Translation of Names and Comparison of Addressing Between Chinese and English from the Intercultural Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

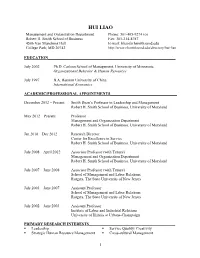

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (O) Robert H

HUI LIAO Management and Organization Department Phone: 301-405-9274 (o) Robert H. Smith School of Business Fax: 301-214-8787 4506 Van Munching Hall E-mail: [email protected] College Park, MD 20742 http://www.rhsmith.umd.edu/directory/hui-liao EDUCATION_________________________________________________________________ July 2002 Ph.D. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota Organizational Behavior & Human Resources July 1997 B.A. Renmin University of China International Economics ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS__________________________________ December 2012 – Present Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland May 2012 – Present Professor Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland Jan 2010 – Dec 2012 Research Director Center for Excellence in Service Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2008 – April 2012 Associate Professor (with Tenure) Management and Organization Department Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland July 2007 – June 2008 Associate Professor (with Tenure) School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2003 – June 2007 Assistant Professor School of Management and Labor Relations Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey July 2002 – June 2003 Assistant Professor Institute of Labor and Industrial Relations University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PRIMARY RESEARCH INTERESTS____________________________________________ . Leadership . Service Quality/ Creativity . Strategic Human Resource Management . Cross-cultural Management 1 MAJOR SCHOLARLY AWARDS AND HONORS__________________________________ . 2012, Named an endowed professorship – Smith Dean’s Professor in Leadership and Management, Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland . 2012, Cummings Scholarly Achievement Award, OB Division, Academy of Management . -

Presentation

Preprint, 18th Conference on Numerical Weather Prediction American Meteorological Society, Park City, UT 1B.4 Analysis and Prediction of 8 May 2003 Oklahoma City Tornadic Thunderstorm and Embedded Tornado using ARPS with Assimilation of WSR-88D Radar Data Ming Hu1 and Ming Xue1,2* 1Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma 2School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma Kalman filter (EnKF) data assimilation, (Snyder 1. Introduction * and Zhang 2003; Wicker and Dowell 2004; Zhang et al. 2004; Tong and Xue 2005; Xue et al. 2006). As a powerful tool in meteorological research Although both 4DVAR and EnKF demonstrate and weather forecast, numerical simulation was great advantages in the radar data assimilation for used by many researchers in the past three storms, their high computational cost hampers decays to study the tornado and tornadogenesis. their application in the operation and with a large Trough 2-dimensional axisymemetric vortex domain. models and three-dimensional asymmetric vortex Another efficient way to assimilate multiple models (Rotunno 1984; Lewellen 1993; Lewellen radar volume scans is to employ intermittent et al. 2000), the dynamics of the vortex flow near assimilation cycles with fast analysis methods, the tornado core were studied under the such as using ARPS (Advanced Regional environment that guarantees tornado formation. Prediction System, Xue et al. 1995; 2000; 2001) To include the effect of tornado parent three dimensional variational (3DVAR) analysis mesocyclone and study the tornado formation and (Gao et al. 2002; 2004) to analyze the radar evolution, different fully three-dimensional models radial velocity data and other conventional data with moist physics and turbulence were used by and the ARPS complex cloud analysis to retrieve Grasso and Cotton (Grasso and Cotton 1995) and thermodynamic and microphysical fields from the Wicker and Wilhelmson (Wicker and Wilhelmson reflectivity according to semi-empirical rules 1995) to simulate tornado vortices produced in a (Zhang et al. -

