Perspectives from the Split-Share Structure Reform$

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

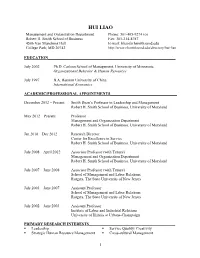

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (O) Robert H

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (o) Robert H. Smith School of Business Fax: 301-214-8787 4506 Van Munching Hall E-mail: [email protected] College Park, MD 20742 http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/directory/hui-liao EDUCATION_________________________________________________________________ July 2002 Ph.D. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota Organizational Behavior & Human Resources July 1997 B.A. Renmin University of China International Economics ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS__________________________________ December 2012 – Present Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland May 2012 – Present Professor Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 Research Director Center for Excellence in Service Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2008 – April 2012 Associate Professor (with Tenure) Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2007 – June 2008 Associate Professor (with Tenure) School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2003 – June 2007 Assistant Professor School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2002 – June 2003 Assistant Professor Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS____________________________________________ . Leadership . Service Quality/ Creativity . Strategic Human Resource Management . Cross-cultural Management 1 MAJOR SCHOLARLY AWARDS AND HONORS__________________________________ . 2012, Named an endowed professorship – Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland . 2012, Cummings Scholarly Achievement Award, OB Division, Academy of Management . -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University. -

Liang Feng Associate Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology Molecular & Cellular Physiology

Liang Feng Associate Professor of Molecular and Cellular Physiology Molecular & Cellular Physiology Bio ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS • Associate Professor, Molecular & Cellular Physiology • Member, Bio-X HONORS AND AWARDS • NIH Director's New Innovator Award, NIH (2015) • Klingenstein-Simons Fellow, The Klingenstein Fund and the Simons Foundation (2015) • Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (2014) PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION • PhD, Princeton University (2006) • MPhil, HKUST (2002) • B.S., Tsinghua University (1999) LINKS • Lab stie (under construction): https://sites.google.com/site/fenggroupatstanford/ Research & Scholarship CURRENT RESEARCH AND SCHOLARLY INTERESTS Biological membranes act as selective barriers that separate the interior of cells from their outside environment. Membrane proteins play crucial roles in a wide range of biological and physiological processes and are targeted by a large number of pharmacologically active compounds including ~ 50% of the drugs in use today. Lack of high-resolution structural information has become a bottleneck for the mechanistic understanding of membrane proteins and hinders potential drug development. Our research interest lies primarily in understanding the mechanism and regulation of these dynamic membrane proteins, and developing small molecule modulators based on their structures and functions. We are taking a multi-disciplinary approach, employing structural methods to capture the high-resolution picture of different states, functional assays and biophysical methods to dissect -

Light on the Liao

A photo essay LIGHT ON THE LIAO n summer 2009, I was fortunate to participate in a summer seminar, ”China’s Northern Frontier,” co-sponsored I by the Silkroad Foundation, Yale University and Beijing University. Lecturers included some of the luminaries in the study of the Liao Dynasty and its history. In traveling through Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia and Lia- K(h)itan Abaoji in what is now Liaoning Province. At its peak, the Liao Empire controlled much of North China, Mongolia and territories far to the West. When it fell to the Jurchen in 1125, its remnants re-emerged as the Qara Khitai off in Central Asia, where they survived down to the creation of the Mongol empire (for their history, see the pioneering monograph by Michal Biran). While they began as semi-nomadic pastoralists, the Kitan/Liao in recent years from Liao tombs attest to their involvement in international trade and the sophistication of their cultural achievements. As with other states established in “borderlands” they drew on many different sources to create a distinctive culture which is now, after long neglect, being fully appreciated. These pictures touch but a few high points, leaving much else for separate exploration, which, it is hoped, they will stimulate readers to undertake on their own. The history and culture of the Kitan/Liao merit your serious attention, forming as they do an important chapter in the larger history of the silk roads. With the exception of the map and satellite image, the photos are all mine, a very few taken in collections outside of China, but the great majority during the seminar in 2009. -

