39 - I Remember You | Judson Michael Agla pg. -

Just Announced

JUST ANNOUNCED Aldous Harding Wed 30 & Thu 31 Mar 2022, Barbican Hall, 8pm Tickets £20 – £25 New Zealand singer-songwriter Aldous Harding, alongside her band, makes her Barbican debut in March 2022. The two shows will feature material from her three studio albums to date. Harding, whose music has been described as ‘disquietingly beautiful and unsettling as her image’ by the Guardian, drew critical acclaim for the gothic indie folk style on her eponymous self-titled 2014 debut album. Her two follow-up albums – 2017’s Party and 2019's Designer – were released on British independent label 4AD. Both records were co-produced by John Parish (PJ Harvey, Sparklehorse). John Parish also produced Harding’s track Old Peel – known and loved by fans as the set-closer at her most recent live shows – which will be digitally released on 15 June and as a limited 7” on 9 July 2021. Aldous Harding was awarded a prestigious Silver Scroll Award for The Barrel (the New Zealand equivalent of the Ivor Novellos) and was nominated in the Solo Artist category in 2020’s Q Awards. Designer also made the top 5 in Mojo's 2019 Best Albums of the Year. Touring extensively pre-pandemic, Harding is renowned for the captivating state of possession she occupies in live performances, winning over audiences across the world. Produced by the Barbican in association with Bird On The Wire On sale to Barbican patrons and members on Wed 16 Jun 2021 On general sale on Fri 18 Jun 2021 Find out more FURTHER EVENT DETAILS ANNOUNCED George the Poet: Live from the Barbican Thu 1 Jul 2021, Barbican Hall, 8pm Tickets £20 – 30 & £12.50 (livestream) George the Poet will bring his innovative brand of musical poetry to Live from the Barbican this summer. -

Ebury Publishing Spring Catalogue 2019

EBURY PUBLISHING SPRING CATALOGUE 2019 The Healing Self Supercharge your immune system and stay well for life Deepak Chopra with Rudolph E Tanzi Combining the best current medical knowledge with a new approach grounded in integrative medicine, Dr Chopra and Dr Tanzi offer a groundbreaking model of healing and the immune system. Heal yourself from the inside out Our immune systems can no longer be taken for granted. Current trends in public healthcare are disturbing: our increased air travel allows newly mutated bacteria and viruses to spread across the globe, antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria outstrip the new drugs that are meant to fight them, deaths due to hospital-acquired infections are increasing, and the childhood vaccinations of our aging population are losing their effectiveness. Now more than ever, our well-being is at a dangerous crossroad. But there is hope, and the solution lies within ourselves. The Healing Self is the new breakthrough book in self-care by bestselling author and leader in integrative medicine Deepak Chopra and Harvard neuroscientist Rudolph E Tanzi. They argue that the brain possesses its own lymphatic system, meaning it is also tied into the body’s general immune system. Based on this brand new discovery, they offer new ways of January 2019 increasing the body’s immune system by stimulating the brain 9781846045714 and our genes, and through this they help us fight off illness £6.99 : Paperback and disease. Combined with new facts about the gut 304 pages microbiome and lifestyle changes, diet and stress reduction, there is no doubt that this ground-breaking work will have an important effect on your immune system. -

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

Chamber Music Concerts Player and Chamber Musician with the Tempest Two Concerts Featuring Rounds for Brass Quintet, Flute Trio

We are Chamber Music We are Opera and Song We are Popular Music Our Chamber Music Festival goes to the city Again in Manchester Cathedral, we will be Following its success at the Royal Albert Hall and Welcome centre (10-12 Jan) using Manchester Cathedral taking the magic and mystery of Orpheus with here at the RNCM last term, the RNCM Session as our hub, and featuring the Academy of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (28 Mar), which Orchestra returns with an exciting eclectic Ancient Music, the Talich Quartet and The will also be performed alongside his witty programme (25 Apr). Staff-led Vulgar Display Band of Instruments together with our staff The Drunkard Cured (L’ivrogne corrigé) in our give us their take on extreme metal (12 Feb). to the and students, to explore ‘The Art of Bach’. exclusive double-bill in the intimacy of our Our faithful lunchtime concert followers need not worry about the temporary closure of our Studio Theatre (18, 20, 22 and 27 Mar). Opera We are Folk and World Spring Concert Hall. These concerts will be as frequent, Scenes are back (21, 24, 28 and 31 Jan), as Fusing Latin American and traditional Celtic diverse and delightful as ever, in fantastic venues entertaining as ever. Yet another exciting venture folk, Salsa Celtica appear on the RNCM stage such as the Holden Art Gallery, St Ann’s is the one with the Royal Exchange Theatre for (7 Mar), followed by loud, proud acoustic season at Church and the Martin Harris Centre, featuring an extra-indulgent Day of Song (27 Apr) where Bellowhead–founding members, Spiers & the RNCM Chamber Ensemble with Stravinsky’s we will be taking you with us through the lush Boden on their last tour as a duo (20 Mar), The Soldier’s Tale, as well as a feast of other atmosphere of the Secession and travelling from while the award-winning folk band Melrose ensembles: Harp, Saxophone, Percussion and country to country by song throughout the day. -

Stories Told Through Sound

STORIES TOLD THROUGH SOUND - - - - - - - - - - - BBC Spotify Tate Modern BBC BBC Airbnb Audible BBC Unherd BBC Sounds Gorrilaz Radio 4 Radio 3 World Service 1 Great stories speak for themselves; We travel the world in search of they don’t need to be dressed up stories that matter: whether it’s or dumbed down. Tell them with current affairs, health, sport, food, passion, care, commitment and science or religion – if the story integrity and people will listen. So is worth telling, we want to be the that’s what we do – tell the stories ones to do it. And it seems that our people need to hear, in a way that approach is working: in the three WHO WE ARE makes them listen. short years since our launch we’ve built an impressive portfolio of SPG is one of the UK’s leading work, having made award-winning independent audio production podcasts and radio programmes for companies. We make inspiring some of the biggest broadcasters, story-first content based on rigorous platforms and commercial partners in journalistic principles and meticulous the world. production values. Our team of journalists and producers know what - it takes to tell an engaging story and have the skills to deliver an THE exceptional product every time. - DIFFERENCE WHEN YOU BETWEEN TELL GREAT HEARING AND STORIES, LISTENING PEOPLE PAY Taking on China - UnHerd - 2017 ATTENTION. 2 It’s Obscene! - Radio 4 - 2016 FAST-GROWING, WIDE INTERESTS AND RETAINED AUDIENCE APPETITES, SHAPED BY ON-DEMAND BEHAVIOUR Podcasts listened 10m to every week Look for new 59% podcasts each WHO IS week Listen everyday 1.1m COMMITTED, DIGITAL, LISTENING? ON-THE-MOVE Average time YOUNG, DIVERSE spent listening DEMOGRAPHICS 6.7hrs to podcasts each Podcasts are the ideal format to communicate a brand’s core messages and values.