Curriculum Vitae

CHAO GUO School of Social Policy and Practice Phone: (215) 898-5532 University of Pennsylvania Fax: (215) 573-2099 3701 Locust Walk Email: [email protected] Philadelphia, PA 19104-6214 Web: http://www.drchaoguo.net Education Ph.D., Public Administration, 2003 University of Southern California (Advisor: Terry L. Cooper) B.A., International Relations, 1993 Renmin University of China Recent Awards and Honors Best Conference Paper Award, Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Washington DC, 2016. Nonresident Senior Fellow, Fox Leadership International, University of Pennsylvania, 2015- present. Penn Fellow, University of Pennsylvania, 2015-present. Best Conference Paper Award, Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action, Denver, 2014. Finalist, Indiana Public Service Award, Indiana Chapter of the American Society for Public Administration, 2013. Top Research Paper Award, Public Relations Division, National Communication Association, Orlando, 2012. Recognition for greatly contributing to the career development of the University of Georgia (UGA) students. Given by the UGA Career Center. 2011. The Inaugural IDEA Award (Research Promise), Entrepreneurship Division, Academy of Management, Anaheim, 2008. David Stevenson Faculty Fellowship, Nonprofit Academic Centers Council, 2005-2006. Kellogg Scholar Award, Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action’s 32nd Annual Conference, Denver, 2003. Chao Guo Emerging Scholar Award, Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action’s 30th Annual Conference, Miami, 2001. Dean’s Merit Scholarship, School of Policy, Planning and Development, University of Southern California, 1995-2000. Outstanding Leadership Award, Office of International Services, University of Southern California, 1997. Academic Experience Associate Professor, School of Social Policy and Practice, University of Pennsylvania, 2013- present. -

A Study of Modality System in Chinese-English Legal Translation from the Perspective of SFG*

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 497-503, March 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.4.3.497-503 A Study of Modality System in Chinese-English Legal Translation from the Perspective of SFG* Zhangjun Lian School of Foreign Languages, Southwest University, Chongqing, China Ting Jiang School of Foreign Languages, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China Abstract—As a special genre, legislative discourse reflects the power of a state through the usage of unusual forms of expressions in choosing words and making sentences. Based on the theory of modality in Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG) and the theory of legislative language in forensic linguistics, this study is designed to analyze the modality system in English translation of Chinese legislative discourses in its attempt to explore its translation problems. Through qualitative and quantitative analyses with the aid of Parallel Corpus of China’s Legal Documents, it is found that there are three prominent anomic features in English translation of modality system in Chinese legislative discourses. These features reveal that translators of Chinese legislative discourse pursue language diversity at the cost of accuracy and authority of the law. A summary of some tactics and suggestions are also presented to deal with the translation of modality system in Chinese legislative discourses from Chinese into English. Index Terms— modality system, Chinese legislative discourses, Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG) I. INTRODUCTION Translation of Chinese laws and regulations is an important component of international exchange of Chinese legal culture. Based on the theoretical ideas of functional linguistics, translation is not only a pure interlingual conversion activity, but, more important, “a communicative process which takes place within a social context” (Hatim & Mason, 2002, p. -

Third Edition 中文听说读写

Integrated Chinese Level 1 Part 1 Textbook Simplified Characters Third Edition 中文听说读写 THIS IS A SAMPLE COPY FOR PREVIEW AND EVALUATION, AND IS NOT TO BE REPRODUCED OR SOLD. © 2009 Cheng & Tsui Company. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-88727-644-6 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-88727-638-5 (paperback) To purchase a copy of this book, please visit www.cheng-tsui.com. To request an exam copy of this book, please write [email protected]. Cheng & Tsui Company www.cheng-tsui.com Tel: 617-988-2400 Fax: 617-426-3669 LESSON 1 Greetings 第一课 问好 Dì yī kè Wèn hǎo SAMPLE LEARNING OBJECTIVES In this lesson, you will learn to use Chinese to • Exchange basic greetings; • Request a person’s last name and full name and provide your own; • Determine whether someone is a teacher or a student; • Ascertain someone’s nationality. RELATE AND GET READY In your own culture/community— 1. How do people greet each other when meeting for the fi rst time? 2. Do people say their given name or family name fi rst? 3. How do acquaintances or close friends address each other? 20 Integrated Chinese • Level 1 Part 1 • Textbook Dialogue I: Exchanging Greetings SAMPLELANGUAGE NOTES 你好! 你好!(Nǐ hǎo!) is a common form of greeting. 你好! It can be used to address strangers upon fi rst introduction or between old acquaintances. To 请问,你贵姓? respond, simply repeat the same greeting. 请问 (qǐng wèn) is a polite formula to be used 1 2 我姓 李。你呢 ? to get someone’s attention before asking a question or making an inquiry, similar to “excuse me, may I 我姓王。李小姐 , please ask…” in English. -