Multi-Task Learning for Classification with Dirichlet Process Priors

Journal of Machine Learning Research 8 (2007) 35-63 Submitted 4/06; Revised 9/06; Published 1/07 Multi-Task Learning for Classification with Dirichlet Process Priors Ya Xue [email protected] Xuejun Liao [email protected] Lawrence Carin [email protected] Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Duke University Durham, NC 27708, USA Balaji Krishnapuram [email protected] Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc. Malvern, PA 19355, USA Editor: Peter Bartlett Abstract Consider the problem of learning logistic-regression models for multiple classification tasks, where the training data set for each task is not drawn from the same statistical distribution. In such a multi-task learning (MTL) scenario, it is necessary to identify groups of similar tasks that should be learned jointly. Relying on a Dirichlet process (DP) based statistical model to learn the extent of similarity between classification tasks, we develop computationally efficient algorithms for two different forms of the MTL problem. First, we consider a symmetric multi-task learning (SMTL) situation in which classifiers for multiple tasks are learned jointly using a variational Bayesian (VB) algorithm. Second, we consider an asymmetric multi-task learning (AMTL) formulation in which the posterior density function from the SMTL model parameters (from previous tasks) is used as a prior for a new task: this approach has the significant advantage of not requiring storage and use of all previous data from prior tasks. The AMTL formulation is solved with a simple Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) construction. Experimental results on two real life MTL problems indicate that the proposed algorithms: (a) automatically identify subgroups of related tasks whose training data appear to be drawn from similar distributions; and (b) are more accurate than simpler approaches such as single-task learning, pooling of data across all tasks, and simplified approximations to DP. -

A Hypothesis on the Origin of the Yu State

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 139 June, 2004 A Hypothesis on the Origin of the Yu State by Taishan Yu Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Comment On: “A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of Medical Big Data Research” Sustainability 2018, 10, 166

sustainability Comment Comment on: “A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of Medical Big Data Research” Sustainability 2018, 10, 166 Yuh-Shan Ho Trend Research Centre, Asia University, No. 500, Lioufeng Road, Wufeng, Taichung County 41354, Taiwan; [email protected] Received: 25 November 2018; Accepted: 18 December 2018; Published: 19 December 2018 Liao et al. recently published a paper in this journal entitled “A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of Medical Big Data Research” [1]. In “Section 2. Data and Methods”, the authors specified the following: ‘We took ”medical big data” as topical retrieval and the time span was defined as “all years” (However, according to the returned results, we know that the first publication in MBD was appeared in 1991). The literature type was defined as “all types”. In total, 988 documents met the selection criteria. Ten document types were found in these 988 publications.’ To check results in the original paper [1], we searched the Clarivate Analytics Web of Science, the online version of the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED), and the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) on 2 November 2018. The databases were searched using the keywords “medical big data” in terms of topic (title, abstract, author keywords, and KeyWords Plus) within the publication years of 1900 to 2017. Only 18 documents could be found, including 15 articles, two meeting abstracts, and one editorial material but not “988 documents” as mentioned in the original paper [1]. The 15 medical big data-related articles were published by Al Hamid et al. [2], Azar and Hassanien [3], Chen et al. -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr. -

Surname Methodology in Defining Ethnic Populations : Chinese

Surname Methodology in Defining Ethnic Populations: Chinese Canadians Ethnic Surveillance Series #1 August, 2005 Surveillance Methodology, Health Surveillance, Public Health Division, Alberta Health and Wellness For more information contact: Health Surveillance Alberta Health and Wellness 24th Floor, TELUS Plaza North Tower P.O. Box 1360 10025 Jasper Avenue, STN Main Edmonton, Alberta T5J 2N3 Phone: (780) 427-4518 Fax: (780) 427-1470 Website: www.health.gov.ab.ca ISBN (on-line PDF version): 0-7785-3471-5 Acknowledgements This report was written by Dr. Hude Quan, University of Calgary Dr. Donald Schopflocher, Alberta Health and Wellness Dr. Fu-Lin Wang, Alberta Health and Wellness (Authors are ordered by alphabetic order of surname). The authors gratefully acknowledge the surname review panel members of Thu Ha Nguyen and Siu Yu, and valuable comments from Yan Jin and Shaun Malo of Alberta Health & Wellness. They also thank Dr. Carolyn De Coster who helped with the writing and editing of the report. Thanks to Fraser Noseworthy for assisting with the cover page design. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A Chinese surname list to define Chinese ethnicity was developed through literature review, a panel review, and a telephone survey of a randomly selected sample in Calgary. It was validated with the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Results show that the proportion who self-reported as Chinese has high agreement with the proportion identified by the surname list in the CCHS. The surname list was applied to the Alberta Health Insurance Plan registry database to define the Chinese ethnic population, and to the Vital Statistics Death Registry to assess the Chinese ethnic population mortality in Alberta. -