I Want to Be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition

Volume 6 Issue 1 2020 “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan [email protected] ISSN: 2057-1720 doi: 10.2218/ls.v6i1.2020.4398 This paper is available at: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lifespansstyles Hosted by The University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan The years leading up to the political handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China surfaced issues regarding national identification and intergroup relations. These issues manifested in Hong Kong films of the time in the form of film characters’ language ideologies. An analysis of six films reveals three themes: (1) the assumption of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and Putonghua, (2) the importance of English towards one’s Hong Kong identity, and (3) the expectation that Mainland immigrants use Cantonese as their primary language of communication in Hong Kong. The recurrence of these findings indicates their prevalence amongst native Hongkongers, even in a post-handover context. 1 Introduction The handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 marked the end of 155 years of British colonial rule. Within this socio-political landscape came questions of identification and intergroup relations, both amongst native Hongkongers and Mainland Chinese (Tong et al. 1999, Brewer 1999). These manifest in the attitudes and ideologies that native Hongkongers have towards the three most widely used languages in Hong Kong: Cantonese, English, and Putonghua (a standard variety of Mandarin promoted in Mainland China by the Government). -

General Pre-‐Departure Information

LIU GLOBAL • CHINA CENTER 4.14.16 GENERAL PRE-DEPARTURE INFORMATION VISA 1. If you have not applied for your Chinese visa, please do so ASAP. 2. Please refer to Important Visa Information document to check the visa application details. BUY AIR TICKETS LIU Global students are encouraged to book air tickets well in advance of their departure. We recommend that students traveling to China for the first time fly directly into Hangzhou Xiaoshan International Airport (HGH) on a domestic or international flight, although this may not be the least expensive options. Students with sufficient international travel experience may also fly directly to the Shanghai Pudong International Airport (PVG) or Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport (SHA) and arrange other transportation to Hangzhou by train or bus. For students arriving in China independently, there are several cities in China that have international connections with the United States and European countries, including Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Hangzhou Xiaoshan International Airport (HGH) has international connections to Hong Kong, Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Bangkok and Singapore. ITEMS TO BRING AND NOT TO BRING REQUESTED SUGGESTED DO NOT ² Passport ü Prescription Medications × Illicit narcotic and ² Valid Chinese Visa (All ü Laptop psychotropic drugs students are required to ü Feminine Hygiene Products × Pornographic material of arrange a student visa ü Non-Prescription Drugs you typically any kind prior to departure for use to control cold, flu, cough, × Religious or political China) allergies, and indigestion, such as material ² A valid Health Insurance aspirin and ibuprofen, Tums, × Cold cuts or fresh fruit Policy Robitussin ü Research books ü Dictionaries ü Winter coat CONTACT INFO 1. -

Tales of a Medieval Cairene Harem: Domestic Life in Al-Biqa≠‘|'S Autobiographical Chronicle

LI GUO UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME Tales of a Medieval Cairene Harem: Domestic Life in al-Biqa≠‘|'s Autobiographical Chronicle Among the findings of recent scholarship on medieval Arabic autobiography1 is a reaffirmation, or redefinition, of the long-held notion that the realm of "private" life was "never the central focus of pre-modern Arabic autobiographical texts."2 To address this paradoxical contradiction between the business of "self- representation" and the obvious lack of "private" material in such texts, four sets of recurring features have been identified to help in uncovering the "modes" the medieval Arabic authors used to construct their individual identities: portrayals of childhood failures, portrayals of emotion through the description of action, dream narratives as reflections of moments of authorial anxiety, and poetry as a discourse of emotion.3 Other related areas, such as domestic life, gender, and sexuality, are largely left out. The "autobiographical anxiety," after all, has perhaps more to do with the authors' motivations to pen elaborate portrayals, in various literary conventions, of themselves as guardians of religious learning and respected community members (and in some cases, to settle scores with their enemies and rivals) than self-indulgence and exhibitionist "individuating." In this regard, a good example is perhaps the universally acclaimed autobiographical travelogue, the Rih˝lah of Ibn Bat¸t¸u≠t¸ah (d. 770/1368), who married and divorced over a period of thirty years of globetrotting more than twenty women and fathered, and eventually abandoned, some seventy children. However, little, if any, information is provided © Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. -

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: a Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012

Social Mobility in China, 1645-2012: A Surname Study Yu (Max) Hao and Gregory Clark, University of California, Davis [email protected], [email protected] 11/6/2012 The dragon begets dragon, the phoenix begets phoenix, and the son of the rat digs holes in the ground (traditional saying). This paper estimates the rate of intergenerational social mobility in Late Imperial, Republican and Communist China by examining the changing social status of originally elite surnames over time. It finds much lower rates of mobility in all eras than previous studies have suggested, though there is some increase in mobility in the Republican and Communist eras. But even in the Communist era social mobility rates are much lower than are conventionally estimated for China, Scandinavia, the UK or USA. These findings are consistent with the hypotheses of Campbell and Lee (2011) of the importance of kin networks in the intergenerational transmission of status. But we argue more likely it reflects mainly a systematic tendency of standard mobility studies to overestimate rates of social mobility. This paper estimates intergenerational social mobility rates in China across three eras: the Late Imperial Era, 1644-1911, the Republican Era, 1912-49 and the Communist Era, 1949-2012. Was the economic stagnation of the late Qing era associated with low intergenerational mobility rates? Did the short lived Republic achieve greater social mobility after the demise of the centuries long Imperial exam system, and the creation of modern Westernized education? The exam system was abolished in 1905, just before the advent of the Republic. Exam titles brought high status, but taking the traditional exams required huge investment in a form of “human capital” that was unsuitable to modern growth (Yuchtman 2010). -

The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System*

T’OUNG PAO 130 T’oung PaoXin 101-1-3 Wen (2015) 130-167 www.brill.com/tpao The Road to Literary Culture: Revisiting the Jurchen Language Examination System* Xin Wen (Harvard University) Abstract This essay contextualizes the unique institution of the Jurchen language examination system in the creation of a new literary culture in the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). Unlike the civil examinations in Chinese, which rested on a well-established classical canon, the Jurchen language examinations developed in close connection with the establishment of a Jurchen school system and the formation of a literary canon in the Jurchen language and scripts. In addition to being an official selection mechanism, the Jurchen examinations were more importantly part of a literary endeavor toward a cultural ideal. Through complementing transmitted Chinese sources with epigraphic sources in Jurchen, this essay questions the conventional view of this institution as a “Jurchenization” measure, and proposes that what the Jurchen emperors and officials envisioned was a road leading not to Jurchenization, but to a distinctively hybrid literary culture. Résumé Cet article replace l’institution unique des examens en langue Jurchen dans le contexte de la création d’une nouvelle culture littéraire sous la dynastie des Jin (1115–1234). Contrairement aux examens civils en chinois, qui s’appuyaient sur un canon classique bien établi, les examens en Jurchen se sont développés en rapport étroit avec la mise en place d’un système d’écoles Jurchen et avec la formation d’un canon littéraire en langue et en écriture Jurchen. En plus de servir à la sélection des fonctionnaires, et de façon plus importante, les examens en Jurchen s’inscrivaient * This article originated from Professor Peter Bol’s seminar at Harvard University. -