Translation of Names and Comparison of Addressing Between Chinese and English from the Intercultural Perspective

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 9, pp. 1227-1230, September 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.9.1227-1230 Translation of Names and Comparison of Addressing between Chinese and English from the Intercultural Perspective Xueqing Wang Department of Fundamental Course, Zhenjiang Watercraft College of PLA, Zhenjiang, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—It is self-evident that to communicate, we must first know the participants’ names, or successful communication will be impossible. Names not only symbolize identities, but also denote special significance such as the great expectation from the parents. It is absolutely impolite and embarrassing to make mistakes in regard to others’ names. Therefore, it is of staggering significance in communication, especially in intercultural one. With the deepening project of reform and opening up to the outside world, frequent intercultural communications take place. Because the structure of people’s names in English-speaking countries is different from ours, it is extremely important to correctly translate foreign names and name foreigners. Only when we are aware of the differences can we carry out smooth intercultural communication. In this article, I will analyze these phenomena. Index Terms—translation, names, addressing, English, Chinese I. INTRODUCTION There have been lots of fervent discussions on translation of names. In regard to the translation of names from Chinese into English, Chinese phonetic system has been used since 1978. But in fact, many overseas Chinese students, Chinese visiting scholars and people living in Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR and Taiwan province conduct their own practices. -

About Chinese Names

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 130 Article 4 6-1-2003 About Chinese Names Sheau-yueh Janey Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh Janey (2003) "About Chinese Names," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 130 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss130/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CHINESE NAMES sheau yueh janey chao baruch college city university new york introduction traditional chinese society family chia clan tsu play indispensable role establishing sustaining prevailing value system molding life individuals shaping communitys social relations orderly stable pattern lin 1959 clan consolidating group organized numerous components family members traced patrilineal descent common ancestor first settled given locality composed lines genealogical lineage bearing same family name therefore family name groups real substance clan formed chen 1968 further investigation origin development spread chinese families population genealogical family name materials essential study reason why anthropologists ethnologists sociologists historians devoting themselves study family names clan article includes study several important topics -

Curriculum Vitae Ya-Ting T. Liao, Ph.D

Curriculum Vitae Ya-Ting T. Liao, Ph.D. CONTACT INFORMATION Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Case Western Reserve University 10900 Euclid Avenue, Glennan 479 Cleveland, Ohio 44106 Phone: 216-368-0048 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio Doctor of Philosophy, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, June 2011 • Thesis: “Three-dimensional model of solid ignition and ignition limit by a non-uniformly distributed radiant heat source” Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio Master of Science, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, August 2007 • Thesis: “Ignition and flame growth in concurrent forced flow over thick solids” • Award: Case Prime Fellowship, Case School of Engineering, Case Western Reserve University, 2005 National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Bachelor of Science, Mechanical Engineering, June 2004 Bachelor of Science, Physics, June 2004 EXPERIENCE Assistant Professor, Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, May 2015 to present • Research interests: solid pyrolysis, ignition, flame spread, material flammability, microgravity combustion, wildland fire, battery fire, enclosure fire, two-phase flow. • Glennan Fellowships Award, 2019 Thermo-Fluids Specialist, Multi-Physics Simulation Group FMC Technologies, Houston, Texas, May 2014 to March 2015 • Evaluated flow conditions and thermal performance of various kinds of subsea equipment during pipeline start-up, production, and shut-down. • Analyzed production fluid hydration formation time, Joule-Thomson effect in chocks, erosion rate inside pipelines, etc. • Supported internal/external clients. • Developed proprietary custom CFD software. CFD Engineer Yoya SciTech LLC, Cleveland, Ohio, January 2013 to December 2013 • Contracted for FMC Technologies. • Built multi-phase flow analysis software from scratch, with a Fortran CFD backend and Java GUI front-end.