中国人的姓名 王海敏 Wang Hai Min

中国人的姓名 王海敏 Wang Hai min last name first name Haimin Wang 王海敏 Chinese People’s Names Two parts Last name First name 姚明 Yao Ming Last First name name Jackie Chan 成龙 cheng long Last First name name Bruce Lee 李小龙 li xiao long Last First name name The surname has roughly several origins as follows: 1. the creatures worshipped in remote antiquity . 龙long, 马ma, 牛niu, 羊yang, 2. ancient states’ names 赵zhao, 宋song, 秦qin, 吴wu, 周zhou 韩han,郑zheng, 陈chen 3. an ancient official titles 司马sima, 司徒situ 4. the profession. 陶tao,钱qian, 张zhang 5. the location and scene in residential places 江jiang,柳 liu 6.the rank or title of nobility 王wang,李li • Most are one-character surnames, but some are compound surname made up of two of more characters. • 3500Chinese surnames • 100 commonly used surnames • The three most common are 张zhang, 王wang and 李li What does my name mean? first name strong beautiful lively courageous pure gentle intelligent 1.A person has an infant name and an official one. 2.In the past,the given names were arranged in the order of the seniority in the family hierarchy. 3.It’s the Chinese people’s wish to give their children a name which sounds good and meaningful. Project:Search on-Line www.Mandarinintools.com/chinesename.html Find Chinese Names for yourself, your brother, sisters, mom and dad, or even your grandparents. Find meanings of these names. ----What is your name? 你叫什么名字? ni jiao shen me ming zi? ------ 我叫王海敏 wo jiao Wang Hai min ------ What is your last name? 你姓什么? ni xing shen me? (你贵姓?)ni gui xing? ------ 我姓 王,王海敏。 wo xing wang, Wang Hai min ----- What is your nationality? 你是哪国人? ni shi na guo ren? ----- I am chinese/American 我是中国人/美国人 Wo shi zhong guo ren/mei guo ren 百家 姓 bai jia xing 赵(zhào) 钱(qián) 孙(sūn) 李(lǐ) 周(zhōu) 吴(wú) 郑(zhèng) 王(wán 冯(féng) 陈(chén) 褚(chǔ) 卫(wèi) 蒋(jiǎng) 沈(shěn) 韩(hán) 杨(yáng) 朱(zhū) 秦(qín) 尤(yóu) 许(xǔ) 何(hé) 吕(lǚ) 施(shī) 张(zhāng). -

The Case of Wang Wei (Ca

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 5-6_full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Sufeng Xu _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Courtesan as Famous Scholar _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Courtesan as Famous Scholar T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 587-630 www.brill.com/tpao 587 The Courtesan as Famous Scholar: The Case of Wang Wei (ca. 1598-ca. 1647) Sufeng Xu University of Ottawa Recent scholarship has paid special attention to late Ming courtesans as a social and cultural phenomenon. Scholars have rediscovered the many roles that courtesans played and recognized their significance in the creation of a unique cultural atmosphere in the late Ming literati world.1 However, there has been a tendency to situate the flourishing of late Ming courtesan culture within the mainstream Confucian tradition, assuming that “the late Ming courtesan” continued to be “integral to the operation of the civil-service examination, the process that re- produced the empire’s political and cultural elites,” as was the case in earlier dynasties, such as the Tang.2 This assumption has suggested a division between the world of the Chinese courtesan whose primary clientele continued to be constituted by scholar-officials until the eight- eenth century and that of her Japanese counterpart whose rise in the mid- seventeenth century was due to the decline of elitist samurai- 1) For important studies on late Ming high courtesan culture, see Kang-i Sun Chang, The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism (New Haven: Yale Univ.